Nihonjin-Machi, San Francisco's Japanese People Town

Historical Essay

by Alison Jordan

San Francisco’s Japantowns, 1880-present

Map: Ben Pease

| The history of Japanese immigrants in San Francisco has been reflected in their evolving physical spaces. The original Japantown, or Nihonjin-Machi, was found South of Market in the Stevenson/Jessie Streets area. There, Japanese immigrants created a thriving cultural and economic hub in the constrained space they were permitted to inhabit. Nihonjin-Machi was devastated by the earthquake and fire of 1906, which led the Japanese community to relocate to the present Japantown in the Western Addition. |

The first Japanese immigrants came to San Francisco, or "Soko" as they called it, in 1869. Originally, these immigrants were predominately young men searching for new economic opportunities. In 1868, the pro-modernization Meiji government of Japan enacted a new land-tax system that negatively impacted farmers. In the following decades, about 367,000 farmers lost their land to these high tax rates, inspiring them to seek other opportunities abroad (Raichel, 7). In 1870, the first Japanese Consulate in the United States was established in San Francisco. According to that year’s U.S. Census, there were only 55 Japanese in the United States, 33 of which were in California. This number increased slightly in the succeeding decade to 86 Japanese in California, 148 nationally. However, Japan relaxed emigration regulations in the 1880s, which led to a boon of new arrivals. By 1890, there were 1,114 Japanese in California (Page & Turnbull, Inc. San Francisco Japantown Historic Context Statement). This number grew massively when the Organic Law of 1900 voided the contracts of all Japanese working in Hawaii, which enabled many to seek opportunity on the mainland, particularly in the American West. The Immigration Commission calculated that there were 79,000 Japanese immigrants in the United States in 1909 (Raichel, 7). San Francisco, as the chief port of entry for Asian immigration, had the largest Nikkei, or Japanese emigrant, population of any mainland American city (San Francisco Japantown History+Index).

The early Japanese immigrants settled in Chinatown. According to a San Francisco Planning report, this co-location of Asian immigrants occurred across the Western United States during this time period. Both the Chinese and Japanese immigrant communities shared a history of stringent immigration policies, restrictions on land ownership, discrimination, and status as non-citizens. Chinese immigrants had "pioneered many of the occupations and neighborhoods in which Japanese immigrants later settled" (Page & Turnbull, Inc. San Francisco Japantown Historic Context Statement). These neighborhoods were often the only places that permitted Japanese immigrants to live and set up businesses. General xenophobia was exacerbated by the turn of the century, with Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese war in 1905, and the fears of Japanese military power this brought, as well as the economic rivalry between Japanese immigrants and the white community (San Francisco Japantown History+Index).

Despite the discrimination, overt and covert, the Japanese faced in establishing lives in San Francisco, they were able to create physical community. The original settlement in Chinatown was expanded in 1900, as Japanese immigrants began to congregate in the South-of-Market area, along Jessie and Stevenson streets, between 5th and 7th streets. It was here that the first Japantown was established, and thrived, until its destruction by the 1906 earthquake. The South of Market Japantown was the basis of Japanese settlement in the mainland United States, the home of a community and culture that played an essential part in shaping San Francisco’s evolution through the turn of the century.

South of Market Historical Context

The area South of Market was established as an immigrant and working-class district during the 1870s–1880s. By 1879, San Francisco itself had the highest percentage of foreign-born residents of any major American city. The majority of immigrants at this time were Irish: In 1880, one third of all city residents were Irish. This number was even higher in South of Market, where those of Irish descent constituted half of the population. The architecture of the South of Market area reflected the high demographic of immigrant workers—during the 1870s, it held one-quarter of all the boarding houses and half of the lodging houses in the city (Page & Turnbull, Inc. Historic Context Statement: South of Market Area, San Francisco). These lodging houses were incredibly crowded and dirty: One Japanese immigrant described the condition of one’s kitchen, saying, "There were no stoves as the boarding houses had…all cooking was done on one or two burner oil stoves… Thick, black smoke darkened the rooms, and we were oblivious to the odor which assaulted our nostrils" (Johung, 138). Due to its status as an immigrant district, South of Market was free from the racial covenants that discriminated against Japanese that were common in other areas of the city. The Japanese capitalized on this limited amount of space available to them by establishing their own cultural and physical enclave.

