From Post to Park

Historical Essay

by Pete Holloran

The D-Streetcar at the Presidio terminus, Golden Gate Bridge in background, Sept. 11, 1935.

Photo: SFMTA Photo Archive

In October 1994, the U.S. Army vacated the Presidio of San Francisco, bringing to an end nearly 150 years of continuous military occupation--the longest tenure of any Army garrison in the American west. After two centuries of military service (it was established by Spanish soldiers in 1776), the Presidio may become a model for military base conversion. It could just as easily become yet another victory, however, for monied interests and unsustainable development.

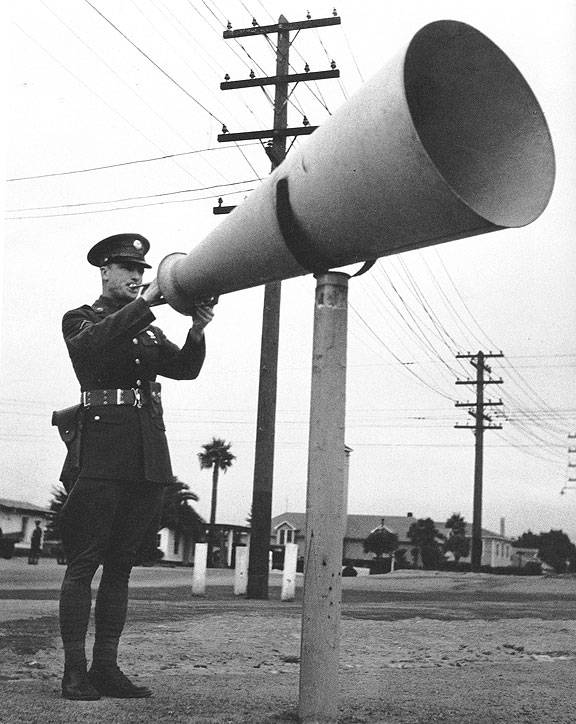

Soldier plays reveille into early amplification system, c. 1934;

Photo: Shaping San Francisco

The Presidio is now part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area (GGNRA), which features well-known landmarks such as Alcatraz and Muir Woods among its 76,500 acres, making it one of the largest urban national parks in the world. Twenty million people visit GGNRA lands every year; 3.5 million visit the Presidio, with more than 8 million expected within fifteen years. Millions of dollars of planning and years of community meetings produced a general management plan that sought to make the Presidio "a working laboratory to create models of environmental sustainability that can be transferred to communities worldwide" (GGNRA, 1994). Finalized before the November 1994 elections, the plan has now been dramatically altered by congressional Republicans. Balking at the $25 million annual cost--more than the annual budgets of Yosemite and Yellowstone combined, but far less than the Army spent to maintain a skeletal presence--congressional Republicans seek to make the Presidio pay for itself within fifteen years or be turned over to the General Services Administration for sale.

The unusual history of the Presidio makes it unlike most other parks in that its 1,480 acres (ca. 600 ha) contains more than 800 buildings and other associated urban features including a bowling alley, a fast food franchise, and a golf course. Some substandard buildings will be demolished, but 510 are considered historic as a result of its designation as a National Historic Landmark. Historic structures will be rehabilitated and, according to the plan, will house "a network of national and international organizations devoted to improving human and natural environments." A federally chartered partnership institution was proposed to assist the park service in building rehabilitation and leasing. Known as the Presidio Trust, this institution would seek an estimated $600 million in loans from the U.S. Treasury over the next fifteen years to finance rehabilitation. As amended by House Republicans, however, the Presidio Trust legislation subverts the management plan's environmental vision by making profitability the primary consideration in leasing and rehabilitation. The compromise legislation is grudgingly supported by most longtime participants in the Presidio planning process, including the Sierra Club, local congressional Democrats, and the National Park Service, although the amended legislation requires NPS to transfer control of most Presidio operations to the Trust.

Governed by a five-member board chosen primarily on the basis of real estate and leasing expertise, the Trust does not inspire confidence among those concerned about the Presidio's open space. Established primarily to make the post's buildings profitable, the Trust does not have a clear mandate to conserve the Presidio's natural values. As one of the last places sheltering remnants of a distinct Franciscan biogeographic province, the Presidio and its natural areas are not just window dressings that make buildings more attractive to potential lessees, but an important regional and national asset worthy of conservation and restoration.

