Progressive Municipal Reform 1890-1900

Historical Essay

by William Issel and Robert Cherny

Sailors Union of the Pacific headquarters on the Embarcadero c. 1890s.

Photo: Bancroft Library

By the early 1890s journalists routinely pointed out that "the heart of the Democracy" throbbed in "the laboring district" South of Market Street. More careful observers would have distinguished between the "Regular" Buckley supporters and the backers of the “Reform Democracy:” Though led by a millionaire banker of Irish Catholic parentage and a corporate lawyer who preached an ideology of honesty and efficiency in government, the reform faction used its own techniques of "honest graft" to depose Buckley. Party politics during the early 1890s thus contained an unstable mixture: "military-style" election time adventure (especially attractive to the action-seeking working class) existed alongside appeals for businesslike government (highly tempting to the stable working class).

Although the reform faction that forced Buckley from his leadership position in the Democratic party used "packed" grand juries and crooked nominating conventions as freely as "the Boss" had done, its goals were quite different. The reformers aimed at the eventual creation of a stable, dependable party organization capable of routinely capturing office with out having to depend on the unruly, adventuresome, election-day foot soldiers from the South of Market who had been an important part of Buckley's electoral army. Like the regime of "Honest John" Kelly in New York City, whose purge of the more rowdy, undisciplined, "dangerous" elements from the Democratic party has led Martin Shefter to describe him as the man who made "democracy safe for capitalism," the junta of Gavin McNab in San Francisco brought together stable, home-owning, upwardly mobile ethnic working-class voters and the city's wealthy younger mercantile and financial capitalists.(1)

These business leaders, typified by banker James Phelan and by the San Francisco Merchants' Association (1894), acted from the conviction that the city's future economic prosperity required promotion of business by means of municipal fiscal encouragement, as well as protection from both confiscatory taxation and capricious expenditures.(2) They regarded city government as too important to be left to the undisciplined outcomes of urban political conflict. The businessmen-reformers characteristically fitted their economic development interests with a "legal-rational" philosophy of municipal government that illustrated their increasing unease with the "traditional" point of view that had dominated nineteenth-century urban politics. The traditional approach-as practiced most effectively by Buckley emphasized personal relationships and deemphasized both institutional structure and specialized training. The legal-rational approach, by contrast, laid stress on the importance of both structure and method. Charter revision in the 1890s provides a vivid illustration of such concern with the structure of urban government. The new politics of "businesslike" municipal government favored methods avowedly scientific, based on careful research designed to discover the "best" (usually meaning most efficient) way of accomplishing a task. The legal-rational approach to politics usually emphasized the importance of expertise and sought to recruit specially trained analysts.

The Charter Reform Movements

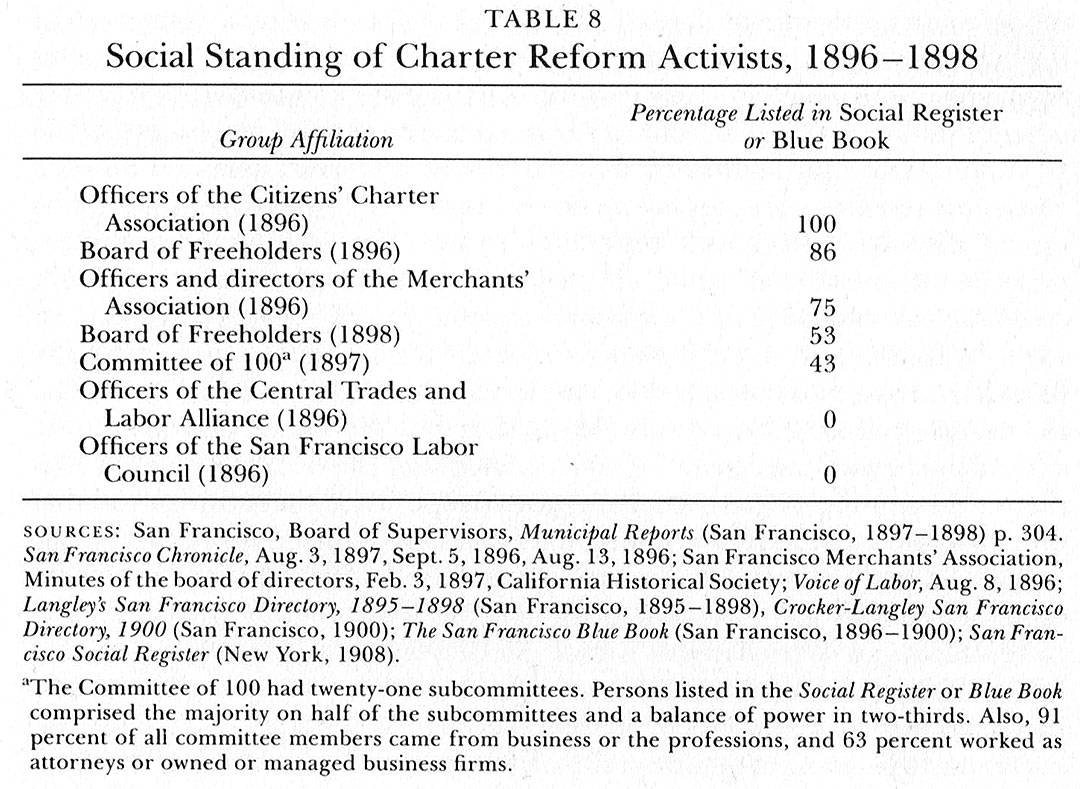

Reformers made unsuccessful attempts in 1880, 1883, and 1887 to modernize the city charter, but their successful campaign of the 1890s began at the end of the depression winter of 1893-1894 and coincided with the first anniversary of the Labor Council of San Francisco. In April, some fifty members of the city's business elite formed the Merchants' Association, which was dedicated to the application of business principles of management and nonpartisanship to municipal government. (See Table 8 for the social composition of participants in charter reform politics.) Soon the association succeeded in obtaining the city contract for street sweeping, and its campaign to improve sales by beautifying sidewalks prompted journalists to hail its work as "the sign of a municipal awakening.”(3)

