Naming of Haight Street, Part 2: The Maps

Historical Essay

by Angus MacFarlane

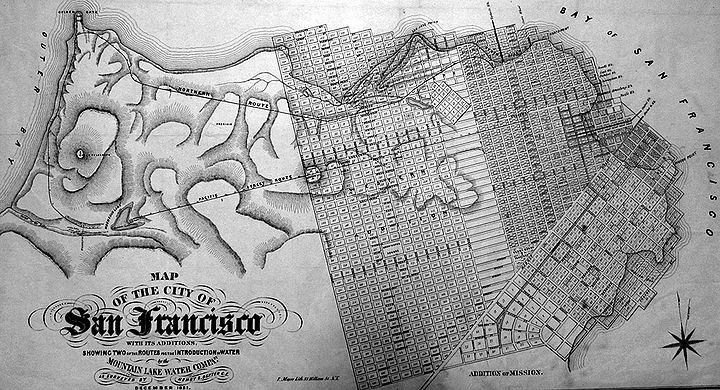

In January, 1852, Henry W. Haight’s bank, Page, Bacon & Co., was selling bonds to raise $800,000 to build a water delivery system from Mountain Lake at the Presidio to San Francisco. (26) On March 31, 1851 the city council had granted Azro Merrifield permission to begin the project. To help potential investors understand the scale of this undertaking, a 3’ x 4’ map adorned the PB&Co. office showing two pipeline routes that were under consideration. The map was not overly large in its dimensions, but the area of San Francisco that it detailed was unprecedented. Just two years after the publication of William Eddy’s “official” 1849 map of San Francisco, this map charted the greatest cartographic leap westward in San Francisco history.

The western boundary of Eddy’s 1849 survey was Larkin Street. The map at PB&Co., surveyed by Henry Dexter and published in December 1851, stretched as far west as the outlet of Lobos Creek in the Presidio (the equivalent of today’s 25th Avenue) and as far south as the east-west line of today’s Kirkham Street and 17th Street. Terrain features were shown as far south as the line of O’Farrell-Anza Streets and east to approximately Gough Street.

The map’s most riveting feature, however, was a block-by-block survey that pushed the western edge of San Francisco a whopping 1.5 miles beyond Larkin Street. This westward surge was greater than the distance from Larkin Street to the city’s eastern boundary at the waterfront.

The City Charter of 1850 formally established San Francisco’s Charter Line, i.e. its legal city limits. The western Charter Line of 1850 was near today’s Webster Street. The Charter of 1851 moved the line to near today’s Divisadero Street. (27). Dexter’s 1851 map, which also included Eddy’s east of Larkin survey, defined blocks as far west as nearly to today’s Central Avenue, an additional quarter mile beyond the 1851 Charter Line. But it had nothing to do with the legislative acts of 1850 and 1851. This map, portraying an ordinary grid of 17 north/south streets and 49 east/west streets that defined over 600 blocks west of Larkin Street, was purely unofficial.

Official or not, the new streets needed names. North of McAllister Street to the bay, Dexter’s map kept the same street names for the east/west streets as Eddy’s survey, merely extending them westward from Larkin Street to the edge of the surveyed portion of the map. But 17 newly surveyed north/south streets between Larkin and the western-most street needed names, as did 13 east/west streets in the area west of Larkin, south of McAllister Street and north of Market Street. The names of these 30 new streets comprised a who’s-who of now-forgotten yet once-prominent San Franciscans of the pre- statehood era.

The west-of-Larkin area shown in Dexter’s map covered over three square miles, the 66 streets were over 100 miles long and there were over 600 separate blocks. If Dexter’s intent was to show the pipeline routes, (one running east along Pacific Street to Broadway and Mason, and the other going circuitously around Fort Point and then east to Chestnut and Hyde) why did his survey extend more than 1.5 miles south of Pacific Street to Grand Street, the southern-most street on this west-of-Larkin survey? It seems like a lot of unnecessary work.

Dexter’s map was surveyed for Azro Merrifield’s Mountain Lake Water Company and was published in December 1851, but there is overwhelming evidence that there was an earlier map of the territory west of Larkin Street which was the template for Dexter’s map.

The Alta announced a real estate auction for November 11, 1850, listing 195 lots on 32 blocks in an area bounded by Larkin Street on the east, Union Street on the south, the bay on the north and a street named Division west of Larkin. Other west-of-Larkin streets listed in the advertisement were Sparks, Marlette and Webster. A note at the bottom of the ad read: “Titles indisputable being the property of Hervey Sparks.” Hervey Sparks was a self-described real estate dealer whom historian H. H. Bancroft also refers to as a real estate dealer as well as a banker.

