Bound To Fall: The Hub Neighborhood in Transition

Historical Essay

This article is a summary of a walking tour given by Arthur O'Donnell, The Energy Overseer on October 14, 2018.

If you stand in the middle of the intersection of Franklin and Market Streets, you might get run over by a vintage trolley car from one of 90 other cities around the globe or hit by a bicycle whizzing by. This is Market Street's Brick and Mortar historic district

Photo: Arthur O'Donnell

Future home of the One Oak Project.

Photo: LisaRuth Elliott

Stop One: All Star Donuts, 1500 Market Street at Van Ness Avenue

From this important crossroads, one can clearly envision how San Francisco is changing, both on the surface streets, high above and below ground, where the MUNI light rail runs underground in parallel with historic surface trolleys and the aging BART system. The future vision is that of towering residential buildings, street-level arts and transit hubs, and as many as 9,000 new residential units in a tightly defined zoning area at one of the key corridors into San Francisco’s downtown. Between now and when that vision becomes reality, expect even more construction, traffic bottlenecks, and local controversy.

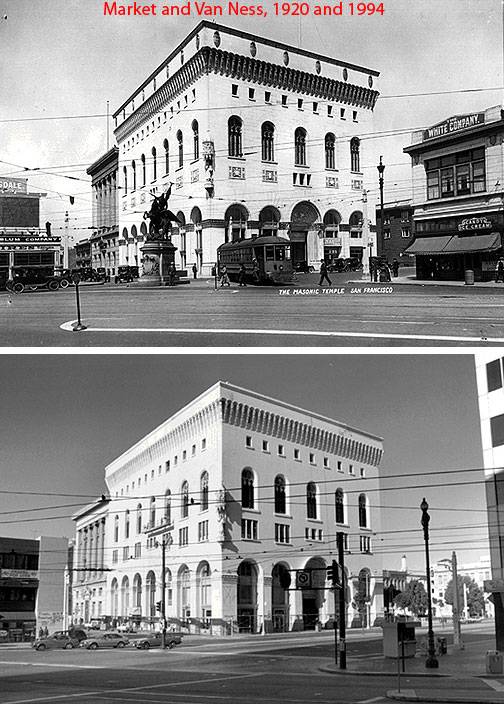

Masonic Temple at 25 Van Ness Avenue, shot from 11th and Market looking northwest.

Photo 1920: Private Collection, San Francisco, CA

Photo 1994: David Green

First take a look at what is here currently: To the North at 25 Van Ness Avenue, the historic Masonic Temple, built following the 1906 earthquake, relocating the Masonic ceremonies and rituals from the former site at Post and Montgomery Streets—where almost nothing survived the great fire. The architects, Walter Bliss & William Farville, also are known for other San Francisco landmarks: the St. Francis Hotel (Powell Street at Union Square), the Savings Union Bank (One Grant Avenue at Market Street #132) and the Geary Theater (415 Geary Street). That’s quite a resume of styles. The white granite is a landmark that can clearly be seen miles away, from the top of Bernal Heights, but soon, it will be obscured by a number of high-rise developments.

On the outside the Masonic is a mix of Medieval and Renaissance Italian influences, with a wise king Solomon figure in contemplation high above the cornerstone, and the Masonic insignia above the gated entry. The inside of the building is worth its own tour, but thankfully, the building is expected to survive—even with its more prosaic occupants: social service offices and quasi-government agencies.

Looking down the street to a row of parking lots and remnants of recently demolished buildings, where Franklin Street intersects Oak Street, the French American International School plans a 31-story tower of residences and administration buildings. Just barely visible from here is an 8-story condo under construction that replaces a single story garage at 22 Franklin Street—a prime example of low density/low value uses giving way to higher density/higher value development. Just before its demolition, the garage had been taken over by squatters in tents, and San Francisco police staged an early morning raid to vacate the site a day before the bulldozers took it down.

But the real story here, where we stand, is the planned One Oak tower and transit hub, with condos that rise 40 stories above the Van Ness and Market intersection, a pedestrian mall that will close off Oak Street to traffic, and refurbished entries to the underground MUNI station. This will provide a modern, more integrated open space plaza for the San Francisco Conservatory of Music building at 50 Oak Street, and its neighbors, with expectations for outdoor retail kiosks, performance areas, planters with seating and a wind canopy.

