Berkeley’s Establishment of a Police Review Commission

Historical Essay

By Jennifer Andi

| This article investigates the events leading up to the creation of the Berkeley Police Review Commission in 1973. Violence and conflict between the Berkeley police force and civilians in the 1960’s led activists and radicals to shift their efforts to more institutional political methods, such as the ballot measure forwarded in 1971 that called for community control of the police . After the defeat of the ’71 measure, a more moderate approach led to some success in 1973, with the creation of the first official community commission to oversee policing in Berkeley. |

1960’s: Activists Getting Fed up with Police Brutality

The 1960s in Berkeley was marked by a string of protest demonstrations emerging from the University, beginning with the Free Speech Movement in 1964, followed by anti-Vietnam War Protests and finishing the decade with the tumultuous public struggles for ‘People’s Park’ in 1969.[1] Violent suppression of such protests by the Berkeley police fostered a deep mistrust of the police among local activists and community members.

Simultaneous to these campus centered struggles, African-Americans in South Berkeley, Oakland and nearby Richmond responded to violent police oppression through a variety of means including the formation of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. Bobby Seale was the founding chairman of the Black Panther Party (BPP), created in 1966 to provide oversight and protection for Black people in the face of police violence. He wrote, “During those hard core late 1960s racist, fascist times, we took a big chance with our lives patrolling the police. It was a time of rampant vicious police brutality and murder of Black people by police that was 10 times worse than today. We had declared that the racist police occupy our community like foreign troops occupy territory.” Police and government strove to squash the BPP, eventually making new laws to prevent them from patrolling the police.[2]

1970-71, A New Strategy Emerges: Electoral Attempt for Community Control of Police

Seeing the government change laws to eradicate the BPP’s self-defense strategy led Seale to begin organizing for a ballot measure that would give the community control of the police.[3] The BPP found common ground with white activists who had their own struggles with the Berkeley Police Department, and a joint effort to gain community control of the police forces emerged.

The Committee to Combat Fascism, a group affiliated with the Black Panthers, wrote the 1971 Community Control of Police Initiative in Berkeley, calling for the division of Berkeley’s police force into three distinct sections, corresponding to already existing geographical and social distinctions [(1) predominantly Black West Berkeley, (2) predominantly White Berkeley Hills, and (3) university and downtown business district), as well as community oversight of the police. The proposal required that officers live within the department neighborhood of their employment, and called for the creation of three fifteen-member councils and a five-member commission to govern the three departments. Those who supported the measure believed that residence requirements for officers, and local control by citizen commissions would alleviate tensions in the city and foster sensitivity between the officers and community.[4] The BPP’s control of police campaign launched similar initiatives in four different cities in the Bay Area: San Francisco, Oakland, Richmond and Berkeley.[5] Shortly after the referendum was written, Seale was arrested, and the baton was passed to community organizers to collect the needed signatures to get it on the ballot.[6] The strong coalition across racial and ethnic groups in Berkeley worked together to successfully acquire the necessary number of signatures, while the other three cities were unable to gain enough support.[7]

According to long time Berkeley resident and civil rights attorney Jim Chanin, at this time social movements started to see the limitations of protest demonstrations: “It seemed like doing the same thing over and over again, and police response was so violent in response to some demonstrations it led activists, including the BPP, to seek political influence and turn to elections as a vehicle for social change.”[8] Articles in local left newspapers such as the Berkeley Tribe made this transition evident: “It looks like the pigs are going to feel the wrath of the community again. This time, the approach is a little more subtle than usual. Over 15,000 registered voters in Berkeley have signed the Community Control of Police petition.” [9]

