Roots of Urban Resistance, 1998

Historical Essay

by Richard Walker, 1998

This is an excerpt from "Appetite for the City," originally published in Reclaiming San Francisco: History Politics Culture (City Lights Books: San Francisco 1998), ed. by James Brook, Chris Carlsson, and Nancy J. Peters

The contrariness of San Franciscans to the annihilation of their city has been exceptional, as has the success of antidevelopment politics. Simple defense of living space and neighborhoods against the wrecking ball has played its part, to be sure, and so have the organizing efforts of dedicated radicals and the peculiarities of local political structures. But these visible parts of civic resistance need roots and soil to grow in, and here San Francisco demonstrated for a time a most favorable economic, political, and cultural substratum.

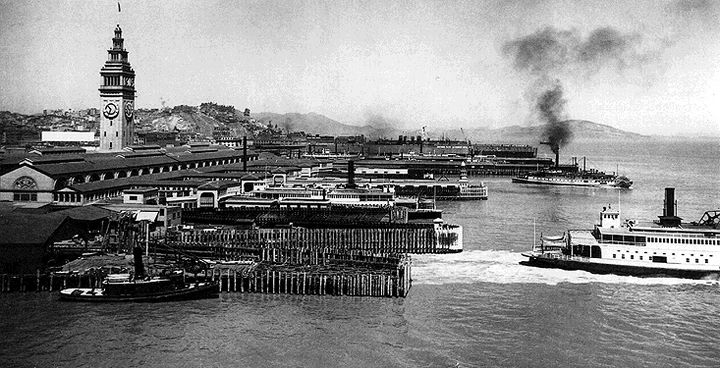

The Embarcadero Freeway separates the Ferry Building from the city in this 1958 photo. The Ferry Plaza had been a central gathering point for generations of San Franciscans and visitors prior to marching up Market Street.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Under the Economic Volcano

Economics undergirds so much, and it is hard to escape San Francisco’s legacy of wealth. Cities have been wellsprings of modernization and modern life because of their capacity to siphon wealth from many corners of the land (and overseas), concentrating and multiplying it in a narrow space. California has, moreover, been one of the greatest engines of economic growth in the world over the last fifty years. While Los Angeles outgrew its northern rival before World War II, the Bay Area has been singularly favored by the wars in the Pacific, its financial complex, and the growth of electronics.

That prosperity erected new pyramids downtown, but also helped generate opposition to the business vision of civic progress. It brought many new residents to the city in the first place, as California’s booming economy generated millions of jobs and supported a large public sector. This magnetic field of opportunity drew everyone from ex-GIs enrolling at the Art Institute in the 1940s to computer hackers in Multimedia Gulch in the 1990s. It called up people of every class, from the professionals in the Marina district to immigrant workers in the Mission. It provided a cushion for those who did not come for economic reasons, whether beats, students, hippies or gays, and allowed them the freedom to create subcultures that reinvigorated the city. The mass character of those bohemian elements was unprecedented, and can only be explained by the economic liberation of the young. The civic surplus even supported many of those who explicitly opposed redevelopment, whether businessmen like Duskin, bohemians like Lawrence Ferlinghetti, or gay activists like Milk.

Prosperity worked its magic more effectively as long as rents remained low enough to allow artists, refugees, and those outside the mainstream to survive, if not prosper, in the inner city. The long slump in central-city investment due to depression, war, and suburbanization had left property markets relatively untouched for two decades. The confluence of economic growth without property speculation through the 1950s was ideal for nurturing the countercultures that mushroomed in San Francisco. Conversely, the heating up of real estate in the seventies and eighties drove out many of the marginals; as old commercial space disappeared, the affluent crowded into gentrifying neighborhoods, and mortgage markets overflowed with easy credit.

