Berkeley Tenants Union in the 1970s

Historical Essay

by Justin Germain

| Established in late 1969, the Berkeley Tenants Union, the first of its kind in the area, aimed to organize low-income tenants to protest evictions, rent increases, and poor housing conditions throughout Berkeley. At the same time, the tenants union formed strong coalitions with other activist groups in the hopes of attaining community control over living space. While unsuccessful in fulfilling their revolutionary desires, the Berkeley Tenants Union drastically increased tenants’ political power and put housing reform at the forefront of local public discussion. |

Tenants Rising V.1:7, the official biweekly newspaper of the Berkeley Tenants Union

Image: Bancroft Library

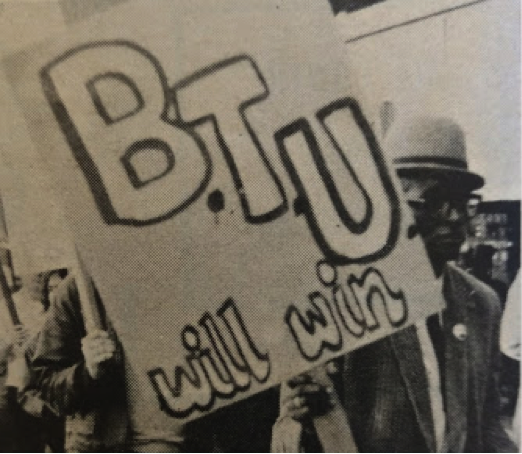

November 13, 1969 protest at the National Association of Real Estate Board’s annual convention.

Image: Tenants Rising V.1:7, Bancroft Library

Scribbled on a 1969 questionnaire distributed by the Berkeley Tenants Union, an East Berkeley mother wrote that she was a “divorcee, [had] two small children, part time job, and must sublet the two rooms to live in the house…my conscience hurts - the landlord’s does not.”[1] Amidst the rapid social changes of the late 1960s, San Francisco Bay Area residents began to speak out against the economic exploitation of low-income communities through rising rents and police-enforced evictions. Yet this was no easy task; individuals and their families found it nearly impossible to sway wealthy, seemingly unconscionable landlords who were intent on optimizing profits. Berkeley residents were the first in the Bay Area to organize for tenants’ economic rights through the creation of the Berkeley Tenants Union (BTU) in 1969. The BTU aimed to “become the collective bargaining agent for tenants and to be recognized by landlords as such” in an age with little organizing around housing or neighborhood issues.[2] The organization’s goals went beyond negotiations however, as they aspired more broadly to use the tenants’ union to give people absolute control over the space in which they lived. These revolutionary ideals guided the BTU throughout its first ten years of existence and influenced Berkeley residents’ views towards housing for decades. It did not, however, emerge out of a vacuum; tenant-landlord tension had been skyrocketing across the country for years.

Context

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, the United States was in the middle of a colossal urban housing crisis. At the time, twenty-six percent of all American housing was considered downtrodden or lacking in appropriate sanitary facilities. Even with these abhorrent conditions, property values increased twelve percent annually (to landlords’ joy), with the value of high density Berkeley housing inflating at an even faster pace. Yet 70 million Americans (including the majority of people living in cities) were tenants, which typically meant that they were stuck in deteriorating housing that cost more and more to live in with each passing month.[3] Although tenants had protested unfair payments and conditions by collectively withholding their rents in previous decades, the frequency of rent strikes ballooned in the mid-1960s. Myron Moskovitz, one of the former attorneys for the Berkeley rent control movement in the mid-1970s, attributed this dramatic increase to the popularity of community organizing in the consumer, environmental, and anti-war movements. One of the most common ways to channel this spirit of mobilization against exploitative landlords were tenant unions: community groups that used collective bargaining tactics to ensure tenants’ rights were respected. The first tenant unions emerged in Chicago in 1966 and spread to 29 different cities by 1969.[4]