In October, with unemployed workers flocking to the city in anticipation of another hungry winter, the association assumed the leadership of a charter reform campaign. During their meeting that month, the members of the association heard the president of the Pacific Coast Technical Society applaud "the impulse among businessmen and commercial bodies to cure the loose methods and lack of business principles in the expenditure of their money for benefits, privileges and enjoyments for which they pay but which they do not receive.” A charter grounded in the principles of business would improve the situation in San Francisco where, "as in so many of our large cities, the village system of dealing with some of the most vital problems bearing on domestic comforts and commercial prosperity has obtained too long.”(4)

The fifteen members of the Board of Freeholders elected in November agreed with the Merchants' Association version of municipal reform, and they too called for efficiency, an end to waste, strengthening the power of the mayor, and an appointed Board of Education. Even physician Jerome A. Anderson, elected on the Populist ticket, believed that the best way of "making somebody responsible" was to make the city "run like any other great corporation." At the same time, Anderson wanted municipal ownership of public utilities. He thereby expressed a seemingly contradictory, but frequently espoused, goal: favoring the corporate ideal for municipal decision making along with desiring popular control over the production of necessary municipal services.(5)

Shortly after the freeholder election, the California superintendent of schools announced the essentials of a program for school centralization that would guide discussions for the next four years. He held up the record of "reform" city superintendents in eastern cities as the model for the West, and he urged the creation of small nonpartisan school boards accountable to central city officials rather than neighborhood ward voters. A program of centralization appealed to the San Francisco Teachers' Club as well, but before advising the freeholders, the teachers consulted "prominent educators" and studied the "leading Eastern cities." They suggested a five-member nonpartisan board appointed from the career teachers with at least five years of experience in the city's schools. They also called for strict separation of the business and teaching functions of the school system.(6)

That same day, a Chronicle editorial on "good city government" argued for the application of "modern theory" to San Francisco: "Curtail the number of elective officers,”for the resultant system of "power coupled with the strictest responsibility offers the best possible solution for the evils of bad and inefficient government.” For the Chronicle, good government meant efficient government, and efficient government meant a municipal order modeled on corporate outlines: "The Board of Freeholders is composed of businessmen, and they should apply to the creation of a charter the rules of business with which they are familiar. All the good and respectable people of San Francisco will favor a charter framed on the general plan suggested.”(7)

Walter Macarthur, editor of the Coast Seamen's Journal, assumed no such automatic harmony among businessmen, business interests, and the interests of the city's "good and respectable people." He had hinted at quite a different conception of ideal urban government in his remarks to those assembled at a meeting of the reform-oriented Civic Federation earlier that week. With financier I. J. Truman (one of the freeholders) as president, the federation passed resolutions demanding an end to election fraud and called for the beginning of home rule. Macarthur put the Labor Council on the side of the federation's goals, but he warned that the council "believes that the real beginning of this movement goes deeper than these things and that the workingmen themselves must have the opportunity to work for fair wages and get justice in the courts." Macarthur's qualified support for the Civic Federation matched that of M. M. McGlynn, editor of the Voice of Labor, the organ of the Labor Council. McGlynn also urged home rule, and he especially opposed fraudulent use of public money for private gain and corporate profit. From McGlynn's perspective "as a trades unionist, it was particularly pleasing to see the eminently respectable gentlemen of the cloth or the law advocate the very same measures that ten years ago they called the trades unionists anarchists for advocating."(8)

If Macarthur and McGlynn drew connections between class and politics in their remarks on the Civic Federation, so did its president, I. J. Truman, in his remarks on the need for civil service measures in the new charter. "The City Hall,” he said, "has many men who would be a success as brick layers, blacksmiths, farm hands, etc., but who are out of place as clerks and accountants." From Truman's perspective, working-class officials could not be expected to possess the wisdom necessary for decision making in municipal government. Nor could working-class voters be expected to exercise intelligence in selecting members for the school board. The mayor should appoint board members, for "it is more likely he will appoint parties fitted by education and moral standing in the community.”(9)

When the Civic Federation adopted its permanent constitution, organized labor was absent from the roster of participating groups, and the bylaws included a clause requiring a three-fourths majority for the admission of new members. At the same time, the ties between the Civic Federation and the Board of Freeholders were strengthened when two more of the freeholders became officers of the federation. The remarks of free holder W. F. Gibson—that although a large board of supervisors "is more in harmony with the democratic form of government,” the "sentiment of the city is at present opposed to that idea"—may well have been based on his perception of the Civic Federation as constituting the legitimate representative of "the sentiment of the city."(10)

The close connections among the Merchants' Association, the Civic Federation, and the Board of Freeholders helped yield a charter strong on centralization, civil service, and corporate principles in general. The charter contained no provisions for municipal ownership of public utilities, and, except for its inference that the working class lacked expertise and should be kept far from power, it promised no solution to the problem of private abuse of the public trust. ·

The 1896 Charter Fight

The Voice of Labor immediately criticized these weaknesses as it opened an intensive campaign to defeat the charter in the election of 1896. Centralization would "wholly fail to stem the tide of municipal corruption,” and "what we stand for and insist upon is our right, as a city, to make our own laws, by popular vote, upon such subjects as properly belong to city government." One month later, at a citywide convention of labor reformers and trade unionists called by the Labor Council, the audience heard a variety of speakers condemn the document. The Merchants' Association, on the other hand, gathered the questionnaires it had sent to the members of the city's business associations and other "clubs of social, commercial or political importance" and proclaimed that "public opinion is overwhelming" on behalf of civil service, business methods, and the new charter. The Citizens' Charter Association introduced the term progressive into San Francisco's political vocabulary in 1896 when it described the kind of voter that "may be counted on as a friend of the new Charter":

