Ad Hoc Beatniks

Historical Essay

by Ammar Alqatari, 2019

| The Ad-Hoc Committee to End Discrimination played an instrumental role in the organization of the San Francisco civil rights movement during 1963-64. The group, formed mostly by young members of the Du Bois Clubs, organized and lead the seminal protests at Mel’s Drive-In and the San Francisco Sheraton-Palace Hotel. The group’s use of direct action and confrontational tactics stirred controversy but ultimately achieved significant concessions for fair employment practices for African Americans in San Francisco, helped place the city on the national map of civil rights activity in the 60s, and paved the way for more militant and radical organizations and movements to emerge in the Bay Area in the late 1960s. |

Ad Hoc Committee Button

Source: https://jofreeman.com/sixtiesprotest/baycivil.htm

As the civil rights movement in the South gained national momentum, northern and coastal cities like San Francisco began to scrutinize their own communities and organize against the ingrained inequalities which still lingered in practices like employment, housing, and police brutality. A wave of civil rights demonstrations took place in San Francisco in 1963 and 1964 which achieved substantial reforms towards racial equality in the Bay Area. Though national organizations like the NAACP and the Congress On Racial Equality (CORE) played a lead role in the movement, often overlooked is the instrumental role of the Ad Hoc Committee to End Discrimination, a group of radical students and Bay Area youth, in instigating and galvanizing energy for the movement. The Ad Hoc Committee was the lead group in organizing two of the first major actions of the movement: the picketing of Mel’s Drive-In and the sit-in at the Sheraton Palace Hotel protesting their hiring practices. Through their insistence on direct action and use of confrontational tactics, the Committee represents the beginning of a younger and more militant contingent in the civil rights movement in the Bay Area which paved the way for the campus free speech movement and helped set the stage for a more radical black politics to emerge in the late 1960’s.

The Ad Hoc Committee to End Discrimination emerged at a period in San Francisco marked by growing awareness and dissatisfaction with the state of black civil rights in the city coupled with the radicalization of Bay Area youth. The black population in San Francisco had swelled to around 10% of the city’s population by 1960 and constituted close to half the population in neighborhoods like the Western Addition. Unemployment in the African American community drastically increased with the growth of the population, and the racist roots of the problem was not lost on the community—as one man commented in 1961: “the white man tolerates the Negro so long as he isn’t here in large numbers. San Francisco’s a strange place. You’re called a mister and can eat in the fanciest restaurants, but you can’t find a job” (8). The period witnessed the growth and consolidation of many black organizations, including the establishment of a San Francisco chapter of CORE in 1960, new leadership and campaigns in the San Francisco NAACP, and the union of the two along with other black organizations under the umbrella of the United Freedom Movement (UFM) in 1963. What was unique to San Francisco, however, was the presence of a contingent of young whites eager to stand in alliance with the black community. The 1960 City Hall Riots against the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings in San Francisco by students from UC Berkeley, Stanford, and SF State College alerted the city to such a presence of disgruntled white middle-class youth ready to organize (5).

The Ad Hoc Committee to End Discrimination formed in this ripe climate for organization in an ad hoc manner, as its name suggests, primarily born out of the membership of the W.E.B. Du Bois Club. The Du Bois Club was a youth organization sponsored by the Communist Party with the intention of attracting non-Communist youth, educating them, and eventually recruiting them into the party (9). The predominantly white group claimed to be “independent of any parent organization” in its pamphlets, describing itself as dedicated to “building a socialist movement” and using militant action to “solve the immediate problems of Americans of all races, ages, and nationalities” (11). Members received activism training from the Community Party (10) and, through working with African-American youth in the Bay Area, learned of the prevalent discriminatory employment practices which relegated African- Americans to the lowest paying, most menial, and least visible jobs in the service industry. The discriminatory practices had persisted in spite of the passage of the Fair Employment Practices bill in the California legislature in 1959, heavily pushed for by the NAACP, which “prohibited employers or labor unions from discriminating on the grounds of race, creed, national origin or age” (3). The Du Bois Clubs activists identified prominent targets which discriminate against African Americans in their hiring practices and decided to organize against them (2). As the activists evolved into the Ad Hoc Committee Against Discrimination over the course of their campaign, the group centered the charismatic 18 year-old black activist Tracy Sims who became the chairperson, spokesperson, and public face of the demonstrations.

One of the first successful actions of the civil rights movement was the picketing of the Select Realty Agency in San Francisco by members of the Du Bois Club, CORE, and NAACP in August of 1963. After the arrest of 11 activists and negotiations for several months, the picketers reached an agreement with the Agency to end its discriminatory hiring (12). Though smaller and not very well publicized, the action set a template for the major actions of the movement which took place over the course of the following year.