South of Market Nihonjin-Machi

While the Issei (first-generation Japanese immigrants) settled in Chinatown along Dupont between California and Bush Streets, following waves of immigrants began to colonize the South of Market area. The amount of Japanese in San Francisco jumped from 590 in 1890 to 1,781 in 1900 (Dillingham). In the new South of Market colony, they established exclusively Japanese rooming houses and small businesses. The majority of Japanese establishments were actually located on back alleys, on Stevenson and Jessie streets (Page & Turnbull, Inc. San Francisco Japantown Historic Context Statement). This area was the first to be called Nihonjin-Machi, or Japanese People Town, by its inhabitants—a different meaning than the term used by outsiders, Nihonmachi, which translates directly to Japantown. One resident commented on this distinction:

The Japanese in those days did not call themselves, in English, Japantown. Before the wars, from time to time I would say “Japantown” because the majority of the people started saying that see; but I insisted on saying it was “Japanese Town…” The reason for this is that Japanese people are a very sensitive people, as a whole, very sensitive compared to others. (Laguerre, 5)

This resident was referring to the fact that outsiders’ use of Japantown was meant to emphasize the section’s inferior status, while the reference to “Japanese People” by the inhabitants was a form of empowerment through group identification. He also did not want to give the impression that the Japanese were colonizing a part of America, especially during this period as Japan grew in its military power through its victories in the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) and Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905) (Raichel, 8).

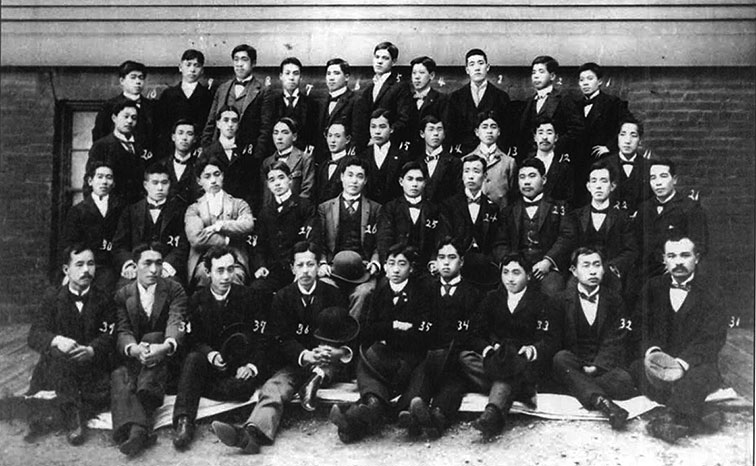

An 1898 young men's kenjin-kai, or social group

Photo: California Historical Society

In Nihonjin-Machi, numerous social, economic, and political organizations expressly for the Japanese were established. This included several churches, such as Japanese Methodist Episcopal Church and Japanese Buddhist Mission, as well as civic organizations like the Japanese YMCA and T. Honda Employment Agency. Nihonjin-Machi provided a safe area for which Japanese had the opportunity to set up their own independent businesses, an opportunity that was generally denied outside of this enclave (Raichel, 7). In Nihonjin-Machi, there were entertainment sites like pool halls as well as banks, shoe repairs, restaurants, photo studios, hotels, laundries, dental offices, midwives, etc. all owned by the Japanese residents. The general stores stocked items that the Japanese desired from home and were not carried by traditional white grocers. There were several businesses rooted in Nihonjin-Machi by necessity: There was a prevalence of Japanese barber shops, as Japanese traditionally were not admitted to white barber shops. The same rule applied to bathhouses and hotels. The Japanese Shoemaker’s even established their own union in 1893 as they were unwelcome in the majority of traditional worker’s unions at the time (Dillingham).

However, there was a thriving business venture that catered to predominately white patrons. The Arts Goods stores were devoted to selling Asian artifacts such as brass ware, toys, china, and more to practically all white San Franciscans. The "oriental" exoticism of these goods was very popular in wealthy San Francisco homes at the turn of the century. To reflect this trend, stores carried stocks of goods valued at several thousand dollars (Dillingham). Yet the source of economic competition that caused friction with the white community was, as with the Chinese, the laundries, which were also openly boycotted. The economic competition of the Japanese was a topic of such scrutiny that it was actually explored in a federal report a few years later, in the 1911 Dillingham Report prepared by the U.S. Immigration Commission, Immigrants in Industries: Part 23: Japanese and other Immigrant Races in the Pacific and Rocky Mountain States Report to the 61st Congress. Regardless, the majority of businesses catered exclusively to the Japanese residents of Nihonjin-Machi, and created a community in which these immigrants were welcome and had their own established institutions, to help create a new life in San Francisco despite friction with other groups.