Of the 800 acres of open space (54% of total area), approximately 145 acres support remnant native plant communities that provide habitat for twelve rare or endangered plant species, including three federally-listed species and one proposed for listing. The last wild individual of the Presidio manzanita (Arctostaphylos hookeri ssp. ravenii) was first located by Peter H. Raven in the late 1940s and is still thriving nearly fifty years later. In 1949 Raven discovered another endemic species, the Presidio Clarkia (Clarkia franciscana), while documenting San Francisco's vanishing flora as a teenager. The Presidio also provides refuge for five of the last six populations of another San Francisco endemic, the San Francisco lessingia (Lessingia germanorum).

These plant communities are threatened by all four of what Jared Diamond identified as the main mechanisms of human-caused extinctions: effects of introduced species, habitat destruction, overcollecting, and "secondary ripple effects" (Diamond 1989). Urban development of the San Francisco peninsula has fragmented natural communities into tiny remnants distinguished by a depauperate fauna that includes only the most adaptable species. Characterized by a high perimeter-to-core ratio (if a core can be said to exist at all), natural areas are readily colonized by legions of invasive non-native plant species, including many still popular among urban gardeners and landscapers.

The history of serpentine grasslands and serpentine maritime chaparral illustrates the forces responsible for the decline of San Francisco natural areas. Serpentine outcrops--composed of serpentinite, California's state mineral--were once fairly common in San Francisco, stretching in a discontinuous patchy band across the peninsula from the southeast corner to the Presidio in the northwest. Green-tinted serpentine outcrops appear occasionally among the city's buildings, but only at the Presidio do they still support native vegetation.

El Polin Spring, Sept. 2008, Presidio

Photo: Chris Carlsson

These native plant communities escaped development, but not unscathed. Mediterranean annual grasses have come to dominate most California grasslands, but chemical properties of serpentine soils have enabled serpentine grasslands to resist complete conversion to annual grasslands. Serpentinite weathers into a thin rocky soil containing high levels of heavy metals such as magnesium, nickel, and chromium that in high enough concentrations can be toxic to plants. Serpentine soil is also characterized by low levels of calcium, nitrogen, and other essential elements. Plants growing in such low-nutrient soils are often dwarfed in size and stature, and sparse plant cover in turn alters physical conditions--increasing surface temperatures, for example--that further restrict plant growth. Ten percent of California's endemic flora are restricted to serpentine soils, even though such soils cover only one percent of California. Other native plants that were once found on a variety of soil types are now largely restricted to remnant serpentine grasslands.

The small size and patchy distribution of serpentine plant communities have contributed to the decline, endangerment, and extinction of serpentine-dependent species. Naturally-occurring local extinctions become permanent once reserves, particularly in urban areas, become surrounded by inhospitable habitat. These areas would once have been recolonized from nearby refugia, but are now effectively sealed off from similar plant communities. The Bay checkerspot butterfly (Euphydryas editha bayensis) was once relatively common in San Francisco, but is now found only in larger reserves south of the city (Hafernik & Reinhard 1995).

Disturbance associated with high human use can also have dramatic effects on serpentine plant communities. Proliferation of informal trails caused the Presidio's largest population of the threatened Marin dwarf flax (Hesperolinon congestum) to plummet from several thousand to less than a half-dozen in just a few years. (Its habitat has now been fenced off to allow recovery.) Domestic pets cause additional disturbance by digging after gophers and depositing nitrogen-rich feces. Adding nitrogen to serpentine soils allows non-native annual grasses to invade (Huenneke et al. 1990?). Other sources of nitrogen include nitrogen-fixing non-natives such as french broom (Genista monspessulana) and even smog.

The Presidio's small and extremely isolated serpentine plant communities will never again provide habitat for several extinct species, including the Franciscan manzanita (Arctostaphylos hookeri ssp. franciscana), a close relative of the nearly-extinct Presidio or Raven's manzanita (Arctostaphylos hookeri ssp. ravenii). Several have become quite limited in range and population size, including the San Francisco owl's clover (Triphysaria floribunda), an annual hemiparasite that was not seen for several years before nine individuals were located in 1995--right next to the last wild Raven's manzanita.

--Pete Holloran

[adapted from Pete Holloran, "The Greening of the Golden Gate: Community-based Restoration at the Presidio of San Francisco," Restoration & Management Notes 14, no. 2 (1996)]