Mt Davidson

Historical Essay

by Jacquie Proctor

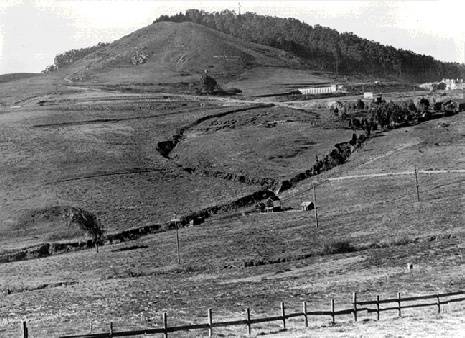

Mt. Davidson with cement cross erected in 1934, viewed from northeast, looking southwest.

Photo: Private Collection, San Francisco, CA

Same angle in 2006.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

At 938 feet above sea level, Mount Davidson is the highest of San Francisco's hills. Located near the geographic center of the city, southwest of the crossroads of Portola Drive, O'Shaughnessy, and Laguna Honda Boulevards, it is accessible by the 36-bus line. Covered with trees planted by a Comstock Lode millionaire on the west and native plants on the east, it quietly remains an open space oasis in the midst of the densest city in California. Its rugged red rock outcroppings are made of melange terrane, 100-million-year-old radiolarian chert that once formed an ancient ocean floor. While not a famous tourist destination, the story of the city's highest point and the world's tallest cross at its summit reflect the major events that shaped San Francisco's history and reputation.

Many of those who held the city's highest office or made their fortune in the Gold Rush would seek ownership of the city's highest point. The first to do so was the last mayor or alcalde of Yerba Buena, Don Jose de Jesus Noe. He acquired it as part of a 4443-acre land grant called San Miguel Rancho, granted by the Mexican Governor Pio Pico in 1845. After California's statehood and discovery of gold, the validity of such land grants was questioned. By 1854, "California's First Farmer," James Horner, was then able to buy the rancho for a mere $200,000. He sold it to shipping millionaire and Mayor of San Francisco C.K. Garrison three years later.

A Frenchman named Francois Pioche, also drawn to California by the Gold Rush, became the next owner of the City's highest hill. Born in France in 1818, he left home to become chancellor to the French consul in Chile at the age of 30. He came to California with his partner, J. B. Bayerque, in 1850. Pioche initially opened a small business, and then decided to go back to France to sell the new opportunities he saw in California. Returning to San Francisco with six million francs in investment capital, he proceeded to earn millions of dollars. He funded construction of the first railroad in California and not only purchased San Miguel Rancho, but also Bernal Ranch and tracts in Visitation Valley, Hayes Valley, and the Western Addition. To get people to his property, he helped finance the Market Street and San Jose Railroads. He also discovered and bottled the mineral water at New Almaden and founded the French Hospital. The pioneer financier and bon vivant is credited with giving San Francisco an appreciation of fine food. At one time he brought forty chefs and a cargo of vintage wine from France to give San Franciscans the benefit of the "Grand Tour" and improve the local restaurant cuisine. Men and women of importance in social, financial, and artistic circles looked forward to lavish parties hosted by Pioche at his home 806 Stockton Street on a weekly basis.

While Pioche was adding to his land holdings via defaulted mortgages, German immigrant Adolph Sutro was mining the original Mt. Davidson (also named after surveyor George Davidson) in Nevada. He had come to San Francisco in 1850 and headed to Nevada in 1859. The two men who had discovered silver on Mt. Davidson had failed to enjoy its riches because they died shortly after their discovery. As a result, the mountain was said to curse those who found its secret. But Sutro was not deterred. He was also able to solve the problems of ventilation and drainage after going back East and to Europe to obtain the necessary capital. His five-mile tunnel into the silver-rich Comstock Lode made him and his partners multimillionaires by 1878. One of his first investments in 1881 was 1400 acres of the San Miguel Rancho. By the time of his death in 1898, Sutro had also become Mayor of San Francisco and the owner of one tenth of the city, approximately 12,000 acres (from Baker Beach and Lincoln Park to the shores of Lake Merced). At the urging of the naturalist poet, Joaquin Miller, he enlisted school children and the unemployed to plant eucalyptus and pine trees on his land for Arbor Days, transforming the city's barren mountaintops and creating the thick Sutro Forest that remains on Mt. Davidson today. As would later be done on his highest peak, he crowned another of his San Francisco peaks Mt. Olympus and erected a lit monument called Triumph of Light, "to inspire our citizens to good and noble deeds for the benefit of mankind." Sutro then willed his original 1,400 acres to his heirs as an educational trust. His heirs, however, were more interested in the value of the land, and they eventually convinced the California Supreme Court to invalidate Sutro's will. The year they sold the land to their appraiser, A.S. Baldwin, the Sierra Club hiked into the "little wilderness of the Sutro Forest" to hold a ceremony renaming the peak in honor of their charter member and President of the Academy of Sciences, George Davidson. Mt. Davidson's new name was officially recorded in 1911.