Those who wish for a City Government conducted on business principles, and free from reference to national or state politics; ... merchants who want to have this city made the equal of other large cities of the United States in public improvement, cleanliness of streets, attractiveness to visitors, as well as in commerce and enterprise; ... [those] whose interests require that the industrial activity of our municipality should be encouraged, public buildings erected, private real estate improved and increased in value ... and in general, all the progressive elements among the voters of San Francisco.(11)

For a year, while the newspapers published copies of the charter and speculated about its chances, the alignment remained stable. Merchants' Association, Civic Federation, and freeholders stood on one side; organized labor lined up on the other. Then in late June 1896, the chancellor of the archdiocese of San Francisco, Peter Yorke, added the influence of the Monitor, the official paper of the archdiocese, to the side of labor. The Central Trades and Labor Alliance had charged that the charter included "provisions directly against the rights and interests of labor" and "does not provide for the initiative and referendum, proportional representation, or any other means whatever of insuring government by the people instead of by bosses.” Yorke now charged that the freeholders had ignored the evolutionary nature of municipal government in their "attempt to turn out governments for cities as men turn out sausages." The Voice of Labor had argued that the charter "displayed the determination to curtail and minimize the rewards of labor" and that anyone who supported it "must regard property above flesh and blood.” The Monitor now scored the charter as "supremely vicious" because "the trail of the APA [the nativist American Protective Association] is visible across it.” Singling out the provision for hiring teachers as his major target, Yorke suggested that its requirement that public school teachers be public school graduates "means that if a parent wishes to educate his child where he believes best, he is to be punished by having that child debarred from teaching in the public schools."(12)

As James Walsh has recently pointed out, Yorke's defense of Catholicism against the APA had mainly symbolic importance and resulted in little more than the silencing of several strident orators. The nativist organization never possessed social, political, or economic power in San Francisco, and even the possibility shrinks given the fact that active Catholics outnumbered church going Protestants by about five to one. Although the APA may have posed little threat to San Francisco Catholics, the mobilization of Catholics against the charter created doubts about its success, for the Irish constituted the most highly politicized ethnic group in the city.(13)

At about the time the Merchants’ Association asked the San Francisco Election Commission to place the charter at the top of the ballot, Yorke intensified his opposition. Then he accused the Merchants' Association of nativism and demanded that they explain "why they are doing the dirty work of the APA."(14)

The Labor Council met one week after this attack and, perhaps stimulated by the priest's opposition, elected a slate of officers even more opposed to the charter than the previous leadership. They then voted to decline the invitation to the charter convention called by the Merchants' Association, and they decided instead to prepare a pamphlet against the charter for distribution to the city electorate.(15)

The Merchants' Association in the meantime asked James Phelan to preside over a Citizens' Charter Association of San Francisco that would meet every two weeks until the election. The choice of Phelan, a member of the association and a wealthy Catholic of Irish stock, may have been calculated to placate potential Catholic opposition. The charge by former mayor and state senator Frank McCoppin that "religious sentiments of the people are being played upon for the purpose of making votes against the charter" may have been intended to discredit the validity of Yorke. But any support gained by the choice of Phelan probably was offset when the merchants chose Horace Davis for vice-president. Davis had led a union-busting merchants' protective association in 1892, and organized labor warmly disliked him for his comment in 1894 that since much of the power of the unions had been destroyed, "capital will now flow into our city like water.”(16)

The charter convention met for the first time on August 12, with Frederick Dohrmann, head of the Merchants' Association, as temporary chair man. Before introducing Phelan, Dohrmann explained one part of the strategy that he hoped would secure the victory of the charter. The association would use the already existing neighborhood organizations that represented "the best element and the best class of our citizens" to build a network of activists throughout the city. The other part of the campaign plan was discussed at a meeting of the directors of the Merchants' Association. After director Maurice Rothchild reported on his visit to Peter Yorke and explained the priest's opposition, the directors decided to appropriate $1,000 to support the campaign and to send a delegation to "visit the Chronicle, Report and such other newspapers as they may select to secure their cooperation for the charter."(17)

Except for an acceleration in the pace of the battle, the general character of the conflict continued into September according to the pattern set by the end of August. The Chronicle published several exposes of municipal corruption consistent with the charter supporters' goals. The secretary of the Merchants' Association published the official pamphlet urging voters to regard the charter as modeled on "the most Progressive cities of the United States" and to see that its public school clause was actually a device to ensure that "education must be practical."(18)

By late September, several events introduced new complications into the situation. Public school teachers opposed to the charter adopted a newly militant position and held several meetings to protest the school clause. Apparently, teachers stood about equally divided on the charter, but the opposition (probably Catholic in large part) charged that it represented "a vicious attempt to do away with the tenure of office of teachers." At about the same time, the city's political party system lumbered into action in anticipation of the election. Regular and reform factions vied for legitimacy within both major parties, and their mayoralty nominations revealed the strength of the ethnic divisions rending the city's politics.(19)

