Catholic San Francisco: A City of Contests

Historical Essay

by William Issel, 2013

This is the introduction to Issel's 2013 book, "Church and State in the City: Catholics and Politics in Twentieth-Century San Francisco"—scroll to bottom for links and information

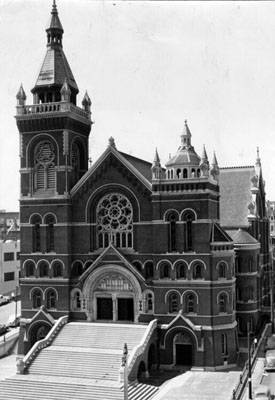

St. Mary's Cathedral on Van Ness, October 10, 1953

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

Many myths populate the conventional wisdom about American cities, but one of the most tenacious is the notion that San Francisco has always been the nation’s “Left Coast” city: a decidedly un-American carnival of secular humanism featuring warring tribes of radicals thumbing their noses at tradition and authority while onlookers adopt a devil-may-care tolerance for whomever turns up no matter what they do. The myth developed from a kernel of truth, the reality that from Gold Rush days, to the Dot Com Boom, to the Great Recession, San Francisco has attracted more than its share of rebels and bohemians whose adventures and escapades fit the mythic profile. But to imagine the San Francisco story as primarily a narrative of the libertine lifestyles and noisy antics of its more rebellious residents writ large is to lose sight of the city’s actual history: one that is both more complicated and closer to the American mainstream. Perhaps the most glaring omission in the construct of mythical San Francisco is its erasure of religion in the city’s history, including hard fought contests among faith-based religious reformers, libertarian- oriented capitalists, and secular socialists and communists that have marked the city’s public life.

The streets of twentieth-century San Francisco rang with the sound of these contests. Residents clashed over who should be included in the definition of “the public,” which members of the public should have a say in determining the priorities of life in the city, and how the common good, the public interest, should be defined and implemented. The city’s history has featured conservative Christians as well as irreligious radicals, laissez-faire capitalists as well as revolutionary socialists, white supremacists as well as racial liberals, not to mention those whose worldviews have defied simplistic labels. This latter group, for instance, includes the Roman Catholic nuns who were fierce critics of unfettered capitalism and fought for the rights of men and women in the workplace, while at the same time opposing feminism and birth control.

September 16, 1962: St. Mary's Cathedral at Van Ness and O'Farrell after a major fire destroyed the church.

Charles Cushman Collection: Indiana University Archives (P12690)

These contests have shaped the city’s twentieth-century history and contributed to its contemporary reputation as a place where participation in the political process for defining the common good is open to all residents, irrespective of class, ethnicity, color, creed, gender, sexual orientation, or disability. The purpose of this book is to reconsider San Francisco history, over nearly a century, while taking into account the role of Catholic faith-based activism. The book develops a two-part argument. First, San Francisco politics beginning in the 1890s was directly influenced by the deliberate attempts of the Catholic Church and devout Catholic men and women to influence the terms of debate about the common good and to shape public policy according to their faith- based values. Second, Catholics found themselves in conflict with laissez-faire capitalists, secular liberals, and anti-Catholic socialists and communists. These secular aspirants for political influence were just as determined as their religious rivals to shape the city’s public philosophy and its public policies. Despite their sometimes irreconcilable differences, laissez-faire capitalists, anticapitalist socialists and communists, and secular liberals envisioned the good society as one built on a foundation of individual rights and freedom of choice unencumbered by traditions of faith and clerical authority. This put them on a collision course with the church and with those politically active Catholics for whom God-given duties and obligations that individuals owed to one another should set limits to individual freedom and constrain the content of government policies in a city named for St. Francis.(1)

The contests that resulted from the competition among these rival constituencies were highly complex affairs; after all, the city housed others besides Catholics; Catholics did not think with one mind and behave as a political bloc; and religious faith did not always trump other sources of political thought and action among Catholics. The complexities only increased as the great events of the twentieth century impinged on the city, as its population increased in size and ethno-racial and cultural diversity, and as San Franciscans pursued their local political agendas in the context of national and international developments from the 1890s through the 1970s.(2) Like that of many American big cities in the twentieth century, especially major international port cities, San Francisco’s experience was marked above all by social diversity and by robust social movements and efforts at political reform. San Francisco was not—no city can be said to be—typical, but its economic role as a regional, national, and inter- national business center, its cultural role as a favored destination for migrants and immigrants, and its political role as a site for policy innovation all qualify it to be a significant, and distinctive, American study site.(3)

Archbishop Hannah celebrates St. Ignatius Diamond Jubilee, Oct. 24, 1930.

