California Academy of Science

Historical Essay

by Mary Ellen Hannibal

Security camera on "green roof" of new California Academy of Sciences building in 2007.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The California Academy of Science was founded entirely by amateurs. And the contributions of amateurs working at the academy have been fundamental to the working out of one of arguably the most pivotal scientific breakthroughs of all time, the theory of evolution by natural selection.

On April 4, 1853, a group of “seven San Francisco gentlemen,” in the words of historian Theodore Henry Hittell, met and declared their interest in organizing an institution “for the development of the natural sciences.”(1) A report enumerating the reasons for this asserts, “We have on this coast a virgin soil with new characteristics and attributes which have not been subjected to a critical scientific examination.” A quick glance from “the eye of the naturalist” sees “a field of richer promise in the department of Natural History in all its variety than has previously been discovered.” The report hits on three main objectives for establishing a museum of natural history: to elucidate nature in general, to further democracy, and to make money. Revealing the hidden mysteries of nature would contribute to the progress of the age, by their application to farming and commerce. The language of a new and proud imperial democracy permeates the proceeding notes. Science was making our country “the envy and terror of despots everywhere,” and America’s “avenues” of wealth would help spread the blessings of our “free institutions” to the ends of the earth.(2)

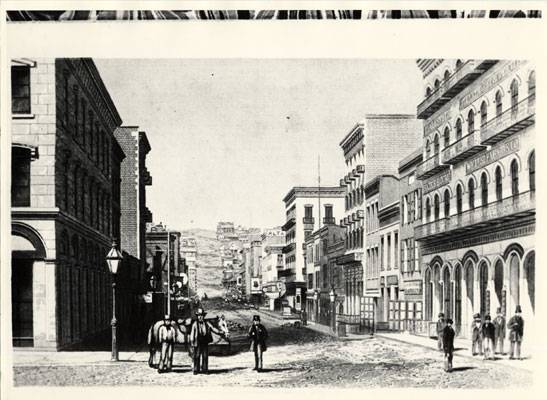

California Academy of Sciences first location at Montgomery Street between 1853-1857.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

It’s worth remembering that abolition was in full swing in the 1850s and much of the United States still clung to slavery, raising the question of whom “free institutions” were really for clearly not everybody. On top of that, while the California Indians were originally abused and their cultures torn apart by the Spanish mission system, the gold rush turbo-charged the stealing of their land and the outright murder of the people. Not a freedom song. As for money, Hittell remarks, “Notwithstanding the flush times . . . there was substantially none for the Academy.” He records the secretary’s notes for the first serial meetings indicating, “No money received at this meeting,” “No cash received,” and the “shorter, though quite as expressive, phrase ‘No cash,’ which had already been used several times.” The academy, however, “was born to live, and it manfully struggled on.”

That the magnificent seven who founded the academy were “gentlemen scholars,” in the words of botanist Barbara Ertter, and not exactly scientists is perhaps evidenced in the way they got going.(3) The first issues of the academy’s proceedings noted the donation of a living owl, “caught near Point Jackson on San Francisco Bay.”(4) The next meeting’s update recorded “that the owl was lost.” An “extensive assortment of plant seeds” was donated by Dr. Albert Kellogg. The happy sum of twenty-two dollars in membership fees was recorded on November 7. On November 28, “Dr. T. S. Anderson presented the Academy with a collection of plants, woods, and shells from Monterey and Santa Cruz and also from Rio de Janeiro, Valparaiso, and the Samoan Islands….Dr. Wm. P. Gibbons spoke about the rocks of Telegraph Hill and the coast of the Bay.”

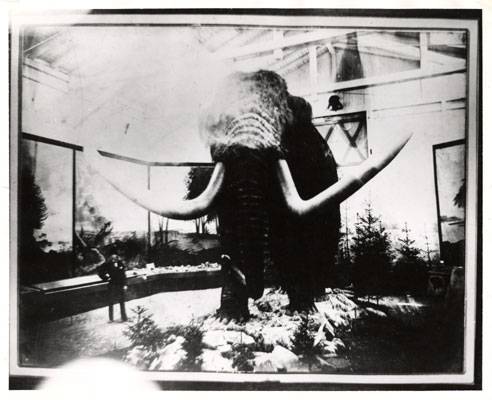

Interior of California Academy of Sciences at California and Dupont Streets between 1874-1890.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

Five of the seven founders bore the title “Dr.,” but only one of them was a practicing physician. The above-mentioned Dr. Kellogg had a pharmacy, but he “was almost too much engrossed with hunting and working over new plants to patiently wait upon customers,” according to Hittell, and he was “particularly fond of trees.”(5) Two of them were affiliated with geological surveys, one was an attorney, and one a real estate broker. None of them was what we would consider today a professional scientist, but this was not unusual in the early days of natural history museums.

