Maiden Lane and the Pot-holes of History

Historical Essay

by Peter Field

This article is part of a research project by the author tracing the history of San Francisco’s Tenderloin District from its origins in the 1840s to the present.

I

Several pages in Herbert Asbury’s and Oscar Lewis’ wonderful books The Barbary Coast(2) and Bay Window Bohemia(3) trace what they presented as the history of Morton Street, one of 19th century San Francisco’s notorious brothel alleys, now a chic shopping street called Maiden Lane that runs east two blocks from Union Square. But are Asbury’s and Lewis’ accounts, which were published respectively in 1933 and 1956, the actual history of Morton Street? Or are they another addition to the corpus of San Francisco urban legend? In particular, Asbury’s stories about this street have been repeated so often in books,(4) in articles,(5) on web sites,(6) and by tour guides(7) that his version of Morton Street’s past has achieved a life of its own, even among historians, and the dissemination of its story has been widespread. Who among the legions of San Francisco history enthusiasts hasn’t read Asbury’s and Lewis’ books?

Asbury wrote that Morton Street had the worst cribs (i.e., the cheapest and most disease ridden brothels)(8) in San Francisco, and that it was “thronged by a tumultuous mob” every night. He also said the prostitutes leaned from their open windows “naked to the waist, adding their shrill cries of invitation to the uproar, while their pimps haggled with passing men and tried to drag them inside the dens.” He went on to say, “If business was dull, the pimps sold the privilege of touching the breasts of the prostitutes.” In addition, he wrote that the Morton Street cribs were popular “partly because the police seldom entered the street unless compelled to do so by a murder or a serious shooting or stabbing affray. Ordinary fights and assaults were ignored.” Asbury also reported that Morton Street prostitution was diverse: “These dens were occupied by women of all colors and nationalities; there were even a few Chinese and Japanese girls.”

Moreover, he asserted that when “a respectable woman came through Morton Street on a slumming tour . . . the prostitutes greeted her with ribald jeers and curses, and cries of ‘Look out, girls, here comes some charity competition!’ and ‘Get some sense and quit giving it away for free!’ ” He indicated that their prices ranged from twenty-five cents to a dollar and he summarized the careers of two of the street’s more interesting inhabitants. One of them was a prostitute turned madam named Iodoform Kate who bought about a dozen brothels on Morton Street in “about 1895 . . . and after a few years she retired with a comfortable fortune.” The other one was Rotary Rosie, “an appellation which perhaps sufficiently described her,” who “fell in love with a student at the University of California” a year or so before the earthquake and fire of 1906. According to Asbury, she would service him and his fraternity brothers for free on the condition that they would read poetry to her for half an hour. Her ambition was to quit prostitution and get a college education. He ended his account by stating, “Except for a brief period in 1892, when they were closed as the result of a crusade by the Civic Federation, the unholy dens in Morton Street maintained a continuous existence for more than forty years. They were finally destroyed in the conflagration of 1906 and were not rebuilt, principally because the land on which they had stood was too valuable for business purposes.”(9)

Twenty-three years later, Lewis wrote another brief version of Morton Street’s history. He apparently agreed with Asbury that it sheltered “harlots of all nations—including French, Chinese, Negroes, Mexicans, and Americans,” and that the street “continued to boom until the entire area was laid waste by the fire of 1906.”

Lewis also listed several features of the alley not mentioned by Asbury, including that it was also called Iodoform Alley. “It was the hangout, too, of pickpockets, dope peddlers, and thugs of every description.” Moreover, “it was scrupulously avoided by the town’s respectable women, for to set foot within its confines was considered a serious breach of decorum. To guard against that possibility there was usually a policeman stationed at each end of the street charged with warning away the curious.” Lewis also described a real estate scheme hatched by political boss Abe Ruef after the turn of the century to buy all the Morton Street brothels. He was said to have done this by initiating a months-long cleanup campaign in which all the brothels were closed down, forcing the property owners to sell their holdings to Ruef’s agents, who then reopened the brothels under his ownership.(10)

But are these accounts credible? Asbury’s stories sound anecdotal because they were, as he was the first to admit when he prefaced his extensive bibliography by stating, “A great deal of the material in this book came from the personal recollections of old-time San Franciscans and has never before been published.”(11) None of these individuals were identified, but given The Barbary Coast’s 1933 publishing date, they would have been between 55 and 82 years old if they were presumed to be least 18 when they were witnessing or participating in the episodes they recounted. In other words, these memories would have been recollected from events occurring 37 to 64 years before the interviews.(12)

Moreover, some of these anecdotes are frankly questionable. One example is the reaction of Morton Street prostitutes to the presence of respectable women. Not only is it difficult to imagine a 19th century woman of any respectable class walking through Asbury’s version of Morton Street during its brothel years, but a review of several hundred newspaper articles (13) as well as other primary sources found only two incidents of this, and these reports said nothing about them being taunted.

One account was recorded by Harriet Lane Levy in her memoir, 920 O’Farrell Street,(14) in which she recalled her Saturday night walks with her father when they often went along Dupont where it crossed Morton Street.

“One side was completely occupied by one-storied cottages . . . each with a short flight of steps and a bay window. In each embrasure in back of the center pane a woman sat . . . her cheeks were painted, her eyes glazed; she wore a bright colored Mother Hubbard gown. (15) One sat in every window as far as the eye could see down the alley toward Kearny Street. They sat motionless, looking straight ahead . . . One night, a political procession was marching on Kearny Street. We were on Dupont Street when we heard the band. ‘Hurry, hurry,’ I begged, and Father rushed me through the alley . . . ‘You old fool, take that child away from this,’ I heard behind me and trembled.”(16)

This is the only account that has come down to us today of a prostitute yelling at a female walking down Morton Street. (17) But in this instance, she wasn’t yelling at Levy: she was trying to protect her by upbraiding Levy’s father for exposing her to a brothel alley.

While Lewis’ stories sound less anecdotal and implausible than Asbury’s, he didn’t cite any sources at all in Bay Window Bohemia, perhaps intending the book as another “informal history,” as Asbury subtitled his own work. But the lack of citations leaves a conundrum: are we to accept the account of an historian of Lewis’ stature ex cathedra?

Asbury’s and Lewis’ amusingly written anecdotes aside, a review of over four hundred newspaper articles and items, advertisements, census sheets, Sanborn fire insurance maps, and other primary sources (18) found evidence to support only the following assertions: prostitution proliferated on this street for a period of time, the prices ranged from twenty-five cents to a dollar, and the prostitutes sat in their windows to advertise their availability. And if Asbury’s description of the street being “thronged by a tumultuous mob” is interpreted to mean most of the brothels’ patrons had been drinking, then source materials also show that their customers were generally intoxicated. (19) In addition, evidence was found to support only one of Lewis’ assertions: “pickpockets, dope peddlers, and thugs of every description” did in fact populate Morton Street during its brothel years. So, how did Morton Street become a brothel alley, and what actually happened there?

