California Midwinter Fair of 1894: An Orientalist Exposition

Historical Essay

by Barbara Berglund

View northeasterly from Strawberry Hill over grounds of the 1894 Midwinter Fair in Golden Gate Park.

Photo: Private collector, via OpenSFHistory.org, wnp15.081

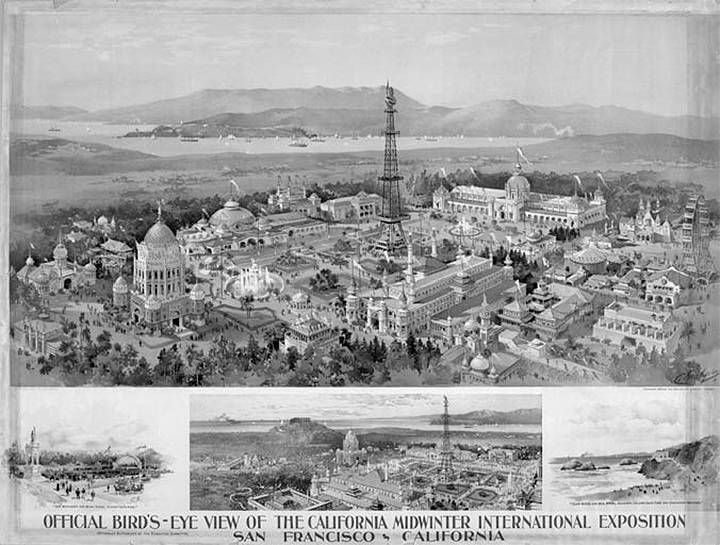

1894 California Midwinter International Exposition, the first held west of Chicago.

Image: Bancroft Library

The California Midwinter International Exposition—also known as the Midwinter Fair—was held in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park from January 27 to July 4, 1894. Following on the heels of the World’s Columbian Exposition, it showcased selected exhibits from Chicago’s spectacular commemoration of the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s journey to America as well as an impressive number of new exhibits at its specially constructed fairground, Sunset City. The driving force behind this extravaganza was Michael H. de Young, the publisher of the San Francisco Chronicle, who had also been Commissioner of California Exhibits at the Chicago Fair. In Chicago, he determined that San Francisco could reap economic and social benefits from hosting a similar fair. The city, like the rest of the nation, was reeling from the effects of the economic depression of 1893.(1)1

De Young envisioned staging a publicly funded venture that would reinvigorate the local economy and advertise San Francisco by showcasing California’s temperate winter climate and agricultural bounty to visitors and potential migrants alike. He called a meeting of the local businessmen with him in Chicago, pitched his idea, and despite some skepticism, he extracted pledges totaling over $40,000—enough to get the enterprise off the ground. Although it had taken seven years to bring the Columbian Exposition to fruition, in eight busy months fair organizers set up a corporate-style administrative structure and ran successful local fund-raising and publicity campaigns. They arranged for many of the exhibits from the Chicago Fair to be carried by rail to San Francisco, developed an impressive number of new exhibits, and designed and built Sunset City. While the rush to completion was evident in areas where landscaping was sparse as well as in the delayed opening of some exhibits, the Midwinter Fair was nevertheless even more of an economic success than its promoters had hoped. By the time the fair closed on July 4, 1894, nearly two-and-a-half million people had attended.(2)

As the first American international exposition ever held west of Chicago, the Midwinter Fair provided San Francisco elites with an opportunity to present an image of the city to local, national, and international audiences. While the Mechanics’ Institute fairs were small and local, their long history as a ritual cultural frontier offered important lessons in how to coordinate an event like the Midwinter Fair and use it to convey an ordered vision. The leaders in business, finance, and industry who joined de Young in organizing the fair pursued their course with the blessings of the mayor, the governor, and other state and local officials. Although central, northern, and southern Californians all had their representatives on fair committees, the Midwinter Fair’s leading organizers were drawn from San Francisco’s political, economic, and intellectual elite. These men sat at the helm of a city that, although less than fifty years removed from conquest had become, by 1890, the largest city on the West Coast and the eighth largest in the country. In planning and designing Sunset City, they created a paean to America’s landed empire that showcased San Francisco—the jewel in the crown of western expansion and a burgeoning yet still relatively new American place that had its roots in the formative crucible of the frontier. With the frontier having been deemed officially closed by the Census Bureau in 1890, many of the fair organizers believed it was time for San Francisco to shake off some of its boomtown reputation. As banker and civic leader James D. Phelan announced at the Midwinter Fair’s inaugural ceremonies, “We celebrate to-day this great fact—a history-making fact in the annals of the world—that the American people have reached the Pacific Ocean, and that civilization, having sprung in the remote east and pursued its destined course, has reached the western edge of the American continent in California . . . ‘The eastern nations sink, their glory ends, / An empire rises where the sun descends.’”(3)

The Arts area of the Midwinter Fair, later to become the Concourse amidst the DeYoung Museum and Academy of Sciences.