The regular Democrats, successors to the now greatly weakened "Blind Boss" Buckley, billed themselves as the "Anti-Charter Democrats" and appealed to voters with language already made familiar by the Labor Council and Peter Yorke. Challenging the Buckley Democrats, but still within the councils of the party, the reform faction nominated Phelan for the mayoralty but carefully avoided making a direct endorsement of the charter. On the Republican side, the business and good-government faction nominated a popular city merchant, Charles Laumeister. Like Phelan, once he became a candidate, Laumeister avoided taking a public stand on the charter, but he did stress the need for a city government responsive to the needs of trade and commercial interests. Opposed to the reform Republicans stood the regulars under the guidance of John Spreckels, whose alleged links to the APA provided additional fuel for the already intense ethnic dimensions of the election. The Spreckels faction's nominee, Charles S. Taylor, tagged by the Monitor as "the nominee of the APA convention,” also avoided mention of the charter.(20)

The parties could no more contain the ethnic divisiveness that generated these alignments than they could the class conflict that accompanied them. The chairman of the meeting for the charter on October 22 found himself confronted with "hisses, howls, hoots and cat calls" that lasted ten minutes when a speaker mentioned the name of the APA mayoralty candidate. Walter Macarthur, representing the Labor Council at the same meeting, argued that "there are but three classes in the city—the working class, the begging class, and the thieving class. Of these only the first has a right to be represented." Macarthur "denied that the charter would bring home rule" and saw it instead as a device for imposing what he called "class rule.”(21)

The Labor Council made a similar argument in its pamphlet that Macarthur had helped to write. While "the confessed purpose of the proposed new system of government is centralization,” it was also the case that "the assumption which underlies the Charter is that the people at large cannot be trusted to elect an honest government." Voters should see the charter as "a system retrogressive in every particular, representative of class despotism and absolutely unalterable." Urging reform in methods of accountability rather than a change in the principle of representation, the Labor Council argued that "elective government must be retained, and if possible enlarged, as the only safeguard of popular government." The pamphlet provided a thorough critique of the charter, but the council concluded with an affirmation of its interest in honest municipal government and home rule and called for a new, more representative, charter convention.(22)

San Francisco voters defeated the charter some two weeks after Macarthur attacked it as a vehicle for class rule, even though they chose Phelan for the mayoralty (voters gave about two votes to Phelan for every one that went for the charter). Phelan had been swept into the mayor's office on a platform of responsible municipal administration modeled after corporate management. Prosperity after 1897, Phelan's skillful use of patronage (for example, he cultivated Patrick McCarthy, head of the Carpenters' Union, and eventually appointed him to the Civil Service Commission), and factional fights within the labor movement complicated the political situation.

The Campaign for the 1898 Charter

Peter Yorke immediately supported the Labor Council's demand for a more representative "charter of compromise." "This city," he argued, "is not made up entirely of merchants and does not exist for the well-to-do alone. The laboring man, the tradesman, the artisan, have as much at stake here as the merchant prince. Therefore any association which is working for the good of the city must open wide its ranks and gather in all these classes."(23)

The Merchants' Association quickly reassembled its ranks and planned a new campaign, explaining that "we do not want a class charter, but it must be for the people and for all the people." One of the directors admitted that "we have begun at the wrong end and tried to make a charter for the people without first finding out what they wanted."(24)

By the time Phelan presented his inaugural address on January 4, 1897, the Merchants' Association had begun a campaign to centralize the neighborhood improvement clubs into a weapon for the charter. Phelan, having kept silent about the charter during his campaign, assumed leadership in his capacity as mayor, regretted that "the city does not possess a more scientific and satisfactory charter," and called for a Committee of 100 to draft another document. Phelan also brought the question of school reform into the center of attention and argued for "the necessity of practical trade and technical education. . . . This has been a source of prosperity to numerous cities, for by improving the technical skill of the artisans and mechanics, the product of their labor finds sale in the markets of the world." He then asked the grand jury to investigate "extravagance" in school spending, thereby putting into motion a year-long campaign of exposé.(25)

Three days later, Phelan walked into the office of the Merchants' Association and asked its secretary “to prepare a list of names from which the Committee of 100 might be selected." The Merchants' Association then worked closely with Phelan throughout the first half of 1897. By the time the Committee of 100 met for the first time in July, the association had also begun to put the public schools in the forefront of the campaign.(26)

As the gradual improvement of business conditions in 1897-1898 brought the promise of renewed prosperity, organized labor demanded that its interests be represented in the Committee of 100. Having hoped for a committee of elected members, labor found that "one man has selected from among his personal friends and political supporters such men as he thought would give the convention the appearance of having a representative character." Trade unions "represent at least one-third of the population . . . and should have had at least one-third of the delegates, whom they should have been permitted to select." Instead, "four men alone were selected from their ranks, and those were taken without the authority of the unions." The procedure was not "likely to create confidence in the brains of the city's workers.”(27)

Similar concerns emerged when the subcommittee on education met with teachers and principals to draft the school clause of the charter. The subcommittee had invited the principal of each school, as well as one elected teacher from each school, but a number of teachers complained of their reluctance to vote for a school clause. They pointed out that "they had been chosen rather to be present and report back proceedings than to vote on behalf of those who had chosen them." The vote proceeded, with about half of the teachers abstaining, the resolutions for centralization passed, and the dissenters returned to their colleagues to report the fait accompli.(28)

The Committee of 100 also exercised considerable skill in dismissing the point of view of dissident members of the small minority representing labor. Only the insistence of the one socialist member saved the suggestions of the Trades and Labor Alliance from being buried in committee without a reading. They gained a hearing, but nothing more.(29)

The socialist member remained isolated from the other labor members as well as from the business and professional majority. The most vocal trade unionists—Walter Macarthur of the Coast Seamen’s Journal and Patrick McCarthy of the Carpenters' Union—stayed at opposite sides of the political spectrum from the start. One reporter went so far as to describe McCarthy as "more conservative than any of the millionaires.” The same observer noted that while the minority had no power, "the sincerity of the radicals is appreciated and humored by the conservatives." "Indeed," he continued, "these theorists have never had such a thoughtful audience to work upon and the capitalists are quite as responsive and interested as the men who have neither property nor possessions to hazard by experiments in State control and communism."(30)