II

The street’s original name was St. Mark’s Place, though when and why the street was first named are obscure. (20) Its development occurred in the decade before the Civil War in a small valley just east of the big sand hill covering the block that later became Union Square. (21) The first hint of the street’s existence was found on a topographic map of San Francisco from the U.S. Coast Survey of 1852, which showed one structure along the line of the future street’s two-block length, standing about equidistant between Kearny and Dupont Streets, (22) though as yet there was no actual thoroughfare. Further development of the alley must have commenced within a year or two of the survey, for the earliest finds of mentions of this street were in real estate and rental listings in newspapers in 1853 (23) and 1854. (24) The first rooming house ad for the street appeared in March of 1855. (25) The first city directory listings for St. Mark’s Place were in 1856. There were only 24 and they were innocuously residential, with some listings showing prosperous sounding occupations such as physician and business owner. (26)

A map of an 1857 topographic survey of San Francisco shows St. Mark’s Place was graded, the lots were leveled, and much of its two blocks were developed. (27) The 1858 city directory showed the number of listings had almost doubled to 42. (28) During its first 20 years, both blocks seem to have been developed in tandem because the increasing number of addresses on each block remained roughly equal. (29) A tally of the resident’s occupational listings taken from the city directories of 1856 through 1869 showed that blue collar occupations tended to congregate on the block closest to Kearny Street, which was becoming a fashionable shopping district, while white collar occupations tended to congregate on the block closest to Stockton Street where a middle and upper class residential neighborhood was developing into what became Union Square during the Civil War. This mix of middle and working class families and single blue-collar workers on the two blocks of St. Mark’s Place continued undisturbed until the brothels moved in. (30)

St. Mark’s Place continued to grow. The 1859 directory listed 66 individuals living there, again with unremarkable occupations, with just one exception: Ephraim S. Tyler was listed as a “clairvoyant physician” at 47 St. Mark’s Place. The 1860 city directory showed almost the same number of listings as the year before, (31) distributed among approximately 34 addresses, including a German school that opened on the corner of St. Mark’s Place and Stockton Street. (32) The year was chiefly memorable for the residents success in getting a street light installed on this corner, (33) and of the planking of the intersection of Dupont Street and St. Mark’s Place. (34) The U. S. Census of 1860 did not show any prostitution in the area. (35)

Until 1860, Market Street began at the Bay and ended a few blocks later at a giant sand hill just past its intersection with Kearny and Third Streets, a half-block from the beginning of St. Mark’s Place. In July, the building of the Market Street Railroad from the Bay all the way out to Valencia and then to 25th Street (36) opened Market Street and its surrounding neighborhoods to more accelerated development. Until then St. Mark’s Place had been a peaceful two-block residential alley with little to disturb its quiet. The following year, easier accessibility increased the street’s new city directory listings by almost a third. (37)

The earliest reports of crime on St. Mark’s Place were found in 1857. There were just two incidents, (38) and although they were relatively serious, no further mentions of criminal activity were found until April 1862 when Michael Hardigan, brother of a plasterer at number 28, was stabbed by a street contractor named Fitzpatrick in a St. Mark’s Place grocery store. (39) In August Manuel Garcia was arrested, probably in the same store, while trying to rob the till while the proprietor was dozing. (40) And Mrs. Mary Garvey was arrested for drugging and robbing Andrew Crotty, a fellow resident in their St. Mark’s Place lodging house. (41) This was also the year a Miss Buchanan appeared in the San Francisco city directory as having furnished rooms at 17 St. Mark’s Place. (42) But the listing was only a front, for the house had the distinction of being the street’s first brothel.

Prostitution came to St. Mark’s Place much the same as other businesses as they followed San Francisco’s southwestern growth. Before the 1860s, San Francisco brothels were mostly located in the streets and especially the alleys north of California Street around Portsmouth Square and Chinatown, and in the Barbary Coast. After Market Street was opened beyond Kearny and Third Streets, they expanded south across California Street along Kearny and Dupont into the area east of Union Square. There was even a house of assignation on the east side of Stockton between Sutter and Bush. (43) Most brothels were located in alleys instead of regular thoroughfares, primarily because of a quasi-official municipal policy of containment and concealment. This policy was continued south of California Street in alleys like St. Mary’s Place, Belden Place, and St. Mark’s Place. (44)

The earliest mention of Miss Buchanan’s brothel to be found in the press was an 1863 Sacramento Daily Union article reporting that Nellie Jones, a 25 year old woman living on St. Mark’s Place, died from burns received on January 16th when she fell asleep reading a newspaper which caught fire from a nearby candle and ignited her dress. (45) The more sedate Alta discovered two of her aliases, and corrected an earlier story by reporting her real name as Ellen Rowland. It also stated she was a prostitute, published the address of the house, and described the incident in greater detail than the Union article. (46)

In June there was a report of a man named Gorman, arrested in a St. Mark’s Place brothel for threatening the madam with a pistol. (47) The following year the Union reported the kidnapping of a prostitute from St. Mark’s Place. She was taken in a carriage to the then outlying neighborhood of Mission Dolores and raped before managing to escape. (48)

The brothel closed down after around two years, as shown by a May 8th, 1864 Alta advertisement for an auction of mirrors and elegant rosewood furniture at that address. (49)The luxurious furnishings suggest that St. Mark’s Place’s first brothel was a parlor house rather than one of the cribs (50) Asbury said was located on this street. Number 17 then became a legitimate rooming house. (51)

The next reports of prostitution on St. Mark’s Place were found in several March, 1869 newspaper articles five years after Kate Buchanan’s parlor house closed, when a hack driver was shot trying to collect a fare from “a party of demi mondes” after he drove them from their brothel on St. Mark’s Place to the Cliff House and back. (But the hack driver, a tough breed in those days, took the gun from the man who shot him – probably their pimp, beat him over the head with it, and hauled him off to the police station, where he pressed an assault charge against him . . . and did this with a gunshot wound to his own head.) (52)

This marked the start of a transition from residences to brothels that occurred on St. Mark’s Place between 1869 and 1881. Some of its residents had lived there since the mid-1850s, but 1869 was when they began to move away. The transition was seen in an advertisement that year announcing the auctioning of the contents of the family home at number 117, (53) the first of a series of similar ads to appear over the next decade. The Franklin brothers, two pawnbrokers who moved to number 109 with their families around 1859, (54) were another example of residents who began to leave. John Franklin’s wife and son both died within a month of each other in 1870, (55) and the brothers sold the house for $5,000 in 1872, (56) probably alarmed by the increasing numbers of brothels on the street. By 1876, Frederick Raue of number 35 was the last of the old time St. Mark’s Place residents still listed there, but he, too, moved away after that year. (57)

The Board of Supervisors voted to change St. Mark’s Place’s name to Morton Street on May 24, 1869, (58) the same year the brothels began to move there to stay, which is why Morton Street’s name was always associated with prostitution in the minds of San Franciscans. The renaming was probably in honor of, if not petitioned for by the founders of R. & J. Morton, one of San Francisco’s largest drayage firms, (59) who built the Morton Building, a swank hotel on Post Street between Kearny and Dupont with its rear on St. Mark’s Place. (60) Parts of the building were also leased to government agencies, particularly those in the legal professions. Thus for a time in the 1870s one of the city’s deputy sheriffs offices, located on Morton Street in the rear of the building on the first floor, looked across the street at several brothels, with the women in their windows. (61)

Morton Street started attracting other marginal and disreputable businesses in 1870, the year after the brothels return. For example, an astrologist named Madam Buck moved to number 105, announcing office hours from 10 in the morning to 9 in the evening. (62) A concert saloon at the corner of Kearny and Morton Streets was reported on June 15th as having just been closed. (63) It was called the Tammany and its patrons loitered outside the door while making lewd remarks to passing women and otherwise disturbing the peace. (64)

The 1870 census listings (65) showed the 2nd precinct of the Eighth Ward (which included Morton Street and the area east of Union Square along with most of what would later be known as the Tenderloin) as having ten brothels – two of them on Morton Street, seven of them on nearby blocks, and one about three blocks away on O’Farrell. (66) Data from this census don’t support Asbury’s and Lewis’ assertions concerning the diversity of age and race they claimed characterized the prostitutes of Morton Street. A tabulation of the census entries showed there were 19 prostitutes and five madams distributed among nine dwellings on or near Morton Street. Two-thirds of the prostitutes were between the ages of 18 and 24 with just two getting on in years at ages 36 and 40. This meant that the odds were about 9 ½ to 1 against the two older prostitutes being located in either of the Morton Street brothels. Hence, the women in those two houses were probably too young for them to have become “the worst cribs in San Francisco.” (67) As for race, 17 were white and two were black. Ten were born in the United States and the other nine were born in Western European countries. This also made the odds about 9 ½ to 1 against the two Morton Street brothels housing the two black women. Thus, the prostitutes’ ages and races listed in the 1870 census records showed that the two brothels on Morton Street probably hadn’t achieved the diversity described by Asbury in The Barbary Coast or by Lewis in Bay Window Bohemia, or at least not at that time.