"For the pleasure of the public," A.S. Baldwin proceeded to invest $2,000 for construction of hiking trails to the top of Mt. Davidson. One of those who hiked up in 1920 was James Decatur, a Western Union official and director of the YMCA. Inspired by the natural surroundings, he set out to describe what can still be experienced today. "As the group found themselves deeper in the wood...peace and quiet were so profound that it seemed almost unbelievable that the noise and roar of a great city was only a few minutes behind them.… The solitude of the forest...conveyed a sense of vastness quite as real as one would experience among the age-old monarchs of the High Sierras.…The undergrowth and flowers looked as if they might have been there for centuries.…[At the summit was] a clear vision of the great panorama that spread before the eye....on the far eastern horizon stood the bold figure of Mt. Diablo, to the west could be seen the boundless Pacific, with the headlands of Point Reyes and Point San Pedro forming widespread arms of welcome to those who enter the Golden Gate. [Below were] tall monuments of steel and concrete wherein were housed thousands of busy minds.…Myriads of moving objects were, without doubt, hurrying hither and thither, all within vision of Mt. Davidson, yet the noise and tumult of it all was absent."

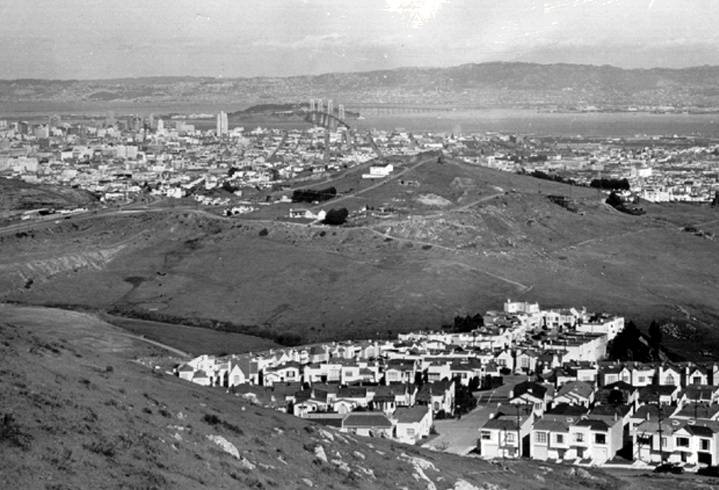

View of downtown from Mt. Davidson, 1939.

Photo: Private Collection, San Francisco, CA

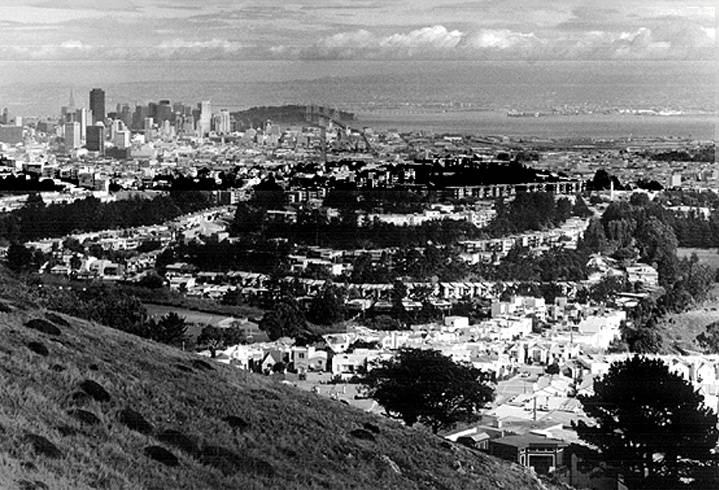

View of downtown from Mt. Davidson, 1994.