The East Bay became a bulwark of tenants’ rights activism. While San Francisco would not experience mass tenant organizing until the late 1970s, Berkeley residents organized on one of the nation’s largest scales a decade earlier. Some structural factors point to this. The city classified two-thirds of all Berkeley households (two-thirds of which were rentals) as “low to moderate” income.[5] Furthermore, according to a 1973 housing survey, over 6,000 Berkeley units required “substantial repairs, major rehabilitation or replacement.”[6] One group of renters got so fed up with the downtrodden state of their rental that they left a dead cow in their common hallway to protest the lack of proper fire exits. Landlords exploited conditions like these to earn more revenue, even though rental payments in Berkeley only garnered approximately 8% profit on average.[7] In such a state, the Berkeley City Council initiated reforms to make housing more affordable, especially for low-income tenants. Housing was even named as the Berkeley Planning Commission’s highest priority in 1972. One of the Council’s most innovative reforms was the 1973 Neighborhood Preservation Ordinance, which allocated a proportion of new housing for low and moderate-income families.[8] Yet the resolution’s most notable feature was its goal to “revise the Master Plan with neighborhood participation in development decisions.”[9] This was a direct response to the mass, tenant-based organizing that had captured the city’s attention during the preceding four years. The community’s desire to gain political control over housing development emerged from the dedicated campaigning of the Berkeley Tenants Union.

Formation of the BTU

“Landlords are thieves,” exclaimed a writer for Tenants Rising, the Berkeley Tenants Union’s biweekly newsletter, “but their robbery is legal.”[10] Virulent hostility toward landlords was only one driving factor behind the BTU’s formation. Berkeley residents created the union at an August 30, 1969 Gathering of the Tribes “to halt the systematic rent increases which have plagued this community over the past years.”[11] Who originally founded the BTU is a question that has historically been up for debate. According to Berkeley Rent Board Commissioner Katherine Harr, “I’ve met at least 20 people who have claimed to have founded it.”[12] Yet what all the original members of the BTU shared was the drive not to just be a collective bargaining group for tenants, but to be the only one in Berkeley. Although the BTU would become the largest and most effective tenants union in the city, it did not achieve this lofty goal. The BTU primarily focused its efforts in East Berkeley and near the University of California campus, while TORCH, a similar yet smaller tenants union, organized in West and South Berkeley (primarily for black and Chicano communities).[13] Garnering community support for BTU and TORCH was not a very difficult task. The organizing spirit left over from the Free Speech Movement and local antiwar activism had formed a coalition of students, minorities, and progressives eager to get involved. More importantly, the People’s Park Protests in April and May 1969 sparked a newfound interest in housing issues and challenged existing concepts of property rights. Only a few months later did the BTU begin reaching out to the public for support and involvement.[14] What made the BTU distinct was its hardline demeanor towards their strike pledge. “To be a member of BTU, you have to sign a piece of paper,” explained Harr, now the secretary of the Berkeley Tenants Union, “that says you pledge to uphold our mission.”[15] In late 1969, that mission included agreeing to withhold rent once 2000 other members agreed to begin a rent strike. Although some members believed that a strike pledge was worthless, the BTU insisted that these contracts helped to legitimize their collective action in the eyes of profit-hungry landlords.[16] Planning a city-wide rent strike would soon become the focal point of BTU’s organizing throughout late 1969 and early 1970.