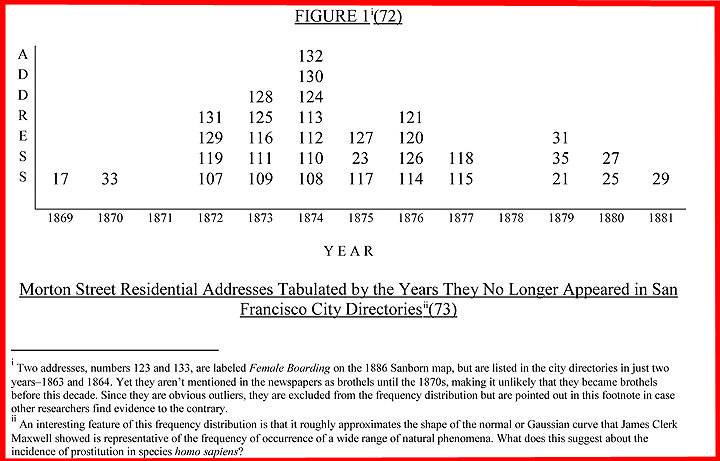

The time frame of the movement of brothels onto Morton Street can be inferred with greater precision by looking at the 1886 Sanborn map (68) addresses labeled “Female Boarding” (69) and noting the years in which each address stopped appearing in the city directories. (70) If we assume that the years in which these addresses stopped being listed represent the years they became brothels, a startlingly clear picture emerges: number 117 opened as a brothel on the upper block of Morton Street next to Union Square in 1869, and number 33 opened the following year on the lower block. Beginning three years later in 1872, more brothels opened on upper Morton Street with increasing frequency, the openings peaking in 1875, and then declining until 1877, when all the residential addresses of that block had become brothels. In 1870, lower Morton Street had only the one brothel at number 33 until five years later when two more opened at numbers 17 (Kate Buchanan’s former parlor house) and 23. These establishments shared the block with the remaining residences until the rest of the residential addresses became brothels between 1879 and 1881.

In other words, upper Morton Street’s residences were replaced by brothels between 1869 and 1877, while lower Morton Street was partially occupied by brothels beginning in 1870 until the remaining residences were replaced by brothels between 1879 and 1881 when there was no longer any room in upper Morton Street. Thus, roughly speaking, in the 13 year period from 1869 through 1881, (71)prostitution returned to Morton Street and took over its two blocks. The actual frequency distribution looks like this:

The transition of Morton Street and other thoroughfares in this area into brothel alleys eventually caused the Board of Supervisors to adopt an ordinance “prohibiting messenger boys from answering calls from houses of bad character.” (74) Business firms wanted to keep their employees, especially younger ones, away from temptations likely to impair their efficiency, or likely to damage the companies’ reputations, and some had standing orders forbidding their employees from doing business at certain addresses on streets such as St. Mary’s Place, Berry Street, Belden Place, Quincy Place, and Morton Street, which were well known as brothel alleys. (75) Another likely reason for these prohibitions was a frequent ruse of the prostitutes during Morton Street’s later years: they would lean out of their windows and snatch the hats of male passersby to lure them inside. (76)

A feature of Morton Street during those years was described by newspapers when they reported that the prostitutes advertised themselves in a special way. Each of the houses had windows on the first floor (77) at the same level of the wooden sidewalks that ran up and down the alley. (78) The prostitutes sat inside the windows with the shutters open to display their availability to customers, (79) the same method used by their sisters in San Francisco’s other brothel alleys as well as by prostitutes in European cities (where this is still done today). Many of the women were in fact from Europe – usually from English or French speaking countries.

Morton Street also changed in other ways. During the 13 years it was being colonized by brothel madams and prostitutes, its remaining legitimate residences were being remodeled into rooming and lodging houses. The street’s one hostelry, the St Mark’s Hotel, was enlarged from a four room hotel to a twelve room lodging house and renamed the Germania. (80) In 1869, reports of fights, muggings, and pickpocketings along the alley began to appear with increasing regularity. Crime was especially frequent in the mid-1870s when the brothels had taken over most of the houses on upper Morton Street. (81) So it’s not surprising that the number of respectable residents fell precipitously between 1872 and 1884, leaving only one residential listing for all of Morton Street, a man named Costello at number 3. Another example of how Morton Street was changing was seen when Tomas Redondo, also known as Procopio, Red Dick, Dick of the Red Hand, Red–Handed Dick, and Tomas Murietta, a well-known killer, cattle rustler, horse thief, and stage coach robber who claimed he was a nephew of the legendary Californio bandit Joaquin Murietta, was arrested in a Morton Street restaurant in 1872. (82)

In the meantime, Morton Street’s respectable residents tried several times to get the city to close down the brothels. The first reported attempt was in 1872, when the number of these houses tripled. The Board of Supervisors was petitioned to “suppress the houses of ill-fame on that street,” because “there are more respectable houses there than others.” (83) The petitioners’ efforts were apparently only partially successful, because the newspapers continued to report incidents involving the prostitutes, albeit fewer of them. (84)

Meanwhile, saloons opened on Morton Street in that same year, like Charlie’s Hot Scotch at number 15. (85) Sarah Jane West and brothel madam Emily Edwards were arrested on Morton Street for fighting, (86) while a Spanish woman named Juan or Juana, who also called herself Lizzie Hall, shot a young man in the shin at her brothel at number 128 after he hit her. The case was continued several times until it was dismissed five weeks later when the shooting victim – one Henry Milton – disappeared. (87) Then there was a report of a Police Commission investigation of Special Officer Lawlor, “accused of levying blackmail on those women along his beat.” (88) However, several prostitutes, including Cummasse Densue and Juana Sobrero (possibly the same woman reported at number 128), both of Morton Street, testified in Lawlor’s defense about his

“uniform attention to business and courtesy towards them; he was paid by each of them from fifty cents to a dollar a week; he never demanded it, but invariably awaited their financial circumstances and pleasure; they paid him freely and voluntarily; he was always on hand when they were in trouble from loafers.” (89)

This last story is significant because Asbury wrote that one of the reasons for the street’s popularity was because police officers seldom ventured there except in the event of a major felony. (90) However, newspaper accounts, such as the one about Officer Lawlor, show that the police – special and regular officers as well as detectives and plainclothesmen – were on or around the two blocks of Morton Street often enough for arrests to be regularly reported, and after 1880 they were reported at least monthly and frequently even more often. There were also times when officers were stationed on the street itself. This was so even though at that time San Francisco had just 104 officers for a population of over 150,000 residents, or one officer for every 1,445 citizens – the lowest of any city in the world according to one report. (91)

Not only was there was a significant police presence, but the most frequent arrests reported by the newspapers weren’t the major felonies listed by Asbury. Instead, they were generally misdemeanors like fighting, soliciting, drunkenness, and vagrancy. More serious crimes were usually minor felonies, such as prostitutes picking the pockets of inebriated customers. (92) Morton Street must have been regularly patrolled by the police for the obvious reason that it was a brothel alley, that is, a potential high crime area, bordered on the east by Kearny Street, which was developing into San Francisco’s main shopping district, and on the west by the middle and upper class residential district around Union Square.

Another reason Morton Street and others like it were regularly patrolled was because of the San Francisco Police Department’s quasi-official policy of containment. For example, on March 2, 1895, Arthur McEwen’s Letter reported “Chief Crowley has been careful to prevent the spread of the residences of the Magdalens throughout the city . . . [but] the Chief of Police is given no credit [by the moral crusaders] for that watchfulness which has preserved the city in general from pollution.” (93) If the police couldn’t eliminate prostitution, which many 19th century thinkers believed to be the case, then they could at least keep the brothels, especially the cribs and the cow yards, out of sight in the alleys of Chinatown, the Barbary Coast, South of the Slot, and the Dupont–Kearny area east and northeast of Union Square. In spite of Oscar Lewis’ claim that police officers were usually stationed at each end of Morton Street’s two blocks to keep respectable ladies from blundering into these alleys, (94) the only time this level of official supervision was actually reported was during several unsuccessful campaigns to close down the brothels altogether.

