Rexroth's Old Chinatown

Historical Essay

by Kenneth Rexroth, written in September 1973, reposted from the collected columns of Rexroth at the Bureau of Public Secrets

It’s amazing how much San Francisco has changed since I came here in 1927. Legendary old San Francisco is usually thought of as, to quote that immortal epic The Girl with the Blue Velvet Band, “that city of wealth, beauty and fashion, dear old Frisco where I first saw the light” — the wild and glamorous town of the years before the Fire (Earthquake). But it’s extraordinary how legendary and far away the San Francisco of pre-Depression days has become.

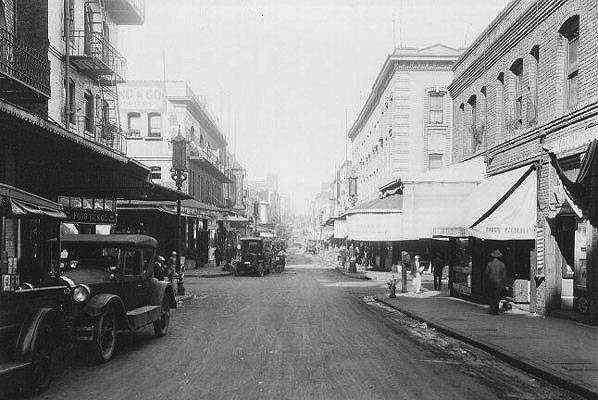

Grant Avenue at Jackson Street, 1926.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

To start, as the tourist does, with Chinatown: a majority of the men still wore black sateen suits and little caps and smoked tobacco in the iron and bamboo pipes that all the honkies thought contained opium. Real hip white people called it a yen hock, which in fact is corrupt Cantonese for the needle on which opium is roasted. There were lots of women with Golden Lilies or Golden Lotuses, bound dwarfed feet, teetering along Grant Avenue where some of the signs still said Dupont Street. Big black limousines full of singsong girls shepherded by a solemn fat mama came and went from Chinese banquets, at which all sorts of depraved capers were imagined to go on. Walking along Grant Avenue of an evening you were never out of the sound of rattling mahjong tiles. The stores all had small paned windows, closed at night with wooden or sheet-iron shutters. I remember the first modern storefront in Chinatown, a restaurant on Washington Street below Grant, long since vanished. Crowds of curious Chinese watched the place being rebuilt, utterly fascinated. The next, the first on Grant Avenue, was the Fong Fong Bakery and Ice Cream Parlor, still there. In the little basement and alley restaurants with their menus only in Chinese, chalked on a blackboard, you could get a good meal for 25¢.

The Chinese community policed itself. It had the highest tuberculosis rate, but the lowest delinquency and crime rate in the City. One thing the tourists were always looking for were Chinese girls, but the days of hundreds of little cribs with the girls calling out “Two bittie looky! Four bittie feely! Six bittie doeey!” were long gone. There were still brothels on Bush Street but the girls were Caucasian and the prices were high. The famous Gentleman’s Agreement had given over the policing of Chinatown to the Chinese community and all interracial “vice” was very effectively banned, except for Chinese lottery tickets which were sold by the thousands every morning all over the City.

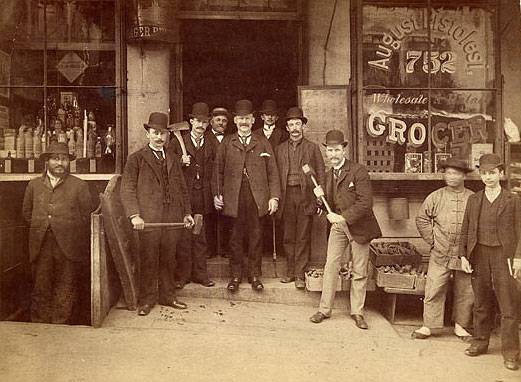

Chinatown Squad of the SF Police Dept. posing with sledgehammers and axes in frontof August Pistolesi's grocery store at 752 Washington Street, 1895.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

There was a Chinatown Detail of Caucasian plainclothes police, a bunch of Keystone Cops, whose duties seemed to consist of loitering together on street corners, spitting on the sidewalk, and collecting the clout. The best restaurants were Hang Far Low, Tao Yeuan, and the Moon Café of happy memory. An acupuncturist used to operate on the street, and it was common to see somebody sitting quietly against the wall, stuck full of needles. One of the most fascinating characters was a little old man with a sublimely happy face surrounded with, for a Chinese, quite bushy white hair and beard. He was a trapper in the marshes near the head of the Bay, and each week he brought in a raccoon or a possum or a wildcat or a gray fox, two animals at a time, rolled alive in chicken wire and suspended from a yoke over his shoulder. These he sold to customers, who had them killed and skinned (the skin cured and saved for a health vest — for this purpose the wildcat was considered the best). The meat, and especially the organs, and most especially the bile duct and testicles, was cooked and eaten — guaranteed to put lead in your pencil, even if you didn’t have anybody to write to. Usually he also had a sack of snakes, including defanged rattlers, which he sold for the same purposes. In his old, old age he was arrested by the police of the California Fish and Game Commission, and died in prison.

