Jello Biafra and the Dead Kennedys

Historical Essay

by Jeff Goldthorpe

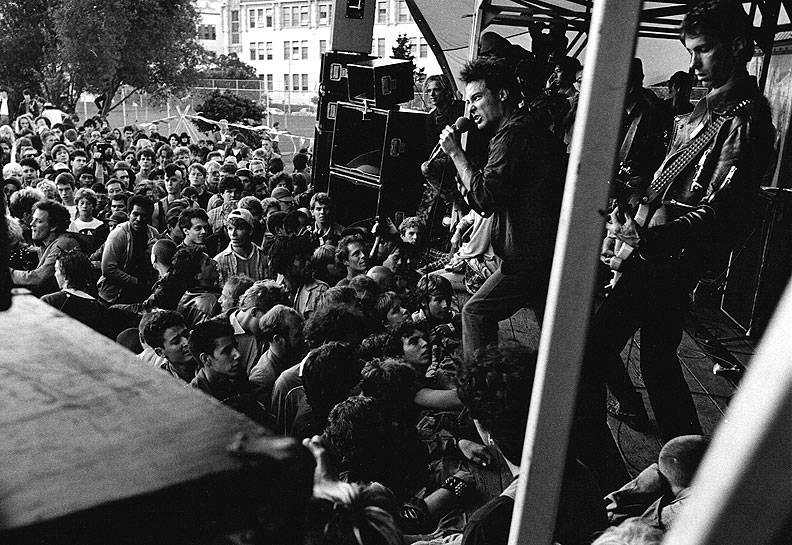

Jello Biafra singing in front of the Dead Kennedys, 1984 Rock Against Reagan concert, Dolores Park.

Photo: Keith Holmes

Following the Peoples Temple / Dan White events and the consequent political polarization, San Francisco politics veered to the right. The two frontrunners in the 1979 mayoral election were "moderates" who were clearly not going to offend the Police Officers Association as Moscone had, despite the controversy surrounding the police and the District Attorney's office for aiding Dan White. Jello Biafra stepped into this political vacuum, with a campaign platform both satirical (to "clean up Market Street" by requiring businessmen to wear clown suits and erecting Dan White statues around town to throw eggs at) and serious (halting skyscraper construction, stronger rent control, etc). Announcing his candidacy for Mayor shortly before the first Western Front Festival of punk music in the fall of '79, Biafra rapidly showed his skills as unofficial media spokesman and in-scene unifier. The campaign was a brilliant piece of political theatre (Biafra holding press conferences in front of City Hall and calling for clean politics by vacuuming in front of Mayor Feinstein's house), garnering a lot of local press coverage. The campaign was popular in the punk scene as well, not just for reasons of political sentiment (it certainly was a skillful meshing of punk sensibility and political satire) but also for the dreams of glory it evoked in some:

While attending a gathering at Target [Video, which produced tapes of punk shows aired on a local cable station as well as hosting numerous parties with live music], Damage editor Lapin loudly proclaimed, 'We have our own paper, our own television station (Target) and own candidate for mayor,' to the raucous applause of everyone present.(1)

Biafra made an excellent showing for a satirical candidate, coming in fourth in a field of ten, with 6,591 votes. In doing so, he was not only appealing to the same counter-culture voters who cast their ballots for the habit-wearing Sister Boom-Boom of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence in the Supervisors' race, he was also following the venerable S.F. tradition. In 1961, Jose Sarria, a drag performer in The Black Cat, a North Beach gay/ bohemian bar, had run for board of supervisors at the height of the perrenial police harassment of gay bars. Sarria also won about 6,000 votes and set the stage for the next decade's gay activism.

