Organizing the Mission District Before the MCO (1964-1968)

"I was there..."

by John Ross

John Ross celebrates his 70th birthday at Cafe Boheme on 24th near Mission, March 2007.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

I - TOUCHING DOWN

I touched down in San Francisco's Mission District on a sun-flecked winter morning in January 1964 fresh in from the Michoacan outback where I had been living for the past seven years or so. Like many who today gather along Cesar Chavez Boulevard, I was looking for work to send money home to my family, any kind of work.

I scoured 24th Street for odd jobs. Potential employees couldn't figure me out, a white boy who spoke street Spanish like a native. I explained I was a "whiteback," a gringo with a wife and a kid in Mexico to feed. Did they have anything for me? The negatives were universal.

By mid-morning my guts were barking. I tallied my coins and bellied up to the counter at the Sunrise restaurant between York and Bryant for nopales and eggs. Later, we would know the Sunrise as Margarita's, named for its soft-touch owner with a golden voice who opened her doors to grassroots political groups and had her own show on KPFA for a while. Today, Margarita's is a Mexican torta palace.

The counterman didn't think Margarita needed a dishwasher but tipped me about employment opportunities further down the street.

Between Capp and Mission I noticed a storefront (it's now a florist stand) that had Mexican puppets hanging in the window. Back home, I had always been taken by the street puppeteers who walked the big city streets hawking their wares. I demonstrated my skills for the owner and he agreed to front me a dozen puppets if I could get a permit from the city to sell on the street - but the permit price proved prohibitive.

"Here, you can sell these." Carlos, the store owner, took pity on me and thrust a clutch of 1960s Spanish-language girlie magazines into my mitt. "Try the Mexican barbershops on Saturdays," he counseled. I guess you could say selling the girlie magazines was my first community work on the streets of La Misión.

From the barbershops, I moved up to the California Missionary Army, a scam run by two fast-talking hustlers from Detroit out of offices on Mission between 21st & 22st Streets right about where Dr. Leroy, the venerable chiropractor, cracked backs for years. All you needed to enlist in the California Missionary Army was a dark suit (it didn't matter if it was mis-matched) and an ability to snivel and beg. The hustlers gave you a kind of ensign's cap and put you on the street.

We were knocking up doors woofing on the occupants to cough up a buck or more to "place bibles" - it didn't much matter much where ("gas station restrooms" was my line.) The majority of the crew was black, recent graduates of San Bruno, and we worked the avenues and the white suburbs where we were paid to go away by harried housewives whose hubbies were due home from work any second and didn't want us on the premises when they did. You could keep 60% of the take.

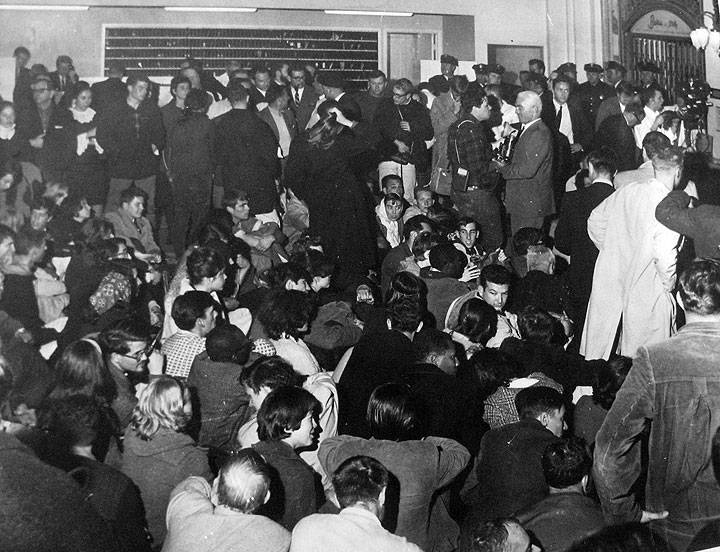

On the weekends, I would desert the California Missionary Army to lie down at the Sheraton Palace Hotel or Van Ness auto row at tumultuous civil rights demonstrations sparked by the 18 year-old firebrand Tracy Sims and the Ad Hoc Committee Against Discrimination.

Protesters engage in a sleep-in after 200 arrests, March 7, 1964, during the civil rights protests at the Sheraton-Palace Hotel.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

The FBI ran me to ground after my fourth or fifth civil disobedience arrest. I had torn up my draft card and sent the shards back to the Selective Service after Eisenhower invaded Lebanon in 1958 and gone off to Mexico. Now it was Vietnam time and I became the first resister to serve federal time for refusing induction. A team of agents led by one Ralph J. Fink (sic) surrounded the hippie house where I was holed up on Mullen Avenue near the top of Bernal Hill and after some intense political theater I was on my way to Terminal Island Federal Penitentiary, San Pedro Calif, for a year.

