Chinese New Year Parade

Historical Essay

by Kye Masino, 2019

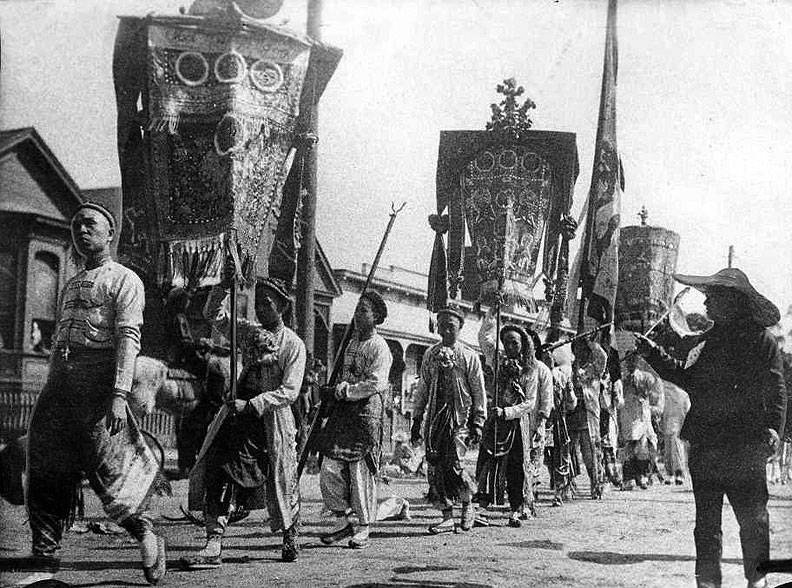

| Hoping to ameliorate negative prevailing opinions and reconnect with their homeland’s customs, the immigrant Chinese community constructed a uniquely fantastical solution. In the 1860s, immigrants organized the Chinese New Year Parade, unlike anything held in China, to display their traditions and customs (4). The parade’s success, which continues today, presented the first of many steps toward the assimilation of Chinese peoples into American society. |

Early Chinese New Year Parade, n.d.

Photo: San Francisco Chronicle

With the advent of the Gold Rush in the mid-1800s, San Francisco experienced a surge in Chinese immigration. Many Chinese migrants sought reprieve from the socioeconomic climate of southern China- a region marred by impoverishment and hunger. San Francisco, the fledgling metropolis with seemingly ever-expanding industry, appeared an ideal place for foreign settlers to start a new (3).

Despite a growing presence in the city, individuals of Chinese lineage endured extensive prejudice from fellow San Franciscans. The city’s majority white, male populace’s view of Chinese culture and customs was largely contemptuous. In spite of this antagonistic environment, the Chinese community launched an initiative to combat disparaging public perception in 1860. In an innovative fusion of Asian and American cultures, the community devised the Chinese New Year Parade: an event which would become emblematic of its representative community’s perseverance.

Not unlike other contemporary representations of Chinese culture, the authenticity of a Chinese Parade is dubious at best. In exploring the relevancy of parades to Chinese culture, David Lei, son of a parade organizer and former volunteer noted: “The Chinese New Year Parade in San Francisco was made up. It's purely American like chop suey or the fortune cookie” (1). Despite the event’s fictitious premise, Chinese San Franciscans enjoyed numerous benefits with its commencement.

The parade allowed immigrants the opportunity to embrace their traditions in public space. Of these practices, Chinese immigrants’ fondness and aptitude with fireworks was of particular pertinence. Pyrotechnics’ role in Chinese culture extended far beyond visual appeal, as their use was believed to ward off evil spirits (7). Some may question the value of remembering such folk superstition, but as Chiou-Ling Yeh, professor of Asian-American Studies at San Diego State University explains, “ These old world rituals served as a link between immigrant and their home countries and created a sense of community in their adopted country” (7). This togetherness likely contributed to Chinese immigrants’ resilience in facing tremendous hostility.

Former Attorney General of California, Frank Pixley, encapsulated the prevalent antagonism and outright hatred of Chinese peoples during his 1876 address to the state, remarking, “the presence of these people in our midst has a tendency to demoralize society and minister to its worst vices; it aids to corrupt and debauch our youth, and the labor of this servile class comes in direct competition with the labor of American citizens. It degrades industrial occupation, drives white labor from the market, multiplies idlers and paupers, and is a menace to Christian civilization” (6). His racially charged diatribe portrayed Chinese peoples as both an economic and moral threat. Of course, this sentiment had already corrupted the ethos of San Francisco years prior; Pixely acted as a conduit to further spread the vitriol.

In spite of hateful public discourse, the parade carried on relatively unencumbered past the 1870s and into the 1900s. These early demonstrations occurred along then Dupont (now Grant) and Kearny Street. Participants wielded ornate flags and booming percussive instruments, juggled with the occasional exhibition of pyrotechnics.

Such fiery displays were shortlived, as local government eventually placed restrictions on fireworks, allegedly due to noise concerns. Historians now speculate that these regulations were oppressive in intent, as events outside the Chinese community utilized similarly noisy displays while remaining unprosecuted (7). These discriminatory policies, alongside the implementation of the Chinese Exclusion Act, furthered political disenfranchisement among the immigrant community (7).