A Republic in Miniature

American leftists are prone to beg the question of the origins of urban protest by reference to grassroots movements and to reject any class analysis of such upheavals. Others refer vaguely to the middle-class character of the antigrowth movement. Neither interpretation will do. In San Francisco the balance of classes has tripped up the business elite in their efforts to command the civic skyline. The Downtown capitalists do not rule the roost in so clear-cut a fashion as in other cities. This weakness (relative, to be sure) is sometimes attributed to schisms such as those between the Spreckels and DeYoungs or Giannini and the Anglo-Saxons of Montgomery Street, but there is little evidence for a falling out in the postwar era within San Francisco, when the real fight was with the East and South Bay. Instead, difficulties came from below, and from three different directions.

To begin with, San Francisco has a curiously skewed class distribution because of its role as a commercial, financial, and corporate center as well as a government and public service node that is heavy on administration, education, medicine, and foundations. The division of labor tips toward upper-level managers, professionals, and technical workers, including doctors, lawyers, journalists, accountants, computer programmers, and administrators. This makes the city’s class structure bulge in the middle. Add to this the skilled workers who keep business and the city running through supporting roles in printing, electrical, office machines, carpentry, technical writing, and the like, and the working class skews upward as well, with wages well above the national average.

At the same time, the workers of San Francisco have historically been well organized and able to hold their own against the bully-bosses, through union militancy and political activism. Racial exclusion reinforced working-class strength and the sense of rough equality among European Americans of diverse backgrounds. At the end of World War II, San Francisco was a union town and working-class leaders were powers to be reckoned with. Although key unions cut a deal with big business and Mayor Alioto to support Downtown building, many workers still carried memories of militancy and class hatreds in their trouser pockets. This is manifest in the old Filipino, white, and black longshoremen, and sailors fighting against the destruction of their hotels. Worker empowerment and good wages fueled class struggles rather than dousing them, brought alliances between skilled and unskilled male workers, and blurred the edges between the working and middle classes.

Finally, rapid growth and personal mobility have had a permanently destabilizing effect on the class system, top to bottom. The massive influx of people into California, and rapid turnover at all levels, has frequently meant that class allegiances are poorly formed, with individualism in the ascendant. Moreover, a certain wage and rank mobility and the rapid formation of new businesses by aspiring people of skill (from Esprit to Wired) has reinforced individualist aspirations. The effect has been to strengthen the middle-class outlook of San Francisco, a further petty bourgeoisification at the expense of both ends of the class spectrum. Curiously, this has not made San Franciscans less but, instead, more liberal, and even libertarian, in the face of power plays by big business. This contrasts with Los Angeles which, with a similar class structure, has always been more conservative.

Lifelines of Liberality

Politics is more than the geometry of class forces, and the liberal bent of San Francisco’s citizenry cannot be explained by the mere presence of a working-class or petty bourgeois bloc among the electorate (nor by race, in the white postwar era). Electoral politics have been so progressive that they have won San Francisco the moniker “Left Coast City,” making it a liberal island in a sea of California Republicanism. Voting patterns have a clear geography, with the east of Twin Peaks tilting consistently to the left (with its own political microgeography based on race, class, and sexual orientation). Worse for the business interests, the east side has been the part most impacted by development.

Behind this liberalism lies a political culture forged out of the class standoff between capital and labor in the early twentieth century. That political culture includes high voter turnout, political clubs, freewheeling initiatives, and weak mayors. Capital could not vanquish labor from the political landscape of the city, so it has had to go through progressive Republicans such as Sunny Jim Rolph and Warren Christopher or pro-growth Democrats such as Joe Alioto and Willie Brown to get its business done without mobilizing class opposition. At the same time, a liberal Democratic party apparatus could be stitched together that owed little to capital, as was done by Harvey Milk’s Gay Democratic Club, and Phil Burton, who became a civic, state, and national power from the 1950s to the 1980s.