Photo: Private collector, via OpenSFHistory.org, wnp15.123

The fair’s displays that exhibited local progress in manufacturing, agriculture, industry, and technology captured one component of what the arrival of civilization meant in California. But another part of what civilization’s presence on the continent’s edge signified were the ways California, and especially San Francisco, had gone from the social disorder of the gold rush years to a society organized along lines that were much more in keeping with national norms. Through this process, this frontier region became recognizable as part of the nation. Through the fair, elites fashioned a story about the city as a distinctive place—with its own history and vision for the future—but placed squarely within the contours of the national story and central to the nation’s development. On this level, the Midwinter Fair—as the elaborate fantasy of an anxious yet powerful elite—served as a cultural frontier that embodied the kind of ordering hierarchies that this elite had imagined, and had to some degree realized, for the city itself. Despite the fact of continual, stubborn social disorder, San Francisco in 1894 was not the socially fluid place that it had been in 1849. And, at the fair, just as in the city itself, the elite’s ordered vision was at times successful, and at other times disrupted and undermined by people and forces beyond its control. Four aspects of the Midwinter Fair shed particular light on the connections between the social hierarchies this extravaganza represented and the vision of social order it promoted: the symbolic significance of its Orientalist architecture, the version of history articulated in its ’49 Mining Camp exhibit, the gender politics of women at the fair as workers and as spectacle in the context of commercialized leisure, and the economic tensions disclosed at an event promoted as a balm for healing class divisions. A central purpose of nineteenth-century expositions was to demonstrate the technological achievements and social hierarchies that constituted civilization. Although Chicago and San Francisco—and the eleven other international expositions held between 1876 and 1916—shared a vision of order and progress grounded in white racial dominance, patriarchal gender relations, and industrial class relations, they each chose different styles of architecture and design that fit with local and regional conditions. During the planning stages, San Francisco’s Executive Committee operated under the assumption “that there was time enough, and artistic energy enough, for the development of a marked individuality” in the Midwinter Fair’s architecture. Its members hoped that the buildings would capture “something of the characteristics of the locality and the people in whose midst the Exposition was to be built.” De Young, as the fair’s Director-General, had suggested that one way to avoid “the architectural reminiscences of Chicago” would be to “make their studies from the Japanese, Chinese, Indian, Egyptian, Moorish, and old Mission buildings.” When the local architects who competed to design the buildings submitted their creations, it was found that de Young’s suggestions “had been kindly received and largely acted upon.” The architecture of the Chicago Fair was neoclassical; in San Francisco, it was broadly Orientalist.(4)

Close-up on the Fine Arts Building that later became the DeYoung Museum.

Photo: Private collector, via OpenSFHistory.org, wnp15.096

The Midwinter Fair’s Orientalist theme was given its most spectacular expression in the five main buildings that formed Sunset City’s Grand Court of Honor: Manufactures and Liberal Arts, Mechanical Arts, Horticulture and Agriculture, Fine Arts, and Administration. Each of the Grand Court’s buildings combined a variety of Oriental styles and each possessed “an interesting individuality” and “unconventionality.” As a whole, this turn toward the Orient presented a marked departure from the emphasis placed on balance, order, and architectural uniformity in Chicago’s White City’s expression of a hierarchically organized society in its imposing, symmetrical facades. A. Page Brown, the chief architect of the Midwinter Fair, designed the Administration Building using an eclectic mix that included both Moorish and East Indian influences. He was also the architect for the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building, which had “something of the old Mission character in its architecture, with Moorish detail” and featured a much-noted turquoise blue dome and golden cupola. The Horticultural and Agricultural Building, the work of Samuel Newsom, was “distinctively characteristic of the early Spanish period in California.” C. C. McDougall’s Fine Arts Building was described as Egyptian and “covered with hieroglyphs” with “a suggestion of the temples of India in the pyramidal roof.” The Mechanical Arts Building, the creation of Edmund R. Swain, was “East Indian in appearance” and was said to bring to mind “the Jumma Musjid at Delhi” and “the Pearl Mosque at Agra.” Finally, the buildings of Sunset City were not white but painted colors chosen to evoke a sunset over the Pacific. Pink, turquoise, gold, vermilion, and greenish gray accents enlivened their creamy ivory facades.(5)

The Manufactures Building. The Midwinter Fair’s architecture was broadly Orientalist. This building, one of the five that constituted Sunset City’s grand court of honor, was designed by A. Page Brown to convey both Mission and Moorish influences.

