Japanese Internment in San Francisco

Historical Essay

by Erica Loberg

| After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the U.S. government imprisoned over 100,000 people of Japanese ancestry living along the Pacific coast in specially made camps. Preparing for a possible Japanese invasion, the government depicted this as a necessary precaution against the potential disloyalty of members within this population. Ultimately, Japan did not invade the U.S., and this internment greatly disrupted the progress of Japanese culture in the United States by challenging the conceptions of identity held by young Japanese Americans and fracturing the communities in which they previously lived. |

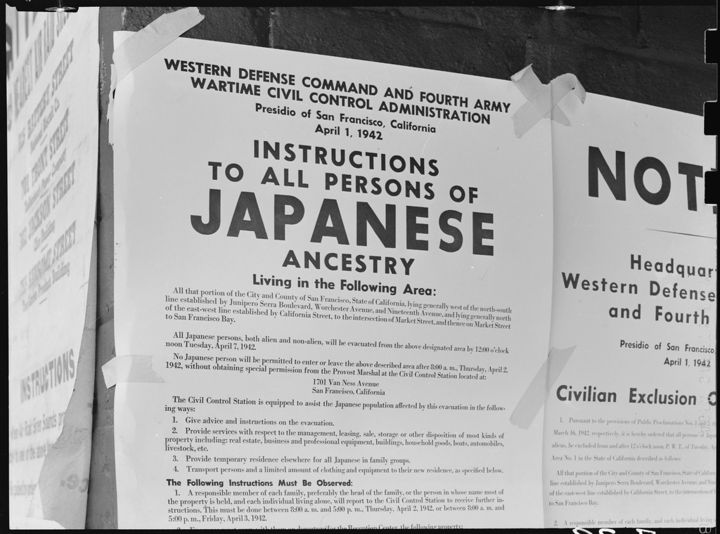

“Posted exclusion orders” by Dorothea Lange, 1942.

Photo: courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

“Japanese American boarding up store” by Dorothea Lange, 1942.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

The Japanese internment began with President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, issued on February 12, 1942, two months after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Authorized by the order, the U.S. Army and War Relocation Authority evacuated all Japanese people, both immigrants and natural-born citizens, from their homes. For the sake of urgency, they were first sent to temporary assembly centers while more permanent barrack-style communities were built in more inland states such as Arizona and Utah. These communities had schools, cafeterias, gathering spaces, and even farm and work areas so that residents’ entire lives were confined to the camps, which were supervised by armed guards.

In 1944, the U.S. War Relocation Authority and U.S. Office of War Information produced informational videos showing the evacuation and living conditions of the Japanese during internment. The former, below, depicts various aspects of life within the camps, as well as the successful jobs of Japanese Americans after release and relocation. The second, shown below, offers more information on the initial evacuation of Japanese from their homes. Both videos pointedly defend the internment by 1) explaining its necessity as a means of ensuring national security, 2) illustrating humane living conditions to contest any claims of unconstitutionality, and 3) assuring non-Japanese Americans that their tax dollars are not being extravagantly used to maintain the apprehended population.

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/Challeng1944" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

A Challenge to Democracy by the U.S. Wartime Relocation Authority

Video: Prelinger Archive

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/Japanese1943" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Japanese Relocation by the U.S. Wartime Relocation Authority

Video: Prelinger Archive

Although the government claimed to believe that most people of Japanese ancestry in the U.S. did not pose any danger to the American war effort, they justified the internment of all Japanese people by their suspicion that a few, whom they had no way of identifying, might betray the U.S. for their home/ancestral country. At the end of one video, the narrator mentions that many Japanese Americans volunteered to fight in the war while they were at relocation centers, fighting for “American ideals…[including] democracy, freedom [and] equality of opportunity, regardless of race, creed, or ancestry” (A Challenge to Democracy 1944). Astonishingly, the government thus denied the contradiction between their words promoting American idealism and their cruel actions in locking over 100,000 innocent people in camps where they were forced to work solely because of their ancestry. The government defended this large-scale, federal racial profiling as a protection of the entire nation, at the expense of a significant number of its own citizens.

The psychological impact of the internment is especially apparent when looking at the experience of the Nisei, first generation Japanese Americans, throughout this ordeal. In a study published by the National Youth Administration Junior Counseling Service in 1941 before the internment, 133 Nisei in San Francisco were interviewed about their views on the war. When asked about their course of action upon a declaration of war, 17% of males said that they “would volunteer at once, 40% would wait for the draft, 17% would fight in case of invasion only, 14% did not know, and 5% would not go under any circumstances” (72-73). Quotes by many respondents illustrate a fundamental allegiance to the U.S., with only a few even mentioning Japan explicitly in their answers. Of the female participants, 69% said “that they would actively and morally support the United States in case of war,” directly expressing this same allegiance and sense of belonging in explanations of their position (74).