But even regular police patrols didn’t always keep Morton Street’s denizens under control. In 1873 and 1874, a rising number of violent incidents and other problems plaguing Morton Street (95) apparently provoked its second police crackdown. This was suggested by a Chronicle description of the prostitutes’ method of evading capture: “Within the past few days, in a number of the houses, doors have been made, leading to the adjoining houses through which the inmates pass when in danger of arrest.” (96)

By 1874 the class of prostitutes on Morton Street was deteriorating. In February, the trial testimony of two high class swindlers established that one of them, Naphthaly, often visited the brothel at number 131, operated by Ida Clark, in addition to brothels on Dupont Street. The witness, a police officer whose beat included this area, testified that all the houses visited by Naphthaly had “the lowest class of women who reside in such houses,” including several on Morton Street, such as number 110 which was run by a Frenchwoman named Clement, number 107 which was run by Bertha Cahn, and another which was run by Annie Blaine. (97)

Further evidence of decline was found in December 1874, when the police arrested two Morton Street prostitutes for stealing from their customers. This was the earliest instance of this type of misdeed to be found in reports of Morton Street crime, and it suggested that prostitutes of a lower class were establishing themselves there. One of them, known as the Tomboy, was detained for stealing $80 from a customer, but was discharged after the victim disappeared. (98) The other woman, an independent operator named Mary Daily, was arrested on the complaint of Robert L. Hockman, a recent arrival “from one of the interior counties,” when she lifted $60 from his pockets. (99) This kind of theft was reported on Morton Street with increasing frequency over the following decades.

By 1875, fractional house numbers (such as 112¾) began to show up in the San Francisco city directories as Morton Street addresses (100) when property owners subdivided these former family dwellings in order to maximize rental income. A former single family residence might be subdivided into two, three, or even four units, each of them housing a brothel or renting rooms nightly to prostitutes.

A decrease in crime on Morton Street resulting from the raids of 1874 and lasting into 1876 was suggested by the finding of only two newspaper items mentioning Morton Street during this period. One was a mysterious ad in the Chronicle: “JOSIE-MARY WANTS TO SEE YOU-105 Morton Street.” (101)

The other was a report of the arrest of a former Morton Street brothel owner for procuring underage girls. His name was Martin Mace, and he furnished an example of how the management side of the brothel business worked. He was indicted by a San Francisco Grand Jury in 1874 for grand larceny when he was known as John Martin Mace. (102) A former sailor, he apparently purchased one of the brothels on Morton Street (103) after being paid off for sinking a ship in an insurance swindle. He made money in his new venture, and learned to dress and act like a gentleman. He managed to marry a girl from a respectable family, but then moved her into the house and turned her out as a prostitute. Later on, she was rescued by a wealthy bachelor who “happened” into the brothel. After hearing her story, the gentleman arranged to help her escape and sent her back East. Mace filed a $10,000 lawsuit against the bachelor and his associates who helped him rescue the woman, and used this to extort a considerable amount of money in exchange for dropping the suit and its attendant notoriety. (104)

In 1877, the number of city directory listings indicating respectable addresses on Morton Street had shrunk to 38, with nearly all of them at the Germania Hotel at number 25. (105) This was where an unemployed German carpenter named William Shick committed suicide that year by shooting himself in the head while drinking heavily in his room. (106) In July, the police staged a wholesale raid of the Morton Street brothels for the first time in three years. This raid, according to the Sacramento Daily Union, “captured a large number of the inmates, who had been making themselves more conspicuous than the law allows.” (107) This statement suggested what many of the paper’s readers already knew or assumed, that the police had permitted the brothels on Morton Street and elsewhere to operate, but only if the they didn’t attract too much attention. (108)

But by 1878, there was little evidence to suggest that prostitution on Morton Street had been eliminated or even much diminished, in spite of the police crackdown the previous year. However, the police do seem to have reasserted their control of the prostitute’s behavior since the only prostitution-related arrest that year was when a man was taken into custody merely for tossing firecrackers into one of the Morton Street brothels. (109)

In 1879 the police began to once again lose their grip on the situation on Morton Street, as the press reported a growing catalogue of tragedies and crimes. (110) For example, former police officer Edward P. Snively got drunk and committed suicide by shooting himself in a Morton Street brothel. (111) Several months later Michael Barrett was arrested for stealing $83 and some jewelry from a Morton Street prostitute named Louisa Dawson. (112) The following month a police officer was badly beaten by four men who entered a Morton Street brothel where the officer was investigating a reported theft of $500 from a customer. (113) Then there was a man who was arrested in one of the brothels for biting the nose of one of the prostitutes. (114) When the Police Commission investigated the alleged extortion of prostitutes by police officers, one officer admitted to the Commissioners that he had “been investigated before by the Commission for unofficer-like conduct in a house of ill repute on Morton Street.” (115)

Also of interest was an 1879 Chronicle report describing in great detail a masked ball and its attendees at the California Theater. The beautiful vivandiere (116) costume of Miss Lillie Lorraine of 205 Post Street was mentioned near the end of the article. Though there were dozens of participants listed, hers was the only one that included an address, (117) a not-so-subtle way of identifying her as a prostitute working at a parlor house run by Diamond Carrie Maclay. (118) This building, located next door to posh Marchand’s restaurant, (119) had a covered second-story passageway that ran across the backyard to the rear of 108 Morton, doubling the size of her business. What this meant was that Morton Street still had at least some vestige of higher class prostitution, even if it was only the rear entrance.

This was also the year the very respectable Olympic Club moved into the remodeled upper floors of the old Morton House hotel (now O’Connor, Moffatt & Co.’s dry goods store) with the club’s parlor windows looking down at the brothels on Morton Street, as did the club’s billiard and chess rooms on the floor above. (120) One wonders what the members made of this view. Did they speculate on the street’s activities between billiard and chess games? (121)

1880 was another busy year on Morton Street. Police Officer Thomas Price arrested Morton Street prostitute Victorine Bird for being an inmate of a brothel. She had requested a jury trial and the charge was dismissed when some of the jurors twice failed to show up and her lawyer demanded that the officer appear as a witness. The Chronicle article pointed out that Officer Price, whose beat included Morton and Dupont Streets, was also being sued by another prostitute’s husband for the return of property she had signed over to Price. He arrested Bird again on the same charge (122) and this time she got her day in court when she testified that the arrests started after she had reduced her protection payments to him to just $1, which he indignantly refused, being used to $2 or more. (123) The judge convicted her anyway.

Also, a William Hanrahn (sic) was arrested on Morton Street for impersonating an officer (124) (a dodge used by small time confidence men to extort money from other criminals), and Marks Gruschenski, a notorious Morton and Dupont Street pimp, was arrested in the alley for battery on one Emile Robein, (125) who was likely another pimp.

That same year Terence Clark, a laborer who had lived at number 113 (126) since at least 1862, (127) leased his house to Leon Avignon for four years at the inflated rental of $100 a month, (128) making it apparent that Avignon was opening a brothel, since brothels and gambling clubs were the only businesses with large enough profit margins to afford rents like this. As some Morton Street property owners pointed out years later after the police finally closed down the brothels, they had done the only reasonable thing they could when the city failed to dislodge the prostitutes after the owners first complained: they moved out of Morton Street and leased their properties to the only people who still wanted them. (129)

However, the most interesting thing to happen on Morton Street in 1880, at least for future historians, was the U.S. Census, for this was the first census to include street addresses. When enumerators encountered a brothel, they seem to have treated it like any other habitation, and listed the inmates, including the madam, prostitutes, servants, and anyone else who lived there, occasionally even children. The addresses on the census sheets show that the houses occupied by Morton Street prostitutes that year (130) were the same ones labeled “Female Boarding” on the 1886 Sanborn maps, (131) confirming that by this time the brothels had replaced the residences on Morton Street. (132) The census also yielded additional data: the brothels contained 70 prostitutes and 10 madams, and about half the prostitutes were in houses run by madams while the rest were one-woman operations, with the latter mostly on upper Morton Street near Union Square. Almost half of the women were from other countries, mainly France. Though Asbury and Lewis said prostitutes of any race could be had on Morton Street, (133) the 1880 census listed 64 white prostitutes, with only one Hispanic and 5 black practitioners. There were no Asians or other races specified.