Strategy and the Rent Strike

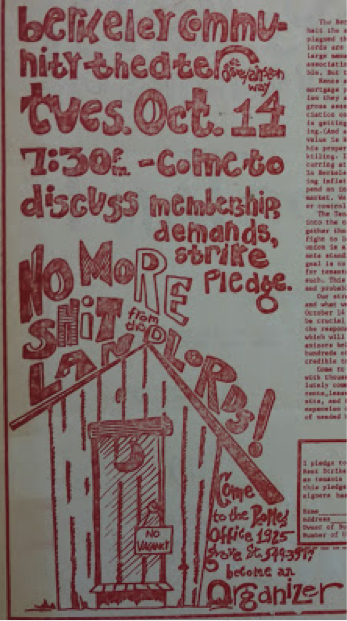

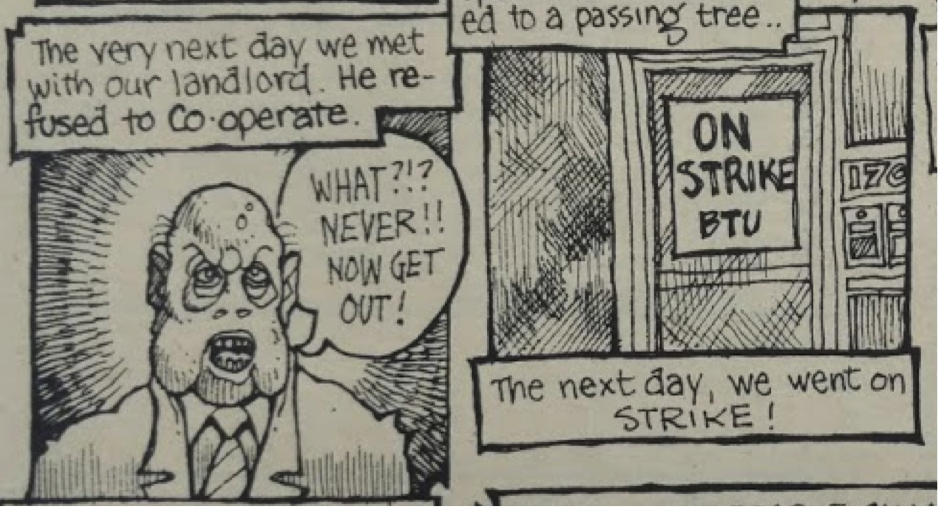

On September 11, 1969, the Berkeley Tenants Union held a public meeting for concerned citizens to help structure the organization during its first full month of operation. Tenants and organizers decided that they would “intensively organize on a block-by-block basis for a month,…supply tenants in their neighborhoods with information…[and] encourage them to get together to discuss the issues of a strike, escrow funds, membership requirements, tactics, etc.”[17] They scheduled their next “mass meeting” for October 14th to decide whether to change their mobilization strategy. In the meantime, they held weekly meetings (often recording head counts of up to 100 people) to arrange smaller, day-to-day tasks.[18] By the October meeting, the BTU had received more support than they could have ever imagined. 125 organizers in six different municipal regions hit the streets to canvass residents while almost 1,000 tenants attended the October restructuring meeting to voice their opinion about “membership criteria, minimal demands, and the structure of the Berkeley Tenants Union.”[19] In order to make the BTU as accessible as possible, meeting attendees decided that any tenant could join the union, but could only vote on important decisions if they agreed to sign the strike pledge. Also designed for accessibility, Tenants Rising’s bold, obscene headlines and full-page comics (portraying landlords as grotesque monsters) helped to expand their membership in creative ways.[20] With such immediate support, the possibility of a large-scale rent strike became increasingly likely. Other Berkeley residents felt similarly. In late September, University of California students picketed local apartments in support of a small rent strike against the Values, Inc. property management company due to their decision to increase rents by 33%.[21] As the new decade creeped closer, more and more tenants seemed willing to organize on a mass scale to defend their economic rights.

Flyer for the Berkeley Tenants Union’s mass meeting on October 14, 1969

Image: Tenants Rising, V.1:3, Bancroft Library

“Tenants Toons” portrayed landlords as hideous monsters in Tenants Rising

Image: Tenants Rising, V.1:8, Bancroft Library

Accordingly, BTU’s main focus during the first quarter of 1970 was organizing a citywide rent strike. By that year, Berkeley’s vacancy rate was at a paltry 3.6%, and more than half of the city’s rentals had been occupied for under a year. While the city formed a Rental Housing Committee to investigate tenant-landlord disputes, the BTU decided to pursue much more radical measures. On January 3, 1970, the front page headline of Tenants Rising made a bold announcement: “RENT STRIKE PROJECTED FEBRUARY 1.”[22] At the time, the BTU only had 600 members who had signed the strike pledge. The voting committee had chosen to abandon the requisite 2000 pledges needed to launch a mass strike in favor of a system based on tenant-to-landlord ratios. With this in mind, the BTU decided to go forward with the rent strike, yet it ended up happening on a much smaller scale than initially planned. Around five hundred units withheld their rents until mid-March to varying degrees of success. Some units received better rental agreements while one unit was actually able to buy the property from their landlord.[23] It did not revolutionize property ownership throughout Berkeley, but it definitely provided more agency to at least some struggling tenants.

