Mayor Ed Lee's Police Legacy

Historical Essay

by Adriana Camarena, 2018

This article originally appeared in 48hills.com.

A hallmark of a mayor is their choice of chief of police. In 2011, Ed Lee chose Greg Suhr.

Police Chief Greg Suhr (left) and Mayor Ed Lee (right).

Suhr was an insider cop bred in the culture of the “Good Old Boys’ Club” that privileges and protects some above others, and Lee chose him despite the scandals that plagued his prior history as part of San Francisco Police Department’s command staff.

Throughout Chief Suhr’s five-year roller coaster ride in office, Lee remained aloof to problems brimming in the SFPD, unaffected after each police killing, pursuing cosmetic reform processes only when forced by circumstance. The way many of us saw it, Lee deferred to the powerful Police Officer’s Association that backed Suhr every step of the way, and that Lee never challenged.

At the peak of Suhr’s crisis as chief in early May 2016, even after a hunger strike and mass protests in the street that led to the taking of City Hall by hundreds of protesters, Lee insisted that Suhr was the reformer that the city needed, when it was clear that Suhr was there to protect the status quo.

Only when later that same month, SFPD police officers committed their 18th homicide since the start of Lee’s term in office, only then, when the mudslide of scandal carrying Suhr threatened to take Lee under as well, did the mayor accept Suhr’s resignation. Acute pressure from the community of anti-police brutality activists demanded an appropriate search for a new chief, which resulted in Lee swearing in an outsider Chief of Police William Scott in January 2017. If history proves true, outsider chiefs in San Francisco succeed with great difficulty, given that an insider is always positioned at their heels to take over at the first hint of failure.

Lee’s legacy for policing in San Francisco will be remembered as a return to a throw-back police force that San Francisco has repeatedly tried to overcome in past decades. But despite cyclical reform efforts, SFPD cannot contain the scandals that ooze out of its anachronistic, bigoted, corrupt, violent culture that is bureaucratically engrained and legally cushioned against accountability.

Chief William Scott now sits astride this hydra, playing whack-a-mole with scandals to the best of his ability, often in direct confrontation with the SFPOA. The department reform that Lee began and Chief Scott was tasked to execute is still tentative at best. The institutions in charge of checks and balances over SFPD remain incapable of meaningful action to end police misconduct. In the face of escalating crises, Lee always did too little, too late, and as a result, he harbored police impunity. That is Lee’s legacy to San Francisco policing.

It is now 2018, Ed Lee is dead, and new mayoral candidates are lining up to take his seat in the June election. [London Breed won the election to fill out Lee's remaining time, and went on to win re-election in 2019 to her own 4-year term. —ed.] Lest the candidates have forgotten the recent scandal-wracked past of SFPD under Lee, here is a walk through the most memorable incidents and damage control efforts that Lee’s police force and policing policies left in his wake. If the new mayor wants to make a difference, it will be their duty to construct a police department that serves not only the concerns of law and order of the wealthier population, but also social justice for San Francisco’s populations most vulnerable to police abuse.

Lee’s Legacy No. 1: The appointment of Chief Scandal

In 2003, Suhr, then deputy chief, was a central character in the notorious Fajitagate scandal in which top brass were charged with conspiracy to obstruct justice, after three off-duty officers were accused of beating up two men over a bag of fajitas. A judge later dismissed the charges of obstruction brought by then-District Attorney Terrence Hallinan for lack of evidence.

Following the scandal, in 2004, Heather Fong was appointed chief of police with the task to right the ship. Suhr repeatedly butted heads with her. In 2005, Suhr was removed as head of patrol by Fong, after an officer was beaten and suffered a fractured skull responding to a protest. Fong reassigned him to staff security for the city’s Public Utilities Commission.

Ironically, it was there that Suhr befriended Ed Lee, the city’s chief administrative officer at the time. Suhr again clashed with Fong when in 2009, he failed to report a boyfriend’s domestic violence against his friend. Chief Fong reprimanded him, again, and SFPD lawyer Kelly O’Haire recommended he be fired, but ultimately he was demoted to captain and served only a five-day suspension.

Chief Fong—who served from 2004-2009—only temporarily disrupted the Old Boys Club, and not without trouble, as evidenced by her struggle to command Suhr. After her resignation, she was replaced by George Gascón—an outsider who had built a 30-year career within LAPD and briefly as chief of police in Mesa, Arizona before coming to San Francisco.

It was Chief Gascón who rescued Suhr from “career Siberia” at the PUC. In 2011, electoral politics and timelines would clear the final homestretch for Suhr to grab the top cop post in San Francisco.

In January 2011, Mayor Gavin Newsom appointed Gascón as the new district attorney, after Kamala Harris vacated the position to take over as state attorney general. Ed Lee was in turn appointed interim mayor following Newsom’s election as lieutenant governor. Suhr’s nomination was backed by the SFPOA, Rose Pak and Kamala Harris to replace Interim Chief Jeff Godown.

Godown, who was a recruit of Gascón, briefly led SFPD after Gascon’s appointment to the Office of District Attorney and even more promptly exited SFPD towards Oakland on Suhr’s entrance.

On April 27, 2011, Suhr was sworn in as chief by Interim Mayor Ed Lee. In doing so, Lee willfully ushered-in a return to a time before ‘Fajitagate’ when the affiliation between SFPD leadership and that of the SFPOA was tight, white, and male. The next five years would see a sludge of corruption, racism and police impunity flowing out of SFPD.

Lee’s Legacy No. 2: SFPD officers thieving and lying on the poor

Even before Suhr had stepped into office, the mud wall of what would become his first big scandal as chief had started to cave in. Back in March 2011, the Public Defender’s Office began publishing surveillance camera videos from inside hotels housing the city’s poor that showed police carrying out warrantless searches and unprovoked uses of force. In May 2011, a new video surfaced of Officers Ricardo Guerrero, Reynaldo Vargas, Jacob Fegan, Christopher Servat and Adam Kujath carrying out an illegal search in the Julian Hotel. Guerrero is seen returning and exiting from the room of Jessie Reyes with property that was never entered into evidence. Not only did the officer steal from Reyes, false police reports were also filed against him. Taking the egregious to a new level, Guerrero was at the time the highest paid police officer in SFPD.