Photo: I. W. Taber, photographer. Souvenir of the California Midwinter International Exposition 1894, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

The literature of promoters and boosters—taken at face value—offers one way of reading the symbolic significance of Sunset City’s Orientalist architecture. According to The Official History, “the marvelous city of towers, minarets, domes and castles” reflected “the spirit of California.” This was defined as encompassing “the individuality of Californians” as well as their “dash and daring.” This spirit likewise included “the freedom, the liberality, the open-handed hospitality, which are proverbially Californian characteristics.” It also embodied “the strangely beautiful blending of the East and the West.” Taken together, Sunset City exemplified “the most complete expression of a new civilization.”(6)

But just below the surface, there were other less sanguine meanings suggested by the Midwinter Fair’s Orientalist architecture. Although this particular style did not express the mastery of order and balance implied by neoclassicism, it nevertheless symbolized an ordered vision. By choosing Orientalist architecture, Sunset City’s planners actively looked to the imaginings of a powerful, imperial Europe to symbolize the new civilization of the United States in the Pacific West. Sunset City’s embrace of Orientalist styles was undergirded by an understanding of the Orient—known as Orientalism— that developed as Europe extended its imperial control over parts of Asia, India, and North Africa. Through the selective appropriation of cultural artifacts as well as styles of architecture and design, Europeans produced what came to be recognized as the authoritative representation of the Orient. In this representation, which was based upon a sense of ownership, Europe constructed “the Orient” as inferior to the “Occident.” In doing so, Europe strengthened its own identity and reaffirmed its dominance over colonized peoples and places. Sunset City’s Orientalism, although founded upon European precedent, was both more broadly and somewhat differently conceptualized as a result of local conditions. In addition to encompassing East Indian, Egyptian, and Moorish qualities, it also claimed the power to represent Chinese, Japanese, and the related Mission and Spanish Colonial styles.(7)

The Columbian Exposition’s White City had offered Americans a utopian vision of a well-ordered city. It emphasized the consolidation of the country’s landed empire and displayed the United States as a country ready to dominate the other nations of the world. If some of the first ideological steps toward realizing the nation’s nascent overseas imperial ambitions were taken at Chicago, the second steps were taken at the San Francisco fair. The Orientalist architecture of Sunset City represented San Francisco as “The Imperial City of the West” and communicated a more aggressive and targeted imperial position. Sunset City declared the United States—by way of San Francisco, its far Western commercial, financial, and military outpost—a force actively reaching out toward and desiring dominance over Asia and Latin America. In this sense, Sunset City looked outward, to order places and people beyond the city. “It is through this ocean gateway,” Taliesin Evans’s popular guide to the fair reminded its readers, “that the commerce of the nation with the Orient, with the lands of the Pacific, with Australasia, the Russian and Asiatic Possessions, British Columbia, the western coasts of South and Central America and the bulk of the commerce of Mexico passes.” Just four years later in 1898, the United States annexed Hawaii while troops en route to the Spanish American War—which resulted in further overseas imperial acquisitions—were stationed at San Francisco’s Presidio precisely because of its strategic location as a base for American expansion into the Pacific.(8)

In extending and adapting Orientalism’s formulation, Sunset City wove together a web of outward facing positions that expressed the kinds of relationships that the United States in the Pacific West desired with those beyond its borders and inward looking stances that reaffirmed local power relations. Sunset City’s use of Orientalist architecture represented deep desires and anxieties connected to the local conditions and imperial ambitions of San Francisco and California vis-à-vis the American West, the American nation, and the Western Hemisphere. For example, following the logic of European Orientalism, the fair’s promotional literature’s renditions of Mission and Spanish Colonial styles created a “mythical architectural past” that echoed an equally mythical social history. The fair’s Official Guide blithely suggested to readers that “whatever this Spanish period may have been to the people who actually lived in it, to modern Californians it is a heritage of legend and romance.” Accordingly, the period was represented as one of “old grey Mission churches, with their tiled roofs, pillared corridors and high altars, crumbling into rust and dust;” “low, weather stained ranch houses where the haughty Dons lorded it in feudal fashion, and where the sound of the guitar and the castanets still seem to linger;” and “ruined presidios where swash-buckler soldiers passed their days in rough, careless gaiety.” Remnants of this not-so-distant past could be seen “in many a suggestive bit of architecture or display of costume, custom or handiwork within the walls of the Midwinter Exposition.” Through these kinds of representations of Mission and Colonial styles—that existed more in the imagination of Americans than they ever had in the reality of Mexican California—the Midwinter Fair, echoing mainstream histories of the region, presented conquest as an act of generosity, in which civilized Anglos lifted the lazy, yet romantic and colorful Californios out of the semi-barbaric state in which they had languished. This representation spoke to the position of Mexicans and Californios within the state’s borders as dispossessed colonized peoples and manifested a powerful image of Latin American nations as decaying and primitive that worked to justify and encourage the United States’ increasingly imperial and bellicose posture.(9)

