Valencia Street, circa 1981, Bohemian Roots of Gentrification

Historical Essay

by Jeff Goldthorpe, 1981

Valencia Street, which runs south from Market through the mostly Latino, yet very integrated Mission District (and is only four or five blocks from the gay male ghetto of Castro Street) is a good illustration of layers. An old commercial street running through a poor working class neighborhood, it still has the old used car lots, cheap residential hotels, second hand appliances stores, furniture stores and the usual small grocery stores and taquerias. But this is no typical commercial strip.

Valencia Gardens public housing in 1996 between 14th and 15th Streets, Valencia and Guerrero, before its reconstruction.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

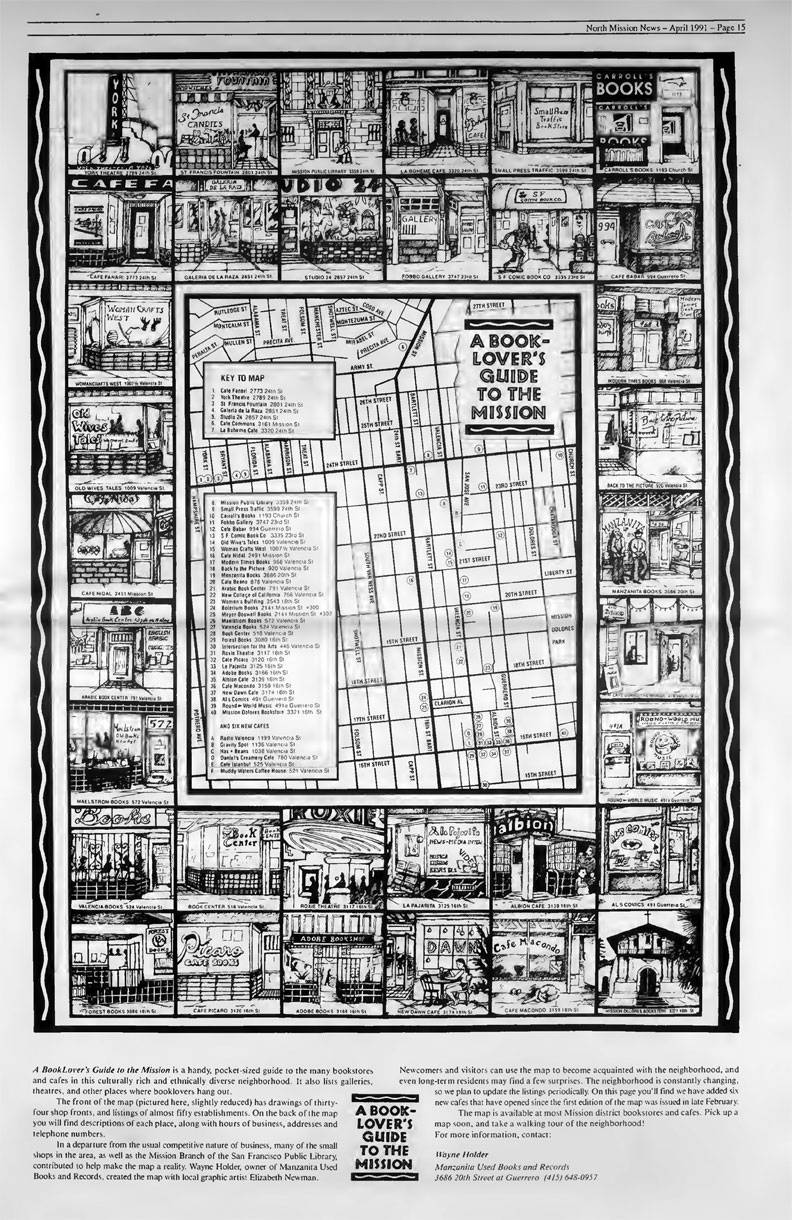

Just past Duboce, the 1981 walker encounters the American Indian Center, with its employment and counseling offices below and its auditorium above, site of many a concert, poetry reading and forum. Passing by the Valencia Garden projects, the walker reaches 16th and Valencia, whose chief landmark is the empty pit left from the Gartland Hotel fire in the mid-seventies. Adjacent to this intersection is the Roxie theater, an ex-porn theater specializing in independent and foreign films, the Picaro Cafe, the Compound, a punk shopping mall, a couple of good used bookstores and the Book Center, run by the Communist Party and a Casa El Salvador storefront. Closer to 17th Street is Subterraean Records, one of the main record companies for the local punk scene and the Deaf Club, site of some of the most exciting and eardrum blasting punk shows.