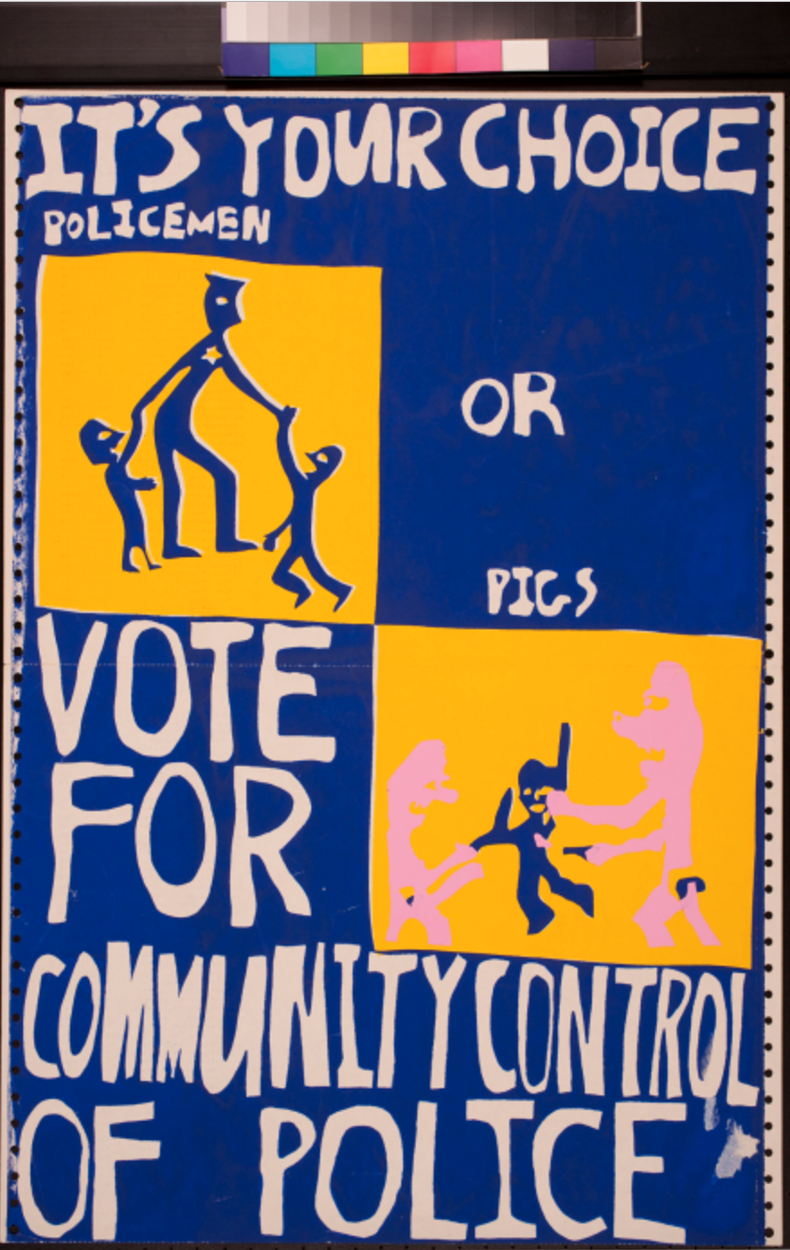

It's your choice - policemen or pigs? Vote for community control of police.

Image: The Media Project

1970 opened a succession of initiative campaigns spanning the decade. Protesters became citizen lawmakers. The 1971 “Community Control of Police” Initiative was one of the first, although ultimately unsuccessful, attempts of Berkeley activists to write changes to the laws and policies that shaped their city. [11]

Political Warfare: The 1971 Community Control of Police Initiative

The police initiative was controversial. While it gained strong support from politically radical African American and New Left student populations, it garnered sharp criticism from conservatives, business owners, and law enforcement agents.[12] New Left radicals in Berkeley frequently clashed with a repressive police force that was concerned with suppressing the political movement to transform the status quo and institute a more democratic government. A 1970 Berkeley Tribe article exhibits well the revolutionary aspirations of those in favor of the initiative- to them, the initiative represented a strategy of using politically legitimate means, to secure space for more radical community activism, and countercultural lifestyles:

Our free way of life has been under systematic attack all this year. The police no longer simply hassle us on the Avenue or attack our demonstrations. They have begun full-scale counter-insurgency to destroy radicalism in Berkeley. They deliberately raid the Free Clinic, Free Church and Runaway Center, attempting to destroy the “permissive liberals” who support our revolutionary community…In pursuing this crackdown, the police have had to expose their brutal nature more and more to the community…In the issue of Community Control of Police we have the chance for a people’s counter-offensive against the occupying army. We are raising a revolutionary question in a “legitimate” arena which large numbers of Berkeley citizens relate to, the arena of electoral politics. We are suggesting an alternative which is both visionary and practical…Above all, we have a chance to unite our whole community; liberals, freeks and revolutionaries, blacks and whites, young and old, around a common understanding of the police and the need for community control in all matters. This unity has been missing at least since People’s Park among whites… In order to achieve unity, we have to present a clear alternative to the police propaganda printed every day in the GAZETTE and also answer the sincere questions many people have about our proposed police control machinery.[13]

We are not asking for a small act like the casting of a “yes” vote’ we are asking people to take charge of their own destinies directly. This is the most contagious meaning of community control. For, after all, the passage of this referendum will only erect a small barrier against the oppressor.[14]