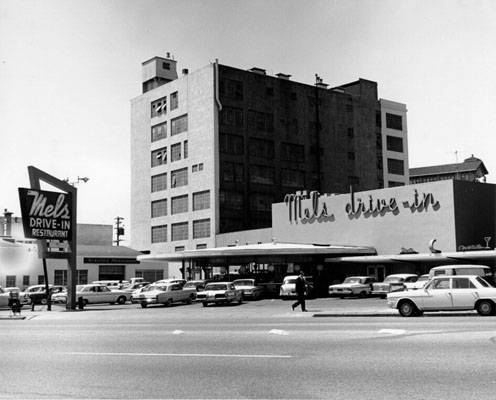

Mel’s Drive-In on Geary Blvd.

Source: http://online.sfsu.edu/socialj/photos/mels/2melsphoto.jpg

The next target identified by the Du Bois Club was Mel’s Drive-In, a Bay Area restaurant chain which members learned didn’t hire black waiters. The restaurant was a prime target as it was owned by Harold Dobbs, a city supervisor running in the mayoral election. It is over the course of this campaign that the Ad Hoc Committee to End Discrimination emerged as a larger group combining the core membership of the Du Bois Club with activists from SF State College (mainly Black Student Union members who organized themselves as the Direct Action Group) along with other UFM groups (1). The action began in October of 1963 when members of the Du Bois Clubs and DAG picketed Mel’s locations on Geary and Van Ness streets, asking for an anti-discriminatory hiring and promotion policy, training for all employees regardless of race, employing a certain number of employees from minority groups, and hiring African-Americans in visible positions like cashiers and bartenders (5). When the restaurant refused to meet their demand, the protestors escalated by picketing Dobbs” home in November 1963, less than a week before the election which he lost. The activists, who at that point went by the name of the Ad Hoc Committee to End Discrimination, followed-up the pickets with a mass sit-in which occupied all the seats of a Mel’s location in San Francisco, leading to the arrest of more than 100 (3). Less than a week later, Mel’s agreed to settle for their demands, agreeing to hire African Americans “up front” from then on (6).

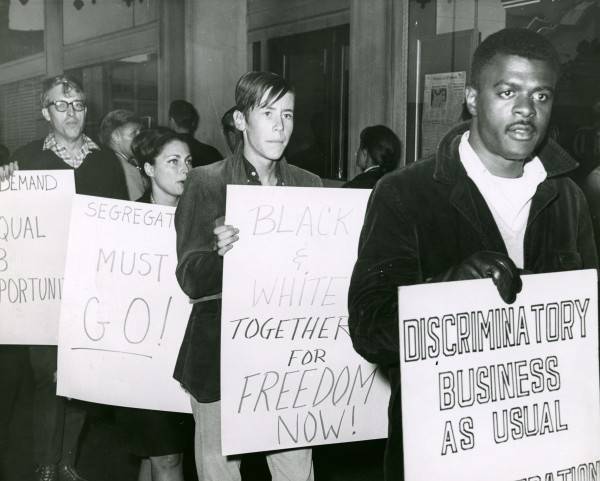

The Ad Hoc Committee to End Discrimination followed that success with an action matching the same template, though at a larger scale than any previous action, with the picketing of the Sheraton Palace Hotel in March of 1964. Initiated by a couple dozen members of the Committee, the protest soon swelled with African American residents of the Western Addition and activists from around the Bay joining to reach over 1000 pickets. The action stands out among other civil rights demonstrations around the nation for its notable interracial solidarity, with around 60% of the protestors being white (13). The massive demonstrations attracted thousands of spectators who reportedly “clogged” Market and New Montgomery streets. The hotel association denied the legitimacy of the Committee, accusing it of being “not a true civil rights group” and a front group for the “Marxist-oriented” Du Bois Clubs, which the Committee countered by describing itself as a collection of “Socialist Action youth groups’. The picketers didn’t shy away from confronting police during the demonstrations. More than 167 protestors were arrested over the course of the pickets, which gave even more public attention to the protest, although all were freed except for Tracy Sims who was sentenced to 90 days in jail (13). After a long stand-off and multiple rounds of negotiation between the attorney of the Ad Hoc Committee, Terry Francois, and the Palace Hotel attorney, the Committee reached a settlement with the hotel which met all their demands.

Sit-in in lobby of Sheraton Palace Hotel, March 7, 1964.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

The scale of the protest, the success of its confrontational tactics, and the tacit approval of Mayor John Shelley provoked strong public reactions to the events at the Palace Hotel. White San Francisco residents berated the mayor for supporting the result of the demonstrations and decried what they saw as a concession against white interests. “It is shocking that you would allow such a victory of ad-hoc beatniks over big business! It is shocking you would allow a group of wild, fanatical, communistic students to prevail!” cried a “group of irate residents” in a letter to the mayor (14). The Committee was perceived by white residents of the city as a group of “beatniks, fairys, and most likely commies” (15) and as “misfits, crackpots, exhibitionists” (16).

