Emeryville Mudflat Sculptures

Historical Essay

by Lincoln Cushing, via Docspopuli

"Vandals destroy Central America art project"

—Marian Rust, S.F. Bay Guardian, April 15, 1987

reprinted in Community Murals, Summer, 1987

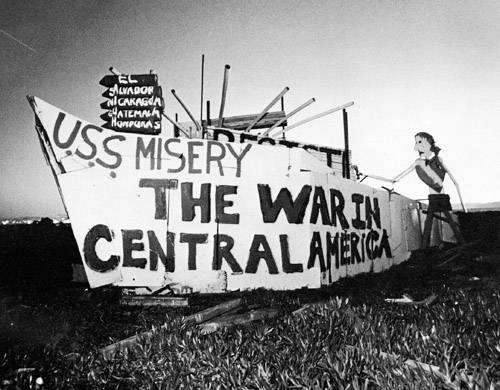

"Community sculpture protesting U.S. intervention in El Salvador arising from Emeryville mudflats, California freeway I-80." Community Murals, Fall, 1981

Photo: Marvin Collins

When 50 Bay Area artists erected six huge sculptures in the Emeryville mudflats to dramatize for commuters the war their tax dollars are financing in Central America, they didn't expect an entirely friendly reception. "One of the proofs that it's going to have an effect is that it won't last a week," artist Doug Minkler said April 5th, the afternoon the three-month project was completed.

Minkler's projection turned out to be optimistic. By dawn on April 6th, virtually all of the sculptures already had been demolished. No one has claimed responsibility for the vandalism, but several artists involved in the project speculate that the perpetrators were linked to the military.

<iframe width="100%" height="50" scrolling="no" frameborder="no" src="https://w.soundcloud.com/player/?url=https%3A//api.soundcloud.com/tracks/324339910&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&visual=true"></iframe>

East Bay Yesterday's half-hour podcast on the history of the mudflat sculptures.

Courtesy East Bay Yesteday

According to Scott Braley, one of the mudflat artists, the project aimed to underscore the Bay Area's role in determining U.S. military policy in Central America. The Bay Area is home not only to the Concord Naval Weapons Station and the Presidio Army Base, which coordinates the National Guard training exercises in Honduras, Braley told the Bay Guardian; the region is also a base for extensive illegal arms activity, linked to figures like Palo Alto resident Richard Secord and companies like the formerly CIA-owned Southern Air Transport.

The artists sought to show their opposition to such activity with works like a huge plywood naval ship with a slogan reading "U.S.S. Misery: Resist the War in Central America." Other sculptures in the project included a farmer carrying a gun on her back, a woman with five raised fists, a military helicopter and dozens of crosses, many of them signed by Salvadorans who listed the names of friends and relatives killed in the war.

Before the destruction, artist Suzanne McMillan, referring to military helicopters that fly over the Bay, commented that 'The helicopters we see out here can be carrying weapons." She told the Bay Guardian she would "like to make people aware of that."

But some of the approximately 248,000 freeway travelers who pass by the site each day apparently didn't appreciate the reminder. The morning after the exhibit's opening, the wood helicopter was in splinters, a post the size of a telephone pole had been sawn down and smashed crosses littered the ground. "It was like walking through a bombed village," McMillan said.

Since the Oakland police, the Emeryville police and the state Department of Transportation all maintain the mudflats lie outside their jurisdiction, it is unlikely the vandals will be apprehended. "Artwork like that, it may not be of value, so it the Emeryville Police Department. The artists involved in the project say they do not plan to file charges.

Before the April 5th opening, a number of artists speculated that the Army would level the exhibit. As Minkler said at the opening reception, "The military bases are only miles away, and the military pays large amounts of money to keep relations between the community and the military on a smooth level... My belief is they'll just send some people over to tear it down."

However, the Concord Naval Weapons Station, which had been singled out by one sculpture that consisted of an arrow pointing to "Concord Weapons Station" and another arrow pointing to "Central America," denied knowledge of the incident. "We don't have any feelings pro or con on the display," said Dan Tikalsky, the station's public affairs officer. "If somebody destroyed something that belonged to somebody else, we take a very dim view of that."

Emeryville protest sculpture, 1987.

Photo: Marvin Collins

One sign that the destruction was politically motivated is that the vandals targeted works with messages attached to them, while ignoring those obviously not related to the project, like driftwood dinosaurs built by previous visitors."

The dinosaurs have lived there happily for the last two years," said Braley. "Our stuff came down within eight hours."

The artists have already rebuilt some of the sculptures, and added a sign saying "No Tax Dollars for Central America War" to one of the figures. But they say it's unlikely they'll rebuild the area as extensively as they did before the April 5th opening. "This sort of thing is a transient form," said Braley. "We know that. It's much easier to destroy than it is to put up, so you put it up and get what use out of it you can for the period it's up."

But Braley added that the vandalism showed how vehemently some Americans still oppose efforts to bring the U.S. role in Central America under public scrutiny. "There's not really either freedom of speech or freedom of public art when it comes to statements that are seen as being against the government," he said.