The academy founders met weekly in a rented room and initially published their scholarly findings in local newspapers. In 1855, the library of the academy totaled sixty-five books, and all the curators shared a single cabinet. The road to professionalism was very gradual, and overall, the gentleman and gentlewoman scholar model persisted well into the early decades of the twentieth century. Women were expressly welcomed in a motion initiated by Dr. Kellogg in the academy’s first year: “Resolved, as the sense of this society that we highly approve of the aid of females in every department of natural science, and that we earnestly invite their cooperation.”

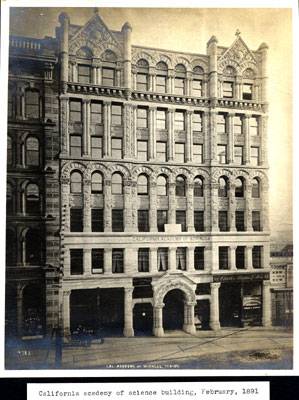

California Academy of Sciences on Market Street, Feb. 1891.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

As the institution evolved, its identity reflected, influenced, and was intertwined with the births of the University of California, Stanford University, state and federal agencies including the Geological Survey and the Forest Service, and advocacy organizations like the Sierra Club, the Sempervirens Fund, and Save the Redwoods League. Dr. Hans Hermann Behr brought the first whiff of true professionalism to the entity, joining the ranks in 1854. An aristocrat trained as an entomologist, a friend of Alexander von Humboldt, Behr made his mark as a botanist. His 1884 monograph Synopsis of the Genera of Vascular Plants in the Vicinity of San Francisco, with an Attempt to Arrange Them According to Evolutionary Principles in fact explains the concept of adaptation and speciation more clearly than many contemporary attempts. New species arise out of older forms, a process that “takes place by the individuals adapting themselves to external conditions, brought on by gradual geological changes, and it is astonishing what a variety of differences can grow out of the same old stock.” Behr tells us that adaptations will continuously emerge “because in this world changes are constantly going on. There is neither pause nor return.” The tone of his day and the bridge he was helping to build poke through the text as here he completes his thought: “The Creator never repeats himself.”(6)

This last bit is worth taking special note of: the ability to distinguish the “new” from the previously discovered. The amateur botanists at the academy were aware that the California flora was special and unique and that they had a fantastic new panoply of species to introduce to science. But with so few publications with which to reference their findings, and with virtually no authority upon which to base their declarations of what was what, they were kind of stuck. East Coast and European scientists, considering the academy crew amateurs and upstarts, resisted species designations coming from California. But in this they were not always quite on the up and up. As Vladimir Nabokov wrote in his poem “On Discovering a Butterfly”: “I found it and I named it…and I want no other fame.”(7)

Naming new species was and continues to be the natural sciences equivalent of the Hollywood handprint, and those snobby professionals willy-nilly named the California species themselves. The academy battle for scientific authority went on for decades and finally received a critical blessing from Asa Gray. Gray famously founded the herbarium at Harvard University, and he was a friend and critical supporter of Darwin’s. “It had been the custom of some Eastern men to describe all sorts of California plants from any kind of specimens, without ever having seen them grow,” Hittell wrote. “They had not infrequently received credit which should have remained in California.” Gray’s encouragement probably helped bolster botany as the most vibrant discipline at the academy in its early days.

Natural Theology

Asa Gray is also an interesting figure in the shifting definitions of and relationships between the amateur and the professional. Throughout the nineteenth century, botanizing was all the rage, an activity undertaken by hundreds of thousands of people of all ages, male and female, rural and urban. It’s hard to imagine now, and if plant-focused citizen science projects today ever reach the historic numbers of hobby botanists, we will be in good shape (as long as they deliver their data to scientifically vetted databases). Botany was vaunted as an activity good for body and especially for soul; it was looked upon as a means to studying God’s creations. Gray was probably Darwin’s most important supporter in the United States, but he also held to the conviction that plant life reveals divinity. Quoting Matthew 6:28 at the opening of his textbook Botany for Young People—“Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow”—Gray put a fine point on it: “Christ himself directs us to consider with attention the plants around us.” In general he supported the idea that natural selection and adaptation are part of God’s design. Hewing to what’s called natural theology, some botanists were very specific about how plant life reflected, as Elizabeth B. Keeney puts it, “God’s continual orchestration of the world,” citing, for example, its transformation of the environment to make it habitable. One botanical writer advocated gratitude for “the wisdom of the system.”(8)