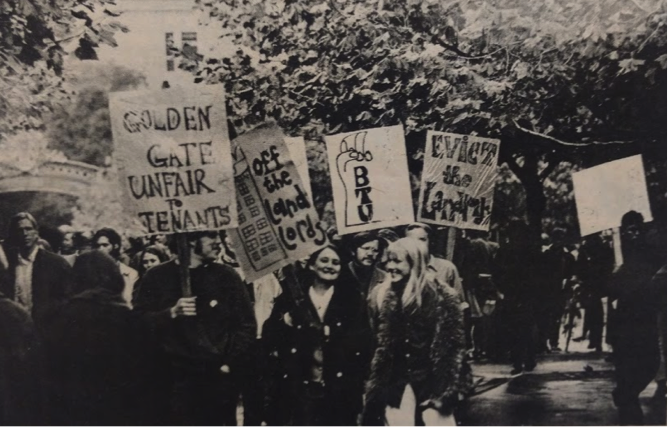

While the rent strike was the BTU’s “top priority aim….since the beginning,” the tenants union had notable success in preventing unfair evictions and rent increases. The BTU’s initial targets were “large realty and management companies” because they gained the most through rampant speculation and widespread tenant exploitation.[24] One of the first firms that the BTU campaigned against was the Kobos Investment Company in November 1969. The landlord group had evicted tenants for the sole purpose of putting new dishwashers in all of their apartments (and raise the rent by $60 - $75 in the process). The BTU organized approximately three-quarters of Kobos’ tenants on their Wheeler Street property and demanded a repeal of the evictions, a 50% decrease in rents, and recognition of the BTU as the building’s collective bargaining organization. On November 5, 1969, BTU and the Kobos tenants marched to the main office of the Golden Gate Management Company (which oversaw Kobos and 500 Berkeley units in total) with their demands in hand.[25] Two days later, Kobos withdrew the evictions and began negotiating with the BTU about collective bargaining recognition. A smattering of other successes included lowering rents for a complex on Dwight Avenue by $30-$40 per month, blocking an eviction threat by San Francisco Federal Savings for tenants living on Colby Street, and mobilizing over 125 units under Golden Gate Management’s oversight.[26] Community organizing, however, was just one branch of BTU advocacy, they also dedicated substantial time and effort toward implementing a citywide policy of rent control in the early 1970s.

November 1969 BTU protest against Golden Gate Management Company at the University of California, Berkeley

Image: Tenants Rising, V.1:6, Bancroft Library

The Fight for Rent Control

The Berkeley Tenants Union’s involvement in the fight for rent control lasted well into the 1980s. Due to years of coalition-style organizing by the BTU, the University of California’s Tenant Action Project, and the April Coalition (a progressive local political slate), Berkeley residents passed a strong rent control initiative in June 1972. According to regional planner Pierre Clavel, “it established base rents, rolled back to their August 1971 levels,….applied to all private rentals for housing….[and] regulated evictions.”[27] The legislative success even spurred rent control supporters to run housing reform candidates for City Council in the January 1973 election. Unfortunately, this victory was short-lived. Rent control opponents filed a lawsuit against the initiative, which made its way to the California Supreme Court in 1976. In Birkenfeld v. the City of Berkeley (1976) 17 Cal.3d 129, the court ruled that Berkeley’s rent control law was unconstitutional because its “cumbersome rent adjustment procedures….would deprive the plaintiff landlords of due process of law.”[28] The case did not bar cities from implementing rent control as long as it followed specific procedures; a victory in the face of defeat for many, including the BTU. According to Berkeley historian David Mundstock, in this new phase of organizing, the BTU “claimed that as the only Berkeley organization exclusively run by and for tenants, it had the right to exercise veto power over all rent control drafting decisions.”[29] After organizing a second rent strike that lasted eighteen months from 1974 – 1975, BTU relocated its effort to Measure B, a new and notably strict rent control ordinance. Unfortunately for the union, the City Council defeated the proposal 3-5 on March 15, 1977.[30] When Berkeley interest groups created a more moderate rent control proposal in March 1980, the BTU opposed it, claiming that it was not strong enough to protect tenants. It would take until 1984 with the California Supreme Court’s approval in Fisher v. City of Berkeley (1984) 37 Cal.3d 644 for the first official (yet relatively moderate) rent control legislation to become law in Berkeley.[31]