This vocal but ineffectual minority provided the support for the proposal for a board of eighteen supervisors elected by ward, a plan, noted the Voice of Labor, that "would have carried with it all that element in the community which favors democratic organization of municipalities." The proposal actually chosen by the committee, described by one newspaper as "the American plan of concentrating executive functions in the hand of the mayor," had "its strongest adherents among the property holders and the conservative elements of the convention.”(31)

By the time the Committee of 100 finished its draft for a charter, the majority had decided against its original plan of presenting the voters alternatives on the most contentious issues such as mayoralty power, control over public utilities, public school governance, and direct democracy measures such as the initiative and referendum. The Merchants' Association continued to advertise the committee as "thoroughly representative," despite the continued cries of labor to the contrary, and the neighborhood improvement associations in the newer areas of the city had formed a citywide organization. This new San Francisco Improvement Association then declared its intention to follow the example of the Merchants' Association in its campaign for a charter.(32)

The late December election of the Board of Freeholders, which would officially present a charter to the electorate for approval, rekindled the factional fighting that had split the city's party system during the election of 1896. The Committee of 100 fielded a slate taken from its ranks (with McCarthy the only member from the labor contingent) that earned the prompt endorsement of the reform elements of both major parties. The regular Democrats joined with the Populists in a "fusion ticket," and the Socialist Labor party presented its own nominees.(33)

One week before the freeholder election, the chairman of the Election Commission, William Broderick, asked Phelan to explain "why it was that, in making up the Committee of 100, only six were selected from six of the leading Democratic districts and three large Democratic districts were entirely overlooked. I have an interest in the Democratic Party and I would like to know why the Democracy south of Market Street was not considered worthy of more representation."

The making of a charter is not a matter of geography, replied the Mayor. It certainly is a matter of judgement, responded Broderick, and it certainly would have been better to have had the Democratic party represented. The committeemen were selected with reference to their occupation rather than their location, said Phelan. I am of the opinion, said Broderick, that it was constructed on other lines, and the list was fixed up by you and a few others in a back room.(34)

Broderick made a valid argument when he observed that the assembly districts with the largest representation on the committee were the wealthiest areas of the city. He could also have pointed out that the working class districts of the city held only eighteen seats. The middle- and upper-class districts held the balance of the positions in the committee.(35)

The Catholic press contained no criticisms of the ethnic makeup of the committee, and in the issue of the Monitor published two days before the election, Peter Yorke announced that the slates seemed nonpartisan and, therefore, satisfactory. The APA issue had receded in importance, and the priest's opposition did not reappear.(36)

About one-third of the registered voters came to the polls on December 26, 1897, and they chose by a small margin the freeholder slate nominated by the Committee of 100. Highest turnout occurred in the assembly districts that had been best represented in the committee whereas the lowest turnout came from the working-class districts South of Market and in the Mission.(37)

Phelan, the Merchants' Association, and the freeholders lost no time in renewing their campaign. Three days after the election, Andrew S. Draper, former Cleveland superintendent of schools and a leading educational reformer, described the ingredients of "a desirable school system" at a meeting called by the mayor. Draper reviewed the usual litany of "formidable difficulties" facing city school systems and presented the standard list of remedies by means of centralization. The elements of Draper's centralization program informed the final school clause of the charter. Perhaps the freeholders had, like the Chronicle, "watched school proceedings with amazement and disgust" during some six months of charge and counter charge between grand jury and school board members over nepotism and personnel problems. Nonetheless, they offset their proposal for an appointed school board with a concession to critics in the form of an elected superintendent.(38)

If centralization succeeded as the basis for the public school clause, it also succeeded in the section on the Board of Supervisors. At the final meeting of the freeholders, with Phelan attending, a vote was taken to consider an earlier proposal that the charter should provide an eighteen member board with two from each of nine districts elected by district. This proposal was defeated, and the freeholders decided to recommend what was described as a "radical change" to a Board of Supervisors nominated and elected at large.(39)

With only a month remaining before the special May 26 election for the charter, the Labor Council met to consider its merits. McCarthy, the only labor member of the Board of Freeholders, took the offensive and argued that the working-class interests had been fully considered. Another speaker agreed, saying that "every responsible suggestion emanating from labor leaders had been carefully considered and granted, and valid and satisfactory reasons had been given for not granting other demands from the same source." Other members argued otherwise, that "the charter was framed in the interest of capital and that the rights of labor had been entirely ignored." This division among Labor Council activists continued onto the pages of the Voice of Labor. Its editorial writer informed readers that although the charter could have contained a stronger initiative and referendum clause, it possessed good features as well as bad, and he would be "satisfied to abide by [the voter's] judgement." At the same time, the paper continued to print attacks on the charter.(40)

The Monitor refused to take sides on the charter, for Yorke now saw it "purely as a political instrument" and "entirely free of bigotry and injustice." If Yorke proved unwilling to raise the ethnic issues, Phelan, speaking to a rally of workers in the South of Market two days before the election, showed no such reluctance. Here, millionaire Phelan shared the platform with carpenter McCarthy, the one the son of Irish parents, the other an Irish immigrant. Phelan announced that "the charter would give the city what the people of Ireland have been fighting for and what the boys in blue are now going to the front to win—home rule." McCarthy explained that the charter's provision for two dollars per day and an eight-hour day for city laborers made it "a charter that would benefit the common people. Isn't that enough for the working people?" he asked.(41)

In an editorial in the Coast Seamen's Journal the same day, Macarthur answered that it remained far from being enough.