Although raised by immigrant parents, the U.S.-born Nisei still fundamentally identified with American society and culture at large. Their sense of identity reflected their legal citizenship, both of which classified them as just as American as citizens of any other racial/ethnic background. However, by emphasizing their ancestral links to the Japanese enemy, the government made a jarring, subordinating distinction between them and non-Japanese citizens. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Akiko Kurose, who was school-aged during the attack and subsequent Japanese internment, was accusingly associated with the Japanese attackers by her teachers and schoolmates. In a 1997 interview, she described the conflict this created for her identity:

“I no longer felt I’m an equal American, that I felt kind of threatened and nervous about it….And so it became a very emotional time, and my Japaneseness became very, very prominent to me. It was that I became very much aware of my Japaneseness. Not in a real positive way, but kind of a scary way, or, and almost like… ‘Why?!” (Akiko Kurose, 1997)

Kurose goes on to say how her immigrant parents suspected that something would happen to them since they were not citizens; none in the family, however, conceived that the American-born children would be equally affected. The internment of the Nisei reduced them to second-class citizens and rattled their American identities, raising difficult questions about the meaning of American citizenship for them. In turn, this challenge to their identity greatly altered their conceptions of the nation they called home. In a September 3, 1943 journal entry written from within a camp, Richard Nishimoto identified the Nisei around the age range of 18-23 as being “particularly outspoken in expressing their resentment and bitterness toward America and Americans” (18). In his attempt to explain the intensity of this group’s outrage when compared to older Japanese experiencing the same internment, Nishimoto cites Everett V. Stonequist’s The Marginal Man to identify how the experience forced a group of people who were developmentally too young to be “‘race-conscious” to suddenly become extremely aware. This awareness of their “Japaneseness,” as Kurose called it, came with a startling confrontation with the racial distinctions in their society that assigned them “inferior status” (20). At the time of internment, the Nisei were still in the process of exploring and solidifying their conceptions of identity, society, and the relations between the two; the internment undermined this process, allowing them no time to adjust to their newfound racial awareness or to reconcile its relation to society. As a result, their relationship with their nation was forever changed.

After their time in the camps, most of these Nisei had only paltry, if any, communities to return to. As shown by a table of San Francisco’s racial/ethnic population over time created by San Francisco Genealogy, the internment greatly set back Japanese population growth. In 1950, the Japanese population was only about 300 people higher than it was a decade prior. Internment dissolved the Japanese population in the city and then only allowed limited repopulation as many Japanese people were purposely relocated to cities across the country during and after the war. The population in San Francisco thus needed years following internment to recover the original population size. From then on, the population grew steadily until it slowed in the 1970’s, with decent growth to just over 15,000 in 2010. Overall, the Japanese population since 1940 pales in comparison to the Chinese and Filipino populations, which grew rapidly over these decades. If not for the disruptions created by internment, perhaps the Japanese population would have seen similar growth.

Internment of the Japanese not only disrupted the population’s steady growth, but limited its future potential by reducing the city space available to Japanese residents returning from camps. In San Francisco and many other western cities, neighborhoods previously occupied by Japanese communities became homes to thousands of African Americans who migrated from the South for the abundance of work generated by the war (Godfrey 1988, 98-100). Thus, Japantown was altered, and its original expanse was no longer available to its former Japanese residents – it was then impossible for the Japanese to reclaim their neighborhood as they had left it. With limited space and a smaller population, the Japanese community’s recovery is now embodied by a much smaller Japantown. What was once comprised of well over twenty city blocks now spans a mere six.

San Francisco’s Japantown in 1940.

Map: by Ben Pease, © 2004

The Japanese internment thus interfered with two essential aspects of Japanese culture in San Francisco and the U.S. at large. On one hand, it damaged the physical neighborhoods in which people lived, making it difficult for Japanese Americans and immigrants to congregate in vibrant communities fostering the development of a blend between two cultures, foreign and domestic. This same blend was even more impaired in the ruptured identities of the Nisei whose place in American society was challenged by the government’s racist suspicions of their loyalty.

This racist functioning of the U.S. government has recurred an embarrassing number of times throughout the nation’s history. In part, existing societal views have provoked this institutional racism, as with the Constitutional legalization of slavery by the Founding Fathers; more importantly, however, such offensive actions by the government have always had great influence in shaping the public mind. When the government continues to discriminate against its citizens, the society it governs follows suits. Government is meant to protect its people, but events like the Japanese internment ultimately leave dangerously divisive scars on racial and ethnic relations within our society.

Notes

Akiko Kurose, interviewed by Matt Emery, July 17, 1997, Seattle, Washington. “Akiko Kurose Interview I: Segment 13.” Densho Visual History Collection, Densho Digital Archive.

“Detailed Asian Population.” 2010. United States Census Bureau: American Fact Finder.

Godfrey, Brian. 1988. Neighborhoods in Transition: The Making of San Francisco’s Ethnic and Noncomformist Communities. University of California Press.

Lange, Dorothea. 1942. “Japanese American boarding up store.” Photograph. San Francisco. Dorothea Lange Collection, Densho Digital Repository.

Lange, Dorothea. 1942. “Posted exclusion orders.” Photograph. San Francisco. Dorothea Lange Collection, Densho Digital Repository.

National Youth Administration Junior Counseling Service. 1941. “The Japanese American Youth in San Francisco: Their Background, Characteristics, and Problems.” Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement records, UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library.

Nishimoto, Richard S.. 1943-1944. Journal. Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement records, UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library.

Pease, Ben. “Detailed Map: San Francisco’s Japantown in 1940.” 2004. Japantown Atlas – San Francisco’s Japantown (Western Addition).

“San Francisco Population: Table 2.” 2014. San Francisco Genealogy.