The inward and outward looking ordering visions of the Orientalist architecture manifested in the quadrangle of buildings that formed Sunset City’s Grand Court were reinforced by a number of concessional structures and exhibits that existed beyond the court’s boundaries.(10) As the Official History explained, the fair’s overall “arrangement assumed something of the character of an inner circle of purely expositional buildings with an outer concentric circle of concessional features.”(11) It was along this outer ring that a visitor to the fair would find, among other things, the Chinese, Japanese, Hawaiian, and Esquimaux exhibits. According to the Official Souvenir, the purpose of the various buildings and village settings that made up these displays was purely educational. “The villages of Hawaii, Esquimaux, China, Japan and other localities are perfect reproductions of the originals in the lands they represent, and the whole is an object lesson which no book could teach. . . . a living and moving encyclopaedia.” In a sense, this was true, as the reality these exhibits represented did have a pedagogical mission. More often than not, displays of Asians, Native Americans, and Pacific Islanders used Orientalist logic to instruct observers in the racial difference, strangeness, and barbarism of the exhibited groups. Although some of these exhibits had appeared at the Columbian Exposition, in San Francisco they were arrayed against a different local context. The social meanings derived from the exhibition of these peoples and cultures arose from the confluence of San Francisco’s relatively high percentage of residents of Asian descent; its equally long history of anti-Asian racism; the conquest of the region’s Native American inhabitants; and the nation’s most recent imperial ambitions that necessitated the evaluation of the inhabitants of the Pacific as potential colonial subjects.(12)

The Chinese and Japanese exhibits created representations of these countries that had relevance for how China and Japan as distant nations were imagined as well as for the ways Chinese and Japanese residents in California were perceived. The Chinese Building, designed by a local architectural firm and financed by the city’s Chinese merchants, allowed visitors to view and possibly purchase “the deft handiwork of Chinese artisans and the wonderful products of Chinese ingenuity” and provided “a curious and instructive object-lesson of the architectural ability of the inhabitants of the great Empire of the East.” But the positive associations that could be derived from the Chinese Building about the achievements of Chinese culture were tempered by negative associations with Chinatown. Since the Chinese Building contained a restaurant, tea house, joss house, theater, and bazaar it not only replicated many of the standard sites of Chinatown’s tourist terrain but also the racializing work done by them.(13) The fair’s promotional literature even told visitors that all of the “attractive features” of Chinatown could be seen at the exposition’s Chinese Village “under much pleasanter conditions”—thus playing on prevailing stereotypes of the neighborhood as filthy, malodorous, and teeming and conjuring up unfavorable images of Chinese immigrants willing to live in such an environment.(14)

Visitors to the fair’s elaborate Japanese Tea Garden were told by Taliesin Evans’s guidebook that with “one step” they would pass from “the grand plaza of this great achievement of Western civilization into a romantic scene faithfully depicting life in the ancient, but still semi-barbaric, ‘Land of the Mikado.’” Conceptualized and designed by ardent Orientalist and local purveyor of Japanese goods George Turner Marsh and built by Japanese craftsmen, the Midwinter Fair’s Tea Garden featured an impressive gateway, a thatch and wood tea room, and a three-story theater that hosted the performances of a troupe of Japanese jugglers. Japanese landscapers filled the grounds around the Tea Garden with various plants and bonsai trees, tranquil ponds, bridges, winding paths, restful benches, and colorful lanterns. Although Evans had initially described Japanese culture as “semi-barbaric,” he also noted that the Japanese exhibit illustrated “the great regard of the Japanese people for cleanliness and fresh air in their homes, and public places, and their instinctive love for art and fine workmanship.” The Monarch Souvenir of Sunset City and Sunset Scenes took a less charitable view and emphasized the religious and racial differences of the Japanese that could be inferred from the exhibit. It explained to readers that the “peculiar style of Japanese architecture” was “suggestive of all sorts of mysteries, to say nothing of idols and heathen rites” that were “a part and parcel of the home life of the ‘little brown men.’” Here, even when the grandeur of a distant Asian civilization was invoked, it was double-edged and coupled with demeaning statements designed to highlight the inferior and less than fully civilized status of the Japanese and their culture vis-à-vis the West.(15)

The Midwinter Fair’s exhibitions of Hawaiians and Inuits took place against a backdrop of heightened anxieties about the suitability of these colonized peoples for integration into the American nation. The San Francisco Morning Call described the Midwinter Fair’s Hawaiian Village as displaying “a street of ancient Hawaiian straw cottages” in which “natives” made “mats, manufacture leis and poi and pursue other vocations.” Taliesin Evans’s guidebook noted its cyclorama that provided a “realistic representation of the burning crater of Kilauea.” Visitors were also treated to an exhibition of “two empty ‘throne’ chairs that formerly were owned by Kamehamehali and Kalakaua, and that a little over a year ago were wrested from the possession of Liliukalani by the Provisional Government of Honolulu.” The fact that the Monarch Souvenir deemed the Hawaiian Village “truly representative” was identified as being particularly important because “recent events” had “created a desire in the public mind for a more intimate knowledge of the Hawaiian people.” “Recent events” was a euphemism for the United States’ imperial maneuvers on the islands. As the reporter for the Call explained, “in permitting the transportation of these idle baubles of a deposed dynasty to a foreign land,” the American sugar plantation owners who had taken control of the island “intended to give notice that these things would never again be needed at home.” However, this account also noted that the “native islanders who serve as attendants in the Hawaiian Village” maintained “a different view.” Instead of happily accepting the overthrow of their queen and agreeing that the chairs they were exhibited with symbolized her defeat, they looked “hopefully” to the time when she would “be re-enthroned” on one of the chairs. Hawaiians, seen from this vantage point, did not appear to be the kind of willing, passive subjects that would be easily assimilable into the American national fold. In fact, the issue of the desirability of Hawaiians as American citizens hovered over the subject of Hawaiian Annexation, which was debated at the inaugural meeting of the Midwinter Fair Congresses, on January 25, 1894, two days before the fair’s official opening. Although the side opposing annexation in the debate was declared the winner, this—according to the judges—was “decided merely on the strength of the arguments and did not attempt to offer any suggestion in regard to the solution of the question of annexation.”(16)

