Louise Boyd: The Dame Who Tamed The Arctic

Historical Essay

By Reigh Robitaille

Part of the Wonder Women of the Bay Area series by I Spy Tours

Louise Boyd during the search for Amundson's lost party in the Arctic.

Photo: Adventure-Journal.com

Waves slammed into the sides of the massive ship. Its sturdy hull rose with each tide, before moaning back into the water with a nauseating seesaw sway. Inside, the crew carried on, charting the next course for their route. In the buffet room, waiters paused to steady their trays of champagne glasses, the bubbles dancing in a tizzy. Passengers mulled about, grasping the rails tightly as they walked. Some retreated into the stable belly of the ship, cautiously finding the way to their precisely accommodated cabins. Louise smiled at them as she passed, on her way to the outer deck. As the ship neared its approach toward the western coast of Norway, she wanted to take in the view with no obstacles.

Outside, she gasped for breath in the frigid air. The muted grey skies snubbed her enthusiasm, but they could not dull her mood. Winds weighed her down as she attempted to walk to the railing, yet she carried on with a bounce in her step. She flexed her fingers, chilled and nearly numb despite the faux comfort of their gloves. And yet, as much as the environment seemed determined to turn her away, Louise leaned in. The cold, drab, empty landscape somehow felt like home.

Ironically, Louise's actual home sat 3,500 miles away: a mansion in San Rafael, CA. Born in 1887, Louise grew up wandering gilded halls. Her father, John Boyd, escaped rural Pennsylvania with nothing but hope to guide him. Fueled by determination, he had a knack for mechanics and put his skills to use in mining. His hard work met with a stroke of luck when a mine that he’d invested in proved a golden success, earning him and his two partners millions of dollars. Luckier still, the two fellas that he’d partnered with on that successful mine introduced him to something even more precious: their niece became his wife, and she bore him three children, including Louise.

Louise lived a charmed life. She spent an idyllic childhood in San Rafael, wandering the hillsides and frolicking outside with her two older brothers. Their father raised them with a spirit of adventure, and Louise possessed a seemingly endless curiosity about the world. She collected rocks and leaves. Her pockets overflowed with specimens. She inquired constantly about nature’s many fascinations.

Until one morning, the spell broke. Louise’s eldest brother died in his sleep, the victim of a poor heart condition. His death weighed heavily on the family. And casting a shadow on a dark period: just months later, the same heart condition stole her other brother. Of their five hearts, two had failed, and the remaining three suffered in their absence.

As a suddenly and unexpectedly only child, Louise's parents doted on her, yet they also assumed she would take on the responsibilities of the eldest child. She accepted a management role with the Boyd Investment Co. She continued to live at home, following through with all of the social obligations of a high society dame: the galas, the fundraisers. Her pockets of rocks and leaves had been replaced by niceties and demure appearances. She carried on, living the life that was thought proper for a woman of her stature. Eleven years after the ache of her brothers’ passing, her parents also expired within a year of each other. Louise’s heart grew heavier. She inherited millions of dollars, yet she had lost everything that mattered.

Louise posed during her pre-explorer period.

'Photo: [https://www.elks1108.org/event/louise-boyds-birthday Marin County Elks Club

But she carried on, slipping silently into the life she assumed was expected of her: socializing, sponsoring charities, hosting lavish parties. But the weight remained, casting shadows upon her heavy heart. And then she did something that people, and women especially, rarely did in the 1920s: she got a passport. Her first stop: Europe. She joined a friend on the typical route through Spain, Italy, France... But it wasn’t until she went north that her heart started to flutter. On a pleasure cruise around Iceland, Greenland, and Lapland, Louise felt the spark of adventure and curiosity that used to fuel her afternoons with her family. Before she even arrived home, Louise began planning her return journey.

This time, she wanted to go on her terms. In 1926, she chartered a ship (appropriately named The Hobby) for a trip to Franz Josef Land in Greenland. Funding the trip herself, she organized a talented captain and crew, and arranged the necessary equipment and provisions. Among the supply list: dozens of cases of champagne. This was to be a decadent trip, but there was also an element of sport. Louise intended to hunt polar bears. And indeed, she shot one on her first attempt, to the joyous celebration of everyone aboard, as it had taken weeks to reach the coasts of Greenland, and they hadn’t eaten fresh meat in days.

Life on the sea, and especially on the ice, resonated with Louise. Dreary skies, torrential storms, tight, itchy knickers worn for days on end, risking botulism from canned food gone bad... The closer she got to death, the more alive she felt. And she was hardly home long enough to unpack her long johns before she began planning yet another trip north. In addition to funding the trip, this time she also charted her own course—quite literally, mapping the ocean waters and determining when and where to navigate the ship—and to the high praise of the captains she hired for the journey. A pleasant “Hobby” it may be, but this was also serious business. Just ten years earlier, Ernest Shackleton and his crew had nearly died, lost and stranded in the Antarctic for over a year. And here’s Louise, plotting her ship’s course as easily as she would organize a society gala.

Louise planned to meet the ship and her Norwegian crew in Oslo before departing for Greenland. But she learned some upsetting news upon her arrival in Norway. An Italian explorer, Umberto Nobile, had gone missing. The famous Norwegian Roald Amundsen led a rescue mission to find the Italians, and in a tragic turn of events, Amundsen and his crew had also become lost. Everyone in the polar community rallied, organizing a global search party with dozens of vessels to scour the Arctic in search of the two explorers and their crews.