When announced, the One Oak Tower was expected to be the tallest building in this part of downtown, but it soon attracted several rivals, and we can expect even more proposals to arise after the City adopts a re-zoning and transit plan for The Hub neighborhood perhaps by the end of the year that will allow for a higher density profile in the area. The One Oak development comes as a surprise to most San Franciscans, but within the developer community, city planning agencies and community circles, its has been a controversy that stretches over the past five years…that finally resulted in the developer making low-income housing concessions and winnings its permits—then to turn around and remarket the site for eventual completion. The final environmental impact report, from November 2017, explored such standard issues things as parking (reduced from proposed 155 spaces to 136 as a result of public input and planner pressures) and Native American Cultural Impacts (not applicable at this site) to the wind impacts on bicyclists and other bike hazards, and shadows over a nearby Laguna Street park.

Public art overlay on the block bounded by Market, Oak, and Van Ness Streets, looking northwest.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The area is already being prepared, with recent demolitions on Franklin Street, at 55 Oak Street, and at 1540 Market Street. When the Songbird Mural sings its last note, and the donut shop serves its final glazed pastry, this era of San Francisco will give way to a futuristic tower and transit hub.

The low building at the top right of this photo, 30 Van Ness Avenue will also change when a 520 foot tower is built on top of it.

Photo: LisaRuth Elliott

Across the street at 30 Van Ness Avenue, the city-owned corner building most prominently houses a Walgreen’s. The existing 5 floors will be augmented by a tower up to 520 feet tall—that’s between 42 and 49 stories of office/retail plus 600 residential units, 25% of which will be designated below-market rates. Though taller than One Oak, this development offers little aesthetic improvement to the area, basically it will be a tower on top of a platform. We can only hope that the current building façade that looks like cheap sheeting will be replaced with something more enticing.

View from 10 South Van Ness Avenue looking north in 2018.

Photo: Arthur O'Donnell

Stop Two: Former San Francisco Honda Building at 1595 Market Street and 10 South Van Ness Avenue

In a curious turn of the wheel of fortune, this building, which once was the Carousel Ballroom, and the first iteration of Bill Graham’s Fillmore auditorium empire (now One Nation) before giving way to a succession of automobility dealerships (first Buick, then Honda), is once again expected to house an “event space” at ground level with an open air patio above—at least temporarily. But reaching high above will be a set of two 400-foot residential towers with over 700 units that will rival the One Oak and 30 Van Ness developments and redefine this hub for the remainder of the 21st century.

The iconic Goodwill store at 1580 Mission Street, at South Van Ness Avenue, was demolished on October 30, 2017.

Photo: Arthur O'Donnell

The same site under construction in October 2018.

Photo: LisaRuth Elliott

Stop 3: Former Goodwill site, 1580 Mission Street and Tower Car Wash, 1601 South Van Ness Avenue

When the bulldozers knocked down the iconic Goodwill store on this corner in October 2017, the rounded glass office area briefly lay half sunken and tilted. The timing was somewhat ironic in that this store of secondhand dreams and vintage clothing was one of San Francisco’s top spots for people to piece together their adult Halloween costumes, and first apartment unmatched furniture sets. What really surprised a lot of folks was that this was not a very old building. It was built in the 1990s, as an outgrowth of the former Coca Cola bottling and shipping plant that stretched along Mission Street on the same block.

Block of Mission Street bounded by 11th Street and South Van Ness Avenue under construction in June 2018.

Photo: LisaRuth Elliott

The Coca Cola Clock Tower remains and will be an art deco anchor for a very large office development.

What is planned? One 39-story tower with 540 “luxury” residences, and 462,000 square feet of office complex that will house the San Francisco City Planning, Building, and Public Works Departments.

Tower Car Wash at 1601 Mission Street. Note the matching lighthouse tower in the following photo on the right side of the storage warehouse.

Photo: LisaRuth Elliott

To the south, the Tower Car Wash at 1601 Mission has been targeted for demolition since 2015 to be replaced by a 12 story, 220-unit condo complex. Today a 12-story building would stand out among the relatively low rise surroundings, but it will of course be dwarfed by the 40-story towers planned for the blocks to the north and east.