This is, in effect, a proposition that labor should be willing to vote for any old system of government as long as that part of it that works for the City Hall gets eight hours and $2 per day. If the new Charter will run any risk at all by this insinuation that the working man of San Francisco is a sheer ass its chances of adoption are pretty slim.(42)

Macarthur's differences from McCarthy stemmed from deep-seated disparities in their perceptions of the needs of the labor movement. Working class voters may also have noticed another difference: Macarthur was a Scotsman, and Scandinavians constituted 40 percent of his union (the Sailors' Union), but the Irish made up the largest group both in the city and in the labor move ment.(43)

Several events in April and May could have influenced the judgment of voters as much as newspaper arguments and ethnic loyalties. Augustus Widber, city treasurer, absconded with over $100,000 in public money, only to be caught and convicted. Charter supporters lost no time pointing to ways the charter, with its provisions for efficient professional city management, could help ensure against such criminal behavior. Then the Merchants' Association stepped up its campaign after Phelan warned them against allowing a false sense of security to lull them into defeat. The charter supporters also decided to begin "addressing the workmen at the mills and foundaries" and distributed 22,500 copies of the May issue of the Merchants' Association Monthly Review devoted especially to the charter.(44)

When the polls closed on May 26, some 26,969 of the 73,410 registered voters had cast their ballots on the charter, giving it a victory of 14,389 to 12,025. According to Macarthur in the Coast Seamen's Journal and a journalist in a San Francisco newspaper, the Report, the low turnout occurred because the polls closed two hours before sunset in violation of both state law and public announcements by the freeholders. Macarthur argued that the election commissioners thus tricked many workers into what "practically amounted to the disfranchisement of large numbers of voters." Whatever the case, the turnout for the special election (37 percent) had dropped by four percent age points from the turnout on the charter of 1896 during the general election when the charter vote had lagged far behind the vote for mayor and national candidates, during a period in which the mean turnout was 84 percent.(45)

The Report accurately observed that "the strength of the adverse vote was from the districts of small residences." In fact, only six of the city's eighteen assembly districts mustered a majority against the charter, and four of them (waterfront districts 28, 32, 44, and 45) housed the seamen and dock workers most likely to have been swayed by Macarthur and the Coast Seamen's Journal. The other two opposition districts (31 and 43) yielded such close votes that a handful of switchers could have shifted them into the other column, but they too ranked high in working-class populations. These districts teemed with unskilled and transient workers who lived where small homes, boardinghouses, and hotels huddled together intermixed with commercial and industrial firms and where only small proportions of the population owned their homes. The greatest support for the charter came from what were still called the suburban residential areas in the western and southwestern parts of the city where most residents owned substantial homes, from the residential area just west of Nob Hill, and from the only two working-class districts where appreciable numbers owned their homes.(46)

The greatest support derived from the areas of the well-to-do, including those filling up with what Robert Wiebe has called "the new middle class" and the districts of the skilled workers with steady employment. With the vote so close in most of the eighteen assembly districts, we can learn more by grouping them according to ethnic criteria and then noting the characteristics of those falling above and below the citywide vote of 55 percent for the charter. The newer and well-to-do districts that gave the charter substantial support ranked highest in old-stock and ethnic residents. The working-class districts that registered a lower yes vote than the city as a whole-including the eight districts that would soon provide the Union Labor party with its base of support-also happened to hold the lowest proportions of old-stock population in the city.

The reform charter of 1898 thus emerged as the product of a campaign by organized business led by the Merchants' Association rather than the result of a personal crusade by Mayor Phelan. Phelan did play an important role in the campaign, but it began when, as a member of the Merchants' Association, he supported the charter in his capacity as a private citizen. Organized labor played a crucial role in the battle for the charter, even though it displayed considerably less unanimity on the desirability of the reform than did business. The two groups together, displaying varying degrees of conflict and coalition, generated a political process that was also continually beset with overtones of ethnic consciousness.(48)

The participants themselves described the issues in language charged with class consciousness. Dismayed because "labor had been absolutely without representation" during the drafting of the charter and unimpressed by the fact that "a pretense was made at giving labor a seat," the editor of the Coast Seamen's Journal wrote that "the whole proceedings, from inception up to the present moment, have been controlled by one influence, i.e. Business." The Monthly Review, mouthpiece of the Merchants' Association, expressed "pardonable pride" in its ability to “justly claim to have inaugurated the movement that gave birth to the new Charter." The legal framework for the governing of San Francisco would now be "based upon the platform first enunciated by the Merchants' Association."(49)

Class consciousness and class conflict definitely shaped the course of the charter campaign, but they did so to the accompaniment of ethnic tensions. Solidarity among labor against the proposed charter helped ensure its defeat in 1896, but so did the determined opposition by Yorke because of its alleged dangers to the interests of Catholics. Divisions between workers over the proposed charter helped condition its victory in 1898, but so did the decision by the Catholic press that the new measure contained "no provisions which will operate against any citizen or class of citizens because of their faith."(50)

The new charter pleased the Merchants' Association and Mayor Phelan because it strengthened the powers of the city's chief executive: the mayor now had undivided authority to appoint and remove members of city boards and commissions; he could make charges against elected officials and suspend them while they awaited trial; he could veto ordinances of the Board of Supervisors, and the votes of fourteen of the enlarged eighteen-member board were necessary to override a veto. The provisions for at-large election of supervisors and for civil service pleased the business leaders more than the clauses permitting the city to utilize the initiative and referendum, establish publicly owned utilities, and initiate minimum-wage and maximum hour provisions for city employees. The Merchants' Association and Phelan accepted the latter, more populist, measures as a necessary cost of successful implementation of the structural reforms of the executive and legislative branches of municipal government. Martin Schiesl has recently described the nationwide movement for reform of municipal government, and his characterization fits San Francisco as well:

If they were to be successful their organizations had to be as efficient as the machine and ... designs to reorganize municipal government had to be complemented by practical schemes to gain and keep political power. Such conditions produced the search for controls which would centralize authority in the executive branch of local government.(51)

Notes

1. Quotations at the head of the chapter are from the Monitor, Nov. 7, 1896 (Yorke) and the Examiner, Aug. 25, 1911 (Rolph). For New York City, see Martin Shefter, "The Emergence of the Political Machine: An Alternative View” in Theoretical Perspectives on Urban Politics," ed. Willis Hawley et al. (Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1976), pp. 14-44.