By November 2011, the Public Defender’s Office issued a press release noting a series of complaints filed against officers for similar incidents. The accumulating number of complaints led to a federal investigation and two grand jury indictments in February 2014. The first indictment was against Sgt. Ian Furminger, Edmond Robles, and Reynaldo Vargas in connection with selling marijuana, as well as stealing money, gift cards and computers from suspects; stealing drugs and valuables from the city. The second indictment was against Arshad Razzak, Richard Yick and Raul Eric Elias for civil rights violations connected to entering single-occupancy hotel rooms, without legal justification, and intimidating occupants and falsifying evidence to hide wrongdoing.

In 2015, spitting in the eye of public disbelief, the sentencing for Razzak was postponed so he could help SFPD carry out a training video. It was a wonder to all that SFPD chose this soon-to-be-convicted officer to make a training video.

The mudslide had begun.

Lee’s Legacy No. 3: The racist text scandals

A first series of racist texts was uncovered in March 2014, when a federal prosecutor filed a motion to oppose granting bail to former Sgt. Ian Furminger. As mentioned above, Furminger was one of the officers convicted in February 2014 in the federal corruption probe. The motion to deny his bail detailed the racist texts exchanged between Furminger and other officers. A Department investigation followed that showed that fourteen officers were implicated in the exchange of racist, homophobic and misogynist texts, including Ian Furminger, Michael Robison, Michael Celis, Rain Daugherty, Noel Schwab, Sean Doherty, Michael Wibunsin, Jason Fox, Richard Ruiz and Angel Lozano. A short selection of those texts follows:

n response to a text asking “Do you celebrate quanza [sic] at your school?” Furminger wrote: “Yeah we burn the cross on the field! Then we celebrate Whitemas.”

In response to a text saying “Niggers should be spayed,” Furminger wrote “I saw one an hour ago with 4 kids.”

“Cross burning lowers blood pressure! I did the test myself!”

“I hate to tell you this but my wife friend [sic] is over with their kids and her husband is black! If [sic] is an Attorney but should I be worried?” Furminger’s friend, an SFPD officer, responded: “Get ur pocket gun. Keep it available in case the monkey returns to his roots. Its [sic] not against the law to put an animal down.” Furminger responded, “Well said!”

In response to a text from another SFPD officer regarding the promotion of a black officer to sergeant, Furminger wrote: “Fuckin nigger.”

In April 2015, Chief Suhr moved to fire the most offending of the eight officers, but he was soon challenged in court by Rain Daugherty. In December 2015, a superior court judge ruled that he couldn’t fire them, after Daugherty successfully argued in court that Internal Affairs officers had known about the texts since 2012 and that the one year statute of limitations to bring disciplinary action under the Police Officer’s Bill of Rights had expired.

The city appealed the ruling in 2016. While we wait on the edge of our seat for news of that appeal, we can drown in the irony that SFPD could not get past the POBR when it finally set out to show a backbone in disciplining police misconduct. A few of the officers—Celis, Robison and Schwab—resigned, but Daugherty and others remain on the force.

A second series of racist and homophobic texts, reported by the SFPD in April 2016, had been uncovered as part of a Department investigation into allegations that an officer had committed a sexual assault while off-duty. The officers involved in the racist text exchanges were Jason Lai, Sgt. Curtis Liu, Keith Ybarreta, and a fourth as yet, unidentified officer.

“I hate that beaner, but I think the nig is worse,” read one text.

“Indian ppl are disgusting,” stated another.

“Burn down walgreens and kill the bums,” went a third message.

Lai also referred to a police sergeant as a “passive aggressive 528,” using the code for a fire call as a way to describe gay officers as “flames or flaming.”

In May 2016, by now in damage control mode, the department again revealed that yet another member, Sgt. Lawrence Kempinski, who worked out of Bayview was being internally investigated for making racist and sexist remarks. A clarification was soon issued regarding what he had actually stated. To nobody’s relief, Kempinski had not said that “he only transferred to the station to ‘kill n—-rs’, but that he had come to the station to “chase Negro boys around.” He also insulted a female worker, who inquiring whether he was wearing his gun, let her know, “I got a big gun for you.”

The problem though was not just what the officers had written or said, but the deeper implication that police culture remains embedded in the mindset of the Good Old Boys’ Club. Police work was bound to be skewed by bigotry against people of color, women, the LGBTQ community and vulnerable members of society such as the homeless and mentally ill.

Lee’s Legacy No. 4: Officers racially profile and oppress black San Franciscans

Under Lee, black youth in San Francisco were repeatedly criminalized by police for exercising their most basic civil rights, such as socializing and bicycling, with little to no consequence for the officers involved.

In October 2011, two officers—Joshua Fry and John Norment—walked up to a group of young adults on Mendell Plaza in the Bayview and disconnected their boom box. The action was perceived as an assault on the community life that gathered on a daily basis at that spot. Officer Fry and Norment began filming the riled-up crowd with their cell phones, and in response, rapper Fly Benzo (DeBray Carpenter) recorded them as well. In the face of vocal dissent, Ofc. Norment shook his pepper spray, escalating the situation further. Benzo continued to film. Ofc. Fry grabbed and twisted Benzo’s arm while other officers closed in and forced him to the ground. Fly Benzo—a straight-A City College student, a community organizer who had spoken out prominently after the shooting of Kenneth Harding Jr. a block away in the Bayview in the summer—was arrested and eventually convicted of three misdemeanor counts of resisting arrest, assault upon a police officer, and interfering with officer duties.

Zero lessons were learned by police officers from the Fly Benzo incident about how not to racially profile and antagonize youth of color. If anything, the Benzo case proved that officers would face no accountability for behaving in this manner.

In May 2015 a group of young rappers— Yung Lott (Arthur Stern, Jr.), Joeski (Joseph McGowan), Dante Andry, Brian Storm (Brian MacArthur) and about 15 other young black men—had gathered at a Hunters Point playground to film a rap video with the intent of uniting local rap artists. Suddenly they were surrounded and forced to the ground by a near equal number of uniformed and plainclothes police officers. For the next two hours, officers questioned, photographed, and confiscated the possessions of each person. Lott, Joeski and Andry filed a lawsuit that detailed the events of the day. The officers justified themselves claiming they saw an individual with a gun but the lawsuit alleged that individual was not part of the group.

There were also individual incidents towards Black men. In January 2013, a four-minute video captured an unidentified motorcycle cop riding his bike on the sidewalk near the 24th Street BART station. He gets off, grabs Kevin Clark, who was 18 at the time, slamming him to the ground. A companion officer joins him to pin the teenager at the intersection, his face against a sewage grate. Apparently, Clark had wanted none of the officers’ attention and was rapidly walking away, which was the only provocation the officers needed.