Gray eagerly enjoined armies of amateur botanists who supplied him with specimens and treated them as colleagues, though not without a personal interest. He was busy compiling a hugely ambitious Flora of North America, and among other things, he needed the California information to fill it out. It behooved him to maintain positive relations with the crew at the academy. Gray also cultivated the steady flow of California species identifications from the eventual California Geological Survey to Harvard, where the first set of botanical collections made by the survey were deposited at the Gray Herbarium; they remain there to this day. (A duplicate set established the University of California’s herbarium.) Gray thus paradoxically undermined the academy’s efforts at “autonomous publication” and contributed to the premature curtailment of the Geological Survey itself by the California legislature, one argument against it being that it was serving Harvard more than the state itself.(9)

Despite Gray’s interest in its contributions to the science (and thus religious implications) of botany, the survey was established for less lofty reasons. The gold rush was just that, hard and quick, over fast—like the saying has it, a flash in the pan. By 1860 the emergent state of California was looking for new ways to harness and monetize its natural resources and thus proposed a geological survey on the model of many older states, as “a hallmark of enlightened state administration…. The means whereby exploitable resources might be cheaply located and advertised to would-be investors.”(10) The survey was dispatched to map the state and inventory its plants, animals, rocks, soils, and minerals. It chugged along in fits and starts, always begging funding from the California legislature, until the plug was pulled on it in 1868.

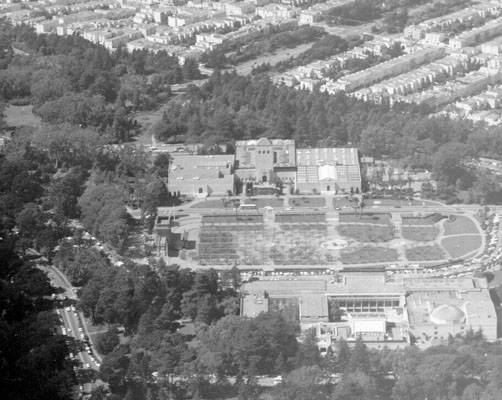

Aerial view of Golden Gate Park looking northwest over bandstand, De Young Museum, Steinhart Aquarium and the Academy of Science, 1970.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

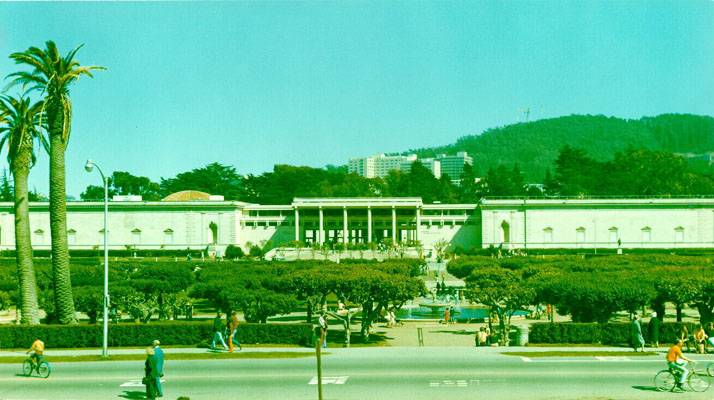

The California Academy of Sciences building in Golden Gate Park, c. 1970s.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

The academy had close intersections with both the survey and the nascent university system as well (which it still does), and in those early years there was something of a push-me-pull-you between the institutions. First was a tussle over who got the specimens from the decommissioned survey—the university did. The academy’s ranks were at somewhat of an ebb at this time, and the regents of the university actually proposed incorporating the academy into its own, newly formed ranks. The director of the academy at the time, James Cooper, who had been a survey zoologist, fulminated against being “swallowed up in that Asylum for rebel Professors.” (And the 1960s were almost a hundred years away!)

True Believers

The academy established itself at the biggest juncture ever in the history of the natural sciences, surely, and some would say in the history of all human intellectual life: at about the time that Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection humbly began to disrupt centuries of belief about life on earth. Founded in 1853, the academy was a mere five years behind the presentation of Darwin and Wallace’s papers on the subject of natural selection at the Linnaean Society. Included in the papers was an 1857 letter from Darwin to Asa Gray, elucidating his ideas. Darwin’s biographer Janet Browne says Gray was “by far the most prominent botanist in the United States, and on an intellectual par with Louis Agassiz, his zoological counterpart at Harvard,” and paints a picture of Darwin venturing his ideas before the august Gray with trepidation. Darwin worried that the devout Congregationalist Gray would “despise me” when he shared his ideas, but Gray encouraged Darwin: “Can you get at the law of variation?”(11)