The 1880 census also showed that while some of the Morton Street prostitutes were younger women, the great majority were older than 25, many were in their thirties, and there were even a few in their forties. This was a marked change from the 1870 census (134) when most of them were between the ages of 18 and 24, suggesting a continuing deterioration in the class of prostitutes found there. Young women (or girls) who started out or reached their prime in parlor houses began to show signs of wear in a rather short time (numerous writers have documented how quickly prostitutes aged from the effects of disease, addiction, and ill-usage) (135) and moved, or were transferred, to other, cheaper houses again and again until they ended up in cribs (136) like the ones on Morton Street in 1880. This lent at least some support to Asbury’s statement that “the worst cribs in San Francisco were probably those which lined both sides of Morton Street,” (137) since they featured older and more used up prostitutes, at least during Morton Street’s middle years.

In contrast to this, the census sheets also show that Diamond Carrie Maclay’s brothel at 205 Post/108 Morton was probably operated as a parlor house, that is, a well-furnished brothel with young, attractive, expensively dressed women, even as the rest of Morton Street was in decline. She was open for business by 1880, (138) with 11 young women working for her that year. Her prostitutes were mostly in their late teens and early twenties and all were white with Anglo-Saxon names. The only two from outside the U.S. came from Canada and Ireland. As mentioned earlier, the houses were connected by a second-story passageway that spanned the back yards of both buildings and so were apparently operated as one unit.

What did Morton Street look like in the years that prostitution dominated its two blocks? Lewis didn’t describe it, while Asbury limited himself to saying brothels ran up and down both sides of the street. (139) But other writers – mostly newspaper reporters and editors and Harriet Lane Levy – did offer glimpses, (140) and the descriptions are of a piece: one story, two room cottages, each with a bay window, and each occupied by a prostitute who sat in the window waiting for customers. However, the Sanborn maps show them – with one exception (141) – to be two story houses built on 20 X 60 foot lots. Only two of the buildings had the bay windows reported by Harriet Lane Levy. The rest had flat fronts. (142) An 1892 newspaper drawing of a section of Morton Street shows a row of Carpenter Gothic frame houses with gabled roofs, icicle barge boards, wooden awnings with drips, small, decorative second-story balconies, and shuttered windows overlooking a board sidewalk. (143) Some 1896 newspaper drawings show several two story brick buildings. (144) Nor were they originally one story buildings with second story additions: newspaper real estate advertisements of the 1850s and 1860s (145) made clear that most of these structures were originally built as two-story single family houses.

The earliest reports of gambling found on Morton Street were in 1882 newspaper stories of raids on card clubs. These apparently started in August at number 15 in the back of the Geary House and at number 21 next door. (146) The card game at number 21, run by a Denny Haley, had 35 gamblers. (147) The one at number 15 was entered by way of the hotel’s back door and featured two faro games run by Wyatt Earp’s brothers, Virgil and Warren, of Tombstone fame. (148)

The raids were precipitated by a man named Charles Falk losing $2,800 at the Earps’ game, money he had embezzled from his socially prominent employers, the Bowie brothers. (149) The raid on the Earps’ game netted 15 gamblers, the faro layouts, and $1,422 in cash. (150) That the raids weren’t taken very seriously is perhaps shown by the Chronicle article’s opening line: “Last night occurred another one of those spasmodic raids which lately have been made on the gambling dens in this city.” (151) But it wasn’t just the newspaper being skeptical. Haley, the owner of the game at number 21, reopened the following night, necessitating a second police raid, just to show him they meant business – this time. (152)

In 1883 the March 11 Chronicle reported a raid on a faro game run by Ross and Carroll at number 21 that netted 19 gamblers, two faro layouts, and $1,171.75. (153) Another raid on the Earps’ game, still going at number 15, came up empty handed, the gamblers apparently having been tipped off. (154) The following month, the police raided numbers 15 and 21 again, but the gamblers managed to escape by the time the officers got inside. (155) In May the two games were raided yet another time and five men were arrested. (156)

The police raided another, though apparently much less expensive, faro game that operated above Patsy Hogan’s saloon at number 3, which netted three gamblers, the faro layout, and just $13 in dimes. (157) Hogan, whose real name was Patrick Keenan, (158) was a former boxer who plowed his winnings into operating a saloon called variously the Shades (159) or the Referee, (160) a hangout for pimps, prostitutes, swindlers, gamblers, and the other petit demimonde around Morton and Kearny Streets from 1882 through 1892. (His 1883 city directory listing reads “liquor saloon and gymnasium.”) (161)

Saloons had always operated on Morton Street, though usually at the corners, but the papers hadn’t reported problems with them until after the prostitutes took over the alley. Patsy Hogan’s saloon made the papers in January 1883 when a ne’er-do-well named McDonald was cheated out of $300 in a poker game there and was beaten up when he protested. (162) Edward Wild, a cowboy from Arizona who called himself Red Dick, (163) was taken to Hogan’s in December and robbed by two men. All three were arrested by the police when Wild threatened them with a six-shooter with a barrel over a foot long. (164)

The police raided the Ross and Earp games for the fourth time on August 30th. The Earps had enough time to hide the faro layout because the police found 15 men but no gambling equipment. However, the layout at Ross’ was confiscated after a lengthy search. (The papers reported that the dealer gave his name as “A. Stranger.”) (165)

This was also the first year that the old panel trick was reportedly used by the Morton Street women. (166) This was worked by a prostitute who put the customer’s belongings into a closet or cupboard or drawer for safe keeping while they transacted their business. In the meantime a confederate opened a hidden panel on the other side and removed the victim’s valuables, generally in the hope that he was too drunk to notice the loss until the prostitute had time to disappear.

By 1883 many residents and businessmen in the area around Morton Street had reached the limits of their endurance (167) and launched another attempt to shut down the brothels by submitting a petition to a Board of Supervisors’ committee asking them to order the city to move the prostitutes out of the neighborhood. (168) The committee referred the petition to Chief of Police Crowley who assured them that “such measures would be taken as will result in the abatement of the nuisance.” (169) The Board then adopted a resolution instructing the clerk to forward a copy of the current ordinances against prostitution to the Chief. (170) The police instituted a blockade of Morton Street that was effective enough to drive fifty of the women from the alley by the following week. (171)

While this was going on, the Police Commission was investigating one of its officers for accepting bribes from prostitute Margaret (or Maggie or Mollie) Kennedy at number 129. The evidence hinged on the testimony of two other officers who swore they saw him take a bribe from the woman while they were watching through a small hole in a door in the brothel. But when the Commissioners seemed to question the sworn testimony of the officers by asking to see the door and its hole to prove the allegation, the carpenter they sent to bring it to the hearing returned empty handed, saying he got the door but it was stolen while he was distracted. (172) However, the accused officer was dismissed from the force just days later. (173)

In the first three months of 1884, it began to look as though the Supervisors really meant what they said about shutting down Morton Street’s brothels. “The Morton-street blockade continues and many of the denizens (174) have been compelled to seek more congenial quarters,” wrote a reporter in the January 11th Chronicle. (175) Other encouraging signs of a Morton Street cleanup were seen in February when a man was found guilty of passing a dollar bill “raised” to look like a ten-dollar bill to a French prostitute on Morton Street (176) and was sentenced to five years at hard labor. (177) The next month a man who had robbed a customer at Patsy Hogan’s the year before was put on trial. (178) But there were still at least some brothels operating during this time because the police arrested another Morton Street prostitute for stealing $180 from a customer. (179)

But just days later an injunction restraining the Chief of Police from blockading Morton Street was requested by a Morton Street property owner who received a large income from the rents he collected from prostitutes, at least until the police blockade was instituted. He argued that since other brothel alleys weren’t being suppressed it was “against the law” to single out Morton Street and he also complained that the blockade was “proving injurious to the property.” (180) A temporary injunction must have been issued, for a little over six months later it was reported that it was finally lifted and the blockade reinstated. (181) By that time it was back to business as usual, as seen by the number of court cases involving Morton Street prostitutes and their maquereaux, (182) as well as several arrests of prostitutes for stealing from customers. (183) A frustrated Chief Crowley finally gave up (or, more likely, responded to a lessening of public pressure), (184) and lifted the Morton Street blockade in August 1885, saying it wasn’t working. (185) Ironically, the 1885 city directory listed the California Supreme Court as having moved into the newly rebuilt 221 Post Street, (186) above the O’Connor, Moffatt and Co. dry goods store, (187) where the court’s rear windows gazed magisterially down at the resumption of activity on Morton Street.