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/UDBq70mfIpQ" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Lorenzo Adamson, a Black SFPD officer, accused three white SFPD officers of racially profiling him following a traffic stop in the Bayview neighborhood of San Francisco while he was off duty. Despite telling them that he was an officer, the traffic stop resulted in a physical confrontation and arrest. The incident happened in June 2013.

In November 2013, D’Paris “D.J.” Williams, 20 at the time, a Black City College student, rolled onto the sidewalk on his bike to the entrance of the Valencia Gardens housing complex where he lived. Three SFPD Officers— Gregory Skaug, Milen Banegas and Theodore Polovina —tried to stop him. Williams carried on and went home. The officers went to his house, grabbed him, and beat him unconscious. The incident was partially caught on cellphone video and went viral. Williams filed a lawsuit and settled in July 2015.

In January 2015, Officer Carrasco was filmed trying to shove a black quadriplegic man, Devaughn (Bo) Frierson, out of his wheelchair. Frierson is a community activist who was objecting to an arrest being carried out by Carrasco. Ofc. Carrasco justified his use of force saying Frierson had run over his foot, even though that doesn’t seem to happen on the video.

In April 2015, legal documents state, Travis Hall, a black 23-year-old San Francisco graphic designer and a recent Fordham University graduate, was detained, beaten and arrested by SFPD officers as he exited a car and tried to walk home. With the help of the ACLU he filed suit.

That same month of April 2015, news broke that Operation Safe School—a 2013 joint sting between SFPD and the DEA to investigate drug dealers in the Tenderloin—was falling completely apart after it was shown that all 37 of the “suspects” targeted, rounded up and indicted were Black, that officers showed racial bias in the investigation leading up to the sting, that they deliberately threw a blind eye towards a non-black suspect, and used racial slurs during the operation. Operation Safe School was a perfect example of how SFPD operated, in general, in a city were less than six percent of San Francisco residents are Black, but more than 50 percent of people arrested and in jail are Black and 60 percent of children in juvenile detention are black.

Lee’s Legacy No. 5: The epidemic of killings of Latinos and Blacks by SFPD officers

While the racist texts and racial profiling scandals of the period provided context of how SFPD operated, officer involved shootings in this period backed the community perception that brutal use of force by SFPD had escalated, especially against blacks and Latinos.

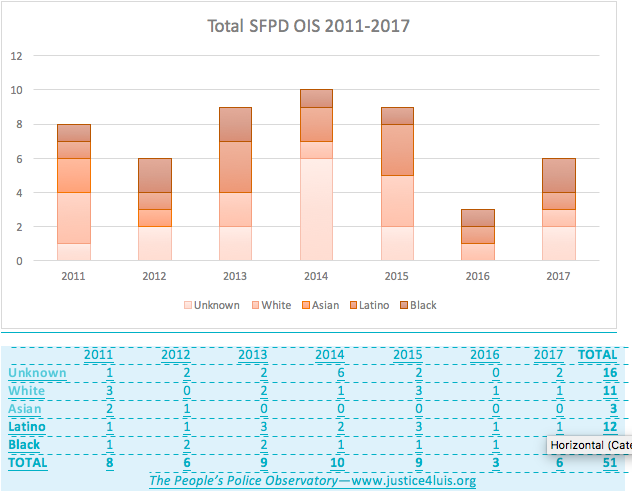

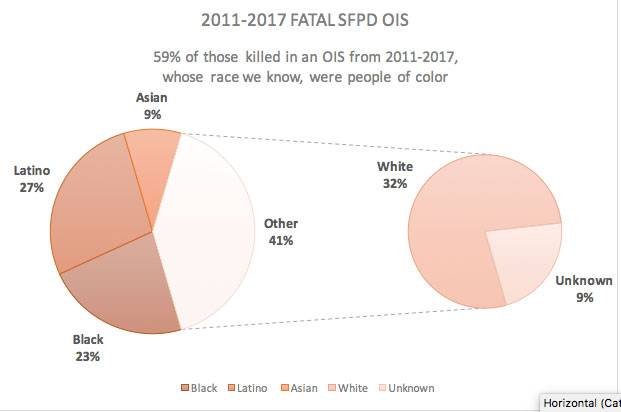

In 2014, the SF Weekly reported that based on available data for 2011, San Francisco was the deadliest city in the United States that year based on cop killings per capita, beating out New York which has ten times the population. The SF Weekly also reported that 2011 was the bloodiest OIS year on record in San Francisco since 1990. Without reliable comparable data, it is hard to say whether SFPD maintained its countrywide lead on killings per capita, but 2014 outnumbered the OIS on record for 2011 with 10 shootings that year. For the period, January 2011 to December 2017, there were a total of 51 SFPD OIS. That was nearly 8.5 OIS on average per year. Of those OIS, 43 percent were fatal.

Latino and Black residents were also disproportionately represented in OIS. Based on known ethnicity and race, 49 percent of OIS involved people of color; and 59 percent of fatal OIS were of people of color. Based on City demographics, Black people are 5 times more likely to be shot and killed by SFPD than white people in the City; and Latinos in San Francisco 2.4 times. The trend of killing people of color was particularly acute in the two-year period between 2014 and 2016, when nine out of the 12 people killed by police were Latino and Black.

The killings of people of color by San Francisco police took place in the midst of revelations of the racist, misogynist and homophobic culture of the department.

On the heels of the first racist text scandal, Alex Nieto, a 28 year old Chicano City College student and nighttime security guard, would be killed by police on March 21, 2014, in a hail of 59 bullets in Bernal Heights Park.

Solidarity march demanding justice for Alex Nieto leaves from the site of his police murder on Bernal Heights, August 22, 2014.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The justification given by Chief Greg Suhr at a rowdy Town Hall meeting was that Nieto had willfully threatened officers with a Taser. Nieto was a lifelong Mission Latino community member and many who knew him immediately rejected the characterization given of him by police.

It was also soon revealed that the dispatcher had portrayed Nieto to responding officers in such a manner that profiled him as a gangbanger. Officers surrounded the hill ready for battle, despite the fact that the only act described by the 911 caller was that Nieto was eating near a bench. The public immediately suspected that the 911 caller was a techie newcomer to the area, who feared the sight of a local homeboy.

That fact proved true during the civil trial in March 2016 two years later. The jury sided with SFPD officers, calling their actions lawful.

The trial however provided astonishing details that raised questions about how the crime scene was managed and whether the District Attorney’s Office had manipulated the data on the Taser that was reported to be holstered on Nieto’s hip.