The direct action approach of the Committee stirred contention not only among white city residents but also within civil rights organization like the NAACP. While the local chapter of the NAACP released a statement recognizing “the beneficial results flowing from the successful efforts of the Ad Hoc Committee to End Discrimination’, the regional secretary for the NAACP denied her organization supported the demonstrations (8). San Francisco’s human relations coordinator, James Mitchell, also detracted from the demonstrations, claiming they alienated “people who might be sympathetic to or mildly interested in the cause of the Negro” (8). The action finally resulted in a split between the NAACP when its president stated: “I'm not at all certain I can continue to work with them under these circumstances—not when my advice is given so little consideration.” (7). The group was regardless soon coming to an end; the arrests of Tracy Sims and the trials of hundreds of Committee activists had taken their toll on the Committee which had led small demonstrations in Oakland soon after the Palace Hotel demonstrations, but soon dissolved in the Fall of 1964 (4).

Members of the San Francisco Ad Hoc Committee To End Racial Discrimination protest outside the Oakland Tribune building in downtown Oakland, California, demanding an increase in minority employees at the paper, September 4, 1964.

In spite of these negative initial reactions to the Palace Hotel demonstrations, however, the momentum carried over to further successful actions against Bank of America lead by CORE and UFM, and protests against the Cadillac Agency in San Francisco’s Auto Row led by the NAACP. The legacy of the employment fairness protests further paved the way for the campus free speech movement, with many of the activists moving on to organizing on the campuses of US Berkeley and SFSC (17), including Mario Savio who was present at the Sheraton Hotel picket on March 6th (4). As the activists escalated in the militancy of their tactics, so did the conservative sectors of corporations and government escalate in their degree of backlash. The same activists of the 1963-1964 civil rights movement became attracted to more militant approaches, with CORE activists turning towards black nationalism and more radical approaches of social struggle (17). Though the Ad Hoc Committee to End Discrimination was short-lived, it left a strong legacy of interracial solidarity, youth organization, and use of direct action which inspired more militant later generations of San Francisco activists and placed San Francisco on the national map of civil rights activity in the 1960s.

Notes

1. Moncur, Tracy. “Tamam Tracy Moncur Interview Clips.” online.sfsu.edu/socialj/audio- visual.html. Accessed 10 June 2019.

2. Link, Geoffrey. “Dobbs Gets Picket Treatment.” SFSU Gator, October 23, 1963, http://online.sfsu.edu/socialj/Mels/22a%20-%20nov12%20mel's%20victory.jpg.

3. Fuselier, Pierre. “Pickets, Dobbs Finally Agree.” SFSU Gator, November 12, 1963, http://online.sfsu.edu/socialj/Mels/22a%20-%20nov12%20mel's%20victory.jpg.

4. Freeman, Jo. "From Freedom Now! to Free Speech: How the 1963-64 Bay Area Civil Rights Demonstrations Paved the Way to Campus Protest." Jo Freeman. com (Retrieved July 20, 2010, http://www.jofreeman.com/sixtiesprotest/baycivil.htm) (1997).

5. Salomon, Larry. “The Movement for Jobs in Civil Rights Era San Francisco, 1963-64.” San Francisco State University, 1994, http://online.sfsu.edu/socialj/context/context13.pdf.

6. Crowe, Daniel E. Prophets of Rage: The Black Freedom Struggle in San Francisco, 1945-1969. New York: Garland Pub, 2000. Print.

7. “The Civil Rights Movement in The Bay Area - Google Arts & Culture.” Google Arts and Culture, The Bancroft Library, http://artsandculture.google.com/exhibit/ARtzEd5p.

8. Miller, Paul T. The Postwar Struggle for Civil Rights: African Americans in San Francisco, 1945-1975. New York: Routledge, 2010. Print.

9. Francis X. Gannon, Biographical Dictionary of the Left: Volume 2. Boston: Western Islands, 1971; pg. 181.

10. California State Senate, Thirteenth Report of the Senate Fact-Finding Subcommittee on UnAmerican Activities. Sacramento: Senate of the State of California, 1965; pg. 37.

11. Du Bois Club Pamphlet. http://online.sfsu.edu/socialj/context/context3.pdf

12. “Select Realty Pickets.” Bay Area Social Justice History Project, http://online.sfsu.edu/socialj/index.html.

13. Trimble, Peter. “1000 Picket Hotel: Rights Protest at the Palace.” San Francisco Examiner, 7 Mar. 1964, http://online.sfsu.edu/socialj/TextScans/Sheraton10.jpg.

14. Received by Mayor of San Francisco, 30 Mar. 1964, San Francisco, California, http://online.sfsu.edu/socialj/results/mayor/Ad%20Hoc%20Beatniks.jpg

15. Peterson, C. Received by Mayor Shelley, 7 Mar. 1964, San Francisco, Califronia.

16. “For Mayor Against Demonstrators.” Received by Mayor John Shelley, 13 Mar. 1964, San Francisco, http://online.sfsu.edu/socialj/results/mayor/Misfits,%20Crackpots,%20Exhibitionists.jpg

17. “Response, Results, and Repercussions.” Bay Area Social Justice History Project, http://online.sfsu.edu/socialj/results.html ]