Trainings and Coalition Building

Amidst all of the eviction, rent control, and rent increase fights, the Berkeley Tenants Union established a distinct set of programs designed to help low-income tenants gain the capabilities to organize on their own. As a short-term solution, BTU members offered free living space to evictees during the period the union was contesting their eviction. Within a few weeks of its formation, BTU began offering training “in basic tenant-landlord law for all organizers” with help from the Movement Liberation Front.[32] They also set aside $2500 to form a legal staff that would help union members in court and offer tenants any requested legal advice. Similarly, the February 30, 1970 issue of Bar Sinister News, a tenants’ rights newsletter jointly issued by BTU and TORCH, outlined one important aspect of the unions’ legal procedures on the front page of every issue.[33] Furthermore, the BTU even offered a Relief Squad that tenants could contact if their landlords had committed violence against them. Outside of the housing realm, the BTU often coordinated events with local food conspiracies to help control rising food costs (a disproportionately large burden for tenants on the ropes with their landlords).[34] As the tenants union grew, it began to spearhead more coalitions, which was a testament to their goal of becoming more than just a tenants’ rights advocacy group.

The Berkeley Tenants Union actively worked to promote cross-movement solidarity throughout the Bay Area. Most notable was its joint publication of later issues of Tenants Rising with the Black Panther Party. With this relationship in mind, the BTU campaigned against police brutality throughout the Berkeley community, especially since many of their organizers still held anti-police sentiment after the People’s Park protests.[35] During eviction mobilizations, the union would often lambast the “inflammatory presence of Alameda County sheriffs” and the “pigs….led by Mayor Johnson.”[36] Tenants Rising even published a letter from University of California, Santa Barbara students in their call for protest support against an officer who drove his cruiser over a student. Solidarity with the antiwar movement was also notably strong. The BTU helped to organize a student strike vote at the Barrington Cooperative in May 1970 to try and build “a united movement” against the Vietnam War.[37] On the domestic front, the BTU aligned with Women’s Liberation to prevent gender discrimination in housing and put pressure on the state for new child care centers throughout the city.[38] Solidarity was a key BTU principle, as they coordinated citywide efforts with People’s Architecture, the Berkeley Tribe, Ecology Action, the West Berkeley Poor People’s Council, and the North Berkeley Neighborhood Council for a wide variety of progressive causes.[39] With this sense of cooperation in mind, the union wanted to create “the most serious and joyous community organizing movement Berkeley has ever seen!”[40] In following such aspirations, the BTU set themselves the lofty goal of affecting a property control revolution.

Revolutionary Dreams, and Significant Success

The Berkeley Tenants Union aimed to use tenant mobilization to gain community control of housing. “Building a strong tenants union” was the first and most vital step to establishing “popular control of living space,” which included maintaining a resident-dictated cost of living and “asserting through collective action the community’s needs for a healthy environment.”[41] One powerful method to achieve this end was to increase the political legitimacy of the neighborhood. Community organizing had been key to getting City Council to pass the 1973 Neighborhood Ordinance and other policies specifically focused on the neighborhood as a political unit. On a long-term scale, granting individual neighborhoods more power and improving housing programs were both part of a larger goal of controlling city wealth.[42] The Berkeley Tenants Union did not just want to provide short-term fixes to tenants’ problems, they wanted to overhaul the hierarchical, capitalistic housing system that created these problems in the first place. They believed that forming a tenants union was “profoundly subversive” and allowed them to accomplish “experiments in community control,” such as preserving aged homes and limiting the growth of BART and the University of California.”[43] In and of itself, the Berkeley Tenants Union was an experiment, and a fairly successful one at that. While it did not revolutionize the relationship between tenants and landlords, it provided services that the city of Berkeley was unwilling or unable to, while drastically increasing low-income renters’ political power. The BTU centered the city’s political focus on affordable housing, an issue that would plague Berkeley for decades to come. As shown by BTU’s victorious protests against large property firms, landlords intent on profit-mongering would now have to consider whether evictions or rent increases were worth community outrage. Through these actions, the BTU created a new community of activists that took the reins of local housing debates and gave them firmly to the people.