Photo: David Green

View of downtown from Mt. Davidson, 2005.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

James Decatur's subsequent efforts to build "a cross to crown San Francisco's highest point" would ultimately lead to preservation of the area as a city park. Spanish explorers and Catholic priests had placed crosses throughout California in the 1700s. By the 20th century, a new wave of immigrants was seeking spiritual meaning in natural settings and building crosses on mountaintops to counter the commercialism and materialism they perceived in modern life. In just one day, Decatur raised $1,100 in donations for the newly-formed Easter Sunrise Committee. This was used to build a forty-foot-high wooden cross for the first Easter Sunrise Ceremony on April 1, 1923. J. Wilmer Gresham, the dean of one of San Francisco's largest churches, Grace Cathedral, led the event. Despite the rain 5,000 people attended. Boy Scouts and Boy Pioneers camped out the night before and kept bonfires burning to light the way for worshippers arriving before dawn. Search lights illuminated the cross for (according to the San Francisco Chronicle) "boys and girls in hiking togs, Jew and Gentile, men and women in heavy wraps, Catholic and Protestant to trudge up the long winding pathways leading to the glowing cross."

With the popularity of this civic gathering, James Decatur received donations from A.S. Baldwin and others to build a more permanent 87-foot-high cross. When it burned to the ground a year later, donations were solicited for a third one. At the same time, Baldwin (like Sutro) found fortune with a tunnel. This one was constructed through Twin Peaks in 1917 to bring downtown workers to the new homes he was building on the slopes of Mt. Davidson. Mrs. Edmund N. "Madie" Brown, ardent nature lover and State Park Commissioner, began a campaign in 1926 to stop "the subdivider's axe and steam shovel from destroying in ruthless fashion the beauties of nature on our beloved Mt. Davidson." She made a plea for help to the Commodore Sloat School Parent-Teacher Association "to preserve for San Francisco this wooded hill, Mt. Davidson, which will serve to provide our school children with the environment for nature study, the Boy Scouts with an outdoor playground for hikes and overnight camping, the Easter pilgrim with a place of worship on its summit at dawn, and the visitor with unsurpassed views from the highest point in the city." The mothers and their children volunteered to collect wildflowers to send to individuals as pleas for support. Exhibits were arranged for display at flower shows and schools. With their recent 19th amendment rights, the 15,000-member City and County Federation of Women's clubs joined the campaign to preserve Mt. Davidson as a city park. Prominent citizens were interviewed, letters were written to individuals and organizations asking for their support, and publicity was secured through press and movie newsreels. This grassroots effort resulted in a popular demand for the preservation of the city's highest point.

The sum of $15,000 was appropriated by the city to purchase the first 20 acres in 1927 with the support of Mayor Rolph (who served four terms and would become governor) and the first woman elected to the Board of Supervisors, Margaret M. Morgan. The land was dedicated as a city park on the 84th birthday of Park Superintendent John McLaren in 1929. The same year, James Decatur succeeded in building a third and more permanent cross for the sunrise ceremony. It was seventy-six feet high, set in a concrete base and covered with stucco and three hundred lights. It lasted two more years until it, too, burned. A fourth temporary cross was built, but plans were underway with the help of the Native Sons and Native Daughters of the Golden West to build a bigger and stronger monument. Before 32,000 attendees at the 1932 sunrise event, Governor Rolph dedicated the cornerstone of the new 103-foot-high concrete cross. Inside it was a transcript of the original title to Mt. Davidson signed by the first Mexican governor of California.

The monument would be located on the six-acre summit donated by Mrs. A.S. Baldwin and designed by a leading architect of the time, George W. Kelham, Chief of Architecture for the Panama-Pacific International Exhibition in 1915. He came to San Francisco to rebuild the Palace Hotel after the 1906 earthquake and went on to design the historic Main Library, the art deco Shell Oil Building, and the thirty-one story Russ Building at 235 Montgomery Street. Built in 1927 and the tallest building in San Francisco until 1964, the Russ Building was the first to have an indoor parking garage. His partner for these projects was Henry J. Brunnier, consulting engineer for the San Francisco-Oakland Bridge, the longest steel high-level bridge in the world. Brunnier would survive Kelham and go on to build an even taller skyscraper for the Bank of America. These creators of San Francisco's world famous skyline would build their only monument on its highest point. Like their massive skyscrapers and bridges, the cross they designed is constructed of concrete (seven hundred fifty cubic yards) and steel (30 tons). The foundation, 18 feet in diameter at the bottom and 14 feet at the top, extends 16 feet down into solid rock. The 103-foot concrete shaft is 10 feet wide at the base and tapers to 9 feet at the tip, with nine-foot-square arms that measure 39 feet from tip to tip.