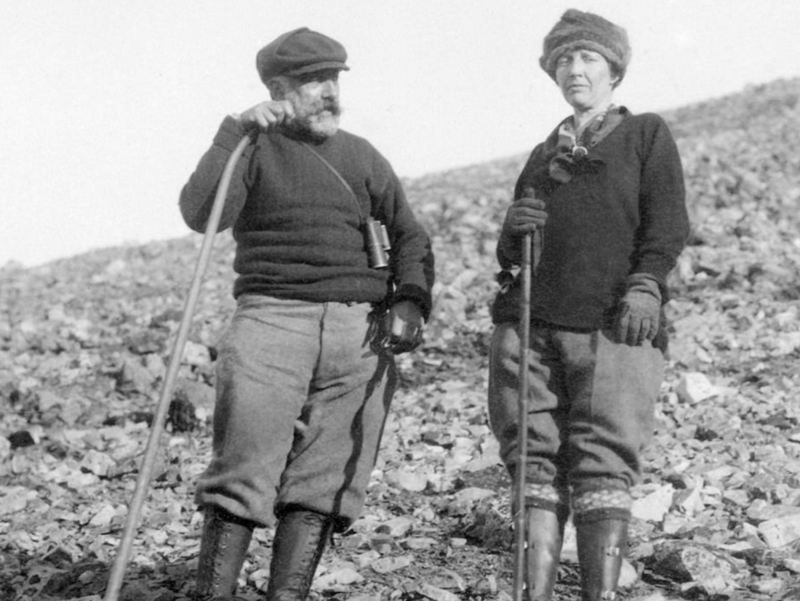

Louise Boyd and companion in Greenland.

Photo: Adventure-Journal.com

Louise could have gone on with her cruise, or she could have offered the ship to the search party and enjoyed a pleasant vacation in mainland Europe. Heck, she could’ve just gone home and lounged about in her mansion. As a proper lady, she insisted upon contributing her vessel to the cause -- and she didn’t hesitate for a moment before agreeing to stay on as the leader of her crew in the search efforts.

For months, she and her crew ventured into desolate regions of the Arctic, receiving directions from the global search party organizers. After ten weeks, they’d covered nearly ten thousand miles. One of the many search parties had located the Nobile crew, but Amundsen & his crew remained missing. As the weeks dragged on, days of endless sunshine gave way to the kind of slippery mental states that polar regions tend to inspire. Up to this point, Louise had lived a life of leisure. Even her journeys to one of the most difficult places on earth had been celebrated with fine champagne.

As members of the crew began hallucinating tent encampments on the ice, Louise started to understand the hazards of such extreme travel. In the tenth week, Louise and her crew received news that portions of Amundsen’s aircraft had been discovered. Amundsen and his men were presumed dead. The ice had won.

Louise returned to her estate in San Rafael, but not for long. Shortly after she arrived home, she received an invitation to return to Norway. The King wished to personally honor her with one of the country’s most esteemed awards: the Order of St. Olaf. As the first non-Norwegian woman to ever receive the recognition, Louise intended to accept this honor in style. Stopping off in Paris on her way to Norway, she purchased an elegant gown for the occasion. When she entered the vast hall to receive the King’s award, her crew were already inside—and despite having just spent ten weeks cramped into tight quarters together, they didn’t even recognize her!

Every time Louise returned home from the North, she immediately started planning her return to the tundra. Her ample experience in organizing events translated surprisingly well to her Arctic journeys. She thoroughly documented each expedition with detailed logs. She’d collected botanical samples from every landing site. She’d taken hoards of photographs. Although she had no scientific training, she had a natural eye for what mattered, and she’d taken photos of ice variations, landscapes, the shifting shape of the glaciers. Returning to the U.S., she shared her archives with the American Geographical Society, and they partnered on several more Arctic expeditions, generating photographs and data that remain useful for present day climate change studies.

In total, Louise Boyd completed seven journeys to the Arctic. She also traveled to remote parts of Eastern Europe, Asia & the Middle East. Along the way, she made significant contributions to science. She discovered new geological sites, including an underwater mountain ridge northeast of Norway. She pioneered a new method of aerial photography that increased accuracy of maps by 120 times. Her 1938 expedition landed further north in Greenland than anyone had before, and the Danish government named the area Weisboydlund, or "Louise Boyd Land," in her honor.

In the 1940s, she led an expedition at the request of the U.S. government. They approached her with a proposal for a covert mission to gather data about radio signals along the coast of Greenland. As it offered essential insight to assist the military in the war effort, Louise happily obliged. And just like that, the lady of the arctic was now a spy to boot. Louise led the classified mission under the guise of one of her pleasure cruises. Not even the crew on her boat knew the full extent of the ship’s mission. Her reputation as a well-to-do explorer allowed her to fly under the radar: “Oh, that’s just Louise off on another adventure…” Under this premise, the expedition gathered radio data, scouted landing sites, and provided charts and maps to assist Allied pilots in their communications with submarines.

Louise Boyd on her return from her successful flight over the North Pole.

Photo: Adventure-Journal.com

At the age of 67, Louise fulfilled her dream of flying over the North Pole. As the first woman to do so, the journey was especially remarkable. As she gazed down at "Louise Boyd Land," circling the world in a matter of moments, she reflected on all of the journeys that had brought her to that point. Louise had inherited her family’s wealth and her father’s sense of adventure. Having lost her family, she felt she’d lost a piece of herself. She’d wandered at first to ease the weight of her sorrow, and she managed to find a spot to call home—even if it was the edge of the earth.