2. Terrence McDonald has made a comprehensive statistical study of municipal government expenditure for the 1860-1910 period and concludes that during "the reform mayoralties of the 1890s, expenditure increased more annually than during the era of machine domination ... the 'machines' were more fiscally conservative and the reformers more expansionary:' He argues that the case of San Francisco suggests that although the reformers campaigned for economy and against the extravagance of the machine, in fact the machine had been too penurious. What was at stake, was not just how government should be structured, but what it should do, not just politics, but policy, and in the new political economy the power of politics was to be used to expand public expenditure and indebtedness in order to encourage local economic development. (McDonald, "Urban Development;' pp. 188-189, 204-205)

3. Monthly Review (San Francisco), Sept. 1896; Evening Post, Aug. 21, 1894; see also Young, San Francisco, 2:713.

4. Chronicle, Oct. 16, 19, 1894, Nov. 17, 1894.

5. Ibid., Nov. 17, 1894. Self-made millionaire Adolph Sutro, elected on the Populist ticket and mayor from Jan. 1895 to Jan. 1897, similarly supported a municipal government modeled on business methods as well as popular accountability. See Chronicle, Jan. 13, 1895, and his speech as he left the mayor's office in the Chronicle, Jan. 5, 1897.

6. Chronicle, Dec. 29, 1894, Jan. 12, 1895.

7. Chronicle, Jan. 11, 19, 1895.

8. For the Civic Federation, see the Chronicle and the San Francisco Call, Jan. 13-Feb. 26, 1895; Chronicle, Jan. 13, 27, 1895.

9. Chronicle, Jan. 20, 1895.

10. Chronicle, Jan. 19, 20, 1895.

11. Voice of Labor (San Francisco), Feb. 2, 1895, March 2, 1895; Call, March 13, 19, 1895; Chronicle, June 25, 1895,July 17, 1895; Gustav Gutsch, A Comparison of the Consolidation Act with the New Charter (San Francisco, 1896), quoted in McDonald, "Urban Development;' p. 203.

12. Call, Feb. 17, 1896; Monitor (San Francisco), June 27, 1896; Voice of Labor, May 2, 1896. Yorke had earlier criticized alleged charges by the American Protective Association (APA) that "60 percent of the teachers in San Francisco are Roman Catholics" as a "groundless untruth"; see Monitor, Jan. 11, 1896. On the details of Yorke's battle against the APA, see Brusher's biography, Consecrated Thunderbolt, ch. 2.

13. James P. Walsh, Ethnic Militancy: An Irish Catholic Prototype (San Francisco, 1972), pp. 15-19, tables on pp. 16-17; see also James P. Walsh, "Abe Ruef Was No Boss: Machine Politics, Reform, and San Francisco;' California Historical Quarterly 51 (Spring 1972):13-14.

14. San Francisco Merchants' Association, Minutes of the board of directors, July 9, 1896, California Historical Society, San Francisco, hereafter cited as M.A. Minutes; Monitor, July 25, 1896.

15. Voice of Labor, Aug. 8, 15, 1896.

16. M.A. Minutes, Aug. 6, 1896; Frank McCoppin, Address on the New Charter, pamphlet dated Aug. 11, 1896, p. 11, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley; the statement had appeared in Voice of Labor, March 2, 1895.

17. Chronicle, Aug. 13, 20, 1896; M.A. Minutes, Aug. 20, 1896.

18. The Chronicle began its muckraking campaign on Sept. 13, 1896, with head lines announcing "Disease Lurks in the Corridors" of city hall. See also stories on Sept. 14, 15, 16, 1896. The pamphlet, prepared by J. Richard Freud, was entitled New Charter Catechism, Plain Questions and Honest Answers (San Francisco, 1896), copy in California Historical Society, San Francisco. Freud urged voters to "Take up the Chronicle and see the pictures" in speeches in favor of the charter; see Chronicle, Sept. 16, 1896.

19. Chronicle, Sept. 20, 25, 1896; Call and Examiner, Sept. 25, 1896. Albert Lyser, principal of the John Swett School, made the claim about divisions among teachers in an interview with a journalist (the name of the newspaper and the date have been clipped) in vol. 1 of the Phelan Scrapbooks, Phelan Papers, Bancroft Library.

20. For the day-to-day details see the following: Chronicle, Sept. 19, 22, 29, 1896, Oct. 2, 1896; Monitor, Oct. 3, 1896; Call, Oct. 8, 1896; Post, Oct. 10, 1896; Chronicle, Oct. 28, 29, 1896; Nation, Oct. 24, 1896; Examiner, Oct. 28, 1896; Chronicle, Oct. 31, 1896.

21. Chronicle, Oct. 23, 1896. See also Monitor and Star (San Francisco), Oct. 3, 1896, and Socialist, n.d., in vol. 1, Phelan Scrapbooks, Bancroft Library.

22. San Francisco Labor Council, The New Charter: Why It Should Be Defeated (San Francisco, 1896), pp. 3, 5, 6, 11, copy in California Historical Society, San Francisco.