In the middle of the next block is Amelia's, a large bar/disco for lesbians, one block away from the Women's Building, a large four story building full of halls and offices, buzzing with activity. Across the street from the small alternative school New College is the Valencia Rose, a gay night club and community center, with a vital comedy and cabaret scene.

Past 20th Street is a block including a women's bathhouse, Cloud House, a gathering place for beat-influenced visionary poets, La Raza Graphics Center and gallery, Modern Times, an ecumenical bookstore for the left, Valencia Tool and Die, a funky art space with a basement for hardcore punk shows and The Offensive, a storefront with the same mission as Tool and Die. In the next block is Old Wives Tales feminist bookstore and Babylon Burning, a t-shirt store with one ear toward the punk scene. The last outpost of the counter culture at 23rd Street is the women-only Artemis Cafe.

Relations between the subcultures and communities represented here are not necessarily filled with mutual respect or even civility, but surely proximity makes paths cross and ideas pollinate. The problem here, as in any bohemia, is how to use this free space to escape one's obvious irrelevance to the larger world. Energy is there but resources are not, so one easily falls into the cult of bohemian failure, with grating poverty, alcoholism or drug addiction the obvious dangers. Some join the fight against their fellow artists, passionately competing for grants, scarce jobs in community programs or teaching posts. Many are forced back into the "real world" of the downtown financial district towering in the background, the university, or the latest brand of political realism for marginalized radicals, joining the local Democratic Party. Whatever the particulars, radicals and counter-culturalists living in this country club prison are often prone to disillusionment, and creatively original forms of hypocrisy.

However the most fundamental restriction of the space of the counter culture has been literal: the skyrocketing price of housing. During the mid-seventies, the Haight-Ashbury's revitalization turned into a full scale gentrification, precipitating the departure of many of the low income black, senior and hippie tenants there from the sixties. Real estate speculation became a popular sport as one third of Haight Street's commercial properties changed hands between 1976 and 1978.(1) The neighborhood, following the earlier decay and bohemian influx, was entering into a phase of middle class transition, characterized by the new, more affluent young homeowning professionals, displacement of older neighborhood businesses by chainstores and more upscale boutiques.

from the North Mission News, a decade later, September 1991

But unlike the early sixties relocation of North Beach bohemians to the Haight, paving the way for the hippie influx, the punk bohemia was scattered here and there among other non-conformist and low-income communities. Thus punks joined the competition for ever-scarcer housing, with its associated racial and cultural conflicts. On Valencia Street particularly, one could view the tensions between the Latino community to its east and the "bohemian influx" of young punks, and other low-income lesbians, artists, students clustered around Valencia. Just a few blocks to the west was a highly gentrified area. Punks may have despised the "yuppies," but clearly bohemias play an ambiguous role in real estate, as in culture, escaping middle-class suffocation in low-rent districts, which they ironically salvage for the hipper members of the middle class. In New York, punks and other new bohemians, aided by an early eighties "art boom," made the Lower East Side some the world's hippest, hottest real estate. Punks in San Francisco, attracted to the South of Market's industrial/slum/leather bar ambiance helped pave the way for the mid-eighties hetero-hip arty chic of SOMA (formerly South of Market, like New York's SoHO, get it?). On the other hand, punk in New York and San Francisco helped spark squatting activity, attempting to uncouple the counterculture from the new middle class. One place the sparks flew was next to the freeway dividing the north end of the Mission District from the South of Market, in an abandoned brewery.

1. Neighborhoods in Transition: The Making of San Francisco’s Ethnic and Nonconformist Communities, Brian J. Godfrey, University of California Press: 1988