As this hammer and anvil indicate, the BTU aimed to revolutionize property and wealth control in Berkeley.

Image: Tenants Rising, V.1:6, Bancroft Library,

Transformations and The BTU Today

As a result of infighting and a lack of community fervor, the BTU went dormant in the early 1980s. It took over thirty years for the organization to re-emerge, with Berkeley Rent Board Commissioner Judy Shelton leading the charge to revive the union. The BTU of the twenty-first century had one key difference. As Commissioner Harr pointed out, the “new” BTU still provided necessary legal and community resources to struggling tenants (especially students), but lacked the radicalism and revolutionary mission that the “old” BTU so fervently advocated for.[44] Even without this larger goal, the BTU of today is dedicated to combatting evictions, providing tenants with legal advice, and advocating for tenants’ rights throughout Berkeley. Through these services, the BTU maintains its legacy of creating an environment where struggling citizens have the means to participate in and influence their community. This foundational principle has guided the tenants union throughout its entire existence, and has driven the BTU to redefine what it truly means to live in a community.

Notes

[1] “Tenants Rising: Berkeley Tenants Union,” Tenants Rising, September 22, 1969, 1, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

[2] “Community Meeting,” Tenants Rising, October 1969, 1, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

[3] Tova Indritz, “The Tenants’ Rights Movement,” New Mexico Law Review 1, no.1 (1971):

4, 1, accessed October 3, 2016; “Community Meeting,” October 1969, 1.

[4] Indritz, “The Tenants’ Rights Movement,” 14, 18; Myron Moskovitz, “The Great Rent Control War,” Publications 159 (2010): 2-3, accessed September 26, 2016.

[5] The People of Berkeley - A Policy, City of Berkeley Planning Commission, August 1974, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 2; Housing Element: Berkeley Master Plan, 6.

[6] Housing Element: Berkeley Master Plan, City of Berkeley Planning Commission Housing Committee, July 31, 1975, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 15.

[7] Indritz, “The Tenants’ Rights Movement,” 29; “Community Meeting,” October 1969, 1.

[8] Housing Element: Berkeley Master Plan, 3; The People of Berkeley – A Policy, 25.

[9] The People of Berkeley – A Policy, 5.

[10] “Community Meeting,” October 1969, 1.

[11] “Strike Meeting,” Tenants Rising, January 3, 1970, 8, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley; “Community Meeting,” October 1969, 1.

[12] Interview with Katherine Harr by author, November 10, 2016.

[13] Two-thirds of Berkeley’s African-American population lived in West and South Berkeley. BTU and TORCH would often work together to hold joint tenants rights’ rallies. Pierre Clavel, The Progressive City: Planning and Participation, 1969-1984 (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1986), 107; “BTU-TORCH Rally,” Tenants Rising, November 1969, 1, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley; The People of Berkeley – A Policy, 8; “The Great Berkeley Rent Strike,” Berkeley Tenants Union, Berkeley Tenants Union 1970 – 1979 Collection, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

[14] Eve Bach et al., The Cities’ Wealth: Programs for Community Economic Control, Institute for Policy Studies Conference on Alternative State and Local Public Policies, 1976, 3; Clavel, The Progressive City, 108; “Tenants Rising: Berkeley Tenants Union,” September 22, 1969, 1.

[15] Interview with Katherine Harr by author, November 10, 2016.

[16] “Sample Strike Pledge,” Tenants Rising, October 1969, 1, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley; “Tenants Rising: Berkeley Tenants Union,” Tenants Rising, October 22, 1969, 2, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

[17] “Tenants Rising: Berkeley Tenants Union,” September 22, 1969, 1.

[18] Ibid.

[19] “Community Meeting,” October 1969, 1.

