AIDS Epidemic and Day of the Dead: The Overlooked Connection

Historical Essay

by Kirk Stevenson, 2019

This article originally appeared in El Tecolote, October 2019.

Juan Pablo Gutierrez, a LGBTQ artist and activist who serves as director of the Colectivo Del Rescate Cultural, on Oct. 19, 2019.

Photo: Sophia Schultz Rocha

San Francisco’s 38th annual Day of the Dead Ritual Procession will wind through the heart of the Mission on Nov. 2, before concluding at Potrero del Sol Park amid the dozens of altars, created to commemorate our dead. And while this year’s procession focuses heavily on victims of gun and police violence and those who have died while incarcerated in Trump’s concentration camps, the ritual procession in San Francisco as we know it today can trace its roots to the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s.

What has often been ignored by the mainstream media outlets and the San Francisco community at large throughout history is the absence of recognizing the gay Latino community that fell victim to homophobia and the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s.

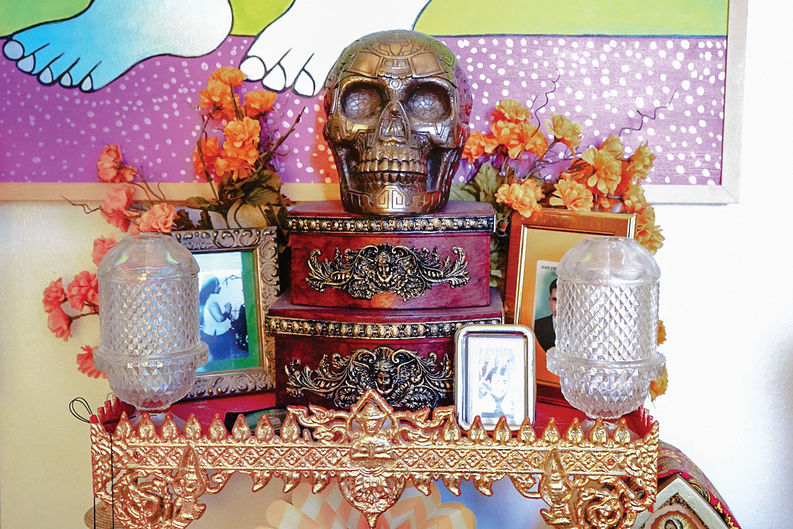

An altar sits inside the home of Juan Pablo Gutierrez on Oct. 19, 2019.

Photo: Sophia Schultz Rocha

“The minute we stepped out, the biggest fear was anyone finding out that we had HIV,” said Juan Pablo Gutierrez, a LGBTQ artist and activist who serves as director of the Colectivo Del Rescate Cultural, the entity that raises money for the ritual procession every year. “Because people still were thinking that if you shook our hands you were going to get contaminated.”

For more than three decades, Gutierrez has stood at the forefront of the ritual procession, defending it from the corporate onslaught which sought to profit from the sacred pre-Colombian holiday.

And though San Francisco did have a Day of the Dead procession before Gutierrez arrived in 1982 (it was first organized by the late co-founder of Galería de la Raza, Rene Yañez), his arrival coincided with the massive loss of life due to the dawn of AIDS.

Juan Pablo holds the 13 foot poles that were used to lead San Francisco’s 38th annual Day of the Dead Ritual Procession through the heart of the Mission on Nov. 2, 2019.

Photo: Sophia Schultz Rocha

The AIDS epidemic is one that has historically been told through the lens of the white, gay male perspective. Once in San Francisco, Gutierrez was cognizant of the homophobia and lack of education within the Latino community. It’s something he still sees today.

He believes that even now, there is no equity living in American society. There are still constant threats of attack and misrepresentation by the mainstream media that does not do justice to the Latino LGBTQ community. He remembers the fear of contracting HIV and the fears people had toward gay people during the epidemic, a lot of that fear coming from within the Latino community.

“Latino Gays, Lesbians and ‘Transgeneros,’ … do not have a voice,” said Gutierrez, “and since mainstream media sources have continued to represent the main source of knowledge and education, we recommend that they revisit the definition of the word ‘epistemology’ and practice its basic tenets, if in fact you pretend now and in the future, to print the truth.”

Photo: Sophia Schultz Rocha

The dissatisfaction and underrepresentation of the Latino gay community led to the AIDS dialogue becoming a facet of the 1984 Dia de Los Muertos Ritual Procession, which became a way for the community to speak on the disservice of the federal government toward the AIDS epidemic and ignorance to a public health crisis by the Reagan administration.

During Galería de la Raza’s Día de los Muerto’s show in 1984, Gutierrez created an altar with the words “while society turns its back, we die by the thousands and thousands and thousands.”

That call for action drew both support and backlash from the Mission community.

“The Latino community was not ready, but René Yañez, who curated the exhibition that year, took the chance in allowing us to do the installation,” Gutierrez was quoted as saying in The Heart of the Mission, Cary Cordova’s definitive history of Latino culture, art and politics in the Mission. “He got a lot of flack from various sources who wanted it removed from the exhibit, but he decided to keep it in the exhibition after a Latino couple knelt crying in front of the installation since their young teenage son had since just died of AIDS.”

The year 1984 also marked the first time the Bay Area Reporter ran an obituary on a Latino gay man, according to Cordova’s book.

New York newspapers had already been producing stories on the impact of AIDS on the gay community for a few years according to Cordova.

“Though some represented the Mission District as homophobic owing to a form of Latino conservatism, the fact is that many residents in the Mission were experiencing the brutality of this disease (AIDS) first hand,” Cordova wrote in her book.

Cordova cites the 1983 candlelight march organized by therapist Gary Walsh as one of the premiere events to raise awareness about the death toll of AIDS. Following this display of community activism would come the AIDS Quilt in 1985, the Pride Parade and Art Against AIDS in 1987.

Gutierrez adds that one of the biggest challenges of the time was the concern over how HIV and AIDS would impact the straight community.

For today, homophobia and attacks on sexuality are still very much alive. Gutierrez sees a ray of hope in the Latinx community as they become the generation to follow his in liberating sexuality and human rights.

“We’re living in a very, very challenging time,” said Gutierrez, “And it seems like that as the decades go by, things don’t get any easier. But our resolve doesn’t waver. It gets stronger. Thank God for the Latinx community because it’s now them who are picking up the torch for the next generation that’s coming in front of them.”

He also explains that the plight of the gay community is not so simple when considering the ethnography of the Latinx.

“We are 22 Spanish speaking countries that make up the Latino community of San Francisco. It’s 22 countries with their own dialects, with their own customs, with their own traditions. So to be gay, you’re talking about not just the Castro, which is the case for San Francisco, because once you leave the Castro it’s not that easy to be gay. We’re still a very homophobic city.”

When considering the stories and experiences of being gay, Gutierrez firmly believes that the intricacies of each culture is ignored.

Gutierrez and other organizers have been staunchly committed to producing the ritual procession without the financial aid of any corporations or government entities. The cost of using the park for this event is approximately $40,000. They remain vigilant to this because of their long standing motto, “Nuestros Muertos No Se Venden” (Our dead are not for sale).