In 1886, the Sanborn Company published the first fire insurance maps of San Francisco. The maps showed the footprint of each structure on each city block and identified it according to its use, and this included brothels, which were coyly labeled “Female Boarding” or “F. B.” The maps for the two blocks of Morton Street show that every residential structure was so labeled, (188) confirming that the street had fallen completely into the hands of the prostitutes and their madams and pimps.

The maps also show that the effect of the transition from residential street to brothel alley was heightened by the arrangement of the buildings: instead of being randomly distributed among the alley’s commercial edifices, the residences were organized in blocks of houses. The largest group had thirteen adjacent structures covering almost the entire south side of upper Morton between Dupont and Stockton. Directly across the street were two more blocks of four and seven structures, the two groupings separated by a small coal yard but otherwise covering almost the entire north side of the street. And the fourth group had six structures on the south side of lower Morton near Dupont. In other words, there were 24 houses on upper Morton and six houses on lower Morton. (189) A conservative estimate of just two street level windows per house meant the unwary or otherwise disposed male passed 16 consecutive windows on lower Morton, each one with a woman inveigling him in one way or another, and 64 consecutive windows on upper Morton, with similarly behaving women in each one. Even if we rule out Asbury’s and Lewis’ lurid descriptions, the experience must have been memorable.

In 1887 the papers reported the same dreary tales of prostitutes arrested for stealing money from their customers. (190) But one of the most sensational stories was the finding of Henry Benhayon’s body in a room in the rear of the Geary House, the back of which faced lower Morton Street. Benhayon’s sister had been the third wife of J. Milton Bowers, a physician who killed her for her life insurance by administering phosphorous disguised as medicine. This caused the newspapers to dub her “the phosphorescent bride” because of rumors that her body glowed in the dark. Benhayon had been relentless in helping to convict Bowers and had been the chief witness against him. While Bowers was appealing his conviction, he had Benhayon killed by John Dimmig, a confederate. Dimmig rented a room in the rear of the Geary House and later brought Benhayon there through the back entrance on Morton Street and killed him by giving him liquor laced with poison. Dimmig tried to make it look like a suicide by leaving several empty poison bottles in the room, along with a forged letter purporting to have been written by Benhayon claiming that he himself had poisoned his sister. The death of the prosecution’s chief witness wrecked the case against Bowers, who was eventually acquitted and released. (191)

The next biggest Morton Street story was the December 1888 arrest of rookie police officer William S. Thompson for killing 23 year old Charles Rosenbrock when he tried to stop the officer from beating up a prostitute. Thompson and a veteran police officer had gotten drunk after a court appearance and wandered down Morton Street, still in their civilian clothes, where they insulted two of the prostitutes. The women responded in kind and were attacked by Thompson. (192) Rosenbrock, who was a pimp for a prostitute at 138 Morton, (193) happened to be passing by and tried to protect the women by knocking Thompson down, not knowing he was a police officer. Thompson then shot him. (194) Both officers were dismissed from the force (195) and Thompson was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to the maximum term of 10 years in prison, with the judge stating that he was sorry Thompson wasn’t convicted of murder so he could give him a longer sentence. (196) Also in 1888, a young man who suspected that his under-age sister’s boyfriend had placed her in a brothel followed them from their apartment. On the way, he enlisted the services of a beat cop and they watched them enter a Morton Street brothel, after which the officer took them to the city prison on Kearny Street and booked the boyfriend for pandering and the sister for admission to the Magdalen Asylum. (197)

By 1889 there were three saloons on lower Morton Street: Patsy Hogan’s at number 3, Charles Buise’ at numbers 5 and 7, and another one at number 39. There was a fourth in 1890 during a brief spurt of prosperity or competition that lasted just three years. One of them, the Strand, was operated by a well-known black pedestrian racer (a competitor in walking races, a popular 19th century sport) who bought it with his winnings. It did well for a while, until his generosity and mismanagement caused it to fail. (198)

Around that time there was this mysterious item in the Chronicle: “The large hat boxes which for some time past have stood on Morton street above Kearny, and afforded people a chance to make the vicinity obnoxious to those who were obliged to pass along Morton street” were removed by employees of the Superintendent of Streets to the city’s corporation yard. (199) Was placing hatboxes on the sidewalk in front of the brothels the prostitutes’ method of forcing passersby to walk next to their windows so they could lean out and snatch their hats? (200) There were also a number of arrests of brothel customers for robbing the prostitutes, (201) in addition to the usual arrests of the prostitutes for robbing their customers. (202)

The only newspaper mentions found of Asian prostitutes on Morton Street were several articles the following year. A police officer took a 12 or 13 year-old Japanese girl into custody who he found living in a Japanese brothel on Morton Street after he broke up a fight between the cook and one of the women. (203) A month later police arrested three Japanese prostitutes on Morton Street for “trying to entice men into their dens.” (204) The following year, police arrested another Japanese prostitute on Morton Street for keeping a nine year-old girl there. (205) This was also the last year that the California Supreme Court was listed on Post Street with its rear windows overlooking the brothels. (206) Had Morton Street become too much for the justices?

That same year, a 28 year old Fresno vineyard heir named Beauregard McMullin, who had been drinking heavily for two weeks, died by shooting himself in the mouth with a large bore pistol in Diamond Carrie Maclay’s brothel at number 108. He was jealously infatuated with Mattie Raymond, one of Maclay’s prostitutes, when one night he entered the brothel by the front entrance at 205 Post, went through the second story passageway across the backyard to Raymond’s room, and threatened to shoot her. She managed to escape, whereupon he turned the pistol on himself. (207)

A month later Diamond Carrie herself died in her brothel at age 36 from an opium overdose under circumstances that suggested a carefully planned suicide, (208) though the coroner ruled it was an accidental death. (209) Her estate was worth around $50,000 and she had made out her will only four months before. She left jewelry and clothing to some of her women friends, a number of small bequests to various relatives (her real name was Clara Cecelia Bedell), and most of the remainder to her mother, to be left to Maclay’s two sisters in the event of her mother’s death. The will, which was written in her own hand, went on to state that “the house at 205 Post street shall be conducted until the lease expires by Fannie Howard who shall receive for her services one-half of the profits; (210) the other half goes to the mother of the deceased.” She also left her library, two paintings, a silver tray and pitcher, and two silver goblets to her “dear friend” Judge Richard S. Mesick. (211) What made this last bequest so intriguing was the inscription of her initials on one of the goblets and his on the other. (212) Moreover, the executor named in the will was Mesick’s former law office clerk and later partner, Richard V. Dey, (213) who promptly asked the probate court to excuse him from this duty. (214) Meanwhile, he gave his approval for Maclay’s mother to apply to take his place. The mother then asked the court to appoint a law clerk named Edward W. Gunther (who worked for William F. Herrin, the chief counsel and political bagman for the Southern Pacific Railroad) in her place. (215)

Two months later Maclay’s father asked the court to appoint the Public Administrator as the executor in an apparent attempt to leverage a share of the estate – he hadn’t been mentioned in the will and was divorced from Maclay’s mother – alleging undue influence by one of Maclay’s sisters while Maclay was of unsound mind because of her opium addiction. (216) This was fought out over the next 12 months all the way to the California Supreme Court until the father finally settled for $2,250. (217) Meanwhile, the executor auctioned off the brothel to Sadie Young, (218) one of Maclay’s nearby competitors. (219)