A second auction in what was called “Western Addition” was held on June 7, 1851. Much larger than the November 1850 auction of Hervey Sparks’ property, this one offered 426 lots on 94 blocks in the area bounded by Division on the east, Lombard on the north, Hays [sic] on the south and “the western boundary” which was Cannon Street on Dexter’s map. Oddly, 20 streets listed in the two auctions corresponded to streets on Dexter’s not-yet published map of December, 1851. Additionally, Dexter’s map not only shows streets named in the earlier auctions, but it also shows the exact block numbers from the June 7, 1851 auction which preceded the map’s publication by six months.

Which raises the questions: Did Dexter conduct a completely separate survey of the entire west of Larkin area for the Mountain Lake Water Company in the brief time between receiving permission on March 31, 1850 and publication in December? Or did he simply superimpose the water company’s two pipeline routes on an existing map?

The only logical explanation is that he superimposed the pipeline routes onto an existing map—a template map. There is clear-cut evidence of such a map according to a report in the Alta of December 25, 1850:

MAP OF SAN FRANCISCO—We have received from S.H. Marlette a complete map of San Francisco compiled from the original surveys of W.M. Eddy [and] the western addition as surveyed by S.H. Marlette, civil engineer. (Italics added.)

The Daily Courier printed a similar acknowledgment of receiving Marlette’s map on Christmas Day.

Unfortunately the map no longer exists, but it is mentioned in Marlette’s biography.

Senecca H. Marlette was born near Syracuse, New York on January 18, 1824. He arrived in San Francisco September 4, 1849. He went to the mines of Calaveras County, but upon returning to San Francisco for provisions, he obtained a position with the city as a surveyor. He surveyed the city at $20 per day, but had to pay $3.00 for use of a compass. Later he bought instruments for surveying, including a theodolite, going in debt for them and paying 6% interest per month.

For [Henry W.] Halleck, [Archibald] Peachy, [Frederick] Billings and [Dexter R.] Wright he made a survey of a part of the Larkin Grant, now the western addition, to San Francisco, surveying blocks and lots. (Italics added.) He then surveyed a sub-division between this and the city for Hervey Sparks.

Later Mr. Marlette made arrangements for the publication of a map of San

Francisco, including the Western Addition (28). (Italics added.)

Further evidence of Marlette’s 1850 Western Addition survey comes from assurances to prospective bidders at an auction in February 1853 in the same area as the auction of November, 1850.

This property is situated in the Western Addition to the city as surveyed and laid out in lots by J. [sic] H. Marlette, Esq. in April 1849 as formerly owned by Hervey Sparks, Esq., under whose direction it was surveyed and improved. (29)

A lost piece of San Francisco’s past is the history of the Western Addition and the roles of Thomas Larkin, Archibald Peachy, Frederick Billings and others. A notice in the San Francisco Herald accompanying the announcement of the large auction of Western Addition lots on June 7, 1851 provides a starting point for the chronology of ownership of the west of Larkin land.

A large sale of real estate comes off today at the sales rooms of Wainwright, Byrne & Co. The property to be sold is at present owned by Messrs. Peachy and Billings and is part of the Rancho de los Lobos, granted June 26, 1846 to Benito Diaz by Gov. Pio Pico and transferred by Benito Diaz and wife on September 16 to Thomas O. Larkin of Monterey. By T. O. Larkin and wife it was transferred to Dexter Wright on September 16, 1849, and from Wright it came into the ownership of the present possessors. (30)

In June 1846 California was still a part of Mexico and Pio Pico was the last Mexican governor. Pico granted Benito Diaz, the custom house officer in Yerba Buena, two leagues of land—about 14 square miles—which became known as Rancho Punta de los Lobos or Rancho de los Lobos. It was bounded on the north and west by the golden gate and the ocean; on the south by the line of today’s Noriega Street and 21st Street; and on the east by the line of Gough and Valencia Streets.

Diaz sold the rancho to Thomas Larkin for $1,000 in September, 1846 and it became known as Larkin’s Grant. The next documented owners were Dexter R. Wright and his brother-in-law Bethuel Phelps who paid Larkin $50,000 for it in 1849. It’s not recorded when Archibald Peachy and Frederick Billings became owners of the Western Addition portion of the much larger Rancho/Grant. (31)

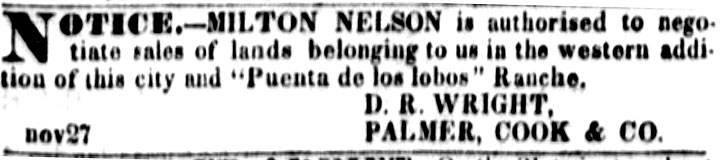

From November 26, 1850 through January 1, 1851, Dexter Wright printed notices of his intent to sell the land.