Movement of Japantown: 1906 Earthquake

The South of Market area was destroyed by the 1906 earthquake and succeeding fires. The section was built on extensive filled ground that was essentially liquefied through the tremors. Eleven fires erupted in the area from broken gas mains, and quickly grew out of control by feeding on the densely packed wooden boarding houses. As the water mains were broken the firefighters were unable to curb the flames. The neighborhood was practically gone within six hours of the earthquake. The death toll in South of Market was significantly higher than in the rest of the city due to this combination of factors (Page & Turnbull, Inc. Historic Context Statement: South of Market Area, San Francisco). Nihonjin-Machi was devastated. Dave Tatsuno recalls the earthquake experience of his father, Shojiro Tatsuno, a Japanese immigrant with his own dry goods store, Nichi Bei Bussan, in Chinatown:

When the 1906 earthquake struck around 5 a.m., Shojiro was living next to a tall brick firehouse. The firehouse collapsed away from him and crushed the other house, killing everyone inside. If it had collapsed toward him, he would have been killed and there would be no history of Nichi Bei Bussan or the Tatsuno family thereafter. We can be very thankful. (Seigal, 8)

Even with this destruction came opportunity for the Japanese immigrant community. The majority of those who had previously inhabited South of Market relocated to the Western Addition, which was left relatively intact after the quake. All the main government and commercial services were shifted to this area in the time directly following the disaster. South of Market and Downtown were rebuilt as commercial and industrial properties, displacing the previous working-class community. The Western Addition came to be known as San Francisco’s "Little United Nations" due to its large immigrant population (Page & Turnbull, Inc. San Francisco Japantown Historic Context). This is where Japantown is still located today. It has faced its own attacks, including the relocation of its entire population during World War II’s Japanese internment. However, it has survived as a cultural enclave as one of only three remaining Japantowns in the United States today.

Despite being classified as "aliens ineligible for citizenship," the Japanese were able to create physical space for themselves in San Francisco. They faced much discrimination but were able to carve a section for the city out for themselves, starting in South of Market and transferring to the Western Addition after the 1906 earthquake. These spaces were important to retaining their culture, as well as creating institutions for their new lives in San Francisco. In line with this sentiment, the San Francisco Planning Commission, Historic Preservation Commission, and Board of Supervisors unanimously adopted resolutions in support of the Japantown Cultural Heritage and Economic Sustainability Strategy (JCHESS), to preserve the history of the Western Addition Japantown (Japantown Cultural Heritage and Economic Sustainability Strategy). And yet, the original South of Market Nihonjin-Machi enclave has been all but forgotten; there are no monuments or plaques where these businesses and residences once played a vital part in the Nikkei experience. The long history of Japanese immigration, starting in the 1870s, has been almost overshadowed by later anti-Japanese developments in the 1900s, such as the segregation of San Francisco public schools and Japanese internment during World War II. This physical space that the Japanese created, though destroyed through earthquake and fire, was their home. Their presence in the South of Market area is an important chapter in the long legacy of the Japanese experience in San Francisco, and one that was the building blocks for further Japanese immigration to and influence on the development of the City.

Sources

Dillingham, William Paul. Reports of the Immigration Commission: Immigrants in Industries, Part 25: Japanese and Other Immigrant Races in the Pacific and Rocky Mountain States Report to the 61st Congress. Rep. Vol. 85. N.p.: United States Immigration Commission, 1910. Part 1.

"Japantown Cultural Heritage and Economic Sustainability Strategy (JCHESS)." City and County of San Francisco Planning Department, 2013. Accessed March 2, 2017.

"The History of Japantown." Discover San Francisco Japantown! Japan Center Garage Corporation, 2014. Accessed March 3, 2017.

The Japantown Taskforce, Inc. "DEFINING CULTURAL PRESERVATION." Japantown Taskforce, 2009. Accessed March 3, 2017.

The Japantown Taskforce, Inc. Images of America: San Francisco's Japantown. Charleston: Arcadia, 2005.

Johung, Jennifer, and Arijit Sen. Landscapes of Mobility: Culture, Politics, and Placemaking. N.p.: Ashgate Group, 2013.

Laguerre, Michel S. The Global Ethnopolis: Chinatown, Japantown and Manilatown in American Society. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2002.

Page & Turnbull, Inc. "Historic Context Statement: South of Market Area, San Francisco." City and County of San Francisco Planning Department, 30 June 2009. Accessed February 27, 2017.

Page & Turnbull, Inc. San Francisco Japantown Historic Context Statement. Historic Context Statement. The San Francisco Planning Department as Part of the Japantown Better Neighborhood Plan, May 2009. Web. 26 Feb. 2017.

Raichel, Daniel, Lynn Harada, and Esther Hurh. "The Journey from Gold Mountain: The Asian American Experience." (n.d.): n. pag. Japanese American Citizens League, 2006. Accessed March 18, 2017.

San Francisco's Japantown. Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2005.