MEANWHILE, BACK IN SAN FRANCISCO....1980: THE DEAD KENNEDYS

Tenth Street Hall survived one of the hardest of hardcore evenings ever presented when L.A.'s Circle Jerks and Black Flag opened for the Dead Kennedys. That particular night, Biafra, always the showman, pulled a young skinhead wearing a swastika T-shirt out of the audience, to help introduce the Kennedys’ new song Nazi Punks Fuck Off. (2)

Although the Dead Kennedys never really wedded themselves to the thrash style, they rode the wave quite skillfully, becoming the most popular punk band in the Bay Area and well-known nationally and internationally as well. They identified with the populism and DIY ethic of thrash punk, reached out to the new suburban audience for punk, but in contrast to Black Flag, they attempted to limit the destructive meanings of punk from a left/anarchist perspective. The debut of their "Nazi Punks" song referred to above is indicative of the way that Jello Biafra used punk venom and sarcasm to criticize punk. The song was shouted out in perfect thrash style and the lyrics were printed in the recorded version, where it becomes clear that the song is not just about a political symbol, but addresses Greil Marcus' point about the punk "disinclination to think":

- Punk ain't no religious cult

- Punk means thinking for yourself

- You ain't hardcore cos you spike your hair

- When a jock still lives inside your head

- Nazi Punks/Nazi Punks/Nazi Punks/Fuck Off! (refrain)

- If you've come to fight get outta here

- You ain't no better than the bouncers

- We ain't trying to be police

- When you ape the cops, it ain't anarchy

- (Refrain)

- Ten guys jump on, what a man

- You fight each other the police state wins

- Stab your backs when you trash our halls

- Trash a bank if you've got real balls

- You still think swastikas look real cool

- The real nazis run your schools

- They're coaches, businessmen and cops

- In the real fourth reich, you'll be the first to go

- (refrain)

- You'll be the first to go/ You'll be the first to go/

- You'll be the first to go/ Unless you think!

- (Dead Kennedys)

A correspondence was established: punk = critical intelligence = against fighting= self-organized = against petty vandalism = against Nazi symbols = collectivist anarchism. None of this was understood as a major part of being punk up till then. This song was part of a larger attempt to fundamentally redefine punk. The motivation was not merely theoretical, for vandalism and fighting had plagued shows in both San Francisco and Los Angeles, forcing constant changes of venue as well as material losses and hospitalizations.

There had been various attempts to catalyze peer pressure to limit chaotic violence. In late 1980, Greg Ginn of Black Flag argued that,

"Violence between individuals at the gigs has lowered considerably in the last six months...People are getting the idea that its stupid. You might find a few fights but its less than you'd find than at the corner bar on a weekend… We encouraged people to cut loose but we don't encourage violence,' added Ginn, who traces the origins of punk violence to the battles between the new punk community and the long-haired 'jocks' in the South Bay a few years ago." (3)

But the attempt to establish a boundary between dance ritual and violence, between "cutting loose" and vandalism was not easy, for a pattern had been set, expectations established and a scene had developed that walked a tightrope of seemingly violent ritual, always on the edge of becoming the real thing. An artist in the Incite! group, who had gone through the earlier hippie, glitter and punk scenes, hung around, was skeptical about the new scene:

The 10th Street Hall New Year's gig that Paul Rat put on had Black Flag , an all hardcore bill. It was jammed. It was much more violent in tone; not just if you were going to be up front, where there was a tremendous amount of thrashing and throwing of beer cans, but also people being rough away from the dancing area, pushing and shoving. Everyone was doing lots of speed and drinking a lot at those things. We were [on speed], people were asking if you had any. It gives you energy, makes you sped-up and edgy and you can drink—you're a wide-awake drunk—alcohol has that release of inhibitions. With the attitudes in the music and dress all very aggressive and hostile. (4)

The earlier punk scene had been “more eclectic, mixed in with other kinds of fringe parts of the culture. There were people who had mohawks, leather and chains but a whole lot of people with skinny-lapelled coats, more of an art scene crowd. (5)