Part of the aims and accomplishments of this political culture has been to dispose middle-class people toward organized labor and to weaken their allegiance to the burghers of Pacific Heights. This sort of position is rarely rationalized in terms of class, but rather as libertarian independence from all power blocs and sympathy toward the oppressed. As a result, any number of transgressive political bridges were constructed in the postwar era across conventional boundaries of class and race formation. Harvey Milk organized gay men across the class spectrum, turning personal liberation into political power. Burton got his start by uniting Chinatown and white workers of the hotel districts, then brought in middle- and upper-class liberals from the eastern half of the city. Civil Rights activists and the Burton machine forged alliances between African Americans protesting black removal and white liberals opposing Downtown expansion. Meanwhile, the beats and hippies contributed by their rebellious race-mixing and incorporation of black culture into their practical critique of the oppressions of bourgeois expression and repression.

A Taste for the City

Neither can politics stand alone as an explanation for widespread opposition to the spatial incursions of the Downtown. The protagonists of urban preservation were inspired by more than distaste for capitalist power plays, particularly since so many of them were (petty) bourgeois in background or aspiration. Nor were they simply defending hearth and home. People rallied to protect urban life as they knew it. The everyday urbanity of San Francisco is undergirded by a webbing of popular culture and public vitality that sustains the city; the wellsprings of affection for urban life flow from many quarters. All opponents of redevelopment, of whatever origin or neighborhood, had experiences of urbanism to draw on and visions of civic space as a public good. These experiences inspired people and got their backs up against the destruction of San Francisco (often after drawing them to the city in the first place). Such urbanity is rarely taken into consideration by leftists, even proponents of the postmodern turn. Yet the density, commingling and variety of the city, and inhabitants’ ordinary encounters with the urban world, have real effects on consciousness and action.

It helps that San Francisco had a rich cosmopolitan tradition to begin with. The city was the urban oasis of the West in the nineteenth century. The Victorian makeover of the last quarter of the century rebuilt the city as a stage set of middle-class rowhouse respectability and upper-class pomposity, but left the vast redoubt of the working class lying South of Market, and the public secrets of the Barbary Coast and the waterfront on full display. After half the city was erased in the catastrophe of 1906, San Francisco was rebuilt along radically new, vertical lines. The central districts were reconstructed at a much higher density as hotels and apartments. Thousands of multiple housing units were purpose-built for businessmen, saleswomen, clerks, longshoremen, and the whole gamut of the urban labor force. These were, moreover, intentionally done in a modern style, with the latest improvements, as an explicit alternative to the suburban house; these were meant to be homes for urban living. This was the high tide of dense urbanism, full of pedestrian life, bright lights, and popular entertainments along the Great White Ways such as Market, Mission, and Fillmore. Many San Franciscans still occupied this urbane space after World War II, long after it had been junked in favor of the suburban model for American cities.

The rebellion against Downtown was not fought by denizens of the past but by the city’s postwar occupants, many of whom were new arrivals. At the very moment when most Americans were fleeing the central cities, others fled in droves to San Francisco to escape dystopian suburbs and to create their own utopias. This was urban renewal of a different stripe. It brought African Americans into the Fillmore district during the war, along with the first gays discharged from the military. Next came former GIs who had seen the city in passage from Toledo to Guam and had fallen in love with it. The pioneering beats drifted in after the war, finding refuge in North Beach and the Fillmore; they were joined by growing numbers of alienated white youths in the 1950s. Students came from around the country, swelling the ranks of those cutting ties to bourgeois domesticity.

After the beats established San Francisco as the countercultural capital of postwar America and student rebellion heated up in Berkeley, the Bay Area became a new sort of urban oasis. Hippies overran the Haight, a district on the decline (bordering the Fillmore), with spacious Victorians and cheap rents. Gays flocked to the queer Mecca of the Castro district in the 1970s (the Castro was another working-class neighborhood emptying out). Gay liberation jump-started the yuppie era and its celebration of personal indulgence among the well-paid middle classes spawned by Downtown’s office revolution.