Photo: Bancroft Library

April 11,1941, Good Friday: Parishioners on the steps of St. Mary's.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

The roots of the long debate over defining the common good in San Francisco can be found in late-nineteenth-century contests between capital and labor, contests that also involved the Catholic Church and Catholic laypeople. A newly organized business front decided that business priorities were equivalent to the community interest and that capitalists were best equipped to shape the city’s future. These determined businessmen found themselves in a struggle with residents, many of them inspired by Catholic social theory, who were sympathetic to the claims of white working-class men for equity in the workplace and equality in the councils of government. From 1901 to the 1930s, despite an aggressive anti-union movement and robust hostility to socialism and anarchism, sympathy for the rights of white working-class men attracted support among a broad spectrum of community leaders and ordinary voters. However, few challenged white supremacy and the restricted gender roles that limited women to the domestic realm and to public roles associated with the health, education, and welfare of children. During the New Deal years, from 1933 to roughly 1941, the city’s culture and politics were invigorated by the reorientation of national discourse on behalf of expanded legal rights for organized labor and a by a distinctive local Catholic activism in public life. During World War II and into the Cold War years of the 1960s, a San Francisco version of mid-twentieth-century post–New Deal liberalism was challenged and then reformulated.

By the late 1960s, events and social changes external to the city and dramatic population changes during and after World War II, including a decline in the Catholic population of the city and changes in Catholicism itself, combined to cause a diminishing of the Catholic influence in San Francisco public life. A distinctive era of San Francisco history was coming to an end—an era that witnessed high degrees of influence of the Catholic notions that the common good derived from and must operate within the bounds of a God-given moral order, that individual rights must be balanced with duties and obligations given by Catholic tradition and values, and that local government should ensure that public policies are partial to and compatible with the specific content of Catholic Christian moral values. Since the 1960s, in San Francisco as in the United States generally, American political culture has increasingly privileged individual rights and freedom of choice unbounded by faith traditions, along with government neutrality vis-à-vis the values of particular religious moral traditions and the preferences of faith-based interest groups.(4)

"Red Mass" at Old St. Mary's, 1942.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

My purpose in this book is to present an analytical narrative of a series of contests over defining the public interest that demonstrate the central role of Catholicism, in complex relations with capitalism and with other social and institutional interests, in shaping the city’s public life. With regard to capitalism, San Francisco’s experience provides a dramatic illustration of the assertion that “it is impossible to exaggerate the role of business in developing great cities in America.”(5) Capitalists and business organizations found themselves embroiled in continual contests with the political left (including the Communist Party), organized labor, and the Catholic Church. Individual businessmen and business organizations were key players in the political processes used to initiate, implement, and monitor government policies; because city policy emerged from decisions of federal, state, and local governments, business concerned itself with all three levels of the political system. During the 1890s, businessmen created economic institutions designed to articulate their policy interests with efficiency and effectiveness. During the Progressive era and the 1920s, they used these new organizations, as well as political action groups and informal personal networks, to create governing coalitions and guide day-to-day urban decision making in ways that would accommodate business priorities. Businessmen and their organizations, often in league with members of the professions, were also key players in the origin and development of city planning.(6)

Never a monolithic political bloc, businessmen and their organizations bargained and competed with rivals while accommodating to internal differences. They rose above these divisions often enough to create an effective partnership with public officials. They served in elected and appointed positions themselves, and they worked as unofficial advisers to municipal officeholders; they played quasi-public roles in the routine operation of municipal agencies; they assisted research bureaus in contract work with city governments; and they assumed leadership roles in the establishment and management of municipal reform organizations and of large-scale urban infrastructure projects. Divisions among businessmen and their need to work in ways that required cooperation and compromise did not stand in the way of political success, and after World War II the political process became exceedingly complicated due to the rising power of organized labor. But no other community interest groups rivaled business in its ability to influence the debate about the public interest during the first half of the twentieth century, and business power remained formidable thereafter.

The power, privilege, and prestige of business did not mean that religion, specifically Catholicism, existed only on the margins. In San Francisco and nationwide, the relationship between religion and politics during the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century was significantly different from today. It is, of course, true that the concept of separation of church and state has been a central principle of American life since the Bill of Rights became part of the U.S. Constitution in 1791. Congress could not make Catholicism or any other religion the official faith of the country, nor could the federal government interfere with individual decisions about what faith to practice (or not). But before the 1940s, constitutional interpretation and federal policy allowed religious activists in cities and states considerable latitude when it came to bringing their faith-based values into the public sphere where government policy was debated.(7) The large number of Catholics in the San Francisco population, where they predominated in the blue-collar workforce and in business, government, and the professions, was a distinctive feature of San Francisco society. Not all Catholics practiced their religion, but a sizeable number of devout Catholics brought their faith-based convictions to bear in the public realm, as well as in their private lives, in ways that marked the city’s political culture as it developed after the 1890s. Catholic San Franciscans believed that it would be a hollow democracy indeed if antireligious and non-religious people were allowed to shape the public interest according to their beliefs, but Catholics were prohibited from doing so.(8)

