Father Peter C. Yorke, Labor Champion

Historical Essay

by Chris Carlsson

Father Peter C. Yorke

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Father Peter C. Yorke had an enormous influence on politics and especially the labor movement in San Francisco at the turn of the 19th to the 20th century. He rose to prominence in the 1890s when he became the leading Catholic voice repudiating the American Protective Association (A.P.A.), an organization formed to attack the Catholic presence in the United States. Given today’s scandalous revelations about the Church’s ongoing role in protecting child abusers, it’s easy to support an anti-Catholic point of view, but in the 1890s, the effort was led by aggressive Protestant ministers and businessmen who sought to augment the existing domination of White Anglo-Saxon Protestant (WASP) society over the supposedly inferior populations who, in San Francisco at least, were mostly Catholic (predominantly Irish and Italian, with some Mexican and others from South and Central America).

A bitter fight over a school textbook began the public fight in 1893, which corresponded to an ongoing national debate over the role of public vs. parochial schools. For Catholics, the separation of Church and State had driven them to found their own schools, but of course the implicit teaching of Protestant Christianity in the public schools went on anyway. During a time of heightened religious sectarianism in the late 19th century, many Protestants were not content with coexistence with Catholics but actively sought to challenge and undermine Catholic teaching at every opportunity, apparently up to and including manufacturing fake quotes from supposed Catholic documents to “prove” that Catholic priests would not obey civil law but only the Pope. One of the forgeries that gained traction in San Francisco thanks to promotion in the San Francisco Chronicle at the time was an encyclical attributed to Leo XIII which called upon Catholics to rise in bloody revolution on or about the feast of St. Ignatius Loyola, 1894, at which time a Catholic congress would convene in Chicago to hand the country over to the pope! (1)

Already many local employers, supporters of the A.P.A. at the outset, had promised not to hire Catholics. On September 5, 1894, Irving M. Scott, the superintendent of the Union Iron Works, publicly declared that “no Roman Catholic would receive employment from him in the future when a Protestant could be secured.” Father Yorke met the challenge head-on in a series of contentious articles in the daily press, but going further, he began to call out the A.P.A. for what it really was, an organization dedicated to disrupting labor solidarity as much as attacking Catholicism.

Again and again he urged the forces of labor to recognize the fact that at bottom the American Protective Association was anti-labor as well as anti-Catholic. “ ‘I will not enter into an agreement with a Roman Catholic to strike,’ “ he wrote. “This is a part of the A.P.A. oath. In whose smithy,” asked Yorke, “was it forged, Monopoly’s or the devil’s?” (2)

Through his essays and public speeches, Father Yorke rose to prominence among San Francisco Catholics. As the priest at St. Peter’s he anchored a strong Irish Catholic community on 24th Street in the Mission for many years. From his pulpit he frequently spoke out on issues facing the working class, following closely the teachings of the Pope’s 1891 encyclical Rerum Novarum that emphatically defended the rights of workers against exploitation and the injustice created by extremes of wealth and poverty. Much to the dismay of wealthy Catholic businessmen, Father Yorke waded into bitter strikes on several key occasions in the early 20th century.

In 1901, the City Front Federation, responding to a dispute between the Teamsters and a non-union delivery service, called the members of its dozen constituent unions out on strike. All workers on the docks including four different longshoremen unions, packinghouse workers, and teamsters were on strike together demanding that the existing agreement between the Teamsters and the Drayman’s Association providing for unionized labor only be respected. What became clear during the strike was that a new secretive organization called the Employers' Association had ordered the delivery company to provoke the strike in service to their larger campaign to break the union movement.

When Yorke realized that the dispute was over the basic issue of unionism itself he wrote, “The Pope says that the principle of unionism is good. The Employers’ Association says the principle of unionism is bad.” He saw it as a question of rich versus poor, declaring “Why do the rich men organize to destroy the organizations of the poor man? Because the rich men are opposed to unions; they don’t believe that the poor man should organize.” (3) The strike erupted in early May and within weeks dozens of other unions were on strike too, from laundry workers to iron workers across the City. The Employers’ Association had put aside a large strike fund and was determined to break the unions, but strikers maintained solidarity through the summer.