A debate raged in Berkeley between those in favor of the initiative, and those critical of the measure, who worried about the supposedly “divisive” and dangerous results that would follow from such reform. Echoing the debate surrounding Affirmative Action initiatives, A bipartisan group called One Berkeley Community opposed the initiative on the grounds that it was “racially divisive, a step backward by a city that pioneered in total integration of its schools.” Other opposition groups said that the plan would leave Berkeley with an “inferior police force controlled by radicals,” and that if it passed, the 214-member police force would quit because 85 percent lived outside of the district.[15] Radicals were unfazed by the prospect of losing a majority of the current police force, claiming “This would only further expose the police for what they are; an independent armed force who wants Police Control of the Community.”[16]

Another Berkeley Tribe article from 1970 attacks both police propaganda and passive liberals:

The second point of police propaganda is that Berkeley would be racially segregated under this plan. But it is the present system which causes the City to be segregated by communities. The result is that the black community is patrolled by a mainly white police force (there are only 18 blacks out of 272 Berkeley police in a city which is one-third black). Increasingly blacks are refusing to join a police force controlled by their oppressors, and the only alternative to shoot- outs is a police force in the black community chosen by the people. The police control idea starts from the reality of segregation instead of the false “integration” concept which hides the fact of racist domination.[17]

Chronicle – style liberals want to preserve the police to guard the establishment to which they belong. At best they put forward the notion of a police review board or ombudsman to correct “abuses” in police behavior. These proposals will gain respectability in the coming year as “moderate alternatives” to the “radical” idea of Community Control. We will have to argue with many people that a “review mechanism” is impossible when operated under the same system which establishes the police. It can only result in officials reviewing themselves and police policing themselves.[18]

Shortly before the election, Reverend Richard York, a Pastor of the Berkeley Free Church drafted a press release on April 2, 1971, issuing a scathing criticism of the Berkeley Police. He stated that the Berkeley Police Department had forced an illegal entry and conducted an illegal search of the church in February of 1970, and that three officers beat Rev. York unprovoked in July of 1970. He also criticized attempts by the Berkeley City government and police force to discredit the Free Church and the united cause with the April Coalition, going on to discuss the arrest of Father Boylan and accusations of voter fraud. Rev. York renewed his commitment to “eliminate this kind of rank political intimidation and police state behavior by passing the Community Control of Police amendment on April 6, [1971].”[19]

1971: Community Control of Police Initiative is Defeated

The Community Control of Police Initiative failed on April 6, 1971, garnering only 16,144 votes in favor against 33,726 votes opposed.[20] In the wake of the defeat, former City Councilman and newly elected Mayor Warren Widener announced his own plan for “a progressive police department for the entire city.”[21] Warren’s plan retained some of the failed community control specifics, such as a residency requirement, and elected board of police commissioners, but kept the city united instead of dividing it into three precincts.[22] Loni Hancock, who was the only woman elected to the Berkeley City Council in the ’71 election,[23] commented on the failed initiative, “many people liked the idea of community control but had problems with that particular proposal.”[24]

Reflecting on the 1971 police initiative 45 years later, Jim Chanin believes it failed in large part due to divisiveness. It called for physically dividing jurisdictions of the Berkeley Police Department around class and racial lines, and it caused an uproar of political division among supporters and opponents. The initiative was hostilely received, and the Black community voted against it overwhelmingly. Chanin hesitated to say he knew for certain, but got the impression that Black citizens feared that they would be harassed in neighboring jurisdictions and would become officially relegated to their own neighborhoods.[25]

1972-73: A New Attempt at Police Accountability and Oversight

In 1972, organizers regrouped and formed the Police Initiatives Committee. Jim Chanin was one of two campaign coordinators and they applied lessons learned from the failed 1971 Police Initiative in an effort to draft something with at least some oversight principles that could pass. “The idea was cutting edge, but it wasn’t radical,” Chanin said.[26]

The committee focused on inclusiveness over radicalism and built a coalition of support among Black Panther Party, McGovern, Liberal Democrats, Leftists, Progressives, African Americans, and others. The major compromise in the pursuit of the ’73 initiatives compared to the original ’71 initiative, was keeping Berkeley intact as one jurisdiction.[27]