Retelling the story of twentieth-century San Francisco with Catholicism at the center—in its relationships with business, labor, other interests groups, and city government—benefits the ongoing project among historians of urban America that aims to make the story of our big cities more evidence-based, more attentive to social diversity, and hence more sophisticated.(9) It has the added advantage of fostering serious consideration of one of the most important transnational challengers of both capitalism and Catholicism during the twentieth century: socialism, especially the Communist Party variant. Socialism played an important role in urban politics beginning in the 1880s. The Communist Party aspired to be a force in the nation’s cultural and political life starting in the 1920s, the decade in which the status and power of organized business reached a new high, and developed even further during the 1930s, when the reputation of business sank to a new low but the political power of the Catholic Church grew to its highest point thus far.(10) Contests to define the public interest took on a distinctive character in San Francisco because of the particular way that the local capitalist, Catholic, secular liberal, and socialist and communist struggles over power, privilege, and prestige were fought out, in the context of national and international events, from the 1890s to the end of the 1970s.

Church and State in the City begins in the 1890s and continues with chapters arranged generally in chronological order, but it is meant to be neither a decade-by-decade chronicle nor a comprehensive political history of the city. The purpose is to stimulate debate about the contours of San Francisco history and to contribute to rethinking the role of religion in American urban history, not to present a definitive account. The book, moreover, is frankly revisionist in challenging the notion that the history of urban politics and policy can be best understood as the unfolding of a coherent, progressive, secular modernization of urban political culture. Each chapter explores particular contests, selected because of their importance to city residents at specific moments in urban political development, the analysis of which provides insight into the complex and dynamic combination of change and continuity that marked the city’s history at every point of the twentieth century. The individual chapters have also been written so that readers will find each a coherent stand-alone historical analysis. Readers who wish a sense of the cumulative impact of the events included in the book will want to read it from beginning to end. Taken as a whole, the book offers a new interpretation, or reconsideration, of San Francisco’s history during the twentieth century.

Notes

1. Among the numerous works that have informed my thinking about American political culture, I have been especially influenced by Michael J. Sandel, Democracy’s Discontent: America in Search of a Public Philosophy (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1996); Michael J. Sandel, Liberalism and the Limits of Justice, 2d ed. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998); John Rawls, Political Liberalism, exp. ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005); John Rawls, The Law of Peoples (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999); Rogers M. Smith, Civic Ideals: Conflicting Visions of Citizenship in American History (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1997); Michael Walzer, Thinking Politically: Essays in Political Theory, 2d ed., ed. David Miller (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2007); Barry Bozeman, Public Values and Public Interest: Counterbalancing Economic Individualism (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2007); Louis Dupré, “The Common Good and the Open Society,” in Catholicism and Liberalism: Contributions to American Public Philosophy, ed. R. Bruce Douglass and David Hollenbach (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 172–195; Jean Bethke Elshtain, “Catholic Social Thought, the City, and Liberal America,” in Catholicism, Liberalism, and Communitarianism: The Catholic Intellectual Tradition and the Moral Foundations of Democracy, ed. Kenneth L. Grasso, Gerard V. Bradley, and Robert P. Hunt (Lanham, Md.: Rowman and Littlefield, 1995), 97–114; Gary D. Glenn and John Stack, “Is American Democracy Safe for Catholicism,” Review of Politics 62, no. 1 (Winter 2000), 5–29; Judith N. Shklar, American Citizenship: The Quest for Inclusion (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1991); Mary Ann Glendon, Rights Talk: The Impoverishment of Political Discourse (New York: Free Press, 1991); Akhil Reed Amar, The Bill of Rights: Creation and Reconstruction (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1998); Mark Hulliung, The Social Contract in America from the Revolution to the Present Age (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2007). For an impressive synthesis that places in the forefront theories about and the practice of “collective action for the public good” in the American city from the eighteenth century to the present, see John D. Fairfield, The Public and Its Possibilities: Triumphs and Tragedies in the American City (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2010). For a useful online forum with material regarding the concept of the public sphere, see Social Science Research Council, “Public Sphere Guide,” available online.