For the beats, hippies, gays, and yuppies the city itself was an object of celebration as well as a place of liberation. More than housing, it promised tolerance, promiscuous mixing, cheek-by-jowl density, public life, and a landscape to delight the eye. The beats fit easily into North Beach’s Italian community, with its traditions of anarchism, café chatter, and public display. Beat sculptors used the rubble of building demolitions for their found art. Lawrence Ferlinghetti, a founder of City Lights Bookstore, was a protester at the razing of the Montgomery Block. A local judge refused to censor Allen Ginsberg’s Howl. Hippies painted up the Victorians of the Haight, held their Be-ins at neighboring Golden Gate Park, and listened to rock in the nearby Fillmore Auditorium. Urban space served as a critical resource for the flowering of gay life, providing collective self-affirmation and protection in the face of a hostile world. Few people outside the police department gave a damn about enforcing heterosexuality. Gays pioneered the improvement of Victorian housing and the South of Market, and they were leaders in the preservation movement. Yuppies had good, city-based jobs and bought city homes to go with them. They sought the kind of urbane culture they had witnessed on student travels to Europe and Latin America, and took to gentrifying Victorian and Edwardian neighborhoods with a vengeance.

Contrary Spirits

Along with the spirit of urbanism, San Franciscans, particularly intellectuals, have moved in counterflow to mainstream ideas of modernity. Despite living at a crossroads of American capitalism, where money, commerce, industry, and commodities bray from every corner, they developed a critical distance from the sirens of modernism and modernization. In short, they never bought wholeheartedly into the ideology of progress. This was by no means true of nineteenth-century San Francisco, the Las Vegas of its time. Over the years, the lust for money-making at the cost of land and landscape had been blunted.

The first meek turning away came as San Francisco’s second generation bourgeoisie sought to erase its ragtag origins in the mining districts and create a semblance of civilized urbanism modeled after eastern cities. San Francisco’s burghers eschewed the sinewy modernism of Chicago in favor of Victorian fiddle-faddle (though such buildings were thoroughly modern in construction). A second turning away came at the end of the century, when third-generation burghers rejected Victoriania but also refused the modernism of Prairie or Bauhaus for the historicism of the Shingle, Renaissance, and Mediterranean styles. More generally, they fell under the sway of the Arts and Crafts movement; nowhere was the radical romanticism of William Morris embraced more fervently than in California. So dominant was the cultivated rusticity propagated by Bernard Maybeck that modernism finally came to the Bay Area in the 1930s clad in redwood and rough-hewn planks suitable to the regional myth of the naturalized city. Contrast this with Los Angeles, which abandoned historicism in favor of high modernism in the 1920s, and never looked back.

August 31, 1954, the ferry Eureka approaches the Ferry Building.

Charles Cushman Collection: Indiana University Archives (P07299)

Ferry Building with departing ferries, 1912

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

The leading contrarian of the Progressive era was John Muir, a mechanic and naturalist turned rustic bohemian and transcendental mystic, whose crusading zeal and savvy propaganda for the mountains of California launched the American environmental movement. The most popular writer of the time was Jack London, and Frank Norris was not far behind. Both made nature the backdrop for their greatest novels, while pushing the critical reach of literary realism to the limits of respectability. And both, despite their contrasting social origins, were thoroughly imbued with the petty bourgeois streak of independence and self-righteousness of their home city. Journalists Lincoln Steffens and Upton Sinclair were cut of the same cloth, one moving east and the other west in the course of their careers.

The New Deal era found San Francisco at the head of labor upheavals with the General Strike of 1934 and the cultural turn toward social realism in painting, photography, and literature, another flux of contrary modernism. Diego Rivera spent his first years in the United States working here, where he left a host of local acolytes. Dorothea Lange, Paul Strand, and the f64 movement redefined photography both in subject matter and in art. Ansel Adams broke away to follow Muir’s vision of pristine nature. Contrarian writers nurtured in isolation around the region between the wars included Robinson Jeffers, Henry Miller, and Eugene O’Neill.