II. THE REVOLUTION COMES TO THE MISSION

"When the prison gates open up, the dragon will fly out," Ho Chi Minh rhapsodized in a poem that George Jackson quotes in "Blood In Your Eye", and by the winter of 1965 I was back on the streets of the Mission, a fire-snorting Marxist-Leninist-Stalinist-Maoist revolutionary warrior in the ranks of the quaintly-entitled "Progressive Labor Party," actively plotting to overthrow the imperialist dog government of the United Snakes by any means necessary (and a few that weren't.)

Our chosen field of battle was "the community"—in New York City, PLP worked closely with Jesse Gray, the Harlem rent strike organizer, and he became our role model. We began pounding the backstreets of La Misión looking for rats and roaches and rent-gouging slumlords to unmask the evils of slime-bag capitalism.

So it was that one spring night in 1965, while we were out trolling Shotwell Street between 15th & 16th, Comrade Max Beagarie stepped out of a darkened doorway and signaled bingo! Because he had a Spanish speaker, I was called in to officiate.

Luis Melendez was a Puerto Rican nationalist and his first floor apartment was a rattrap. When you turned on the lights, the cockroaches went into stampede mode. There were 16 units in the building and every tenant had a sad story to tell. All of the tenants were Latino. Some had lived in the building for 15 years and told us that we weren't the first agitators to try and organize the tenants. The word "communist" was mentioned a lot. We weren't communists, were we?

The apartments were in escrow and the real estate company that managed them would make no repairs. We pulled together a meeting in Luisa Diaz's apartment. Luisa was a natural leader with a large and feisty family and we began banking the rent to make repairs under two sections of the California Civil Code whose numbers incipient Alzheimer's have obliterated. The rent strike went on for over two years although most of the tenants just took the money and ran.

24th and Shotwell, c. 1982. Not quite the same time as Ross describes, but a sense of Mission architecture and delapidation, albeit a bit later in time.

Photo: Dave Glass

Shotwell was a fecund enclave in which to organize in 1965. We staked out a corridor extending from the freeway to 16th Street and bounded by Folsom and South Van Ness. The firetrap housing was dilapidated and overrun with household pests. Because rents were relatively cheap (we paid $42 for a back cottage between Folsom and Shotwell), refugees fleeing Fillmore redevelopment had begun moving in and there was an uneasy truce between blacks and Latinos in the bars and on the blocks.

III. - THE MISSION TENANTS UNION

By now, we were calling ourselves the Mission Tenants Union, a wholly owned front group of the Progressive Labor Party, and we rented a garage across the street from the rent strike and turned it into a clubhouse. We continued to canvas the Mission and people called up when they were about to be evicted, their furniture already in the street, and we showed up and confronted the deputies and put their stuff back inside.

When we got a call, we would send out a member to get the details and invite the complainant to attend the next MTU meeting, impressing upon them that we were not a service organization, that they had to participate. When and if the aggrieved tenant showed up, their "case" was hashed out collectively and actions projected: picket lines and pressuring the city to inspect the premises. Rent strikes were always a last resort but sometimes we would have three or four buildings on strike at once. We awarded slumlords Golden Rat trophies or hunted them down at their posh homes on the peninsula.

Florida Street near 24th, 1982.

Photos: Dave Glass

My then-wife, Norma Melbourne, was a kick-ass organizer. She talked truth to authority with authority and because she was on welfare, was a natural magnet for the women in the neighborhood who were being hassled by the department, frequently assembling them at the welfare buildings on Otis and Mission Streets to ventilate their grievances.

In a ploy to get health inspectors into the apartments on Folsom and Shotwell, we began paying the kids a penny a cockroach until we had filled up a half dozen milk jugs with the creepy crawlers and took them down to 101 Grove to get Health Department director Dr. Ellis Sox's attention. "Get the Black Flag!" he squealed in terror when Norma released the beasties into his office carpet. Channel 7 got film. For years, Norma was known as the Cockroach Lady amongst the downtrodden of the Mission.

In February or March of 1966, a construction material warehouse went up in flames on Folsom near 16th and the streets filled with fire engines. The neighbors, fearful that the blaze would spread, piled onto Shotwell with all their belongings. Amidst the chaos, a gaggle of teenagers—Skippy, Lucky, Money, and Dickey Lucero—jumped up on the front steps of a nearby house and took over our bullhorn to demand a park right there where the warehouse had burnt to the ground.