Asa Gray teamed up with Joseph Hooker, the botanist to whom Darwin had first confided his ideas about “transmutation” ten years earlier, and the two scientists introduced the work of Darwin and Wallace to the Linnaean Society. Browne says they were subsequently “relieved to be able to talk about natural selection in public.” The protracted tension Darwin and Wallace’s ideas would create in science began right here. Gray outlined natural selection at a Harvard University science club meeting in 1859. He confessed to playing the provocateur, “maliciously to vex the soul of Agassiz with views so diametrically opposed to all his pet notions.” Agassiz had become one of the earliest honorary members of the California Academy of Sciences, upon his acceptance of this position in 1854, Hittell writes, “requesting to be furnished with all the documents concerning the discovery of the viviparous fishes.”(12) As Gray was keen on getting the new flora from California, Agassiz was keen on the fauna.

Browne says that in 1858 and 1859 Agassiz “dominated American intellectual life. He was well known as believing that all living beings, including humans, were created by divine fiat. Species were thoughts in the mind of God, he announced in his Essay on Classification.” Agassiz reasoned that no classification system could be possible if species were always changing; he opined that since what would eventually be called ecology is a series of densely intertwined relationships, species must be constant. Darwin greatly admired Agassiz but this idea of the immutable thoughts of God was “utterly impracticable rubbish.”(13)

Agassiz’s antipathy and Gray’s enthusiasm toward Darwin probably added some tension to faculty meetings at Harvard. But both men continued to be highly esteemed and their influence felt all the way to California. In 1872 Charles Darwin was elected an honorary member of the academy (a distinction conferred in absentia—he never visited here). The same year, Agassiz addressed the academy, speaking to an eager crowd big enough that the meeting had to be held in a venue more capacious than the academy’s Clay Street digs. Agassiz praised the academy for hewing to more lofty concerns than the frantic gathering of gold and emphasized California’s duty to increase scientific knowledge.(14) It was no small matter that America’s premier intellectual stamped the mission of the academy with his imprimatur. Agassiz took the academy

Rebuilding the Academy of Science in 2005, UCSF at Parnassus Heights in background.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Looking down on the fish tank from the 3rd floor, 2007.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Looking up through the same fish tank from the pedestrian tunnel beneath it.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Notes

1. The primary source for information regarding the inception of the academy is Theodore Henry Hittell’s The California Academy of Science: 1853–1906, the manuscript of which was among the treasures rescued by Alice Eastwood from the academy after the 1906 earthquake and right before the fire destroyed the building. Its current format, published by the academy in 1997, was prepared by Al Leviton and Michele Aldrich, who spent ten years verifying Hittell and annotating his document.

2. Theodore Henry Hittell, The California Academy of Sciences: A Narrative History (San Francisco: California Academy of Sciences, 1997), 489.

3. Barbara Ertter, “People, Plants, and Politics: The Development of Institution Based Botany in California 1853–1906,” Cultures and Institutions of Natural History (San Francisco: California Academy of Sciences, 2000). Ertter is the semiretired curator of western North American flora at the University of California, Berkeley.

4. This species name is currently “unaccepted” by the World Register of Marine Species—I’m trying to figure out what that means!

5. Al Leviton, emeritus curator at today’s academy as well as director of its scientific publications, told me that Kellogg was “a botanist of the first order for his time and he described many new species.”

6. H. H. Behr, Synopsis of the Genera of Vascular Plants in the Vicinity of San Francisco, with an Attempt to Arrange Them According to Evolutionary Principles (San Francisco: Payot, Upham, & Co., 1884), 8. I uploaded this text and printed out a PDF of some of it via the Biodiversity Heritage Library, part of the Internet Archive, which makes millions of pages of historical text available to all of us: SO COOL.

7. Nabokov was himself a citizen scientist. With no formal training, he yet made significant contributions to lepidopterology that are even today shedding new light on earth history. He ran the lepidoptera collection at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology while teaching literature at Wellesley in the 1940s.

8. Elizabeth B. Keeney, The Botanizers: Amateur Scientists in Nineteenth Century America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992), 102-9

9. Ertter, 216, quoting William H. Goetzman, Exploration and Empire: The Explorer and the Scientist in the Winning of the American West (New York: Knopf, 1966), 355

10. Ibid., 207, 209.

11. Browne, Charles Darwin: The Power of Place, 38

12. Hittell, 29.

13. Brown, Charles Darwin: The Power of Place, 50-52.

14. Hittell, 146.

Excerpted from Citizen Scientist: Searching for Heroes and Hope in an Age of Extinction by Mary Ellen Hannibal. Copyright © 2016 Mary Ellen Hannibal. Published with permission of the publisher, The Experiment.