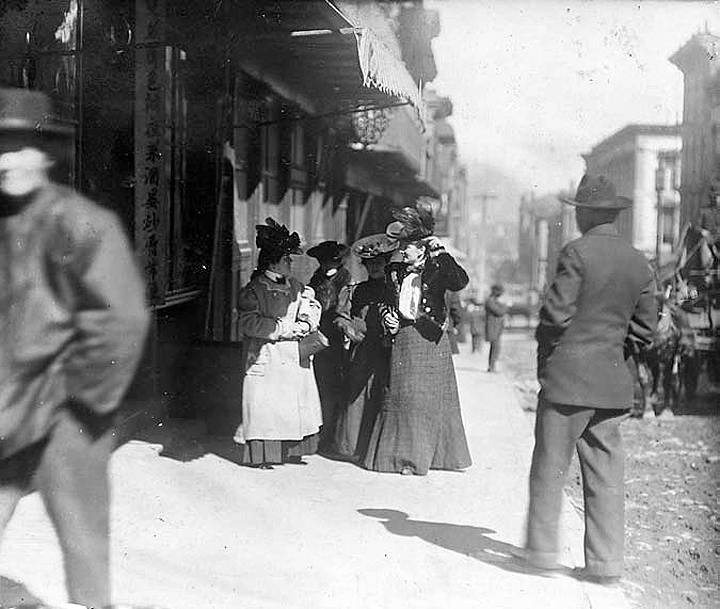

Several years following these events, the transformation of Chinatown after the 1906 earthquake foretells the parade’s metamorphosis in the 1950s. The destruction of 1906 devastated Chinatown, reducing much of the district to rubble and endangering its inhabitants with the threat of displacement. However, in the destruction, some saw an opportunity. Legend of Chinatown’s unique cultural offerings had already spread across the country and even abroad. Tourists and locals alike peckishly perused the area to sate their curiosity, as displayed below. (2) Their interest generated cash flow.

White women walking through Chinatown. Chinatown quickly emerged as a curiosity and an organized site of urban tourism for city visitors as well as non Chinese San Franciscans.

Photo: Chinese in California, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

So began the initiative to rebuild Chinatown for the tourists’ gaze, to create the ultimate Western fantasy of the exotic East. The project proved a great success. Tourist literature lauding the mysterious marvels of Chinatown became widespread, rekindling interest in the area.

Several decades later, in the wake of World War II, W.K. Wong, an influential figure in the Chinese-American community, took command of the parade. Partly driven by the same financial incentives which transformed Chinatown, Wong expanded the parade to maximize its reach, allowing for multicultural entries and even a fashion show (5). An attached image captures some of the first non-Chinese parade participants in the 1953 parade (Bragman).

Bagpipers in the 1953 Chinese New Years Parade on Grant Avenue

Photo: San Francisco Chronicle

Wong’s bold stewardship of the event paid off, as the 1953 Chinese New Year Parade helped propel the event to its current legendary status and supported the local economy. That said, focusing on the monetary benefits of the parade may neglect its true importance to the Chinese community.

Indeed, San Francisco’s not so distant internment of Japanese Americans weighed heavily on the Chinese community. With mounting political tension between China and the U.S., Chinese Americans feared a similar fate could befall them, as recounted by Lei, stating, “There were grave concerns that the Chinese will be rounded up and put in camps” (1). The parade offered a chance to alter public perception, potentially dampening the endemic discrimination characteristic of the era. Unlike in the 1860s, the stakes of widespread racism had become fully realized through observation of the Japanese’s peril.

Perhaps the success of the 1953 and subsequent Chinese New Year Parades mitigated the likelihood of a second racial exodus. Indeed, the event functioned as an endorsement for the value of Asian culture. Furthermore, the parade’s explosion in popularity coincides with the rise of the “model minority” archetype, suggesting the festivities likely contributed, along with countless other factors, to easing racial tensions. The Chinese Chamber of Commerce's election to assume command over the event after 1958 fortifies the evidence in favor of its vital importance to the Chinese San Franciscan community.

With San Francisco’s current cosmopolitan allure, some may praise the Chinese New Year Parade as a beautiful display of metropolitan multiculturalism. However, many historians dispute this viewpoint. They argue that despite improving racial tensions, the parade’s role in helping to spread the “model minority” archetype has furthered American racial ideology, fostering a sense of otherness in the Chinese community (7). Thus, one could reason that the event has exerted a net negative impact on the community. Yet, the converse argument in favor of the parade appears equally valid. The proud, outward expression of one’s identity, inherent in a parade, has allowed an oppressed community to empower themselves for over a century. In truth, we may never be able to assert the parade ‘s true impact, detrimental or positive, conclusively. Whatever its past influence, the Chinese New Year Parade exists today as a symbol of unity and perseverance despite constant opposition.

Notes

(1)“A Chinatown Tradition, San Francisco’s Chinese New Year Parade Is ‘American like Chop Suey.’” NBC News, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/chinatown-tradition-san-francisco-s-chinese-new-year-parade-american-n847661. Accessed 23 May 2019. Bragman, Bob, and SFGATE. “In 1953 ‘outsiders’ Were Invited to SF Chinese New Year Parade - 140,000 Showed Up.” SFGate, 10 Feb. 2017, https://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/In-1953-outsiders-invited-to-SF-Chinese-New-10862478.php.

(2) Chinatown’s 19th Century Tourist Terrain - FoundSF. http://www.foundsf.org/index.php?title=Chinatown%27s_19th_Century_Tourist_Terrain. Accessed 26 May 2019.

(3) Chinese Immigration - FoundSF. http://www.foundsf.org/index.php?title=Chinese_Immigration. Accessed 24 May 2019.

(4) “History.” Chinese New Year Parade, 30 July 2018, https://chineseparade.com/history/.

(5) Nee, Victor, and Bratt de Bary. Nee. Longtime Californ': a Documentary Study of an American Chinatown. Stanford Univ. Press, 1990.

(6) Scribners Monthly. Scribner & Company, 1876.

(7) Yeh, Chiou-ling. Making an American Festival: Chinese New Year in San Francisco’s Chinatown. University of California Press, 2008

(8) “移民史関係 : UC Berkeley 滞在記.” UC Berkeley 滞在記, http://berkeley.blog.jp/archives/cat_239250.html. Accessed 24 May 2019.