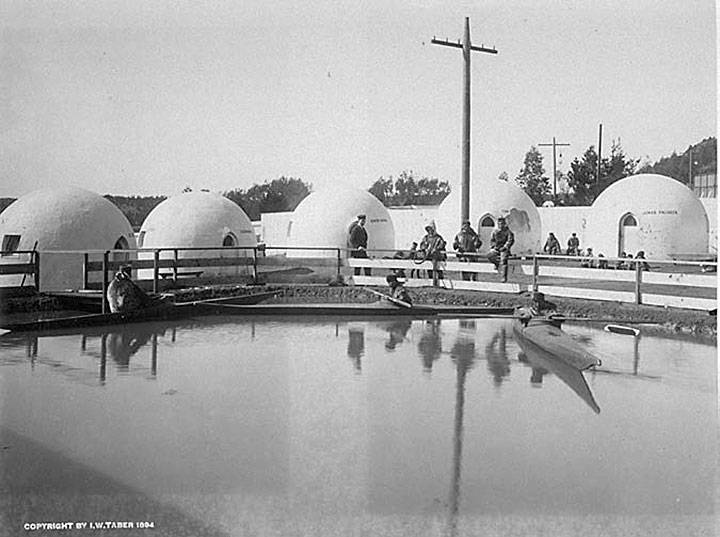

While the Hawaiian Village represented many of the ambiguities that surrounded the issue of American imperial adventures and conveyed an image of Hawaiians as possibly unwilling and probably undesirable Americans, the Inuit exhibits represented “Esquimauxs” as more thoroughly conquered, docile, physically weakened, and childlike. The Esquimaux Village occupied three acres at the fairgrounds and displayed the “mode of homelife” of Inuit people from both Labrador and Alaska. The exhibit featured igloos made from plaster staff, a lake, canoes, sealskin tents, and sled dogs. It offered, according to the Monarch Souvenir, an excellent way to learn about Inuits, “whose ways of living are so peculiar and whose race characteristics are so little known to the civilized nations of the world.” The issue of integration in the American body politic was not as acute as in the Hawaiian case, in part, because Inuits at the fair conformed to prevalent understandings of Native Americans as, what the Chronicle termed, a “rapidly diminishing race of people.” This image was reinforced by a tragically high infant mortality rate among the Inuits at both the Chicago Fair and the San Francisco Fair. All five of the children born to Inuits during the tenure of these two fairs died as infants.(17) Moreover, because Inuits were also perceived as childlike and thus naturally dependent and in need of protection, resistance to American dominance was not expected to be forthcoming. This image was reinforced by Chronicle reports of Inuits at the fair, who when left to their own devices were found “dropping dimes into the cocktail and rum slots of the automatic bar” and not attending educational exhibits geared more toward “the elevation of the race.” Accounts in the Chronicle of their shopping trips downtown emphasized their attraction to shiny, childlike things: “gold watches and toys.” Within three years, the Klondike gold rush would send Americans pouring into Alaska and thus add a new dimension to the conquest of the Inuits already well under way.(18)

The Esquimaux Village. The Midwinter Fair’s exhibits of Inuits and Hawaiians occurred in the context of debates about whether or not such newly colonized peoples would make suitable citizens.

Photo: I. W. Taber, photographer. Souvenir of the California Midwinter International Exposition 1894, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