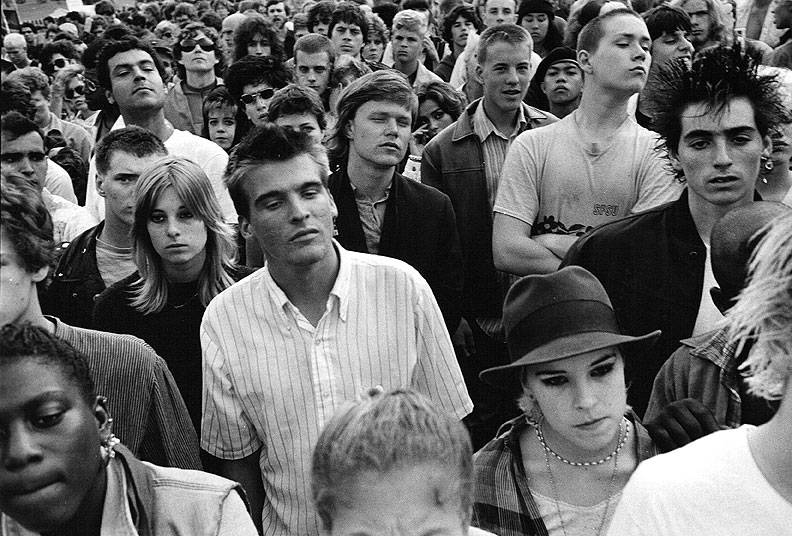

Watching the Dead Kennedys at Dolores Park at the Rock Against Reagan Dolores Park show, 1984.

Photo: Keith Holmes

The Dead Kennedys answer to the violence of the new thrash scene was to try to make critical thinking, non-violent ethics and rituals, subcultural self-organization and anti-authoritarian politics part of the definition of "punk."

But even in the DK's early music, a tension existed between critical and nihilist impulses, between violence and tolerance, between skepticism and faith. While Biafra excelled in fiendish parody, donning various personas, the DKs played with menace and dread just as much as Black Flag. Biafra took on roles as anti-middle class rebel ("Let's Lynch the Landlord" and "Chemical Warfare"), ultra-alienated youth ("Drug Me" and "Looking Forward Death"), murderer/madman ("I Kill Children," and "Funland at the Beach") and ruling class manipulator ("Kill the Poor). Musically, the DK's were more traditional than Black Flag or Minor Threat, drawing on demonic psychedelia and even rockabilly riffs, ranging from slap-dash thrash to the abrupt slowing of musical pace, where tensions are slowly built up and released in periodic torrents. On stage, Biafra conjured up an atmosphere of a B-horror movie, mixed with one part Cabaret (1972 movie about "decadent" Weimar Berlin with very scary stage acts by Liza Minelli and Joel Grey) and one part Wicked Witch of the West.

Theatricality and the presence of the satirical voice is probably the main difference setting off the DK's from Black Flag. While Biafra's gestures and singing sought to produce either shock or audience identification with the voice in each song. no matter how destructive the impulse, the roles switched rapidly, creating a critical distance for the audience to see them as plainly theatrical. Live, the DKs, mainly lead singer Biafra, were more "showy" and theatrical and less casual and "real" than Black Flag was. Yet through all the changes in character, the audience had a clear idea of Jello Biafra's own iconoclastic personality. Like children hearing a scary story and willing themselves into mock-terror, they allowed themselves to be driven into a slam dancing frenzy by Biafra's theatrics and the DK's crescendos of sound. Marian Kester wrote quite cynically about the lead singer's charisma:

“California Uber Alles" probably works the same juices that "Deutschland Uber Alles" did during its day in the sun...Biafra hectors the crowd with their ignorance of history, exhorting them to resist racist fascism and fascist racism; meanwhile he dictates absolutely from the stage, secure like all dictators in his ability to arouse our avatisms and possess us through them (6)

Kester has caught Jello, and every other charismatic performer, in the act here. Their power is fearsome. Unless they are to retire from the stage, all we can do is ask if these performers, as they seduce us, let us see that they are on stage through our power, giving us some critical distance.