The most galling evidence however was the incredulous tale told by the four officers who killed him, as to why they unloaded, reloaded, and unloaded their firearm at Alex Nieto. The officers portrayed Nieto as a scary super-human who was able to withstand 14 bullet impacts (which caused various fatal wounds) to the face, chest, leg and spine, all the while brandishing a Taser at them. The officers said they were forced to keep shooting until the 59th bullet was expended.

The Mission community understanding of the Nieto civil trial evidence was very different. Many of us left with the distinct impression that the first responding rookie cop Richard Schiff and his supervising Sgt. Jason Sawyer had started an unprovoked one-sided gunfight with a young man sporting his favorite 49ers team jacket, while eating a silver-wrapped burrito.

In February 2015, another scandalous OIS took place in the Mission District, this time involving a Guatemalan Mayan youth, Amilcar Perez Lopez, 21. Mission Latinos felt besieged by police in their gentrifying neighborhood. At the Town Hall meeting that followed, Chief Greg Suhr portrayed Amilcar Perez Lopez as a homicidal maniac lunging with a knife at officers. Community activists provided alternative witness narratives that said he was running away from them. In April, a press conference was held by Amilcar’s family and their civil lawyer, revealing the results of an independent autopsy that showed Amilcar was shot six times to the back. Chief Suhr was forced to realign the officers’ script to explain how Amilcar could simultaneously be lunging and moving away from them.

February 26, 2015, Amilcar Perez-Lopez lies dead between parked cars where a cop is over him, as police hold his antagonist at upper right, while at lower left two police urgently discuss their story.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

In April 2017, the District Attorney George Gascón declined to press charges, stating that there was insufficient evidence to prove unlawful actions. In January 2018, his parents—humble indigenous peasants in rural Guatemala—quietly settled the civil case.

Mayor Lee was undoubtedly in the know that SFPD officers were disproportionately killing Latino and Black city residents, and yet he took no steps to curb the violence.

On December 2, 2015, Mario Woods was killed in a blizzard of bullets, pinned against a wall, surrounded by a gang of five SFPD officers: Charles August, Nicholas Cuevas, Antonio Santos, Winson Seto and Scott Phillips. His unjustifiable death was caught on at least three cellphone videos. Once again officers claimed Mario Woods had threatened their lives, which was clearly not the case for a common-sensed citizen observer of those videos. The African-American community in the Bay View rose up strongly, alongside the Latino and faith-based communities of the Mission, who had already been rallying for justice for Alex Nieto and Amilcar Perez Lopez.

During that traumatic period of 2014 to 2016, with every killing by SFPD officers, community trauma increased, outrage rose, and with it, a demand for an independent federal investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice into the killings. In the case of Mike Brown in Fergusson in 2014, it became clear that when the population raised the political stakes high enough, the FBI and DOJ would fly over to investigate. Three common demands were made by the coalitions for justice for these young men of color in San Francisco:

• An independent DOJ investigation into the killings,

• Charge the killer cops, and

• Fire Chief of Police Greg Suhr.

The mudslide was swelling.

Lee’s Legacy No. 6: Police abuse of the homeless

The illegal hotel searches by Furminger and others showed us a set of cops who victimized poor residents that they thought too vulnerable to complain. Under Lee, inequality was skyrocketing in the midst of a dire housing shortage for low-income and impoverished populations. Both the wealth inequality and the housing shortage were a direct consequence of Lee’s policies that included brokering tax incentives for tech companies, authorizing privatized shuttle services to Silicon Valley, and rubber stamping real estate development deals to benefit the wealthy.

As the rift between the extremely rich and extremely poor widened, police were called in to solve the aesthetically cumbersome problem of visible poverty on the streets. While the homeless population of San Francisco has remained stable in the last years, street encampments have grown visibly and 311 complaints about homeless people have quintupled. 311 calls often then lead to 911 calls and inevitable police involvement.

SFPD officers have a unique ability to escalate almost every street encounter with tough talk and manhandling, making them alarmingly ill equipped to interact with the homeless, many who suffer disabilities, including mental illness.

Almost forgotten now is the non-fatal shooting of Randal Phillip Dunklin, on January 4, 2011. Dunklin was then 55 years old, wheelchair bound and homeless. Dunklin was upset that he was denied services at the Community Behavioral Health Services on Howard Street. He acted out, slashing tires on nearby cars. The police were called in to attend to the mentally ill man. Dunklin was in his wheelchair during the entire encounter with police.

In a fast escalating sequence of events, officers surrounded Dunklin. He was then pepper sprayed by Ofc. Terence Saw and shot with an Extended Range Impact Weapon (ERIW, e.g. bean bag rifle) by Ofc. Courtney Smith. Angered, Dunklin aimlessly threw the knife in his hand. Ofcs. Terence Saw and Noah Mallinger retaliated by each shooting him once with a live round.

The shooting was caught on a cellphone video. Dunklin was criminally charged with stabbing an officer, felony assault, and resisting arrest of which he was ultimately acquitted by a jury. The officers claimed fear for their lives and faced no consequence.

In July 2014, a young homeless man, Joshua Boling, then 22, walked away from officers who approached him on a bench in the Panhandle area of Golden Gate Park. He did not want to interact with them and simply walked away. He was pursued by six to ten officers, including James Tacchini, Joan Cronin, Michael Diskin and Elizabeth Prillinger, who proceeded to beat and arrest him without cause. Boling was charged with eight felony counts. A jury found him not guilty in October 2014.

The incidents of abuse of the homeless population, unfortunately, go on. In February 2015, Ofc. Raymond Chu was called to remove a sleeping homeless man, Bernard Warren, from a Muni bus. Caught on Muni and surveillance cameras, Chu rapidly escalated to brutal use of force to remove Warren, shoving him off the bus, hitting him five times with a police baton, and pepper spraying him. Chu then arrested Warren and booked him on charges of threatening an officer.

In August 2015, officers stopped a 42-year-old black man in the Mid-Market area, because he was carrying his crutches in his hands. Fourteen officers gathered around him, while at least four of them crushed him with their weight on the ground, stepping on his prosthetic leg in the process, and pressing his face against dirty ground. The incident was caught by bystander video and went viral. The officers justified themselves saying that this was a wellness stop of the man.

The abuse towards the homeless peaked on April 7, 2016, when two SFPD officers, Michael Mellone and Nate Steger rushed a homeless man in the Mission District and shot him to death in less than 30 seconds. Luis Góngora Pat was a Mexican Mayan man, 45 years of age, living at the time in an encampment on Shotwell Street.