Although the representations of Asians, Pacific Islanders, and Native Americans that emanated from these concessions were frequently negative, this did not stop exhibited peopled from partaking of aspects of some of these same Orientalist displays and participating in both the elaboration and disruption of the fair’s ordered vision. On Sundays when the Esquimaux Village was closed, Inuit men explored the fairgrounds, taking in all the other shows, and both men and women traveled downtown on shopping expeditions. Special celebration days, like Chinese Day on June 17 and Japanese Day on June 9, complete with parades and pageants, drew large numbers of Asian patrons to the Midwinter Fair even though—or perhaps because—people of Asian descent had to struggle harder than other ethnic and fraternal groups to have these days set aside for them.(19) Numerous accounts drew attention to the wide-ranging participation of Chinese at the Midwinter Fair. The Official History remarked upon the “liberal patronage accorded the general features of the Exposition by the large Chinese population of San Francisco.” The Chronicle reported that the young actors from the Chinese theater roamed the fairgrounds when not working and were apparently very fond of “the nickel-in-the-slot contrivance in Machinery Hall.” During the fair’s run, Chinese fair-goers regularly attended the Chinese theater, thoroughly enjoying an experience that many white patrons found educational but distasteful. On the day that the Chinese Building opened, a Chronicle report related, “The Chinese themselves took a huge interest in the exhibit and the place was thronged all day.” This account noted that the merchants and tourist entrepreneurs “in charge” were “mightily proud of their building.” They “conducted visitors to the joss house,” while in the “reception room” a “cultured Chinese . . . explained the hidden meaning of the wondrous works of art which adorned the walls.” These men aided and abetted the Midwinter Fair’s Orientalist fantasy by presenting an image of the Orient that, to non-Asian visitors, likely came across as reinforcing the difference, strangeness, and barbarism of people of Asian descent. However they also created a space that San Francisco’s Chinese could participate in and succeeded in representing Chinese culture in ways that this local community could respond to with enthusiasm and pride.(20)

White man pulling a jinrikisha at the Midwinter Fair. Despite fair organizers’ hopes, Japanese men refused to pull jinrikishas at the fair because of the degrading nature of the work. White men in Japanese garb were employed to take on the task instead.

Photo: I. W. Taber, photographer. Souvenir of the California Midwinter International Exposition 1894, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

The story of the jinrikishas at Sunset City, however, attests to the fact that there were limits beyond which people of Asian descent refused to go in the creation of an Orientalist version of their heritage. In the context of the Midwinter Fair, a “jirinkisha [sic]” was, according to Taliesin Evans’s guidebook, “a conveyance used for the rapid transportation of visitors around the Fair grounds.” It was “drawn by a human beast of burden at a fixed rate per trip or by the hour, at the pleasure of the person hiring the conveyance.” The jinrikishas at Sunset City were acquired from Japan by George Marsh, the same Australian Orientalist who commissioned the Japanese Tea Garden. Mr. Marsh and others had hoped that jinrikishas would be pulled by Asian men and thus provide a form of transportation for fair-goers that would fit nicely with the Sunset City’s Orientalist theme. To their dismay, they discovered that the jinrikisha was, as Evans related, “very unpopular with the natives of Japan” because it was “regarded as a dreadful degradation to be impelled to haul one.” In fact, the Examiner published a portion of a petition that publicly articulated the extent of the Japanese community’s opposition to the use of jinrikishas at the Fair. It had been “sent to the Midwinter Fair Executive Committee, the Supervisors and the Park Commissioners, signed by the Japanese residents of San Francisco and by M. C. Harris and E. A. Strong, in charge of the local Japanese missions.” It read:

Gentlemen: We, the undersigned, desire respectfully to call your attention to a minor incident in connection with the Exposition, which is, however, of very considerable interest to the Japanese residents of San Francisco, and is also calculated to excite more or less discussion in Japan. We allude to the contemplated use of the jinrikisha. There can be no valid objection urged to the mere exhibition of the jinrikisha at the Midwinter fair, but there are other circumstances in this connection of which in all probability you are not advised. . . . The custom of requiring the jinrikisha to be drawn by men instead of animals is degrading and should not be encouraged in a civilized Christian country like America. We, consequently, respectfully and earnestly protest against its use in this manner in the Park or upon public streets during the Fair.

“The petition,” the Examiner continued, “then gives as reasons the fact that the practice is injurious to the health of the men who draw the vehicles; that it is a disgraceful and inhuman custom; that it is incompatible with the grand aims of the Midwinter Fair as an elevator of humanity.” For Japanese immigrants, making such a statement was certainly a bold move. They had only recently begun to come to the mainland United States, settling primarily in California. As a group they possessed more education and were better-off financially than most European immigrants. Perhaps with guidance from their missionary friends, their use of the petition showed that they were not only unafraid to register their grievances but that they were politically savvy enough to do so in a form that smacked of Western traditions and played on notions of who, the Japanese or the Americans, was truly civilized.(21)

The petition, combined with the opinion of the Japanese community that it expressed, succeeded in keeping Japanese from manning the jinrikishas at Sunset City. It did not, however, dissuade Midwinter Fair officials from deploying jinrikishas at the Fair. Perhaps this was because jinrikishas were such a part of their Orientalist fantasy that exposition officials could not part with them. Maybe it had something to do with the contractual arrangements already made with Mr. Marsh. In any event, Sunset City had its fleet of jinrikishas and they were pulled by white men of various nationalities costumed in face-paint and Japanese garb. As the Monarch Souvenir explained, “The feeling of opposition to the introduction of man-power from Japan was so great that none except white men could be induced to do the work.” An article in the Overland Monthly intimated that this was less than effective in achieving its desired objective, “At a distance of a half a mile a jinrikisha runner might be taken, possibly, for a Japanese, but at nearer view disenchantment must follow. The broad Hibernian face and the characteristic roll of the large figure are rendered grotesque by the tiny cap and skin-tight suit.” The decision to employ white men as jinrikisha drivers also had some unintended consequences. On Japanese Day many Japanese women rode in jinrikishas as did both men and women of Chinese descent on Chinese Day. It “increased the standing of a swell Mongol,” the Chronicle reported, “to be seen scudding along through the rain in the vehicle, smoking an Early Grave five-cent cigar.” Despite the derogatory language, it probably did increase the standing of Asian men and women—or at least temporarily disrupt the racial hierarchy—to be pulled along in a hired jinrikisha by a white man dressed like a Japanese.(22)

