The Prison Ship 'Euphemia'

Historical Essay

based on an article by James P. Delgado

The Euphemia

Image: The Annals of San Francisco, 1855

The discovery of gold in California during the early days of 1848 provoked, in the quest for fast and easy fortune, a mass migration to California that has been termed the greatest movement of humanity since the crusades. By early 1849, hundreds of vessels cleared from various ports, their destination California. California was soon host to thousands of eager gold seekers from all parts of the globe. San Francisco, being located at the entrance to the great San Francisco Bay, found itself to be the gateway to the gold fields. The effect was instant: from a tiny settlement half hidden by sand dunes, it became ... a Venice built of pine instead of marble ... a city of ships, piers and tides.

The streets of San Francisco were crowded with thousands of argonauts. Mingling with them, and attempting to remain anonymous in the chaotic conditions of the excited Gold Rush days, were various criminals. The rough and ready life, the lack of government or of the powerful enforcement of law, and the intoxicating influence of gold proved to be inducements to criminal activity. San Francisco was daily the scene of murder, robbery, assault and arson. As San Francisco became a more settled and established town, the reaction of the populace to criminal activity became increasingly hostile. The final outrage to many was the assault by an organized group known as the Hounds against the San Francisco Chilean community on July 15, 1849. In the aftermath of this bloody event, San Francisco organized to drive out the Hounds and press for an effective police force and a stronger jail.

San Francisco's first jail was an outdated and flimsy log structure built around 1846 at Clay and Stockton Streets. Early San Francisco resident John Henry Brown recalled in later days, just how flimsy the jail, or calaboose, was:

One night a man, by name of Pete, from Oregon, was put in the Calaboose, for having cut the hair off the tails of five horses and shaved the stumps. As Leavensworth (the Alcalde) did not send him his breakfast, he called on Leavensworth at his office, with the door of the Calaboose on his back, and told him if his breakfast was not sent up in half an hour we would take French leave. Leavensworth sent his breakfast ....

The Town Council of San Francisco realized how insecure their jail was, and following the Hounds incident they began to search for a new jail. A special committee was appointed to either purchase or lease a new building for the jail. A particular dilemma faced the committee; the inflated gold prices of San Francisco had driven up the costs of building, hence rents were also high. A possible solution, and a thrifty one, was the use of an abandoned ship for a building. Gold fever had also stricken the crews of the vessels that had brought the argonauts to California, and hundreds of ships lay empty along the waterfront. The solution for the special committees dilemma was at hand; they purchased a ship for use as San Francisco's new jail.

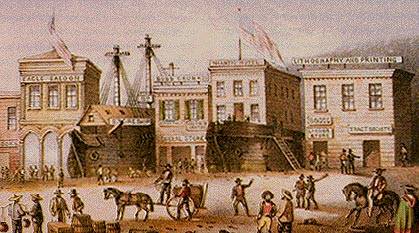

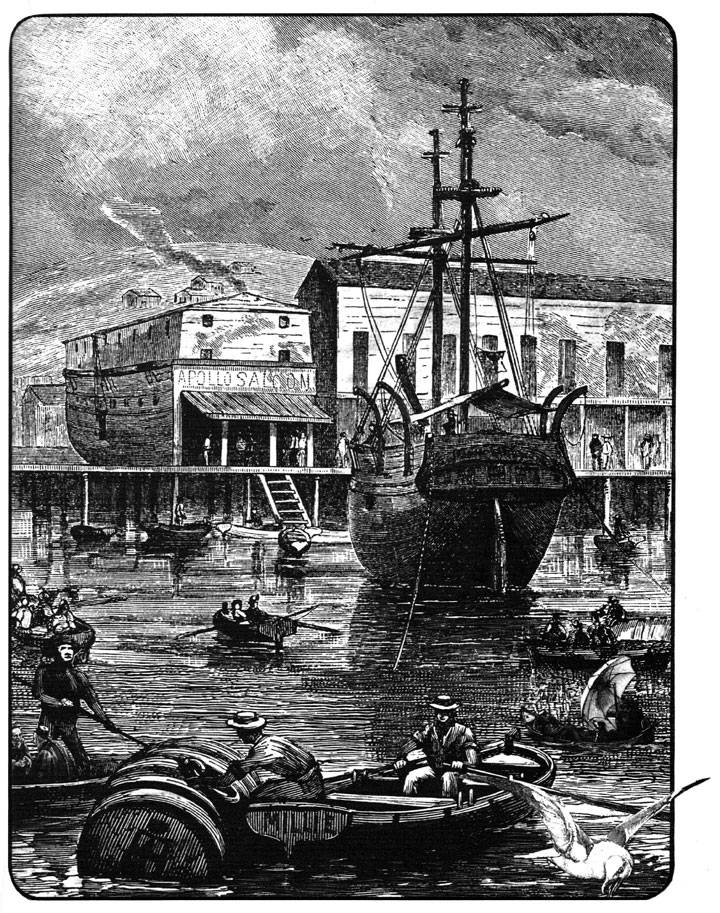

Ships converted into buildings played an important role in Gold Rush San Francisco. In addition to the prison ship, there was a ship converted into a church, and other vessels such as the famous Niantic and Apollo, had been converted into warehouses, hotels and offices.

The Apollo (left) and Niantic on San Francisco's 1850 waterfront.

At the October 8, 1849 meeting of the Town Council of San Francisco, the special committee reported the purchase of the brig Euphemia for the purpose of a prison ship. The former owner of the Euphemia, incidentally, was Town Council member William Heath Davis. The purchase price: three thousand, five hundred dollars.