"San Francisco Japantown History+Index." Japantown Atlas - San Francisco Japantowns. Japantown Atlas, 04 Aug. 2007. March 1, 2017.

Seigel, Shizue, ed. Standing Strong! Fillmore & Japantown: Voices from Write Now! Fillmore and Write Now! Japantown. San Francisco: Pease Press, 2016.

|

|

|---|---|

| Hotels | Art Goods Stores |

| *Hinode Ryokan *Okayama Ryokan *Chikushi-Kan *Fujiyama-Kan *Kishu-Ya *Nankai-Ya *Kinokuni-Ya *Iqusa *Yamada Ryokan *Kyokan *Shikoku-Ya Ryokan *Tokyo Ryokan *Yoshino-Ya *Ichigo-Ya *Toyo Ryokan *Oiso-Ya *Meiji Hotel *Teikoku Hotel *Maruichi Ryokan *Fukuoka-Ya *Sanyo Ryokan *Yanai-Ya *Geishu-Ya *Boshu-Ya *Iki Shiranuhi Ryokan *Kumamoto-Ya *Kohsa-Ya *Nikko-Ro *Hinomatu-Tei *Tamura Ryokan *Hiroshima-Ya *Baba Ryokan | *Kisen Shokai *Toyo Shokai *Matsushita Shokai *Kobe Shokai *Yamato Shokai *Meiji Shokai *Kisen Shokai *Asahi Shokai *Yamanashi Shokai *Azuma Shokai *Hinomoto Shokai *Mizuhara Shokai *Tombo Shokai *Shiota Shokai *Tomono Shokai *Ashikaga Shokai *Mikida Shokai *Yamato Shokai *Shibata Shokai *Kai Shokai |

| Restaurants | Shoe Repair Shops |

| *New Kitchen *Suehiro *Hogyoku *Seiyoken *Fukusuke-Tei *Shungetsu-Tei *Daikoku-Ya *Kyokusho-An *Chiyoshi -Izutsu *Port Arthur *Meigetsu *New York *Grant *Toyo *Kinkai-Ro *Yanagi-Ya *Aoyagi *Star | *K. Nishimura *G. Uji *N. Tomoda *S. Tanji *G. Tanamuachi *Nakamura *Nobe *Takagi *M. Kiyota |

| General Merchandise Stores | Barbers |

| *Uyeda Shokai *Togasaki Shokai *Domoto Shokai *Asahi Shoten *Kurimura Shoten *Minegishi Shoten *Komada Shokai *Nippon Shokai *Kokusan-Sha *Nichi Bei Bussan *Tsumura Shoten *Hatano Shokai (Fuji Co.) *Ide Shoten | *Chiba-Doko *Hanamura-Doko *Nakagawa-Doko *Hamai-Doko *Kasahata-Doko *Murata-Doko *Ichigo-Doko *Sekishima-Doko *Segawa-Doko *Nakajima-Doko *Yokohama-Doko *Nakahori-Doko *Kuramoto-Doko *Shigeno-Doko |

| Churches and Organizations | Books and Stationers |

| *Nippon Club *Japanese Gospel Society (Fukuin-Kai) *Japanese YMCA *Japanese Buddhist Mission *Japanese M.E. Church South *Japanese M.E. Church *Ellen Stark Ford Home (Fujin Home) | *Aoki Taiseido *Chuo-po *Fuyo-Do *Kamiya Book Store *Y. Suito Books and Magazine Rentals |

| Shooting Galleries | Bathhouses |

| *Kiguchi *Hayashi *Watanabe *Tokikawa *Tsukazaki *Kearny | *Katayama-Yu *Kiwa-Yu *Sakura-Yu *Segawa-Yu *Suehiro-Yu *Tamura-Yu |

| Photo Studios | Confectioners |

| *Ishiguro *Motoyoshi *Misumi *Y. Miyagawa | *Osaka-Ya *Kameya *Asahi-Ya *Ishikawa Benkyodo |

| Employment Agencies | Pool Halls |

| *Fillmore *Hirano *T. Honda | *Asahi *Hinode *Takagi *Kuramoto *Matsumoto |

| Laundries | Banks |

| *Favorite *(Hatanaka) Tokyo | *Nichi Bei *Yokohama Specie |

| News | Miscellaneous |

| *New World (Shin-Sekai) *Japanese American News (Nichi Bei) | *Toyo Kisen Kaisha *Mitsui Bussan Kaisha *Kangyo-Sha *Mori Drug Store *Y. Araki (Mid-wife) *Masai Watch Repair Shop *Empire Shoe Company *Y. Miyoshi Dental Office *Suzukawa Express |