After the war, San Francisco was propelled from cultural Hill Station to the global focal point for a generation of youth rebellion and countercultural experimentation. Many beat writers were restless New Yorkers drawn to San Francisco because their sort of ragged poesy and vagabondage was irresponsible, even deplorable, in New York’s literary and political hothouse. San Francisco offered the right combination of urbanity and obscurity to ferret away New York’s mantle as the cultural capital of modernity, and to begin in a marginalized, noncommercial, anarchistic way to stumble toward postmodernism. When realism gave way to abstraction in the visual arts, San Francisco leapt on the boat from New York in the glory years of abstract expressionism at the Art Institute in the late forties. But the counterflow of local culture twisted back into a figurative turn in the 1950s and, in the hands of Bruce Conner, Wally Hedrick, and Jess, shifted constructivism toward the political art of the 1960s. Musically, black jazz briefly merged with white poetics; then the Bay Area sound of Dave Brubeck went off on its own iconoclastic tangent.

The Beat Generation slid easily into the rebellious sixties, with politics and counterculture in closer dialogue in the Bay Area than anywhere else. Rock was the voice of the new generation and San Francisco’s Fillmore Auditorium the launching pad for its most innovative bands, such as Big Brother and Jefferson Airplane, or the black-white combustibles of Sly and the Family Stone and Tower of Power. The most enduring were those epigones of laid-back licks, the Grateful Dead. Psychedelic poster art was a kind of Jugendstil gone mad, while clothing took a lurch back to Victoriana. A familiar strand of the counterculture was an affection for nature, running from Kenneth Rexroth, the key intellectual bridging the 1930s and 1950s, to Gary Snyder, beat poet and Zen master of bioregionalism today. Disaffected hippies and students took to the countryside by the end of the sixties, seeking a rural utopia after their urban one had failed.

Gays were largely white and middle class and had more disposable income than earlier countercultures; nonetheless, they were social pariahs. They elevated the joyful abandon of civic sinning to a level not seen since the closing of the Barbary Coast. Gay liberation exceeded even the beats and hippies in its flouting of social convention and confirmed San Francisco’s reputation as a refuge from small-minded America. On the other hand, the counterculture’s rejection of consumer culture was swamped by the hedonistic rush of gay pleasure-seeking (not without contradiction: hedonism fell afoul of the AIDS epidemic and consumerism split the well-heeled from poor gays and lesbians).

As the eighties dawned, the San Francisco counterculture had achieved an unexpected degree of mainstream acceptance. The yuppie consumer culture carried some of the spirit of refusal against American domestic rectitude, ushering in the “latte leisure class,” as well as gay sensibilities in architecture, dress, and the arts. The yuppies’ affluence and consumerism eroded the radical basis of urban culture, but distinguished the Bay Area’s petty bourgeoisie as a world-historical force in the realm of consumption: nouvelle cuisine, hot tubs, wines, personal computers, the Nature Company, backpacking gear, New Age music, Esprit and Gap clothes, and more spewed from this fount of liberatory self-indulgence.

The beats, hippies, and gays represented a very ungenteel sort of bohemianism that was more confrontational, more political, and more bizarre than ever before in this country. Rexroth, Ginsberg, and the rest showed a ferocious independence and spiritual refusal to follow orthodox parties, preferring a left anarchism that is a touchstone of San Francisco’s political culture. The New Bohemianism was absolutely critical in forming the political consciousness and urbane outlook of the Bay Area, moving the middle class decisively to the left of the American mainstream, celebrating the frightful asymmetries of urbanity and re-igniting a radical romanticism that went far beyond the aesthetics of Arts and Crafts, the mystical environmentalism of John Muir, or the manly socialism of Jack London.

What Next?

San Franciscans can be justly proud of their record of opposition to the bulldozer of progress, but such resistance has decided limits. Downtown expansion was contained on the north and west, only to cross Market Street and trigger the radical transformation of the South of Market to Mission Bay. Property speculation fell into the doldrums for a decade after 1985, but has picked up again. Downtown’s growth is limited more by the property cycle than by social protest. As the city’s economy went into the tank in the worst depression in fifty years, job loss (30,000 in San Francisco) laid waste thousands of lives. Political conditions around the state and the country have deteriorated, as the triumphant demagogues of the right put the screws to urban Democrats, the intelligentsia, working people, immigrants, and the poor. Even in San Francisco, bourgeois reaction is out of the closet, where popular struggles had locked it up for half a century, and the ruling class is more interested in sweeping the streets of the homeless and cutting wages than in meeting the needs of the people.