Notes

1. See Arthur Chandler and Marvin Nathan, The Fantastic Fair: The Story of the California Midwinter International Exposition, Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, 1894 (St. Paul, MN: Pogo Press, 1993). De Young’s motives are further elaborated in the Official Guide to the California Midwinter Exposition, 1st ed., Compiled from Official Sources under the Direct Supervision of the Exposition Management (San Francisco: George Spalding, 1894), 19; The Official History of the California Midwinter International Exposition: A Descriptive Record of the Origin, Development and Success of the Great Industrial Expositional Enterprise, Held in San Francisco from January to July 1894 (San Francisco: H. S. Crocker, 1895), 11–24; and James D. Phelan, “Is the Midwinter Fair a Benefit?” Overland Monthly, 2nd ser., 23 (April 1894): 390 –392.

2. According to Chandler and Nathan’s calculations the exposition netted a profit of $66,851.49. See Fantastic Fair, 67. Funding of the Midwinter Fair was based solely on popular subscription. Contributions from ordinary San Franciscans were comparatively more generous than those from wealthy firms and individuals. In the midst of the economic crisis, federal, state, or municipal financing was an impossibility. See Official History, 11–22. Attendance figures are based on Chandler and Nathan, Fantastic Fair, 77. To provide a sense of scale, 27,529,400 people attended the Columbian Exposition. See Robert Rydell, All the World’s a Fair: Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, 1876–1916 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984), 40.

3. Official History, 11–24; Phelan’s speech was reprinted in Official History, 74–75. San Francisco native James Duval Phelan was a prominent banker, civic leader, and proponent of the City Beautiful movement. In 1897, he was elected mayor of San Francisco and served three two-year terms. In his opening remarks, he quoted Social Gospel Movement founder Josiah Strong’s “Anglo-Saxon Predominance” from 1891. Strong was quoting John Adams.

4. Official History, 48 and 47. See also Official Guide, 25. When the Midwinter Fair is mentioned in the historical literature at all, it is routinely dismissed as being “largely imitative” of the Chicago Fair. See Rydell, All the World’s a Fair, 51. Although the Midwinter Fair did import many exhibits from Chicago, the idiom of exposition design was already well articulated prior to the Chicago Fair. Moving exhibits to San Francisco, a different setting with distinctive architecture, changed local conditions, plus novel added exhibits made for a decidedly distinct exposition experience. My understanding of nineteenth-century expositions has been shaped by: James Gilbert, Perfect Cities: Chicago’s Utopias of 1893 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991); Alan Trachtenberg, The Incorporation of America: Culture and Society in the Gilded Age (New York: Hill and Wang, 1982); Gail Bederman, Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880–1917 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995); Rydell, All the World’s a Fair; and William Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West (New York: W. W. Norton, 1991).

5. Descriptions of the buildings come from The Monarch Souvenir of Sunset City and Sunset Scenes: Being Views of California Midwinter Fair and Famous Scenes in the Golden State (San Francisco: H. S. Crocker, 1894) and Official Guide, 43, 55, 67. For more detail about the architects and architecture of the Midwinter Fair, see Chandler and Nathan, Fantastic Fair and Kevin Starr, Inventing the Dream: California through the Progressive Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 190 –193.

6. Official History', 47.

7. The seminal work on Orientalism remains Edward W. Said, Orientalism (New York: Pantheon Books, 1978).

8. Taliesin Evans, All about the Midwinter Fair, San Francisco, and Interesting Facts Concerning California, 1st ed. (San Francisco: W. B. Bancroft, 1894), 24. The city had also long been secure in its imperial dominance of its regional hinterlands. See Gray Brechin, Imperial San Francisco: Urban Power, Earthly Ruin (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999). As a result of the Spanish American War the United States acquired varying levels of dominion over Cuba, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

9. David Gebhard, “One Hundred Years of California Architecture,” in David Gebhard and Harriette Von Breton, eds., 1868–1968, Architecture in California, An Exhibition Organized by David Gebhard and Harriette Von Breton to Celebrate the Centennial of the University of California, The Art Galleries, University of California, Santa Barbara, April 16 to May 12, 1968 (The Regents, University of California, 1968), 7, 16; and Official Guide, 16. See also David G. Gutiérrez , “Significant to Whom?: Mexican Americans and the History of the American West,” Western Historical Quarterly 44, no. 4 (November 1993): 519–539, and Carey McWilliams, North from Mexico: The Spanish-Speaking People of the United States (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1949), 36, who coined the term “Spanish Fantasy Heritage” to describe this kind of appropriation.