We approached the Parks Department but were brushed off as is de rigeour. The Parks & Recreation Commission met each month out in Golden Gate Park at the elegant McClaren Lodge so Norma rounded up the neighborhood toddlers and we drove them out there and bought them all ice cream and turned them loose at the meeting, their cones dripping all over the expensive furniture. The mini-park proposal went straight to the top of the agenda and when the department dragged its feet, we returned, ice cream cones in hand. We got the mini-park, the first in the city under Joe Alioto's ham-fisted administration. The older kids even got summer jobs as mini-park monitors.

Mission Tenants Union picket line, c. 1968.

Photo: El Puente de Claudio

The Mission Tenants Union liked to party down with frequent tamale feasts up at Luisa's place. Each October 3rd, the feast day of San Francisco de Assisi, we threw a big-time street fiesta. One year, Luis Valdez brought the Teatro Campesino to Shotwell. The Artists Liberation Front daubed the faces of neighborhood kids with psychedelic motifs at the apex of the Hippie rage. We showed the great proletarian classic "Salt of the Earth' on a neighborhood warehouse wall.

Contracting for the musicians was always a hassle. We would take up a collection to pay for the mariachis but by the second year, the black people in the neighborhood wanted soul music and wouldn't kick in. We solved the problem by hiring a latino band out of Mission High whose big number was the Miracles' "Mickey's Monkey." The group called itself the Malibus and Carlos and Jorge Santana were two of its featured players.

IV. WAR ON THE POOR

By 1966, the War On Poverty had come to San Francisco and local Economic Opportunity Councils were created in so-called minority neighborhoods like La Misión. Open elections were held for Council members and the PLP puppet masters who pulled the MTU's strings decided that we should run candidates to expose Johnson's War On The Poor from the inside. Three of us—myself, Betsy Duncan, a near-blind Black woman from Bernal Hill, and Jay Frank, a young, gung-ho PLPer, won seats (I was the top vote getter in the district.)

The feeding frenzy of those heady days is snidely recorded in Tom Wolfe's "Mau-mau-ing The Flackcatchers" which focuses on grassroots Samoan groups. Money, a lot of money, was suddenly available to Mission social activist groups and everyone demanded a piece of the action. It often got ugly.

The Counsel, which met weekly in what was once Gold's Gym and is now an art gallery on Valencia, was itself quite representative of the Mission mix: Mexicans and Central Americans and Filipinos, Blacks and Native Americans—Jay and I were the only white radicals. Everybody and their grandmother had a project they wanted funded and sometimes us commies would be forced to cast the decisive vote. It was not a comfortable space for Revolutionary Marxist Leninist Stalinists Maoists to move in.

One rainy night at district elections to renew the board held at the American Indian Center on 16th, Skippy, Lucky, Dickey, and Money showed up and nominated themselves for seats on the council. They explained to the electorate that they were trying to go straight and didn't want to steal purses anymore but if they were not elected they wouldn't have any choice.

The kids didn't succeed in convincing their neighbors but Economic Opportunity Program organizers got wind of their intentions and one in particular, the Very Reverend Jesse James (sic) paid a rare visit to Shotwell Street—the EOP had red-lined our enclave as commie-held territory and did not often cross the turf lines. The Very Reverend Jesse James invited Skippy and Lucky and Dickey and Money to put together a Mission youth group. Oodles of dead presidents would be at their disposal, which is how the Mission Rebels were born. By the mid-1970s, the Rebels were running the city's food stamp program. A lot of Mission history has its roots on Shotwell Street in the '60s.

V. ALIOTO'S SWINE

Joe Alioto ran the city with what is called a "hard hand" ("mano dura") in Latin America. He used the SWAT squad as his own personal Praetorian Guard and his killer cops could do no wrong.