Two-week vigil in April 2018 demanding the District Attorney George Gascón file criminal charges against the police who murdered Luis Góngora Pat.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The two officers arrived following a call about a man with a knife placed by a female member of the SF Homeless Outreach Team. By all eyewitness accounts, Góngora Pat was sitting on the ground, minding his own business when the officers arrived. A surveillance camera partially caught the shooting, which shows how within 28 seconds of exiting their patrol car, the officers shot five ERIW rounds (less-fatal bean bags) overlapping with seven live rounds. The autopsy showed that all the initial ERIW rounds had hit Góngora Pat in the back. Eye witnesses say that he got up startled and partially propelled by the bean bag rounds, only to fall back down immediately wounded by gunshots. Góngora Pat’s body showed a straight downward trajectory shot to his temple, indicating that he had already fallen wounded when officers chose to fire a final execution shot.

After the shooting of Luis Góngora Pat, five lifelong Latino and Black residents of the City, spontaneously started a hunger strike which lasted 17 days. They became known as the Frisco 5. At a peak moment during the hunger strike, a massive march took the Frisco 5 in wheelchairs to City Hall to the raging demand of “Fire Chief Suhr!” The day after the hunger strike ended, in early May 2016, hundreds of community members stormed City Hall, resulting in the arrest of 33 protesters. This uprising came to be known as the Frisco 500.

Ensconced in a bubble of self-satisfied hubris, the mayor announced in the days that followed that the City would pursue police reform! And that he had just the right man to see it through: Chief Greg Suhr!

Days later, on May 19th, Jessica Williams, a young black and homeless woman, four-months pregnant, was shot to death by Sgt. Justin Erb, while she was sitting in a stolen car.

The mudslide had finally overtaken Chief Greg Suhr and he resigned.

Lee’s Legacy No. 7: Assessments and more assessments to distract from police impunity

The slew of killings and excessive use of force by SFPD officers; their racist, homophobic and misogynist texts; the acts of corruption; the false police reporting (i.e. lying); and other SFPD scandals that included cases of favoritism in the Department and sexually predatory behavior by officers will be the mark of Lee’s police department. But because Lee did nothing of significance to seek accountability for the mounting abuses, he will be remembered most for encouraging police impunity.

District Attorney Gascón, throughout his initial appointment and then elected term in office, has failed to file criminal charges in cases of officer misconduct, including officer involved shootings. If anything, Gascón has showed that he will pursue charges against people who claim police abuse.

He pressed criminal charges against Randal Phillip Dunklin, Joshua Boling, Fly Benzo (DeBray Carpenter), Joel Henriquez, and Charles Tran and others claiming police misconduct.

Lee never challenged Gascón. More importantly, when Lee was given a clear chance at calling for a federal investigation into the killings, he willfully ditched this option in favor of a federal assessment of SFPD.

On January 26, 2016, in the face of clear community demands, the Board of Supervisors issued a resolution requesting the U.S. Department of Justice carry out an independent investigation into the killings of Mario Woods, Alex Nieto and Amilcar Perez Lopez. In response, the mayor favored a duplicitous interpretation and work around to the BOS resolution.

In February 2016, the Mayor entered into an agreement with the Office of Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) of the DOJ called the Collaborative Reform Initiative for Technical Assistance. The objective was to assess SFPD against contemporary standards of policing and recommend reforms. By calling upon the COPS division, the Mayor skirted the Civil Rights Division of the DOJ, which has the actual power to investigate civil rights violations such as extrajudicial executions by police.

Come fall 2016, the ills of SFPD would be thoroughly diagnosed. Under the Reform Initiative, COPS carried out an assessment of SFPD, which report was issued in October 2016 providing 272 recommendations across thematic areas of Use of Force, Bias, Community Policing Practices, Internal Discipline, Hiring and Personnel, Accountability, and Departmental Orders and Bulletins. The COPS assessment was based on the recommendations of President [Obama]’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing.

The task force was a one-of-a-kind effort to provide guidance on how police departments could enter this century after a legacy of harm to people of color. Previously, in September 2015, the Office of Citizen Complaints —later to be renamed the Department of Police Accountability — had already issued recommendations to SFPD based on the same report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing.

In 2015, Gascón tepidly responded to the scandals by convening a Blue Ribbon Panel on Transparency, Accountability and Fairness in Law Enforcement. A year later, in July 2016, the independent Blue Ribbon Panel issued the scathing results of its investigation into SFPD. Although Gascón gained a media reputation as a progressive prosecutor for convening the Blue Ribbon Panel, he has continued to decline to press charges against any officer involved in shooting, while pursuing charges against victims of excessive use of force by police.

In the same period, a Civil Grand Jury investigated various San Francisco officers, departments and agencies and issued five reports between June and July 2016, with a total of 52 recommendations for SFPD on auto-burglary, the scandal battered SFPD crime lab, homeless health and housing, OIS, and the SF jail. The Bar Association of San Francisco’s Criminal Justice Task Force also jumped on the diagnostic bandwagon by issuing a report and recommendations on data collection and analysis in August 2016.

Problems that had been historically pointed out by communities impacted by police misconduct were now documented in official reports by the COPS-DOJ, a Civil Grand Jury and the DPA, as well as by independent studies of the Blue Ribbon Panel and BASF. The assessments provided a public indictment of police misconduct, and SFPD accepted them as the basis for structuring a reform process. These reports can be accessed on SFPD’s reform initiative page.

Unfortunately, the families and communities demanding justice for Alex Nieto, O’Shaine Evans, Amilcar Perez Lopez, Mario Woods, Luis Góngora Pat, Jessica Williams and many others killed by police under questionable circumstances were no closer to seeing an independent investigation into the killings or a meaningful act of justice. The assessments and public denouncements were so much smoke and mirrors for ongoing police impunity.

Lee’s Legacy No. 8: An outsider Chief of Reform pitted against the SFPOA

After the resignation of Chief Suhr, community members poured their attention towards the closed-door nomination process in the Police Commission for the next chief of police. Through presence and persistence, activists made plain that only an outside candidate would be acceptable. The next chief would need to break away from the Old Boy’s Club backed by the SFPOA. Despite Ed Lee’s initial favoritism for the interim Chief of Police Toney Chaplin, in January 2017 he swore in William Scott as the new chief of police. This would be Ed Lee’s most dramatic nod to change.