2. The excellent existing scholarship on San Francisco’s political culture is referenced throughout this book, but see esp. Richard Edward DeLeon, Left Coast City: Progressive Politics in San Francisco, 1975–1991 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1992); Robert W. Cherny, “Patterns of Toleration and Discrimination in San Francisco: The Civil War to World War I,” California History 73 (Summer 1994): 130–141; Philip J. Ethington, The Public City: The Political Construction of Urban Life in San Francisco, 1850–1900 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994); Glenna Matthews, “Forging a Cosmopolitan Civic Culture: The Regional Identity of San Francisco and Northern California,” in Many Wests: Place, Culture, and Regional Identity, ed. David M. Wrobel and Michael C. Steiner (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1997), 211–234; Gray Brechin, Imperial San Francisco: Urban Power, Earthly Ruin (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999); Barbara Berglund, Making San Francisco American: Cultural Frontiers in the Urban West, 1846–1906 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2007); Rebecca Solnit, Infinite City: A San Francisco Atlas (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010).

3. The importance of studying both the distinctive character of individual cities and

the dynamic nature of their histories is addressed in several excellent “state of the field”

essays by Robert O. Self, “City Lights: Urban History in the West,” in A Companion to the American West, ed. William Deverell (Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 2004), 412–441; Philip J.

Ethington and David P. Levitus, “Placing American Political Development: Cities,

Regions, and Regimes, 1789–2008,” in The City in American Political Development, ed.

Richardson Dilworth (New York: Routledge, 2009), 154–176; Clarence N. Stone, “Urban

Politics Then and Now,” in Power in the City: Clarence Stone and the Politics of Inequality,

ed. Marion Orr and Valerie C. Johnson (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2008),

267–316.

4. The literature on the history of constitutional interpretation and the politics of

policymaking in relation to the development of American political culture is extensive:

see, e.g., Sandel, Democracy’s Discontent.

5. Thomas C. Cochran and William Miller, The Age of Enterprise: A Social History of Industrial America, rev. ed. (New York: Harper and Row, 1961), 153. See also Sarah S. Elkind, How Local Politics Shape Federal Policy: Business, Power, and the Environment in Twentieth Century Los Angeles (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011).

6. For existing accounts that examine the influence of business, see Jeffrey Haydu, Citizen Employers: Business Communities and Labor in Cincinnati and San Francisco, 1879–1916 (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2008); Brechin, Imperial San Francisco; John H. Mollenkopf, The Contested City (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1983); Chester Hartman, City for Sale: The Transformation of San Francisco, rev. ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002).

7. As Charles Lippy writes, “The First Amendment aside, American religious life and American political life were never divorced from each other, but intertwined”: Charles H. Lippy, Pluralism Comes of Age: American Religious Culture in the Twentieth Century (Armonk, N.Y.: M. E. Sharpe, 2000), 124. Among the best of a recent outpouring of books on this topic are Donald L. Drakeman, Church, State, and Original Intent (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010); John Witte Jr. and Joel A. Nichols, Religion and the American Constitutional Experiment, 3d ed. (Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 2011); Paul Horwitz, The Agnostic Age: Law, Religion, and the Constitution (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011). See also John T. Noonan Jr., The Lustre of Our Country: The American Experience of Religious Freedom (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998); Christopher L. Eisgruber and Lawrence G. Sager, Religious Freedom and the Constitution (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2007); Steven K. Green, The Second Disestablishment: Church and State in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010).

8. Exceptions to the general neglect of Catholicism in San Francisco history include Jeffrey M. Burns, ed., Catholic San Francisco: Sesquicentennial Essays (Menlo Park, Calif.: Archives of the Archdiocese of San Francisco, 2005); Richard Gribble, Catholicism and the San Francisco Labor Movement, 1896–1921 (San Francisco: Mellen Research University Press, 1993); William Issel, “For Both Cross and Flag”: Catholic Action, Anti-Catholicism, and National Security Politics in World War II San Francisco (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2010).

9. See Kathleen Neils Conzen, “The Place of Religion in Urban and Community Studies,” Religion and American Culture 6 (Summer 1996): 108–114; Philip Goff, “Religion and the American West,” A Companion to the American West, ed. William Deverell (Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 2004), 286–303; Paula Kane, “Review Essay: American Catholic Studies at a Crossroads,” Religion and American Culture 16 (Summer 2006), 263–271.

10. Robert W. Cherny is at work on a history of the Communist Party in California: see Robert W. Cherny, “Prelude to the Popular Front: The Communist Party in California, 1931–35,” American Communist History 1 (June 2002), 11, 19–20; Robert W. Cherny, “The Communist Party in California, 1935–1940: From the Political Margins to the Mainstream and Back,” American Communist History 9 (April 2010), 3–33.

From pages 1-6, the Introduction to Church and State in the City: Catholics and Politics in Twentieth-Century San Francisco by William Issel. Used by permission of Temple University Press. © 2013 by Temple University. All Rights Reserved.