[20] “Tenants Rising: Berkeley Tenants Union,” Tenants Rising, October 22, 1969, 1, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley; “Tenant Toons,” Tenants Rising, March 11, 1970, 1, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

[21] “Berkeley radicals press demands: Landlords brace for rent boycott,” The BG News, September 25, 1969, 4, accessed October 1, 2016.

[22] Housing Element: Berkeley Master Plan, 10, 26; “Rent Strike Projected February 1,” Tenants Rising, January 3, 1970, 1, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

[23] “Rent Strike Projected February 1,” January 3, 1970, 1; Clavel, The Progressive City, 107.

[24] “BTU Halts Evictions,” Tenants Rising, November 25, 1969, 1, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

[25] Ibid; “BTU-TORCH Rally,” November 1969, 1.

[26] “BTU Halts Evictions,” November 25, 1969, 1; “Golden Gate is Falling Down,” Tenants Rising, January 3, 1970, 7, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

[27] Clavel, The Progressive City, 118.

[28] David Mundstock, “The New City Council, 1971 – 1973,” in Berkeley in the 70s: A History of Progressive Electoral Politics, accessed October 27, 2016; David Mundstock, “Rent Control Returns,” in Berkeley in the 70s: A History of Progressive Electoral Politics, accessed October 27, 2016.

[29] Moskovitz, “The Great Rent Control War,” 6; David Mundstock, “The Buzz Wilms Boomlet,” in Berkeley in the 70s: A History of Progressive Electoral Politics, accessed October 27, 2016.

[30] “Eviction Trial, February 22, 1975,” Berkeley Tenants Union, Berkeley Tenants Union 1970 – 1979 Collection, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley; Mundstock, “The Buzz Wilms Boomlet,” Berkeley in the 70s.

[31] David Mundstock, “The June 1980 Election - Rent Control on the Brink of Extinction or Expansion,” in Berkeley in the 70s: A History of Progressive Electoral Politics, accessed October 27, 2016; Moskovitz, “The Great Rent Control War,” 14.

[32] “Strike Meeting,” January 3, 1970, 8; “Tenants Rising: Berkeley Tenants Union,” September 22, 1969, 1.

[33] “Tenants Rising: Berkeley Tenants Union,” Tenants Rising, October 22, 1969, 3, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley; “Tenants Rising: Berkeley Tenants Union,” September 22, 1969, 1; “Outline of Legal Procedure,” Bar Sinister News 1, no.2, February 30, 1970, Berkeley Tenants Union 1970 – 1979 Collection, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

[34] “The Great Berkeley Rent Strike,” Berkeley Tenants Union, Bancroft Library; “Food Conspiracy,” Tenants Rising, November 25, 1969, 3, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

[35] “Berkeley,” Tenants Rising, March 11, 1970, 2, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley; Clavel, The Progressive City, 104.

[36] “The Great Berkeley Rent Strike,” Berkeley Tenants Union, Bancroft Library; “Berkeley,” March 11, 1970, 2.

[37] Cindy Heaton and Louis Dewie, “To the Berkeley Student Body,” Berkeley Tenants Union 1970 – 1979 Collection, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley; “Noon Rally,” Berkeley Tenants Union, Berkeley Tenants Union 1970 – 1979 Collection, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

[38] “Landlords Down on Women!” Tenants Rising, January 3, 1970, 3, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley; “Child Care Centers Now!” Tenants Rising, November 25, 1969, 3, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

[39] “Control Your Community,” Tenants Rising, November 25, 1969, 1, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley; “Strike Meeting,” January 3, 1970, 8; “Grow Your Own,” Tenants Rising, March 11, 1970, 8, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

[40] “Strike Meeting,” January 3, 1970, 8.

[41] “Control Your Community,” November 25, 1969, 1.

[42] Clavel, The Progressive City, 120; Bach et al., The Cities’ Wealth, 19.

[43] “Saga of the tenant union,” Tenants Rising, November 25, 1969, 2, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

[44] Today the Berkeley Tenants Union is located in the Grassroots House, a space for progressive organizations that also houses Copwatch and the Alameda County Chapter of the Green Party. Interview with Katherine Harr by author, November 10, 2016.