Another strategy shift was to put multiple smaller initiatives on the ballot, rather than trying to push one comprehensive initiative with multiple parts. The initiative for weapons regulations to demilitarize Berkeley PD lost by a small margin. The initiative for a residency requirement mandating that all Berkeley police officers live within the city failed, and residency requirements have since been deemed unconstitutional. The Initiative for the Mutual Aid Ordinance passed, requiring every single mutual aid pact that is made between Berkeley and other law enforcement agencies to be listed and voted in by City Council every year. But the main success from their strategy was the passing of the initiative for a Police Review Commission.[28]

Berkeley Police Review Commission: Obstacles, Successes, and Future

In the immediate aftermath of the successful initiative, there were obstacles to the implementation of the commission. The legality of the initiative was questioned because it was written as an ordinance instead of a charter amendment, and a typewriter error omitted a line of text from the ordinance. The PRC had to sue to uphold the initiative, and to demonstrate the intent for each City Council member to appoint one commissioner, as was specified in the line of text that was omitted. Jim Chanin was a commissioner on the first Police Review Commission (PRC) and ultimately served as a commissioner from 1973-77, and 1979-80. The City Manager at the time was supportive of the PRC in offering to reinstate portions of the ordinance, as well as providing a budget and an office for the PRC .[29]

Many feel PRC in its early years was successful in holding the police accountable, and in implementing policies such as hostage negotiation instead of SWAT team extraction. Over time, and with the change of people in power, the City government began to limit PRC’s rights and power.[30]

Beginning in the 1990s, public critique of the PRC’s ability to deliver on its mission of ensuring police accountability has grown. Matthew Arnatz’s 2002 article on the 30th anniversary of the PRC exhibits one such critical perspective on the matter:

Today’s Berkeley Police Department bears little resemblance to the force that fired on People’s Park protesters in 1969 and prompted voters to approve one of the nation’s first citizen review commissions four years later. …But for the Police Review Commission—which spearheaded those reforms and celebrated its 30th anniversary Thursday—little has changed. It’s still fighting for relevance and still steeped in controversy. “It’s a biased venue that does a disservice to the community,” said Randolph Files, president of the Berkeley Police Association— which has considered the PRC to be a knee-jerk anti-cop panel since its inception. Increasingly, though, the sharpest criticisms have come from advocates for the accused, who argue that the commission has lost its activist zeal and retreated from the community whose support it needs to remain relevant. “[The PRC] isn’t loved by the bureaucracy, so if it’s not loved by the people, I don’t see them having a 40th anniversary,” said Andrea Pritchett of Copwatch, an independent organization that monitors alleged police misconduct. … “It’s only as strong as the commitment and energy of the commissioners,” said Osha Neuman, who served from 1984-1992. … Still, when it comes to actual complaints against officers, the PRC’s findings carry little weight. No one interviewed could recall a case when an officer was fired or disciplined as the result of a commission finding. … A 2002 California Court of Appeals ruling further eroded the commission’s disciplinary power by mandating that cities with citizen review commissions set up appeal bodies for officers seeking to strike sustained allegations from their record. According to commissioners, since the process started last year, the three-person appeal board selected by then-City Manager Weldon Rucker has overturned nearly every commission finding against officers. “I’m astounded by their decisions. It’s ridiculous,” said Commissioner David Ritchie. … “If I had a serious complaint, I wouldn’t go to the PRC,” Prichett said. “Often you’re left to deal with the bureaucracy and present your case by your lonesome, and if you lose, it hurts your court case.” She said that, unlike previous boards, current commissioners aren’t hitting the streets to promote their activities or monitor police conduct. Commissioners past and present disagree, saying the PRC has provided an invaluable outlet for police-community dialog that has improved policing in the city and help Berkeley steer clear of the expensive misconduct suits that have plagued Oakland and San Francisco.[31]

Anderson Lanham’s 2016 article in the Daily Cal discusses some of the issues the PRC faces today :

“The Police Review Commission in Berkeley was designed to oversee the Berkeley Police Department, to hold its officers accountable for their actions and to act as a liaison between the department and the community. But at a time when police violence and oversight has become the subject of ever-increasing controversy across the nation, many in Berkeley — and in the commission itself — feel that the PRC is unable to adequately address today’s foremost police issues. “I demand accountability from the police department,” said Police Review Commissioner Ayelet Waldman during a PRC meeting, adding that such accountability is unachievable given the powerlessness of the commission. “To participate in a system that appeases rather than being effective, that gives the illusion of justice when no justice is being attained, then that is worse than not participating.” According to Berkeley City Councilmember Kriss Worthington, one consequence of this lack of justice is the fact that some civil rights lawyers in Berkeley explicitly tell their clients not to take their complaints against the police to the PRC. Civil rights lawyer James Chanin, who is also a founding member of the PRC, said the commission’s actions are evidence of its ineffectiveness… The PRC is currently facing issues operating within state law and city law, which are both restrictive regarding disclosing police records. PRC Commissioner George Lippman credits this lack of access to the enormous lobbying power of the police association… “I want a robust and important (Board of Inquiry),” Waldman said. “If we can achieve that within this system or within this time frame — making sure that the chief considers the (board’s) reports in his decision — then (I support conducting such inquiries). But if we can’t do that, I think that continuing this process is a disservice to the community.”[32]