Meanwhile, the wellsprings of opposition have been drying up. The left is worn out, gays have been preoccupied with AIDS, yuppie exuberance is gone. High rents put the squeeze on the counterculture, and outcast youth today are more likely to be homeless than bohemian. Wages and union strength have eroded, and the working class has been recomposed as largely foreign-born Asian and Latin peoples who face greater obstacles than their white predecessors, and whose political and organizational presence is just awakening. At the same time, the skilled hotshots of computing, multimedia, and brokerage are more inclined toward monetary payoffs and expensive cars than to the public duties and pleasures of civic life. A fine and noble epoch is over and done with much as the Gold Rush era of libertine opportunity faded away in its time. San Francisco has not sunk as far as the rest of America (Dole got only 17 percent of the vote in 1996), but the survival of the city as a decent place to live is by no means assured.

References

THE BEST CASE FOR THE PECULIARITY of San Francisco’s petit bourgeois class structure is still Carey McWilliams, California: The Great Exception (New York: A. A. Wyn, 1949). I make the same argument for recent years in Walker et al., “The Playground of US Capitalism?” This view is rejected, I should add, by Peter Decker, Fortunes and Failures: White-Collar Mobility in 19th Century San Francisco (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1978) and Gray Brechin, Imperial San Francisco: Urban Power, Earthly Ruin (Berkeley: University of California Press), who argue for the dominance of the big bourgeoisie. The fine social history by William Issel and Robert Cherny, San Francisco, 1865–1932: Politics, Power, and Urban Development (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986) stands somewhere in the middle.

EVERYONE AGREES, HOWEVER, that the city has been politically progressive (liberal to left) during most of the postwar era. This is well documented in Richard DeLeon, Left Coast City: Progressive Politics in San Francisco, 1975–1991 (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1992), and backed up by John Jacobs, A Rage for Justice: The Passion and Politics of Phillip Burton (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995). The historical antecedents of this political tilt are presented by Philip Ethington, The Public City: The Political Construction of Urban Life in San Francisco, 1850–1900 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994), and Bill Issel, “Business Power and Political Culture in San Francisco, 1900–1940,” Journal of Urban History (1989) 16(1), pp. 52–77 and “New Deal and Wartime Origins of Postwar Urban Economic Policy: The San Francisco Case” (unpublished manuscript, Department of History, San Francisco State University, 1995). This is corroborated by Roger Lotchin, “World War II and Urban California: City Planning and the Transformation Hypothesis,” Pacific Historical Review (1993) 62/2: pp. 143–71.

ONE FOUNDATION FOR THIS LIBERALITY is undoubtedly the strong labor movement of the past, which is well treated by McWilliams but in more detail by Issel and Cherny, and Michael Kazin, “The Great Exception Revisited: Organized Labor and Politics in San Francisco and Los Angeles, 1870–1940,” Pacific Historical Review (1986) 55: pp. xxxx, and Barons of Labor: The San Francisco Building Trades and Union Power in the Progressive Era (Urbana & Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1987), and David Selvin, A Terrible Anger: The 1934 Waterfront and General Strikes in San Francisco (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1996). Kazin and Selvin understand the curious class makeup and outlook of San Francisco workers, who were mostly skilled and highly independent.

ANOTHER WELL-REHEARSED THEME is the cosmopolitan character of the city, and its freewheeling, tolerant, and even libertine ways of life. See, for example, Herbert Asbury, The Barbary Coast: An Informal History of the San Francisco Underworld (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1933), John Findlay, People of Chance: Gambling in American Society from Jamestown to Las Vegas (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), Paul Groth, Living Downtown, Irena Narell, Our City: The Jews of San Francisco (San Diego: Howell-North Books, 1981), and Glenna Matthews, “Forging a Cosmopolitan Civic Culture: the Regional Consciousness of San Francisco and Northern California,” in Michael Steiner and David Wrobel, eds., Many Wests: Essays in Regional Consciousness (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, in press).