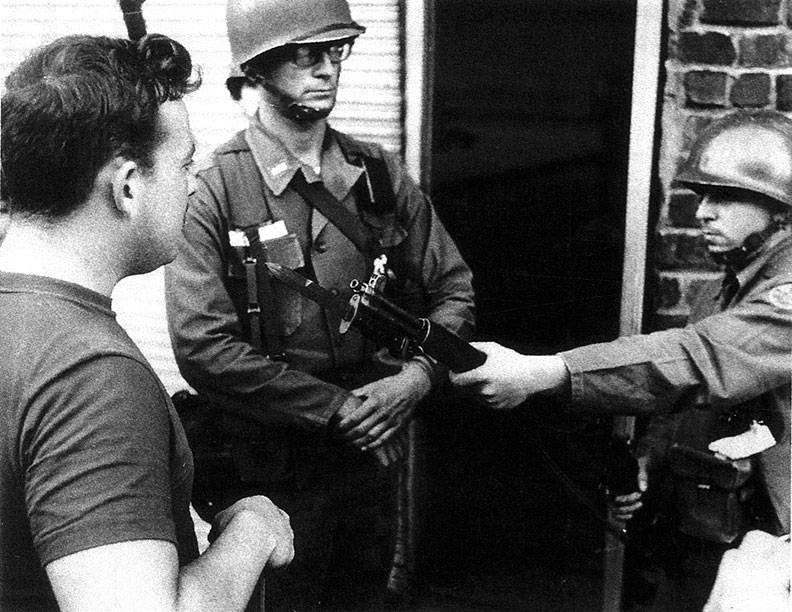

When Hunters' Point went up in flames in September '66 after an Alioto death squad executed a black teenager, then-governor Ronald Reagan sent in the National Guard. They bivouacked at the old armory on Mission and 14th, now the hub of the Kink Inc. porno empire. We called out the neighborhood to surround the fortress-like building and prevent the troops from vamping on our brothers and sisters at the Point. A couple of hundred protestors turned out including the nascent Mission Rebels. When the Guardsmen sought to deploy, we blocked the great armory doors—Jay Frank caught a bayonet.

Progressive Labor Party member Jay Frank confronts National Guard at Armory door, September 1966.

Photo: El Puente de Claudio

The Mission Station pigs would not get off the peoples' backs, rousting and beating on anyone whom they deemed a threat to their brutal hegemony. Despite ACLU intervention, I was repeatedly busted for posting incendiary literature on lampposts or selling the PLP paper "Spark/Chispa" ("one spark will start a prairie fire.") "We put people like you up against the wall and shoot them in my country," Sergeant Roy Hooper, a native of Panama, mentioned while he booked me at the old Mission Station.

In the '90s, after the station on Valencia between 24th and 23rd had been converted into a design studio, my daughter who was then working there, invited me in to visit. She showed me the holding cells that the designers had preserved to rent out as a movie set. "You don't know how many times I was brutalized here," I reminisced to Carla. "You're not the only one," sighed an electrician who had been fiddling with wires in the corner.

VI. "RENT CONTROL NOW! OUT OF VIETNAM!"

In 1967, the PLP District Committee (of which I was a member), intoxicated by my success in the Poverty board elections, sought to convince me that I should run for the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. The goal was once again to expose the rottenness of the capitalist system from inside the belly of the electoral beast. "We don't really want to win," my comrades insisted.

By then, relations between the ideologues on the district committee and those PLPers working with the MTU had grown raw. We were accused of disregarding class contradictions, abandoning the revolution, and applying band-aids to the festering sores of U.S. imperialism. To end the internal wrangling, I succumbed to the ideologues' nutso entreaties and registered as a candidate.

PLP cranked up the campaign. It was sort of embarrassing to see my mug hanging (illegally) from every light poll. I was confused: were we trying to turn things around here in the city or was I the fulcrum of Global Marxist Leninist Stalinist Maoist revolution?

Rent Control was our theme song and we sang it at raucous street meetings Friday evenings on Mission and 16th—the crowds swelled when the Muni riders changed buses—and out on the Miracle Mile on Saturday mornings from the bed of a pick-up truck parked in front of Value Giant. My old camarada Roberto Vargas, then building the Brown Berets, parked across Mission by Wells Fargo and the duel of the bullhorns brought traffic to a stop.

The summer of '67 was the long, hot one. Inner city rebellion blossomed in Newark and Detroit and tensions ran electric here in San Pancho. In early August, Mission Station goons came down on kids in the neighborhood whose only crime was sitting on a Shotwell Street stoop. We called out the mothers and put a bunch of baby strollers in front of the dread police station. The rally was spirited—we photographed one plainclothes cop photographing us and ran him back into the building.

That night, the pigs paid us back in spades at an anti-draft party on 15th & Dolores. A dozen black and white squad cars massed in the street. The arresting officers made it clear whom they had come for and busted down the front door. The cops had just been issued Mace and they emptied their canisters on us. I was dragged down the steps and the comrades came and rescued me. Prolonged fisticuffs ensued and the pigs began firing in the air. Juan Gonzalez, a gorilla who functioned as the Mission Station community relations liaison with whom I had often gone nose-to-nose at poverty council sessions whupped me repeatedly in the left eye with his flashlight—I eventually lost the eye.

Ten of us were arrested on a total of 70 felonies and countless misdemeanors. We made banner headlines on the Chron front page Monday morning. KRON interviewed me in a blood-spattered strip cell at the Hall of Injustice down on Bryant.