The public storage warehouse on South Van Ness suddenly looks very low compared to what is planned for the surrounding intersection.

Photo: LisaRuth Elliott

HealthCare360 headquarters in former furniture store on Mission Street at South Van Ness in October 2018.

Photo: LisaRuth Elliott

What remains at this corner? On the south side of Mission Street at South Van Ness Avenue stand a large storage warehouse, a former furniture store turned healthcare administration, what used to be the sushi restaurant Zaoh before it changed hands. There is also a corner vintage shop turned coffee house and further down Mission Street, some brick warehouses that used to house sweatshop clothing manufacturing businesses.

Otis Street at 12th Street and South Van Ness Avenue.

Photo: LisaRuth Elliott

Stop 4: Otis Street

Picture how this short commercial street, called Otis Street, will change in the future. Like many local commercial corridors, Otis Street is now home to business that catered to automobile and motorcycle repairs. This is where you had broken windows replaced, or had your engine tuned up, and could have a taco at the food truck on the wedge of a corner. Or when the job took longer than expected, you could go over to Enterprise and get a short-term rental vehicle.

Let’s look at the future based on current permit applications:

The 12th Street corridor from the corner toward Market Street, will feature a 15-ft wide sidewalk and a 7,000 sq foot pedestrian plaza. Part of the Market Street Hub Public Realm Plan, a development currently on hold.

18 Otis Street

32 Otis Street

38 Otis Street

Photos: LisaRuth Elliott

The five existing buildings between the corner and 80 Otis will be demolished, allowing for construction of a 400,000 sq ft mixed use building with 430 resident units, 2000 sq feet of retail, 15,000 sq feet of arts ,and 230-seat performance space occupied by the City Ballet School. Looking at the current entry to the school at 32 Otis, imagine something a bit grander. The building will be a 10-story podium platform with a 26-story tower. This plan was approved in 2016, so expect these buildings to be bound to fall any day now.

The Civic Center Hotel looking southeast from Market Street near 12th Street.

Photo: LisaRuth Elliott

Stop 5: The Civic Center Hotel and Plumbers Union Building, 12th and Market Streets

With this stop, we begin a long last leg of the Bound to Fall tour, with a mix of development plans that combine attempts at historic preservation, with gentrification of vintage (i.e. derelict) Single Room Occupancy (SRO) hotel sites and sporadic new demolition/construction that takes advantage of the City’s willingness to allow taller buildings in return for allocations of somewhat more affordable housing units.

This is the notorious Civic Center Hotel, well known to San Francisco police as the single most called in site in the city during 2014: more than 50 times. The San Francisco Plumbers Union (across the parking lot to the west) is expected to invest over $300 million for a “transformative” redevelopment project that would bring almost 600-new residential units and convert the Civic Center Hotel to higher standards for formerly homeless citizens. Almost the whole block from 1621 to 1637 Market Street will be demolished and replaced with six new structures. The Lesser Brothers façade and the Civic Center Hotel will remain as vintage reminders, helping to give context to an open plaza where a subway ventilation shaft will become a piece of public art.

The Miramar Apartments, Market Street at Page and Gough Streets.

Photo: LisaRuth Elliott

Look across Market Street to a somewhat better endowed brick building, the 1911 Miramar Apartments, that leads us into a discussion of one of San Francisco’s unique attempts at historic preservation: the Discontiguous Market Street Masonry District, or the Brick and Mortar Heart of the Hub. The Miramar, originally the Raymond Apartments, was designed in 1911 by noted architect G. Albert Landsburgh who also built some of the great movie/theatrical palaces that lined Market Street. Survivors include the Warfield and Orpheum theaters. The Miramar was also site of one of San Francisco's earliest social service outreach to the AIDS community in the early 1980s, giving housing space to people who at the time were considered pariahs.

Buildings in the Market Street Brick and Mortar historic district.

Photo: LisaRuth Elliott

Stop 6: Corner of Franklin and Market Streets

From this corner, you can see 8 living examples of brick and masonry artistry, raging in dates from 1911 to 1925. Designed by some of the City’s most prominent architects, these buildings are fabulous survivors of the post-earthquake era that defined San Francisco confluence of styles and were prominent gateways into downtown as part of this transportation hub.