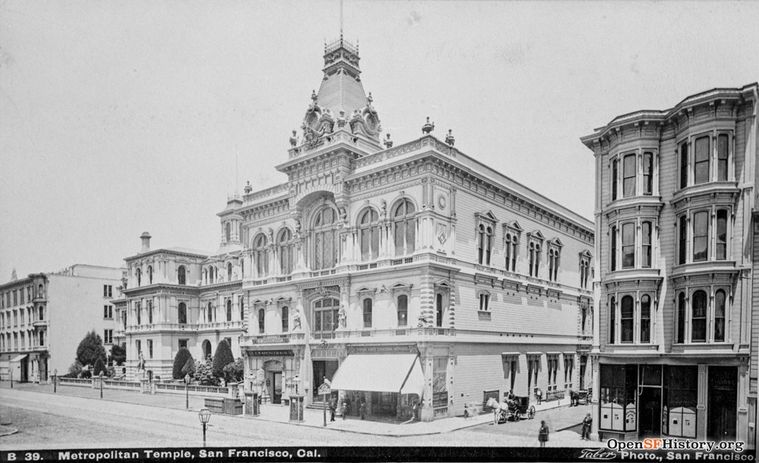

Metropolitan Temple, site of Father Yorke's 1901 speeches, on 5th Street and Jessie, just south of Market.

Photo: courtesy OpenSFHistory.org

In early August, Yorke gave a fiery speech at the Metropolitan Temple on 5th Street between Market and Jessie in which he ridiculed the Employers’ Association: “...where there is unity there is strength. The employer who will turn his back on one man will think ten times before he offends 500 men. Therefore, there is more of a chance of a man getting his rights, if it is the voice of the union that speaks instead of the voice of a single man.” (4) Six weeks later, on September 21 he spoke to a throng of 15,000 people at the Temple, defending the principle of unionism. He concluded by saying that all workers had an obligation to join an honest union for the mutual protection of their rights.

Meanwhile, Mayor James Phelan, a Catholic himself who had won election as a Democrat in 1896 after Yorke’s successful takedown of the American Protection Association’s Catholic scapegoating campaign, sided entirely with the Employers’ Association. After repeatedly sending police to attack strikers and defend violent strikebreakers, he was quoted in the press saying “If they don’t want to be clubbed, let them go back to work.” The press were pushing the owners’ side, and Yorke was soon blamed for altercations by Police Chief Sullivan. As it happened, California Governor George Gage, a long-time friend of Father Yorke, finally intervened in the strike on October 2 and forced a settlement by excluding the Employers’ Association from further negotiations. Conditions returned to the status quo before the strike with unions in control of many workplaces in San Francisco and union contracts reaffirmed by business owners. The Employers’ Association dissolved within a year, having failed to do the one thing it was set up to do: destroy San Francisco’s unions.

In 1906, just a few months after the devastating earthquake and fire, the streetcar workers known as Carmen voted to strike against the privately owned United Railroads, owned by Patrick Calhoun. The City government was still run by the Union Labor Party who had swept into office in the wake of the 1901 City Front strike when Democratic Mayor Phelan had unleashed the police on strikers. Mayor Eugene Schmitz refused to authorize police to protect strikebreakers for the United Railroads and Father Peter Yorke publicly came to the defense of the workers:

“Strikes follow labor organization as logically and inevitably as battles follow military organizations… Organized labor and organized capital are two great armies. When the leaders of both disagree war is declared by either, and a strike is on. This is a bad method, perhaps, but on the side of labor at least it is the only method that has so far been effective… The suffering and misery caused by strikes are necessary losses of battle; the gain very much more than balances the account, and it is permanent.” (5)

As it turned out this strike ended badly for the Carmen. After being on strike for months, and dozens of deaths and injuries on the streetcars (including a horrifying barrage of gunfire from hired goons that killed five on the first day of the strike), the strike gradually crumbled. By March of 1908 the Carmen turned in their charter and dissolved their union! In spite of strong support from the public and Father Yorke during the long months on strike, the intransigence of Calhoun eventually defeated the union.

Father Peter Yorke's grave at Holy Cross Cemetery in Colma, California.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Father Yorke continued to be a powerful force in San Francisco during the following years, anchoring the Irish Catholic community in the Mission. He is now buried at Holy Cross cemetery in Colma. His role at St. Peter’s reverberated through the decades, and it wasn’t until the early 1960s when the Irish Catholics of the Mission finally gave way to the new wave of Latino immigrants who were reshaping the neighborhood. Spanish language masses were introduced in the early 1960s; even though the demographics of the parish changed, St. Peter’s remained active in defense of the poor throughout its history, engaging in housing, immigration, and other crucial campaigns over the years.