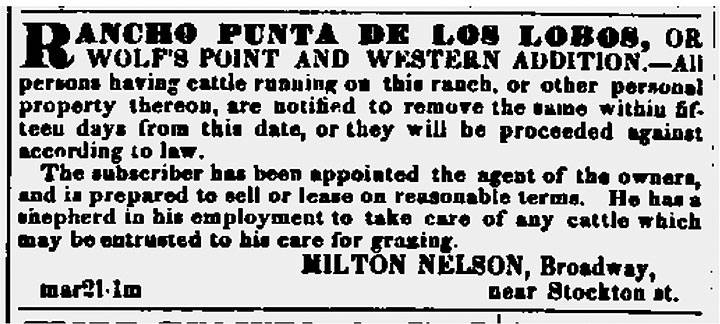

From March 23, 1851 through April 26, the following notice appeared in the papers.

On June 7, 1851 the big auction of Western Addition property was held

At the time of Marlette’s survey (approximately late-1849 to mid-1850), Peachy and Billings was a law firm specializing in land cases in post-Gold Rush California. (Halleck would join the firm on December 31, 1849.) Seven streets on Dexter’s map are named for men closely associated with the west of Larkin territory: Sparks, Marlette, Peachy, Billings, Halleck, Wright and Phelps.

Additionally, Azro Merrifield of the Mountain Lake Water Company has a street named after him.

As mentioned above, 20 of the 30 newly named west-of-Larkin streets on Dexter’s map north of today’s Hayes Street to the bay and west of Larkin Street to nearly Central Avenue are named in auctions held 6 and 13 months before the map’s publication. Ten east-west streets south of Hayes Street (or Hays on the Dexter map) are not mentioned in either advertisement, yet have names as well as block numbers on Dexter’s map. One of these streets, running east-west between Graham to its north and Middleton to its south, is labeled Haight Street.

The prevailing Haight Street myth holds that it was named after banker Henry W. Haight. Is it really conceivable that Henry Welles Haight, after being a San Franciscan for a mere 18 months, had ascended to the civic pantheon of having a street named in his honor on Dexter’s December 1851 map?

Or could it have been named for his nephew, Henry Huntley Haight, who had been practicing law in San Francisco for less than two years?

Or could it be named after Samuel W. Haight, who had been in San Francisco since 1847 and had hobnobbed with the city’s leading citizens over the previous four years in his civic, social, political, and business dealings. This would include the owners of the West of Larkin Street territory such as Thomas Larkin and Archibald Peachy.

If Marlette’s 1850 map had in fact been the template for Dexter’s map of a year later, then the window for eligibility to have Haight Street named in honor of one of the Henrys would have been reduced by one year. Even assuming that the street names were chosen after Marlette had completed his survey, the printing process would have necessitated that the final product, including street names, be at the printer well before the Christmas Day 1850 announcements in the city’s newspapers.

Under these time constraints (less than a year for attorney Henry H. and less than six months for banker Henry W.) the Henrys simply would not have been in San Francisco long enough to stand alongside the pre-statehood notables who had been making reputations for themselves for years before the Henrys arrived.

This leaves Samuel Welles Haight as the only candidate deserving of having Haight Street named in his honor on Marlette’s map in 1850 and subsequently copied, along with dozens of other streets, onto Dexter’s 1851 map.

Notes:

26. Daily Alta California, January 24, 1852, page 2, column 1; The Mountain Lake Water Company.

27. Daily Alta California, April 16, 1850 page 2, column 5;—AN ACT TO INCORPORATE THE CITY OF SAN FRANCISCO, Passed April 12, 1850. BOUNDARIES: Section 1: The boundaries of the city of San Francisco shall be as follows: The . . . western boundary shall be a line one mile and a half distant from the center of Portsmouth Square and which line shall be parallel to the street known as Kearny Street. And Daily Alta California March 23, 1851 page 2 column 1; LEGISLATIVE DOCUMENTS--CHARTER OF 1851: The western boundary to be a line two miles distant from Kearny Street.

28. Guinn, J.M., A History of California and an Extended History of its Southern Coast Counties; Also Containing Biographies of Well-Known Citizens of the Past and Present. vol. II, Historic Record Company, Los Angeles, Cal. 1907, page 1213.

29. The discrepancy between Marlette’s date of arrival in San Francisco and when he conducted his survey doesn’t change the fact that he did indeed conduct a survey and subsequently published a map of his survey.

30. https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/65/125 RE: Joseph C. Palmer, Charles W. Cook, Bethuel Phelps and Dexter R. Wright, Appellants, vs. The United States.

31. Daily Alta California, December 5, 1857 page 2, column 2: The Rejection of the Benito Diaz Claim.

Continue reading Naming of Haight Street part 3 / Back to Part 1 of Naming of Haight Street