Maclay’s 1893 estate appraisal listed 23 pieces of expensive diamond jewelry – hence her sobriquet. (220) There was also the $10,000 life insurance policy of her former inamorato, Judge Mesick, who signed it over to her in late 1887. (221) He now sued to get it back, but the insurance company said it was legally assigned to Maclay and they couldn’t renege on the reassignment. (222) When Mesick died later that year the newspapers published details about his life, (223) describing him as a high-living Virginia City lawyer (and later judge) during the Comstock silver rush. He charged high fees, worked hard for his clients, and lived expensively and generously, continuing this lifestyle after he moved to San Francisco. (224) The newspapers reported a number of bills from French restaurants and brothels, especially champagne bills, which surfaced after his death. (225)

Around this time, Gunther, who by now had replaced Dey as the executor of Maclay’s estate, (226) submitted his final accounting to the Probate Court (227) which revealed the estate paid over $11,000 for Maclay’s medical bills. (228) This fact, along with writing her own will just four months before her demise (229) at the young age of 36 (230) (and naming one of the prostitutes working for her to run the house after her death), (231) having a party with close friends the night before her death, (232) and then dying of an overdose from opiates in spite of being an experienced addict, all suggest that she killed herself to avoid the debilitating final stages of some chronic or fatal illness. (233)

During this period, the reform movements that swept across the United States into San Francisco in the last decade of the 19th century made the rising level of crime on Morton Street attract so much attention that the San Francisco Grand Jury included it in a recommendation made in November of 1891that the cribs and cow yards in the Barbary Coast, Chinatown, and the alleys running off of Kearny and Dupont Streets be either shut down or legalized and taxed to pay for the police, court, jail, and public health services so heavily used by the prostitutes, and to actively regulate them, as had been done in several other cities. (234)

However, indignation among reformers at the immorality of institutionalizing prostitution through taxation and regulation made certain this suggestion was never enacted. Instead, the Board of Supervisors responded the following month by passing an ordinance making it a criminal offense for Morton Street property owners and their agents to rent their premises for immoral purposes. (235) As a result, at least one property owner went to court to enjoin his tenants against conducting brothels in his building, (236) and at least one property manager was arrested for collecting rents from brothel owners. (237) But their charges were quickly dismissed by Judge Love (!), who advanced the novel argument that the new law violated the separation of powers by giving the Chief of Police the power to pass moral judgment on the tenants’ activities. (238)

More public pressure to suppress Morton Street prostitution emerged that year, when a diminutive and aggressive Salvation Army captain, a woman named Pauli of the C Corps (made up of 30 men and 8 or 9 women) invaded Morton Street and several other brothel alleys one night and did their best to disrupt business and call attention to their activities by singing and praying to the prostitutes and their customers. (239) Also, the members of a Grand Jury toured the Barbary Coast and the “tenderloin,” including Morton Street, (240) followed by police enforcement of an ordinance that required the prostitutes on Morton Street and other alleys to keep their window shutters closed. (241)

But things didn’t improve. In 1894 Marguerite Bormann, a prostitute at number 31, was slashed in the neck by a customer named Thomas Bowen who ran away while he was still half dressed. He was caught two blocks away at Post and Montgomery by a responding police officer when Bowen tripped over his still-loose clothing while trying to evade him. (242) Bormann died days later (243) and Bowen was convicted of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment at Folsom State Penitentiary. (244)

Also that year, a man named Ruddock, whose underage daughter ran away to live with an older man, found her in a Morton Street brothel where the man had placed her. She was returned home by the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children but ran away again with the same man. This time they got married before he returned her to the same brothel. Ruddock tracked them down again, had them both arrested, and pressed charges against the man. (245)

By this time the public was getting fed up with political corruption in San Francisco and a number of reform movements were strengthened and new ones started by growing public support, including initiatives to ban prostitution, much to the annoyance of the police. (246) These groups were able to parlay this growing dissatisfaction into the election of reform candidate Adolph Sutro as Mayor. Sutro took office in the beginning of 1895, (247) and two-and-a-half months later a Grand Jury returned eight indictments and a dozen presentments (statements of offenses observed by the jury) against the owners of properties on Morton and Quincy Streets who were renting their buildings to brothel operators. (248) This was followed by the arrests of several of the owners, (249) including at least two who had been among the early residents of Morton Street when it was still named St. Mark’s Place. In June, at the end of the Grand Jury’s six month term, the jurors submitted a report to the court pointing out that property owners were the direct beneficiaries of the huge rents being charged brothel owners, “and were the greatest obstacle in the way of regulating these women . . . these people, many of them of standing in the community, bring all the pressure and influence at their command to bear on the police authorities to exempt their places.” (250)

That year, the Supervisors responded to a request for regulation of the brothels, especially the ones on Morton Street, by concluding (perhaps hopefully) that what the public really objected to was the women sitting in full view at their open windows. They decided to consult with Chief Crowley about how best to put a stop to this. (251) Meanwhile, public pressure continued to grow when the Women’s Federation staged a large rally at the Metropolitan Temple at 5th and Jessie in which the featured speaker, a minister, said, “Let the respectable portion of San Francisco take a mighty stand against indecency. Let us stamp out Morton Alley and Dupont Street and every other damnable section of San Francisco.” (252) Yet another grand jury recommended that the brothels on Morton Street should be moved to some other location and that all public poker games should be closed. (253)

In 1896, it had been 26 years since the brothels had begun moving permanently onto Morton Street. But a series of events made this the prostitutes’ last winter there. It began with the Board of Supervisors asking the District Attorney for advice on how to close down the “social evil” on Morton Street. The Board was told that current laws were entirely adequate for this purpose – all that was needed was to enforce them. (254) Later that month the Civic Federation, one of several political reform groups, met and agreed to confer with reform-minded Mayor Sutro on starting a campaign to strengthen his executive powers. (255) The organization also commended the police for trying to close the Morton Street brothels. (256) The Federation of Women, a consortium of women’s clubs, also met and discussed the difficulties they faced in trying to close the Morton Street brothels, with a Mrs. French claiming “Some of these houses are owned by captains of police . . . others are owned by members of the Board of Supervisors, and others again by . . . pillars of the church.” (257)

The next month, a prostitute who called herself May Smith but whose real name was May McDermott, was strangled to death in her room at number 135 ½. (258) This was followed two weeks later by the apparent murder-suicide of May Conboy at number 108 ½. Conboy, the adopted daughter of a police sergeant, had moved away from home and become an alcoholic prostitute. She was reportedly shot by her boyfriend, who then shot himself. And while it was reported at first as a murder-suicide, evidence quickly emerged suggesting it was more likely a double suicide. (259)

The Smith/McDermott murder created a sensation in the press, but the death of Sergeant Conboy’s adopted daughter is what finally drove the brothels from Morton Street. The next day an order went out for beat officers to tell every Morton Street prostitute to pack her things and move or face arrest for vagrancy. (260) Reform groups immediately supported the order, and campaigned for the Board of Health to prosecute property owners renting buildings to brothel owners. (261) The Grand Jury and the Chief of Police were “assured by leading merchants, property owners and representative men generally that arbitrary and extreme measures under the law to abolish [the Morton Street brothels] will be fully sustained by public sentiment.” (262)

Many of the women moved elsewhere, (263) though seven of them filed damage suits against the police on February 28th and requested an injunction prohibiting the police from blockading their brothels. (264) Not surprisingly, the court dismissed the request. (265)The next day the Police Commission announced that the remaining Morton Street prostitutes had to vacate their premises by March 4th or they would be arrested, (266) and by that date they were all gone, (267) while police officers were kept stationed on Morton Street to make sure the prostitutes didn’t return. (268) The police had finally proven what most people in San Francisco already knew, that they could have closed the brothels any time they wanted, but hadn’t done so until now, mostly for reasons of policy. (269)

The following month real estate transactions involving Morton Street properties began to appear in the newspapers as property owners, no longer getting any income from their buildings, offered them for sale or transferred them to relatives. (270) Businessmen began to make plans to build commercial structures on the street, (271) and a Hobart estate project was completed in December. (272)