23. Yorke's recommendations appeared in Monitor, Nov. 7, 1896.

24. Chronicle, Nov. 14, 1896; see also M.A. Minutes, Nov. 5, 1896.

25. Chronicle, Dec. 9, 1896, Jan. 5, 1897; Bulletin, Jan. 6, 1897. For details on the school controversies, see Chronicle, Feb. 1, 1897, March 14, 1897, April 23, 30, 1897, May 13, 1897, June 14, 1897, July 24, 1897.

26. M.A. Minutes, Jan. 7, 21, 1897, Feb. 8, 25, 1897; Examiner, Feb. 24, 1897; Monthly Review, Jan.-March 1897; Chronicle, Jan. 22, 1897.

27. Voice of Labor, Aug. 7, 1897; see also the Aug. 14 and Sept. 4 issues. In keeping with the Merchants' Association strategy of making the charter campaign more representative, Phelan appointed both Walter Macarthur and Patrick McCarthy to the Committee of 100. At the same time, the committee remained very much an upper- and middle-class group because only five were blue-collar workers besides the two labor union officials. Occupations of 104 of the 115 members of the committee can be traced in city directories. Forty owned or managed business firms; another thirty-one were independent professionals; fourteen were salaried professionals; nine worked in white-collar jobs. There were two state and one federal government employees. A list of the committee appeared in the Chronicle, Aug. 3, 1897.

28. Chronicle, Aug. 18, 1897.

29. Chronicle, Sept. 10, 1897. Richard Freud, secretary to the Merchants' Association and the Committee of 100, later stated that the original committee reports had all been destroyed because, he wrote, "they differed frequently so much from their form after final adoption by the Committee"; letter from Richard Freud to J.C. Rowell (librarian of the University of California), dated March 13, 1899, bound with pamphlets on San Francisco charters, vol. 1, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

30. Wave (San Francisco), Oct. 16, 1897; see also Call, Oct. 21, 1897; Chronicle, Oct. 27, 1897; Coast Seamen's Journal (San Francisco), Nov. 17, 1897.

31. Voice of Labor, Sept. 25, 1897; Wave, Oct. 16, 1897; Call and Post, Oct. 21, 1897.

32. Chronicle, Sept. 29, 1897; Monthly Review, Nov. 1897; Chronicle, Nov. 25, 1897.

33. The details can be followed in Examiner, Oct. 21, 25, 1897; Call, Oct. 22, 23, 1897; Chronicle, Oct. 27, 28, 31, 1897, Nov. 3, 8-12, 18, 1897; Wave, Nov. 20, 1897; Chronicle, Nov. 28, 1897, Dec. 3, 1897; Town Talk, Dec. 13, 1897; Post, Dec. 16, 1897.

34. Chronicle, Dec. 18, 1897; a table listing the delegates by assembly district appeared in the article.

35. This and the later discussions of class, ethnicity, and voting rest upon data compiled from the following sources: California Blue Book, 1899 (Sacramento, 1899), maps of assembly districts; San Francisco, Municipal Reports (1897-1898, 1900-1901), pp. 375, 374; U.S. Census Office, Department of the Interior, Twelfth Census of the United States: 1900, 37 vols. (Washington, D.C., 1902), 1:738-739, 868, 876-877, 884-885, 892-893, 900-901, 904-905; 2:702, 754, Bulletin 66, p. 8; Averbach, "South of Market;' pp. 202-203, and note 38 on p. 220. See also Alexander Saxton, "San Francisco Labor and the Populist and Progressive Insurgencies," Pacific Historical Review 34 (Nov. 1965):421-438; and Michael P. Rogin and John L. Shover, Political Change in California: Critical Elections and Social Movements, 1890-1966 (West port, Conn., 1970), ch. 1. Old stock is used to describe native-born persons with native-born parents whereas ethnic refers to foreign-born persons and natives with at least one foreign parent.

36. Monitor, Dec. 25, 1897.

37. Chronicle, Dec. 28, 29, 1897; Coast Seamen's journal, March 2, 1898. See also sources in note 35.

38. Chronicle, Dec. 31, 1897, Feb. 18, 1898, March 2, 3, 22, 1898.

39. Chronicle, March 26, 1898.

40. Chronicle, April 25, 1898; Voice of Labor, May 14, 21, 1898. See also Coast Seamen's Journal, March 2, 1898; Star, May 14, 1898; and letter to the Chronicle, May 21, 1898.

41. Monitor, May 21, 1898; Examiner, May 25, 1898.

42. Coast Seamen's Journal, May 25, 1898.

43. Sources in note 35; and Cross, A History of the Labor Movement in California, pp. 330, 336-337.

44. Monthly Review, May 1898; Chronicle, April 25, 1898; Chronicle, May 6, 1898; Examiner, May 21, 1898; see Chronicle during April 1898 for the details on Augustus Widber.

45. Coast Seamen's journal, June 1, 1898; Report (San Francisco), May 27, 1898. Terrence McDonald calculated the mean voter turnout ("participation rate") in "Urban Development;' p. 164.

46. Ibid., and Report, May 27, 1898.

47. Wiebe, Search for Order, pp. 111-132. Note that whereas the Irish ethnics outnumbered the old-stock residents by about one-fourth, they owned more than twice the number of homes. See Twelfth Census of the United States: 1900, vol. 2, pt. 2, Table 115, p. 754.

48. The charter has traditionally been known as "the Phelan Charter:'

49. Coast Seamen's Journal, May 25, 1898; Monthly Review, June 1898.

50. Monitor, May 21, 1898.

51. Martin J. Schiesl, The Politics of Efficiency: Municipal Administration and Reform in America: 1880-1920 (Berkeley, 1977), p. 47.

Excerpted from San Francisco 1865-1932, Chapter 7 “Progressive Politics, 1893-1911”