The Euphemia was berthed next to the Central Wharf and work was begun to convert her into a prison ship. Most probably the area below the decks was converted into a cell block, while the cabin above deck must have served as the guardhouse. On December 10, 1849, at the Town Council meeting Messrs. Brannan, Davis and Post reported the satisfactory conversion of the ship into a prison. The work had required some $1,033.75 worth of lumber. The balls and chains arrived in late January of 1850 at the cost of $523.80. Not counting labor costs, the new jail had cost San Francisco $5,357.55 not bad considering a simple one-story house of clapboard and shingles cost approximately $15,000 to build at that time.

At her berth on Central Wharf, the Euphemia was in the heart of the rapidly expanding city. New construction constantly pushed the city limits out into San Francisco Bay, finally overrunning the Euphemia and her storeship neighbors, the Niantic and the Apollo. With the nearby streets and buildings raised on piles above the shallow waters of the bay, and hemmed in by the construction around her, the Euphemia lay quietly in the stagnant waters of the San Francisco waterfront, never to go to sea again. It was the end of a long career that had probably begun sometime around 1800 in the British Isles. Built as a brig, or a small two-masted vessel, the Euphemia was about ninety feet long and was registered at 137 tons.

By February 1, 1850, the Euphemia was receiving prisoners. In addition to any criminals apprehended the new prison ship also held any suspicious, insane or forlorn persons found strolling about the city at night the Euphemia thus became California's first formal insane asylum. That first year twelve persons adjudged to be insane were locked in her hold. In later years the San Francisco Alta California recalled that the Euphemia had housed over and furnished quarters to many of the poor unfortunates ...

The prisoners on board the Euphemia earned their keep by toiling at public works while on a chain-gang. During the day they would labor on shore and return at night to the ship. Conditions on board were undoubtedly less than desirable. While there is no account of life on board the Euphemia, a comparison may be fairly drawn from a description of life on board the Waban, a prison ship used by the State of California on San Francisco Bay in 1853:

At night they were locked below, four or five men to each eight foot square compartment. During the warm summer days they stewed in their own juices, while in the rainy winter they stayed below day after dreary day. In the mornings the effluvia of feces and sweat and general decay was so strong the guards refused to go below until the lower decks had been aired out ...

Collage depicting Apollo Saloon and Euphemia by Satty, from "Visions of Frisco" edited by Walter Medeiros, Regent Press 2007

Conditions on board the Euphemia worsened throughout 1850 as more prisoners were locked in her hold. As early as August 4, 1850, the Alta California noted that:

Our attention has been recently called to the condition of prison discipline in this city. The brig and the stationhouses are literally filled with prisoners, and we recently heard one of our city functionaries express the opinion that if any more were incarcerated these places would rival the famous black-hole of Calcutta. As it is, six or eight men are crowded into a single cell, scarcely large enough for one man's accommodation. It has been recommended that another brig be purchased to relieve the crowded state of our prison houses ... and it is hoped that the city council will take the matter in hand immediately.

The city of San Francisco eventually began construction of a larger prison, which was completed in mid-1851.

The eventual fate of the Euphemia is unknown. Local legend insists that she was seized by a creditor of the city in payment of a debt. There is no record, however, to substantiate this claim. Most probably as the city grew, and the location at which she was anchored became thoroughly boxed in by streets and buildings, the Euphemia was scuttled where she lay in order to make way for land fill and a building on the site.

Most probably, the Euphemia was stripped of her upper works and all usable fittings by one of San Francisco's many marine salvage firms of Gold Rush days. Then her bare bones would have allowed to slowly settle into the shallow water and mud, to be covered with debris and sand as the city filled over the old waterfront. The remains of the Euphemia then lay forgotten and buried as San Francisco grew and expanded over the years. Several buildings marked the site of the old ship, the last being razed in 1920 to make way for the construction of the new headquarters building of the federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

The January 15, 1921, edition of the San Francisco Chronicle announced the re-discovery of the Euphemia with the headline EXCAVATION BARES CITY'S EARLY-DAY PRISON SHIP: HISTORIC BRIG UNCOVERED AT DOWNTOWN CORNER. The newspaper reported:

Under the mud and silt dug out by steam shovels at the corner of Battery and Sacramento streets, the remains of San Francisco's first jail are being brought to light ... the Euphemia was buried under the creeping silt until the excavation ... disclosed her lying some thirty feet below street level.

In later years, former San Francisco Chronicle reporter William Martin Camp recalled the discovery of the ship:

... the new bank building needed an especially deep foundation, and the steam shovel had worked its way to a considerable depth when it struck a snag. Workmen tried every means of removing the obstacle before they discovered they were digging into the stem piece of a ship. They went to work with pick and shovel and finally uncovered the entire keel and a considerable part of the planking and flooring of the ship.

This story came from Walter MacArthur, a Glasgow sailor who for many years was the United States Shipping Commissioner of San Francisco. Captain MacArthur, an authority on ships, examined the hull and identified it as the remains of the brig Euphemia, built in England, a pioneer vessel which ended her days as a prison ship anchored in the cove. The discovery sent a thrill through the scores of idle watchers who stood around the protective railing surrounding the excavation ...

Despite MacArthur's identification of the remains, some have thought that the ship uncovered was the storeship Apollo, which had been located to the west of the Euphemia. However, in 1925, work at the northwest corner of Battery and Sacramento streets, in the rear of the new Federal Reserve Bank, discovered the stern of the Apollo. Only about eight feet of the Apollo was uncovered in that excavation and no more.

The discovery of the Euphemia and of her neighbor, the Apollo, thrilled San Francisco much in the same way the discovery of the old Niantic in April of 1978 captivated the imagination of the city, and constituted a powerful reminder of history's importance in the process of urban decay and regeneration.

-- based on an article by James P. Delgado, California History magazine, Fall 1978