SAN FRANCISCO HAS A LONG BOHEMIAN TRADITION of wayward intellectuals and iconoclastic artists going back to the Gold Rush. This is surveyed by Frances Walker, San Francisco’s Literary Frontier (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1939), Oscar Lewis, Bay Window Bohemia: An Account of the Brilliant Artistic World of Gaslit San Francisco (Garden City, NJ: Doubleday, 1956), and Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Nancy Peters, Literary San Francisco: A Pictorial History from its Beginnings to the Present Day (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1980). The intellectual counterculture stole the national spotlight with the coming of the beats in the 1950s. On that era, see Jerry Kamstra, Stand Naked and Cool Them: North Beach and the Bohemian Dream, 1950–1980 (San Francisco: Peeramid Press, 1981), Michael Davidson, The San Francisco Renaissance: Poetics and Community at Mid-Century (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989), Rebecca Solnit, Secret Exhibitions: Six California Artists of the Cold War Era (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1991), Richard Candida Smith, Utopia and Dissent: Art, Poetry and Politics in California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), and Linda Hamalian, A Life of Kenneth Rexroth (New York: W. W. Norton, 1991).

BY THE END OF THE BEAT ERA, the counterculture had become a mass movement, led by hippies, as described by Sherri Cavan, Hippies of the Haight (St Louis: New Critics Press, 1972), and Charles Perry, The Haight-Ashbury: A History (New York: Random House, 1984), and was joined by the political high tide of the civil rights movement, student rebellion, antiwar actions, and the rest of the sixties. The latter history has not been adequately told for the Bay Area, but see Max Heirich, The Spiral of Conflict: Berkeley, 1964 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1971), Gene Marine, The Black Panthers (New York: Signet Books, 1969), and Albert Fortunate Eagle, Alcatraz, Alcatraz: The Indian Occupation of 1969–71 (Berkeley: Heyday Books, 1992). The best treatment of the sixties in the Bay Area is by an Australian, Anthony Ashbolt, in Tear Down the Walls: Sixties Radicalism and the Politics of Space in the San Francisco Bay Area (doctoral dissertation, Australian National University, 1989).

ON THE GAY REVOLUTION, see Allan Bérubé, Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War Two (New York: The Free Press, 1990), Manuel Castells and Karen Murphy, “Cultural Identity and Urban Structure: The Spatial Organization of San Francisco’s Gay Community,” Urban Affairs Review (1982) 22: pp. 237–59, Randy Shilts, The Mayor of Castro Street: The Life and Times of Harvey Milk (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1982), Mike Weiss, Double Play: The San Francisco City Hall Killings (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1982), and Susan Stryker and Jim Van Buskirk, Gay by the Bay: A History of Queer Culture in the San Francisco Bay Area (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1996).

ONE HAS TO BE CAREFUL not to romanticize a social order that was accompanied by vicious racism. On this see Alexander Saxton, The Indispensable Enemy: Labor and the Anti-Chinese Movement in California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971), Susan Craddock, “Sewers and Scapegoats: Spatial Metaphors of Smallpox in Nineteenth Century San Francisco,” Social Science and Medicine (1995) 41/7: pp. 957–68, Albert Broussard, Black San Francisco: The Struggle for Racial Equality in the West, 1900–1954 (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1993), and Kazin, Barons of Labor. The civil rights movement was relatively strong in the Bay Area; however, there is little documentation on this.

This article is excerpted from "Appetite for the City," originally published in Reclaiming San Francisco: History Politics Culture, a City Lights anthology edited by James Brook, Chris Carlsson, & Nancy J. Peters (City Lights Books, San Francisco: 1998)