In the midst of the hardship and conflict of the Great Depression, union members and business leaders, homemakers and politicians, children and the unemployed, came together to raise funds for the Mt. Davidson Cross. Other monuments to economic recovery included the Golden Gate and Bay Bridges and the Empire State Building; these were dedicated by presidential lighting ceremonies. Madie Brown wrote a letter to President Roosevelt in 1934 asking him to dedicate the cross in such a fashion. "As chairman of arrangements, I have dared to dream that you would press a button in Washington, D.C., which in turn would light for the first time this giant cross in San Francisco at its dedication on March 24. It seems most appropriate that you, who have brought light to many a darkened American home and who through your New Deal has instilled the principles of the Golden Rule into American business, should take part in this cross-lighting ceremony." President Roosevelt agreed, and pressed a golden-keyed telegraph switch to light the cross at 7:30 PM before a crowd of 50,000-just two days after successfully convincing the International Longshoremen's Union to postpone their General Strike planned for the day before.

While mayors can no longer own the city's highest point, they continue to make the annual pilgrimage to its summit for the Easter sunrise service. During the remainder of the Depression and through the early 1940s, CBS Radio broadcast the sunrise services coast-to-coast. The level of attendance and expansion of the park coincided with subsequent historic events. Seven acres were added to the park in 1941, as up to 75,000 attended the Easter events during World War II. The last of the 38 acres of Mt. Davidson Park were purchased in 1950, and funds were subsequently raised to light the cross year-round after a soldier bound for Korea wrote of it being his last sight of home. The lit cross can still be seen in the 1971 film Dirty Harry, in which Clint Eastwood engages in a dramatic struggle at its base. Visible from 75 miles away, the twelve 1000-watt lights were turned off in 1976, except during Easter and Christmas weeks, because of the energy crisis. Live television broadcast of the sunrise ceremony began in 1977 with national coverage by CBS in 1979 as attendance surged in response to the assassinations of Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk.

After the lighting of the Golden Gate Bridge was expanded in 1987, fundraising began to resume year-round lighting and obtain historic designation of the cross. However, in response to complaints that public ownership of a religious landmark was a violation of the separation of church and state, the city restricted the lighting to two hours before Easter sunrise. A subsequent lawsuit took ownership of Mt. Davidson to the California Supreme Court a second time. The importance of preserving the site as a city park would be used as an argument for removing the monument. Barely visible amidst the trees and dwarfed by a nearby transmission tower named for Adolph Sutro, nine times its size, the Supreme Court ruled that the cross was a violation of the California Constitution for being on the city's highest point. (An offer by master artist Beniamino Bufano to erect an even taller 180-foot-high sculpture of St. Francis on the top of Twin Peaks in 1938 had been declined.) After a five-year battle, the city was forced to sell the parkland under the cross at a public auction to the highest bidder, or remove the historic monument. Neighborhood leaders negotiated limitation of the property transfer to .38 acre, with deed restrictions ensuring public access and protection of the open space in perpetuity. A campaign like the one initiated by Madie Brown convinced San Francisco voters to overwhelmingly ratify the sale of the landmark to the auction's highest bidder, the Council of Armenian American Organizations of Northern California, in November of 1997. The historic lights turned on by President Roosevelt were removed, but portable lighting of the cross is allowed two days a year. This Depression-era public art project continues to be lit on Easter eve as a testament to the ideals of preservation and civic spirit.

Jacquie Proctor is one of the founders of the Friends of Mt. Davidson Conservancy.

Bibliography

Rosalie Kuwatch, Miraloma Park, A Suburb within a City (San Francisco: City College, 1984)

Marie Bolton, The Contemplative Ideal in Public Space: The Cross at Mt. Davidson Park (San Francisco: City Attorney, 1991)

William Benedict, The Story of Mt. Davidson (San Francisco: The Municipal Employee, 1928)

QUICK FACTS

Blue Mountain was mapped in 1826 by British explorer Frederick Beechy

Adolph Sutro purchased Blue Mountain in 1881

In 1911, Blue Mountain was renamed Mt. Davidson in honor of George Davidson, President of the Academy of Sciences