There were a handful of attempts to reopen Morton Street to prostitution over the next several years. In July 1896 the grand jury learned that some Morton Street property owners were circulating a petition signed by many nearby Kearny and Grant Avenue businesses that depended on the Morton Street brothels to attract customers to the area. (273) The petition asked that the police blockade be lifted and that they be allowed to reopen their properties as “lodging houses.” (274) It was presented to the Board of Supervisors in September where it was referred it to the Health and Police Committee. (275) John Baumann, one of the early St. Mark’s Place residents who had been driven out by the prostitutes after 1875, told the Committee that the street closure was a scheme by a grand jury member named O’Farrell to drive Morton Street real estate prices down so he could buy them cheaply. (276) Baumann also claimed that no respectable tenants would rent their properties at any price as long as the police kept the street under surveillance. The committee ducked the issue by placing the petition on file and referring the protesting property owners to the Chief of Police. (277)

But events conspired to keep the brothels closed. In November 1896 it was learned that a petty thief had broken into the empty houses along Morton Street, torn up the carpets, and sold them, (278) making the houses less habitable and more expensive to renovate. In January 1897 the Chronicle reported that the lots at numbers 122 and 124, recently purchased by Vittorio Menesini, (279) would be used to extend his Post Street business building all the way back to Morton Street, (280) thereby eliminating one of the old buildings and its cribs. In March of that year the abandoned brothels at number 129 and 131 were damaged from a fire in a nearby cape factory on Geary Street, rendering them uninhabitable. (281) In May the houses at numbers 110 and 112, both former brothels, were sold to real estate developer Isabella Levy who planned to redevelop the properties. (282) And in April the grand jury managed to shut down the straw bail operation (283) of James Keating, one of the owners of the Hub, (284) Morton Street’s last remaining saloon, (285) thus scoring a less direct, but still significant blow against Morton Street prostitution.

In July 1897, the Health and Police Committee of the Board of Supervisors blocked another apparent attempt to bring back the prostitutes when they refused a second request by owners of the Morton Street properties to remove the police blockade. (286) That month a lawyer representing the property owners along lower Morton Street asked the Supervisors to substantially reduce their property tax assessments because their buildings weren’t generating any revenue since the closing of the brothels. The Call noted dryly that “the matter was taken under advisement.” (287)

In August the Chief of Police learned of a plan to rent out the remaining Morton Street buildings as saloons and for “other business purposes” to accommodate prostitutes who were being chased out of Dupont Street. (288) The Board of Health headed this off by inspecting the structures and condemning them in November as unfit for human habitation, while also citing the owners to either repair or remove them, or the city would tear them down and bill the owners for the cost of demolition. (289)

However, there were still occasional troubles, for in September 1897 two men were arrested in The Hub saloon at the corner of Grant and Morton when one took out his pistol and shot at the other, who was throwing cobblestones at him. (290) Two days later a man stabbed another man outside the Hub over an argument about the merits of various boxers. (291) A noted former prizefighter, a black man named Bill Price, was taken to the county hospital in November after he was found lying on the floor of one of the abandoned brothels, starving to death after he lost his job as a one-eyed bouncer at a Barbary Coast saloon. (292) Meanwhile, legitimate businesses stayed away for the first three years following the closing of the brothels. (293)

In March of 1898, James Keating still owned the Hub saloon, Morton Street’s last remaining dive. He and his wife Mabel, an opium addict who the press called “the queen of the pickpockets,” were shot by Jerry Sullivan, a City Hall janitor, while inside the Hub. (294) Sullivan, who was also an addict, did this after accusing Keating of being a police informant. He said later, “I admit I shot the guys, and I’m sorry I didn’t kill them.” (295) Later reports stated that Mrs. Keating, a woman of many aliases, actually made her living robbing inebriated slummers, and the shooting had been the result of a lover’s triangle involving the three of them. The Hub closed soon after the shooting. (296)

Meanwhile, a new Grand Jury found that closing down the brothels on Morton and Glasgow Streets, as well as on St. Mary’s Place, was perhaps too much of a good thing: the displaced prostitutes, no longer contained in their downtown locales, had scattered and were operating in the city’s residential neighborhoods. The Grand Jury quickly recommended “that ‘no more of these alleys be closed.’ ” (297)

But in spite of the apparent cold feet of the business community, in 1898 developer Sanford Sachs accumulated a block of several properties (numbers 115 through 119) for a building project. (298) Around the same time, property owner Vittorio Menesini began construction of a six story extension to his Post Street building on the site of one of the old brothels. (299) The Chronicle reported Isabella Levy, another real estate investor, had assembled a 45 foot frontage along the south side of upper Morton Street between Grant and Stockton next to Sachs’ block which they both planned to develop into business buildings. (300) And Moses A. Gunst moved the main location of his cigar store chain to the storefront on the northwest corner of Kearny and Morton Street. (301)

Levy, Sachs, and other Morton Street property owners, as well as “a large number of business men in the vicinity” petitioned the Board of Supervisors to change the street’s name from Morton Street to Union Square Avenue, in honor of the nearby park, to rid the alley of the associations of its former name. They complained that the houses along the alley were vacant for the previous twenty-eight months and that “The property in consequence has so depreciated in value that several sales have been made at less than the assessed value.” In addition, the banks refused to loan any money on the land since no rents were being collected. Moreover, no one would rent the properties because of the street’s reputation as a former brothel alley. (302) The Board complied with this request a month later. (303) One newspaper article also noted that Sachs’ and Levy’s acquisitions represented a trend: small property owners were selling out to developers along these two blocks. (304) That same month the first block of the newly renamed street was one of many thoroughfares included in an order by the Board of Supervisors to replace the old cobblestones with asphalt paving. (305) And a proposal was unveiled by a local businessman to remodel Union Square Avenue (which was still being called Morton Street by the press) into a covered arcade like those in European cities. (306)

Meanwhile, a sort of ex post facto object lesson on the wages of Morton Street sin was reported in several articles by the Chronicle. Walter Ross, who had been sent to Folsom Prison for assaulting and robbing his mistress, a Morton Street prostitute named Grace Walls, was stabbed to death in a prison dining room brawl in 1898. (307) That same year Patsy Hogan, the former owner of the Referee saloon on Morton Street, shot and killed his estranged wife and attempted to shoot and stab himself. He was later acquitted by a male jury that sympathized with his story of temporary insanity and self-defense. (308) In 1900, Matthew Collins, the police officer who was dismissed after he was accused of accepting bribes through a hole in a door in a Morton Street brothel and was now a special officer in the produce district, was arrested for pistol whipping a businessman when he was drunk while on duty. (309) Around that time, the police found and arrested the likely killer of May McDermott, (310) only to see the courts release him on a straw bail bond accepted by a corrupt court clerk. (311)

In 1899, legitimate businesses finally began moving onto Union Square Avenue. These were the Elite saloon at number 8 and “KOCH THE PAINTER” at number 23. (312) In July the Chronicle reported that the Francis-Valentine Co., at that time the oldest printing business in San Francisco, (313) had moved to numbers 103 through 109, (314) where the brothels nearest Grant Avenue used to be housed. (315) A Central California banker saw an investment opportunity in the cleaning up of Morton Street and bought two lots in September on which to build a manufacturing concern. (316) Real estate developer Anna Whittell started construction of the three-story Whittell Building at numbers 33 through 35½ after razing one of the old brothel structures. (317) Work began on a five story structure at another former brothel site at number 110. (318) It was announced in December that the old Sherman House lodgings at the southwest corner of Grant and Morton, the site of one of the old basement concert saloons, was to be torn down and a four story business building erected to take its place. (319)

Two more legitimate businesses moved to Union Square Avenue in 1900, (320) a wholesale florist in number 23, and a builder in number 133. A. Aronson bought two other former brothel sites at numbers 118 and 120, and secured a permit to build a six story warehouse on the site. (321) The press, while still not warming up to the new street name, did start referring to it as “formerly Morton Street.” (322) And, though the Olympic Gun Club moved out of its rooms on the northwest corner of Kearny and Union Square, (323) the toney Monticello Club moved in a week or two later. (324)