10. The outline of the Midwinter Fair’s Grand Court of Honor exists today as the Music Concourse in Golden Gate Park. Until 1921, the Fine Arts Building served as San Francisco’s first public art museum, the De Young Memorial Museum, in memory of the Midwinter Fair.

11. Evans, All about the Midwinter Fair, 1st ed., 75, and Official History, 146, 47.

12. California Midwinter Exposition Illustrated, Official Souvenir: Illustrations and Descriptions of All Prominent Buildings, Biographical Sketches, Synoptical History of Early California, Notice of Concessions, etc. (San Francisco: Robert A. Irving, 1894), npn.

13. Official History, 150, and Official Guide, 100 –101. See also San Francisco Chronicle, March 22, 1894, and Nathan and Chandler, Fantastic Fair, 46. The Chinese government refused to set up an official exhibit at either the Columbian Exposition or the Midwinter Fair in protest over renewed restrictions on Chinese immigration.

14. This concept of differential racialization based on distance or proximity is developed by Robert G. Lee, Orientals: Asian Americans in Popular Culture' (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1999), 27–28; Official Guide, 100 –101. See also San Francisco Examiner, January 28, 1894.

15. Evans, All about the Midwinter Fair, 2nd ed., 168, 175; and Monarch Souvenir of Sunset City. This description is also drawn in part from Chandler and Nathan, Fantastic Fair, 42. They note that “The Japanese Tea Garden was so popular an attraction at the exposition that the Golden Gate Park Commissioners purchased it from Marsh at the Fair’s end and it has since remained one of San Francisco’s most beloved possessions,” 42.

16. San Francisco Morning Call, October 31, 1893; Evans, All about the Midwinter Fair, 2nd ed., 150; Monarch Souvenir of Sunset City, npn. See also Chandler and Nathan, Fantastic Fair, 19. For debate over Hawaiian Annexation, see Chronicle, January 26, 1894; Official History, 256; Chronicle, February 26 and 28, 1894.

17. Official History, 162; Monarch Souvenir of Sunset City; and Chronicle, March 24, 1894. On February 10, 1894, Francisca Tehama Deer had been born in the Esquimaux Village. She died in early April. Four Inuit children had been born at the Columbian Exposition and all but one had died within a week of their birth. The surviving baby, Christopher Columbus Poliseer, died in San Francisco on April 10, 1894. At least one of these children was reported to have died of hereditary syphilis. See Chronicle, March 10, 1894; Call, April 11, 1894.

18. I have chosen to use the term Inuit rather than Eskimo since It is the current and, I hope, most respectful designation. I use Esquimaux when referring specifically to the village, since it was called the “Esquimaux Village,” or when citing specific sources that used that term. Chronicle, February 26 and 28, 1894.

19. Chronicle, June 18, June 17, June 9, 1894. Chinese Day was announced in May, while the special days of other groups were announced in the press on January 8, 1894, and were published in guidebooks and other fair literature. Its initial announcement stated that it would take place on June 7, but it was actually held the last Sunday of the fair, June 17. These facts suggest that Chinese Day was awarded not only belatedly but also reluctantly. Similarly, Japanese Day was only listed in one guidebook and there it was assigned the wrong date, March 9. The Midwinter Fair did not feature a special day for Native Americans. It did host a Hawaiian Day that was, however, as much if not more about the United States’ imperial ambitions than about native culture. The Midwinter Fair hosted an African American day that seems to have been awarded without the struggles of the Chicago Fair. Perhaps the Executive Committee had learned a lesson from the Columbian Exposition or perhaps African Americans—a small population in San Francisco compared to Asians—did not pose the same kind of threat to whites. See Chronicle, May 1, 1894; Evans, All about the Midwinter Fair, 1st ed., 85.

20. Chronicle, February 28, 1894; Official History, 150; Chronicle, April 1, 1894; and Chronicle, February 18, 1894.

21. Evans, All about the Midwinter Fair, 2nd ed., 153; Examiner, January 20, 1894; Monarch Souvenir of Sunset City, npn. In 1889, Article 30 of the Constitution of the Empire of Japan gave citizens the right of petition during a period in which Japan adopted new forms of Western-style governance. Voting rights for all men were not granted until 1925. See Arthur Tiedemann, Modern Japan: A Brief History, rev. ed. (Princeton, NJ: D. Van Nostrand, 1962). For information about Japanese immigrants, see Ronald Takaki, Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans (New York: Penguin Books, 1989), 42–53.

22. Elisabeth S. Bates, “Some Breadwinners of the Fair,” Overland Monthly, 2nd ser., 23 (April 1894), 374–384; and Chronicle, June 17, 1894.

Originally published as chapter 5 “Imagining the City: The California Midwinter International Exposition” in Making San Francisco American: Cultural Frontiers in the Urban West, 1846-1906 by Barbara Berglund (University Press of Kansas: Lawrence KS 2007)