The SFPOA lost no time in creating internal strife for the outsider chief. The president of the SFPOA, Martin Halloran, sent an email just hours after the announcement of Lee’s pick, informing members in the union that the Mayor had “turned his back on the rank and file police officers.” Nevertheless, William Scott, an African American, hailed as a reformer, who had previously risen to the rank of deputy chief of the South Bureau of Los Angeles Police Department, became chief of police of San Francisco on the promise of change.

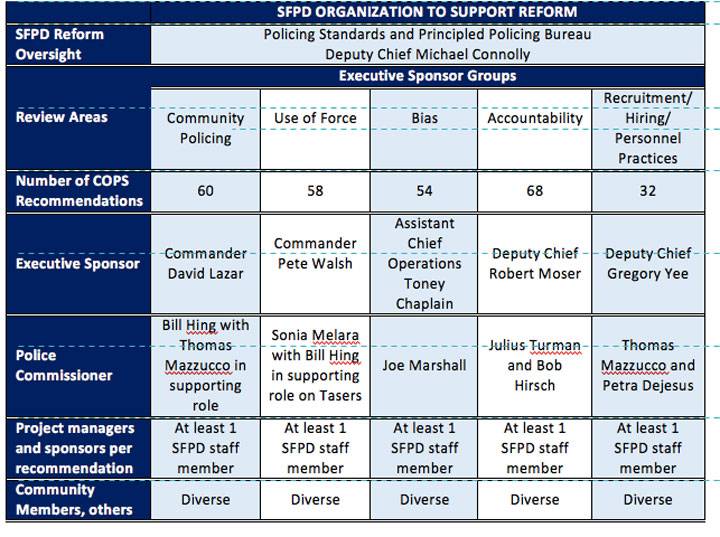

Under Chief Scott the timetable of the COPS Reform Initiative was reassessed, and an entire organizational structure was created within SFPD to support the reform process. In February 2016, when the Reform Initiative was originally entered into, the Professional Standards and Principled Policing Bureau of SFPD was created to coordinate the reform efforts. Michael Connolly was assigned as head of the PSPP, in charge of tracking the various moving parts of the assessment and reform process.

In this regard, the PSPP is the closest that SFPD has to a “strategic planning department.” Notably, Connolly lacks any experience in reform processes or strategic planning. He was, however, involved in three OIS in 1992, 1994 and 1995, which apparently qualifies a person to lead reform process, since in July 2016, Nate Steger, one of the killers of Luis Góngora Pat was also appointed to the PSPP. Steger was quickly removed after community activists caught wind of the appointment.

A year later, in February 2017, the newly sworn-in Chief Scott promoted a bulky command structure under the argument that a broader leadership structure was necessary to ensure the implementation of the Reform Initiative. In layperson terms, the chief needed a greater number of command officers with the legal authority to order their subordinates into collaborating with the reform. It also seemed a wise move for an outsider chief to promote officers from within.

In January, the position of Assistant Chief had been created and interim Chief of Police Toney Chaplain and Hector Sainez were promoted as such. A month later, Robert Moser was promoted to deputy chief, Michael Connolly to deputy chief, David Lazar to commander, Peter Walsh to commander, Daniel Perea (former captain of the Mission Police Station) to commander, and Gregory Yee to commander.

The top leadership of the department now consists of one chief of police, two assistant chiefs, five deputy chiefs, eight commanders, three directors and 24 captains, which as reported in the SF Weekly, will cost the city a total of more than $10 million in salaries a year.

The sole woman on the command staff prior to the promotions— Deputy Chief Denise Schmitt—also the most senior ranking officer at the time and a LGBTQ community member, was reassigned to the Airport Bureau, which is considered career block within SFPD.

The SFPOA again lost not a minute to flex its muscle against Chief Scott, this time under a progressive veil that called for greater equality in the ranks. The SFPOA conveniently ignored that all the men that were promoted had come to prominence under Chief Greg Suhr, their guy. Sgt. Yulanda Williams, head of Officers for Justice, a union in support of racial minorities, also called out the hypocrisy of the SFPOA. Williams had been attacked in the racist texts, and had also resigned from the SFPOA for their lack of support for minorities. Pointedly she noted the SFPOA’s own lack of diversity: Of the 32 members of the POA Board of Directors, only two are female, and the entire elected executive board consists of men.

Substantial public institutional reforms are never smooth, primarily because they shake up the bureaucratic status quo. Unsurprisingly, Chief Scott seems to have spent a good portion of his first year in office in a political fight with the SFPOA that is unfolding among the rank and file officers. In September 2017, the chief announced the promotion of seven African-American officers, men and women, raising the number of black officers in positions of leadership to 19, a record in SFPD since its founding in 1849.

A month later, in November, the chief announced that by July 2018, after the renovation of the SFPOA contract in June, the command staff of SFPD will no longer be members of the SFPOA. The chief pointed out the obvious conflict of interest that exists when management level staff and subordinate staff belong to the same union. For purposes of this change, command staff was defined as positions above captain. Command staff will instead remain members of the Management Executive Association.

The various assessment reports of 2016 pointed out a toxic work environment at SFPD. Fingers were specifically pointed at the SFPOA for being complicit in maintaining an “Old White Boy’s Culture.” Among reform efforts, Chief Scott seems most intent in combatting racism, sexism and favoritism in recruiting, hiring and personnel practices in SFPD.

Lee’s Legacy No. 9: An SFPD reform initiative, disconnected from community priorities

While Chief Scott settled his house, the rest of the reform process suffered from a lack of depth and coherency. With key exceptions, the Reform Initiative in SFPD has been orderly, but lacks transparency and accountability. There is no guarantee that the process will resolve the ailments so thoroughly diagnosed for SFPD.

Under the Reform Initiative, five Executive Sponsor Working Groups were created corresponding to the five thematic review areas of reform (Community Policing, Use of Force, Bias, Accountability, and Recruiting, Hiring and Personnel Practices). From within the new command group created by the new Chief, Chief Scott assigned an Executive Sponsor to each ESWG. Additional officers may also be assigned as project managers for specific recommendations. Participation in the ESWG is furthermore an additional task to an officer’s regular employment. During Spring 2017, the President of the Police Commission also assigned each of the seven commissioners to participate in each ESWGs. On the invitation of the Executive Sponsors, additional community members participate on a voluntary basis on the ESWGs.