Looking up Franklin Street to Fell Street (past the previously noted French International School proposal site), at 150 Franklin Street there is a Classic Revival apartment designed in 1912 by August Nordin who designed over 300 buildings, including the Swedish American Hall further west on Market Street. The trim features diamond-shaped white brick motif with a blue patterned border at eye level in a pattern known as “Greek Key”.

Just across the street from this member of the history club, are two other less illustrative buildings: the brown former San Francisco Unified School District building (across from The SFJazz Center, now featuring photos of jazz performers in the windows), and a former piano store turned office and residence, that has wooden keyboard design along the upper trim. The black keys have been whitewashed.

Look up: Classic Revival and Masonry features in terracotta forms above.

Photo: LisaRuth Elliott

The row of one story storefronts that corner Brady Street will have residential additions above. Across what is now a parking lot (that will be entryway to the public plaza), the corner building at 1649-1651 Market Street was built in 1912 as the Crockett Apartments, later Bradmar Apartments. It has interesting Classical Revival influences and Masonry facial features above designed by George Applegarth. Note the terracotta forms high above.

Next door is the 1911 Ascot Hotel at 1657 Market Street, an example of Venetian Gothic Revival style from the Hladik and Thayer design firm. It was built for a soap company, then a plumbing supply company.

Zuni on Market Street next to the Edwardian Hotel.

Photo: LisaRuth Elliott

Across Market Street, look to the Colonial Revival style of the Edwardian Hotel. It was designed in 1913 by William Crim. Note the fan-design windows.

72 Gough Street.

Photo: LisaRuth Elliott

Stop 7: Gough Street intersection

These two buildings don’t exactly fit the brick and mason mold, but have some elements: 72 Gough Street on the corner has brown bricks and rounded bay windows that add a distinct San Francisco character.

The Gaffney Building at 1670 Market Street.

Photo: LisaRuth Elliott

The Gaffney Building at 1670 Market Street is an early example of reinforced concrete and stucco from 1923 by Walter Falch. Note the smoked green glass windows above the Green Arcade bookstore window fronts. This was the Hub Tavern location, and potentially also where the Hub Market extended to from 1923 into about the 1960s. The Hub Market included a functional abattoir which specialized in veal.

McRoskey Mattress Store at 1687 Market Street.

Photo: LisaRuth Elliott

Even grander is the Edward McRoskey Mattress store, a wonderful wedding cake Classical Revival building from 1925. It is one of the historic anchors of the Hub district, bringing the gilded Jazz Age into the 21st century. As of late 2018, McRoskey Mattress has sold the brand and the mattresses are being manufactured elsewhere. This building is still owned by the McRoskey family and will continue to function as a showroom.

The Allen Hotel at 1695 Market Street, also former site of DeLessio Market.

Photo: LisaRuth Elliott

The 1914 Allen Hotel (originally the Hotel Fallon) has been home to several ground level cafes is a Renaissance Revival with castle-like features along the rooftop and a center flagpole that make it a unique contributor to the area. Architect Conrad Meussdorffer was considered an extremely important San Francisco designer.

These are some of the survivors of change. Nick’s Foods and Deli at 1659 Market Street is holding out and keeping its store clean of health code violations. How long can it last? The Fast Frame on the corner is already vacated and bound to fall [It was demolished in late 2018-ed.] The former home of Michael’s Octavia Lounge, the Alano Club, and Lyon Martin Health Care is also mostly boarded up and bound to fall.

The unmistakable wooden figure of Flax Art & Design.

Photo: Arthur O'Donnell

The site of Flax Art & Design store, a San Francisco icon, is already gone. These will become 8 to 12 story mixed use buildings offering only rentals, and some won’t offer off-street parking. A safe manufacturing company which operated at this site still owns the land.

San Francisco Community College District building at 33 Gough Street.

Photo: LisaRuth Elliott

Down the block, the Community College administration building at 33 Gough Street, is intended to give way to as many as 433 residential units in a 23-story tower, with a high percentage of below-market priced apartments as part of the HOME-SF program.

See more on the historic Hub Neighborhood.

Read about the historic district, The Market Street Hub Neighborhood, as seen on The Green Arcade Bookstore's site.