I had just registered as a candidate for the Board of Supervisors and one consequence of all this hoopla was that a candidate with a similar name—Tom Ross, publisher of the San Francisco Progress, a downtown Chamber of Commerce throwaway rag—noted that I was a convicted felon (refusal to report for induction in LBJ's killer army), which in those bad old days barred me from the ballot.

The City Registrar refused to return our filing fee when he marched into his palatial offices. So we printed up little stickers that read "JOHN ROSS—OUT OF VIETNAM/RENT CONTROL NOW!" and urged voters to paste them on their ballots. The day after the elections, the Chronicle ran a squib noting that "John Ross followers" had been arrested for "tampering with the voting machines."

In the final analysis, the PLP strategy of exposing the futility of electoral politics from within proved a successful one—but really, how many folks who tried to vote for me didn't know that already?

The "John Ross followers" schtick assaulted my political sensitivities—I don't want any fucking followers! Post-electoral skirmishes grew shrill on the district committee. The MTUrs were reviled as "reformists" which was about as low as you could go in the PLP pantheon although "revisionists" were probably still one circle of hell below.

How could we win the masses to the revolution by hiding our politics, the ideologues taunted? They had a point—we were chicken to the bone that we would be unmasked as commies and lose our few community recruits if we did.

One night I was up at Luisa's when the FBI punched up the doorbell. They showed her photographs of PLP members and asked if she knew that we were communists? "But they're such nice people" I heard Luisa respond.

VII. A RUNAWAY TRAIN

Once Justin Herman's bulldozers had finished with the Western Addition, Mission redevelopment was next. The Trojan horse was BART—the 16th to 24th Street corridor would be condominiumized. We saw the blueprints. Palm trees would bloom up and down Mission, a telltale sign of impending gentrification—that the trees did not flourish has more to do with cheap wine and poor peoples' piss than anything we tried to do to monkey wrench them.

BART was a runaway train and PLP and the MTU could not stop it alone. We needed to build alliances with other community forces even if they had sold out to Alioto and/or the EOC octopus.

Mike Miller seemed like a nice enough white guy, a community organizer who had headed Bay Area Friends of SNCC during the heyday of the civil rights struggle but when Stokely kicked all the white folks out and advised them to go organize in their own communities, Miller concentrated his considerable energies on La Misión.

Mike Miller was a coalition builder trained in the Saul Alinsky School that had produced Fred Ross and Cesar Chavez. He abided by the fundamental Alinsky organizing principle of rallying people around the lowest common denominator. Much like Alinsky and Chavez, he exhibited pernicious anti-communist tendencies. From the get-go, PL and the MTU were excluded from his prospectus.

We had been red-baited by the Alinskyites before. Cesar's compinche Fred Ross had shown up outside Purity (now Delano) on South Van Ness with two busloads of Filipino farm workers and pulled us off the grape boycott because Cesar didn't want any reds meddling in the movement. When a handful of us MTUrs—my wife and Betsy Duncan among them—tried to join the march to Sacramento in 1966 after a Poor Peoples' Convention in Fresno, we were unceremoniously told to go home.

The Mission Coalition on Redevelopment and later simply the Mission Coalition Organization (MCO) was a de facto Alinskyesque coup. Despite Sharon Gold's (now Martinez) heroic intervention, Miller managed to marginalize PLP and the MTU and we were never a factor in shaping the MCO or its class sensibilities.

A year or so later, I was a witness to the Mission Coalition's founding convention at St. Peter's Church on 24th. Even before the benediction was read, the Mission Rebels stormed the stage and threw the organizers into the audience, pissed off because they had been slighted in the organizing process.

But by then the struggle had moved on for me. Chicago had blown up and the whole world was watching. The bombs were beginning to fly. PLP had decreed that all able-bodied males had to get union jobs and prepare the proletariat for the coming dictatorship—we gave the revolution 15 years. Community organizing was deemed womens' work.

The San Francisco State strike exploded and the MTU was forgotten. We fell months behind in the rent. In the spring of 1970, Luisa Diaz locked up the clubhouse on Shotwell and turned the key into the landlord.

John Ross refuses his honor at City Hall, 2009.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

John Ross has lived in the old quarter of Mexico City for the past 25 years and is the author of ten books, the latest of which "El Monstruo—Dread & Redemption in Mexico City" published by Nation Books in Fall 2009. Ross was recently honored by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors for a lifetime of activist journalism. He refused the honor, asking instead that his filing fee for the 1967 election be returned. With interest.

John Ross died January 27, 2011.