The Executive Sponsor of each group manages the meeting. A group of officers assigned to the ESWG supports its logistics. Officers of the PSPP and the Community Engagement Division also provide logistical support across ESWGs. During each working session a number of recommendations are presented. Each recommendation is presented by the Project Manager or individual Sponsor in charge of seeing through its implementation. Presentations tend to be brief and are followed by an open discussion and exchange between presenters and community members involving questions, answers and comments.

Based on the feedback received, the Executive Sponsor provides the Chief a recommendation on how to implement each of the COP recommendations. The chief then makes a final decision about how to implement the recommendation. The Policing Standards and Principled Policing Bureau tracks how each COPS Recommendation will be implemented. Until recently, the PSPP acted as the counterpart to the COPS, reporting back to the COPS office how each COPS Recommendation would be fulfilled for approval by way of a quality control by the COPS. Once approved by the COPS, the Department would proceed to implement the approved activity related to that COPS Recommendation.

In September 2017, Jeff Sessions, the new head of the Department of Justice, abruptly ended all support from COPS to reform initiatives across the country, in favor of a hardline approach to combatting crime. Decades-long research has shown that a hardline to combatting crime does not improve public safety, but only increases criminalization of people of color. Despite the end of the COPS Reform Initiative, Chief Scott has explicitly committed to seeing through the implementation of the Reform Initiative and in February of this year, SFPD agreed that the State General Attorney Xavier Becerra should step into the role vacated by the DOJ.

But issues have arisen related to decision-making in the ESWG. The Executive Sponsors are not obliged to accept the community commentary. The Executive Sponsor makes the ultimate decision about what he will recommend to the chief. The chief and the command structure of SFPD might feel that this consultative but undemocratic process is normal, but for community participants at the table, it has led to a lack of transparency and accountability.

In other words, throughout 2017, participating community members (the author included) provided feedback on various COPS recommendations under review, but there was no transparency from the Executive Sponsors as to what they actually understood or recommended to Chief Scott for approval. Next, there was no understanding of what Chief Scott actually approved for implementation. More critically, there was no way of knowing how the chief was prioritizing the 272 COPS reform recommendations to meet the overriding concerns that led to reform in the first place.

The Taser debacle of 2017 revealed the weakness of the reform process.

The SFPOA and the SFPD have been pushing to acquire Tasers since at least 2004, failing each previous time after community push-back. The issue of Taser approval was raised again because one out of the 58 recommendations made by the COPS on Use of Force suggests that SFPD “consider” acquiring Tasers. Under the Reform Initiative, the Executive Sponsor Work Group on Use of Force took on the challenge of asking for community input on Tasers. The ESWG collapsed into a straight-out confrontation between community members against Tasers and Police Commissioner Sonya Melara staunchly in favor. Melara was appointed to the Police Commission by Mayor Ed Lee in 2014.

To the dismay of activists combatting police brutality, Chief Scott backed the acquisition of yet another deadly weapon for SFPD. Despite vociferous community rejection of Tasers in the ESWG and at Police Commission meetings, the Commission took up their approval last November. The meeting lasted seven hours and resulted in a closed-door vote after protesters were shut out. The Police Commission has yet to approve a policy for the use of the Tasers, but the chief hopes to have officers sporting their new weapon by December 2018. The cost of buying Tasers for SFPD is estimated at $8 million dollars.

In the case of Tasers, the reform process was itself used to counter community demands. The vast majority of the COPS Use of Force recommendations focus on improving investigations, improving data collection, and increasing transparency in use of force incidents, as well as promoting crisis intervention training and tactics. Instead, the long standing SFPOA demand for Tasers took priority.

Backing Tasers damaged the reputation of Scott as a reformer, but also put a spotlight on structural problems with the reform process. While the Reform Initiative has been inclusive of community feedback, SFPD decision-making about reform priorities is mired in a lack of transparency and accountability.

The SFPOA is now actively campaigning to win approval of its own Taser measure on the June election ballot to avoid a reversal of approval [This measure was defeated in the 2018 election 60-40]. Over this, tensions between Chief Scott and the SFPOA have flared up again, with the former standing staunchly against a ballot measure, arguing it would impede the Police Commission from issuing a policy that could be adjusted more practically over time. The ongoing battle over Taser policy is further proof of how much this decision was outside community priorities and internal to cop politics.

For all its $10 million a year command structure, the Reform Initiative leaves us all wondering how SFPD will show measurable progress towards reducing bigotry, raising transparency, ending police brutality and impunity, and overall changing its culture.

Moreover, the Reform Initiative is embedded in the concept of community policing that supports, among other things, a reorganization of SFPD as an agency that is open and responsive to continual community input into problem solving. That particular understanding of Community Policing is nowhere close to being implemented.

Without consulting the Community Policing ESWG, the chief has moved to increase police presence in neighborhoods such as the Mission, Bayview and Tenderloin that historically house the city’s Black and Latino residents and historically have been site to the greatest number of OIS and other notorious incidents of police racial profiling and brutality. By September 2017, the chief had quadrupled foot patrols in the Mission to address concerns for car break-ins, but the most measurable change in the Mission was a 13 percent rise in police Use of Force incidents reported for the third quarter of 2017.

Despite the Reform Initiative, it seems that the more things change, the more things stay the same. OIS climbed again in 2017 after taking a noticeable dip during 2016. Two OIS in particular—the non-fatal shooting of mentally ill Sean Moore on January 6, 2017 and the fatal shooting of Keita O’Neil on December 1, 2017, both men of color—gained community attention. In the OIS of Sean Moore, D.A. Gascón was quick to press charges against Moore for assault on a peace officer, battery on a peace officer, resisting arrest, criminal threats and contempt of a court order. But when the officer bodycam video of the incident was published by Public Defender Adachi, it became clear that the officers had goaded Sean Moore into a physical confrontation, in part by unlawfully trespassing onto his property in order to unlawfully restrain him and shoot him. Charges were dropped against Moore.

In December 2017, Keita O’Neil was killed while fleeing from a stolen vehicle. He was unarmed, but rookie cop Christopher Samayoa still shot him in the head as he ran by. Samayoa shot through a closed passenger window, while sitting in his patrol car.

Lee’s Legacy No. 10: Inane administrative checks and balance on police impunity

Mayor Ed Lee inherited a problem about which he never did anything about. Namely, the city’s disciplinary and investigative agencies of police misconduct: The Police Commission and the Department of Police Accountability.