At the time of this article (2017) Berkeley PRC is still operating in Berkeley, and other independent organizations such as Copwatch are contributing to the effort of holding police accountable.[33] On the national front, Black Lives Matter has taken issues of police brutality and accountability back to the streets in the form of widespread protests and calls for reform.The heightened tensions between police and communities of color have brought discussions about the role of community review back on the table. The opportunity appears ripe for the formation of new coalitions to push forward radical change in policing.

Notes

[1] David D. Schmidt, "Two Case Studies." Citizen Lawmakers: The Ballot Initiative Revolution, (Philadelphia, Temple

UP, 1989).

[2] Bobby Seale,"berkeley-ballot-in-1969/ Bobby Seale: Community Control of Police Was on the Berkeley Ballot in 1969," San Francisco Bay View, 13 Aug. 2015, (accessed 6 Dec. 2016).

[3] Seale," Bobby Seale: Community Control of Police Was on the Berkeley Ballot in 1969."

[4] Tim Reiterman, "Berkeley To Vote On Splitting Police Department; Radical Groups Support Plan," Cielodrive.com, 5 Mar.1971, (accessed 08 Dec. 2016).

[5]Panthpol

[6] Seale," Bobby Seale: Community Control of Police Was on the Berkeley Ballot in 1969."

[7] Seale," Bobby Seale: Community Control of Police Was on the Berkeley Ballot in 1969."

[8] Interview with Jim Chanin by Jennifer Andi, November 11, 2016.

[9] Berkeley National Committee to Combat Fascism, "Community Control," Berkeley Tribe, 21 July 1970, 2.

[10] The Media Project, “It’s your choice – policemen or pigs? Vote for community control of police,” (1971), AOUON Archive,(Accessed 26, Sep. 2016)

[11] Schmidt, "Two Case Studies." Citizen Lawmakers: The Ballot Initiative Revolution.

[12] Reiterman, "Berkeley To Vote On Splitting Police Department; Radical Groups Support Plan."

[13] Tom Hayden, "N.C.C.F.,” Berkeley Tribe, 2 Oct. 1970, 12-13.

[14] Hayden, "N.C.C.F.”

[15] Reiterman, "Berkeley To Vote On Splitting Police Department; Radical Groups Support Plan."

[16] Hayden, "N.C.C.F.”

[17] Hayden, "N.C.C.F.”

[18] Hayden, "N.C.C.F.”

[19] Rev. Richard York, Statement of the Rev. Richard York, Pastor of the Berkeley Free Church. (2 Apr. 1971), Online

Archive of California, (accessed 8 Dec. 2016).

[20] David Mundstock, “Chapter 2 – The 1971 Election and the April Coalition,” Berkeley Citizens Action, (Accessed 5 Oct. 2016).

[21] Mundstock, “Chapter 2 – The 1971 Election and the April Coalition.”

[22] Charlie Davis, "Countin' on Warren Widener," Berkeley Barb, 9 Apr. 1971, 2&8

[23] Mundstock, “Chapter 2 – The 1971 Election and the April Coalition.”

[24] Davis, "Countin' on Warren Widener.”

[25] Interview with Jim Chanin by Jennifer Andi, November 11, 2016.

[26] Interview with Jim Chanin by Jennifer Andi, November 11, 2016.

[27] Interview with Jim Chanin by Jennifer Andi, November 11, 2016.

[28] Interview with Jim Chanin by Jennifer Andi, November 11, 2016.

[29] Interview with Jim Chanin by Jennifer Andi, November 11, 2016.

[30] Interview with Jim Chanin by Jennifer Andi, November 11, 2016

[31] Matthew Artz, "Police Commission Marks 30 Years of Controversy," Berkeley Daily Planet, 2 Dec. 2002, (accessed 11 Nov. 2016).

[32] Anderson Lanham "Policing the Police," The Daily Californian, 24 July 2016, (Accessed 10 Nov. 2016). [33] (Insert hyperlink to possible Copwatch article)