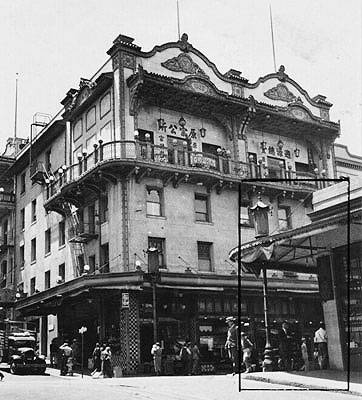

Grant and Clay 1935

Photo: courtesy San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

There were three, sometimes four, Chinese theaters, where the entire repertoire of Chinese opera could be seen night after night, and after ten o’clock admission was only 25¢. Since Chinese plays never really get going until halfway through, it was possible to spend every night watching one of the world’s greatest theatrical traditions for little more than the price of a package of cigarettes. Those were the great days of the Cantonese theater, before the old traditional costumes gave way to gaudy things covered with huge glittering sequins, and when Chinese actors were still trained from childbirth not only in flawlessly perfect acting technique but in the most fantastic acrobatics, and the actresses in equally agile dancing. It was also before the years when the Chinese theater became overwhelmed with male impersonators, women in heroes’ roles.

Today such theatrical performances would be prohibitively expensive. There is no longer a full-time Chinese theater in the City (shockingly enough, there isn’t one in Taipei either), and even the heavily subsidized festival performances nowadays cannot compare with what you got for 25¢ admission a generation ago.

With the change in taste, Chinese theatrical costumes and the traditional clothing of the Chinese upper classes were thrown on the second-hand market and “Mandarin coats” and suchlike could be bought for a few dollars from high-piled tables in the two largest Chinese art goods stores. Chinatown was full of bargains of this sort, and it was hard to figure out how the merchandise, food, clothing, hardware, art objects, could be delivered to the customer at such prices. Along the line, nobody could have made more than a few pennies on each transaction, from the Canton pawn shop to the final clubwoman from Des Moines.

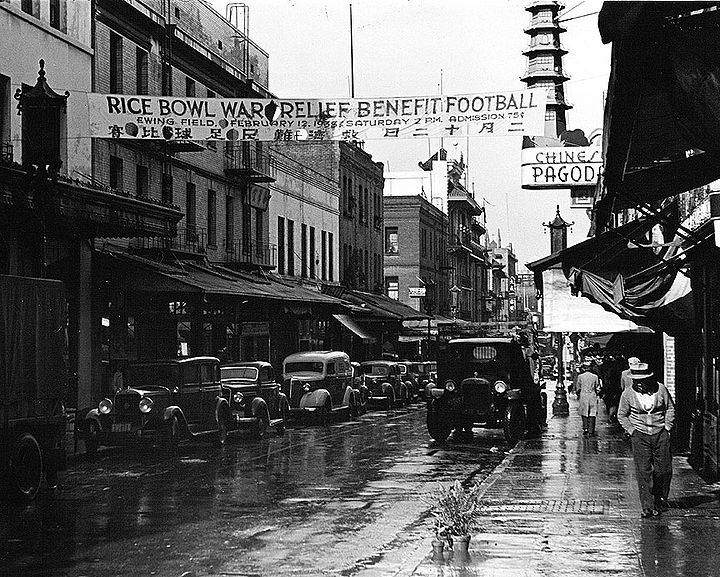

Chinatown street with banner advertising a February 12, 1938 benefit at Ewing Field.

Photo: Courtesy of Jimmie Shein

There was another side of the coin. When I came to San Francisco I expected to meet all sorts of people with whom I could discuss the great poets, philosophers and painters of China. But classical Chinese culture was a closed book to all but a few old men who could not communicate with a Caucasian, and a Chinese woman doctor and her brother. When C.H. Kwock arrived from Hong Kong and Honolulu to work on the Chinese World, with an enthusiastic knowledge and love of the classical culture, he was the first person of his kind in the community.

Concomitantly, the hidden, deep-rooted prejudice against the Chinese, which prevailed in all circles of the white community, dumbfounded me. I had been friends during his stay in America with the great Chinese poet Wen I-to, later assassinated by the Kuo Min Tang, and had many other Chinese friends. I discovered that even among radical bohemians here, if I said “At the University of Chicago where I went, an oriental student is a preferred date,” it was as though I had made a mess on the floor.