The Police Commission of San Francisco has existed since 1878 as an oversight and policy agency of SFPD. From 1900 onward, the mayor was responsible for appointing the commissioners. In 2003, following the ‘Fajitagate’ scandal, the number of commissioners was increased from five to seven, of which the mayor appoints four and the Board of Supervisors three. Commissioners are appointed for four-year terms, which can be renewed. Since then, it has become habit that the mayor appoints conservative members to the Police Commission and the Board of Supervisors struggles to appoint progressive members.

Of the seats that opened up during his term in office, Mayor Ed Lee appointed Suzy Loftus, in 2012 and Sonia Melara in 2014. Joseph Marshall, originally appointed by Gavin Newsom in 2004, was appointed to his fourth term by Lee in 2014, and Thomas Mazzucco, originally appointed by Gavin Newsom in 2007, was appointed to his third term by Lee in 2016. Robert Hirsch, was appointed by Lee in 2017, after Loftus resigned.

Mayoral appointees are notorious for toeing the line of the Mayor, and by association, that of the SFPOA. Predictably, when the Taser vote came up last November, Melara, Mazzucco, Marshall and Hirsch gave the majority approval on the contentious vote.

The Police Commission does not often pursue meaningful progressive policy changes. Only after the killing of Mario Wood, at the peak of the SFPD scandals, and only because the mayor requested it, did the Police Commission review SFPD’s use of force policy.

The Use of Force policy had not changed since 1995. Community members pushed hard for a new Use of Force policy that aimed to preserve the principle of sanctity of life by making de-escalation mandatory. The new Use of Force policy approved in 2016 instead limited changes to prohibiting officers from using the carotid restraint and shooting at moving cars.

Given that carotid restraints often lead to choking people to death, and that at least eleven OIS in San Francisco since 2011 have involved shooting at people in cars, the change was an improvement. The Use of Force policy also noted that officers would not be found negligent if they used de-escalation as an option. This has opened, albeit belatedly until midway through 2017, an increase in training in de-escalation tactics. However, de-escalation is not mandatory, and the commissioners maintained the policy that allows officers to use deadly force based on the mere perception of threat to their lives or serious bodily injury. In other words, the very rule at the heart of police impunity for excessive use of force remains on the books.

Until the killing of Alex Nieto in 2014, the Police Commission would also unthinkingly award officers involved in any fatal shooting, a medal of valor.

The Police Commission oversees the Department of Police Accountability (until 2016 known as the Office of Citizen Complaints, OCC). The OCC was created in 1983 by a ballot measure to investigate allegations of police misconduct made by members of the public. The idea behind the OCC was that citizens could have a say in increasing police accountability, by filing complaints, complaints would lead to investigations, which would lead to findings, and findings to disciplinary consequences. The problem though was that the OCC acts like a paper tiger, basing its investigations primarily on SFPD incident police reports and officer testimony, which skews investigations against finding in favor of the complainant.

Two ballot measures were introduced by the Board of Supervisors in 2016. Proposition H which aimed to create an Office of Public Advocate that would act as an autonomous investigative body into public officer misconduct. The Public Advocate would absorb the OCC. The other Proposition G, which would change the name of the OCC to the DPA and allow the DPA to pursue investigations rather than wait for a complaint to trigger the investigative process. Mayor Ed Lee opposed Prop H. The SFPOA also lobbied against the creation of an autonomous investigative body, running ads that implied that the Office of the Public Advocate was only a new job position sought by Supervisor David Campos. Voters chose to change the name of the paper tiger, and not increase its investigative autonomy.

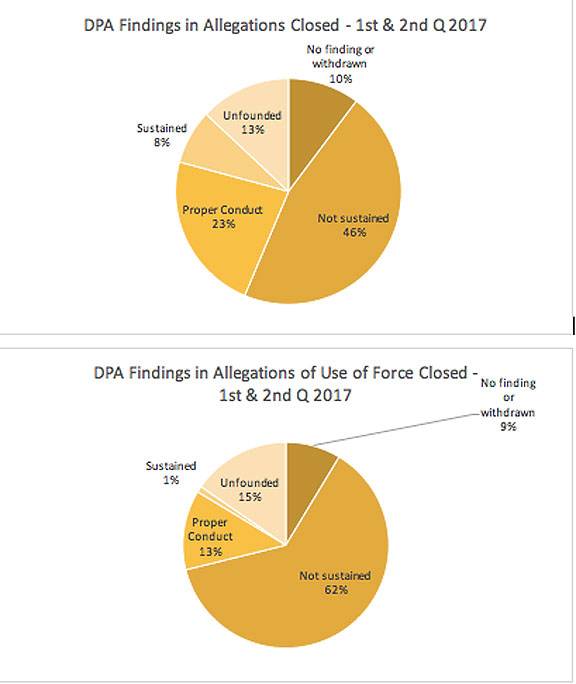

There is no indication that the DPA and the Police Commission have any significant effect on police accountability. Based on available statistics for the first and second quarters of 2017, the DPA closed 1,015 allegations across categories of Unnecessary Force, Unwarranted Action, Conduct Reflecting Discredit, Neglect of Duty, Racial Slur, Sexist Slur, Discourtesy, Procedure, Policy and Training Failure. Of these, only 8% of allegations of misconduct were sustained by the DPA. Of all allegations of Unnecessary Force closed by the DPA during the first and second quarter of 2017, only one was sustained.

Once the DPA sustains a case, it recommends a measure of discipline based on its findings. The Chief of Police determines if the sustained allegation has merit and what if any level of discipline or corrective action to impose. An officer can still appeal the chief’s decision to the Police Commission. The DPA can also send findings directly to the Police Commission, but only if the DPA considers the level of discipline should be higher than a ten-day suspension of the officer involved, and that is a rare occurrence.

The Police Officer’s Bill of Rights (POBR), a California state regulation, also bars the Police Commission, the DPA, SFPD Internal Affairs and SFPD from revealing information about officer misconduct and any discipline measures issued that would in any way identify the specific officer. For this reason, information about police officer misconduct (past or present for that matter, in San Francisco or elsewhere) is hard to come by; making it even more difficult to develop evidence-based policy to curb abuses. With effort, a citizen watchdog could laboriously create an informative and statistical database based on available information already published to track performance across the Police Commission, the DPA and SFPD Internal Affairs. But that only begs the question as to why these institutions are not already implementing a policy of transparency based on the best principles of open government that helps city residents increase our understanding of police misconduct. When it comes to ending police impunity, San Francisco continues to drive blind.

The question now is whether the next mayor of San Francisco plans to harbor police abuse and impunity as did Mayor Ed Lee, or combat his legacy.