True, Biafra was fond of pacing the stage between songs, berating and chiding the crowd for its conformism or drug-induced apathy and encouraging his hooting, despising, adoring crowd to think about approaching social conflicts in apocalyptic terms. “I know you're so drunk by now you don't give a shit that the police are picking kids up on Polk Street, beating the shit out of them and dumping them in the suburbs. You won't give a flying fuck till you feel their big oak sticks poking up your butts. Look, I know a lot of you are going home to listen to your Joni Mitchell records....”

But Biafra had a secret agenda: to make these loveless punks care about each other and think about their behavior. He would halt a song at the drop of a hat when a fight started and denounce those who wouldn't give stage divers a soft landing.

Speaking of "California Uber Alles," the DK's recomposed their first big hit as "We've Got a Bigger Problem Now" after Reagan's election (see In God We Trust EP, 1981). This new version interspersed the hyponotic rhythm of the original and grafted in sequences of cocktail jazz muzak, with Jello presiding as bartender/therapist:

- Last call—drink up

- Last call for your freedom of speech

- Happy hour is now enforced by law...

- That's it, just relax, have another drink,

- A few more pretzels...little more MSG,

- Turn on those Dallas Cowboys on your TV.

- Lock your doors...close your mind, it's time

- For the three minute warning...

- (Here the band explodes into onrushing thrash, Biafra roaring:)

- WELCOME to 1984/ Are you ready for the third world war?

- (1981a)

The DK's performance of this song was a clear example of the possibility of plunging into punk frenzy and maintaining a critical self-awareness at the same time. For every time the onrushing thrash sequences segued into the cocktail jazz, Biafra had an audience of tipsy slam dancers catching their breath, focusing on the stage, trying to figure out what this band was doing, and taking in Jello's sarcastic homilies. On their records lyrics were always included, along with Winston Smith's brilliant political collages, in case fans still hadn't gotten the point.

1986: HIGH-TECH LAID LOW, OR THE REAGANAUTS DO CRASH LANDING

The Challenger Space Shuttle was the spectacle par excellance: this magnificent image that we looked up to, dwarfing our petty ambitions with its cosmic lift-off, the power to which we have entrusted our lives. As much a creature of the Pentagon as NASA, it was also a flying advertisement for Reagan's Star Wars system, proof of technological invincibility, something to trust. The trust of millions of school children was placed on Teacher/Mommy figure Christa McAuliffe, who would hook a whole new generation on high-tech with a human face. We were flying high as it roared up to the heavens and poof! there was bright orange flare, the ricocheting bits of...Omigod, it can't happen here. Christa had told us it was completely safe. The fear and doubt of those ten seconds could only be allayed by hours, days, weeks of media hype and electronic hugs, "bringing the nation together" in a way unseen since the Iranian hostage crisis. Reagan knew how to put the right spin on it. Using a heroic couplet penned by a young flyer killed in World War II, he convinced most Americans that in this flight into the stars, no sacrifice was too great. Doubts about the reliability of an impenetrable space shield of satellites and laser beams hovering over the U.S.A. were buried in the subconscious and we marched on.

Jello Biafra was therefore only continuing his tradition of topical commentary between songs when he read "Why I'm Glad the Space Shuttle Blew Up," noting that the next shuttle was scheduled to carry a large load of plutonium. This was not a concert with the Dead Kennedys. Rather, he was in early 1986 beginning to do his own "spoken word" performances, looking for a more cerebral outlet, as were other punk singers, such as Exene of X and Henry Rollins of Black Flag. Jello began his performance in a darkened auditorium at S.F. State University by simulating a New Age relaxation tape which turned out to prepare the listener for his/her fate as an Easter turkey baking in the oven. Continuing a taste exhibited as far back as his 1979 "California Uber Alles," he combined B-movie horror aesthetics with lead pipe irony. His second piece was a Big Brother employer automating a worker out of a job: "You are powerless and we'll make you love it. Don't kill yourself in front of the tourists, " inducing wild laughing and cheering from an adoring audience. As his name suggested, Jello's strong point was his placement of innocent, familiar items of pop culture into a malign universe. In a commentary on widespread efforts to put the Vietnam Syndrome behind us, Biafra sketched out a plan for a Vietnam Amusement Park, selling items such as "Hefty Brand Designer Body Bags." Biafra left his audience on a positive note, asserting in contrast to Rambomania that "caring is the real test of strength." But these admirable sentiments had no power after the horror show, never giving its listeners a moving illumination of why caring or honesty or idealism was better than work-a-day callousness.

April 1986 was a busy month for Jello Biafra. On April 15, nine Los Angeles and San Francisco plainclothes police raided his S.F. apartment, also the office of Alternative Tentacles Records, searching for copies of the Dead Kennedys recent album Frankenchrist and other incriminating evidence. By June 2, Micheal Guarino, a Los Angeles deputy district attorney charged Biafra and associates with distributing material harmful to minors. The prosecution had been touched off by a mother's complaint about Frankenchrist, which included a reproduction of a disturbing but not very sexy painting called "Penis Landscape," bought by her fourteen year old daughter. Guarino spoke of the case as a "cost effective way of sending out a message." True, the Dead Kennedys did not have the legal resources or media clout of a popular rock band signed to a major label. But Guarino may not have known that he had picked on the punk musician who had won 6,500 votes in a 1979 run for San Francisco mayor and had since distinguished himself as best political agitator in the hardcore scene, as well as one of the most popular performers.

Immediately the [right-wing] Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC) hailed the prosecution, charging that the album was "pornography." The target was ironic, since the album wrapper had a warning sticker on it, as the PMRC's demanded, which had become a common sight on rock albums in the year after the PMRC/Senate hearing (although the sticker sneered, "The inside fold-out to this record cover is a work of art by H.R. Giger that some people may find shocking, repulsive or offensive. Life can sometimes be that way").

In response Biafra and others organized the No More Censorship Defense Fund, garnering support from anti-PMRC musicians like Frank Zappa and Steve Van Zandt, the anti-PMRC Musical Majority and civil liberities groups like the American Civil Liberties Union and the National Coalition Against Censorship. The Dead Kennedys continued to distribute Frankenchrist, substituting a fact sheet on the case and its politics for the offensive poster, and also produced a new album with a similar broadside enclosed, Bedtime for Democracy. With the band the case led to a drifting apart. Although he has referred to suicidal urges during this period, Biafra went on the offensive, continuing his spoken word performances and simple speeches on his case, speaking to the press, popping up at the industry's New Music Seminar, even publishing an article in the Harvard Law Record, as well as attending to the details of his own case.

His August 1987 acquittal was certainly a major victory against the "porn rock" crusade. On the other hand, it did not turn the tide either. The PMRC's labeling system has become popular, if not its rating system. Record companies increasingly pressure musicians to censor themselves, such the Beastie Boys alterations of their License to Ill album demanded by CBS records. Some record store chains like the Sound Wherehouse not only banned the Dead Kennedys but purged a dozen other albums with "satanic" tendencies. Local arrests of record store clerks, legislation resticting minors' access to rock concerts and local campaigns against "offensive" books in schools continue. Public and college radio stations have come under increasing restrictions from the Federal Communications Commission at the threat of losing their licenses (Richardson, 1987). The furor over the Supreme Court's ruling that flag burning is protected as free speech (based on an arrest made at the 1984 War Chest Tour at the Republican Convention in Dallas) is instructive about where things stand. The strength of the belief in the Bill of Rights has blocked fundamental forms of censorship and yet George Bush was able to successfully use the flag burning dispute as a "issue" in his presidential campaign, pressuring Dukakis to recant his liberalism!

Notes

1. Hardcore California: A History of Punk and New Wave, Peter Belsito and Bob Davis, Last Gasp, San Francisco: 1983, p. 106.

2. Ibid. p. 110

3. Cromelin, Richard, “Southland Punk Discs: A Primer,” Los Angeles Times, July 5, 1981.

4. Incite! Interview, 1988

5. Ibid.

6. Dead Kennedys: The Unauthorized Version, edited by f-Stop Fitzgerald and written by Marian Kester, Last Gasp, San Francisco: 1983, p. 36