The Big Q

"I was there..."

by John Krich

I guess the Sixties stopped when we stopped going to see the prisoners. We stopped because we didn't want to be "bleeding hearts" any longer, or because we'd decided that wasn't our real constituency, or because we just couldn't stomach it any longer, or because we felt like we'd seen every last one of them. We couldn't stop looking at the places where we lived, so we fought things out right there. We couldn't stop breathing or eating, so we went to the trouble of improving what we ate and breathed. Some people were obstinate enough to claim they couldn't stop thinking, so they set about improving the quality of what they were allowed to think. A few zealots for the human race went so far as to insist they couldn't stop making babies, so they devised new and improved ways to get that job done. But if we watched our televisions with selectivity, and chose our company with consummate care, we could avoid looking at those damn jails, and the men in them. We did things in our own self-interest now, we told ourselves, and that was a much less abstract basis for doing things than any basis we'd had in the past. More liberated. Expunged of guilt. But it never really seemed in my "self-interest" to forget about the prisoners, and to forget the system's singular threat that kept men sitting, and stewing, and unseen.

San Quentin gate.

I remember the last time I went to see the prisoners. Trials were being held inside the gates of San Quentin, for the sake of the state's security—poor, insecure state—but a limited audience had to be admitted so the trials could be called public. Yesterday's revolutionaries had become today's persecuted captives. The last power left to their followers was the power to witness. It usually began with the romance of waking much earlier than I was accustomed, maybe even waking when the prisoners did, followed by the conspiratorial exhilaration of walking across a sleeping city, an Oakland untrafficked, to the car pools' assembly point. I replaced sleep with self-righteousness: if I could not rouse myself to do this, who would? Who would come see about that other city, that other Oakland? Yet each week the trials stumbled on, the number of drivers dwindled. There were too few cars and some of us had to be left behind to face a long day in the city. A rule of the movement: a hundred promises, a dozen drivers. And most of them late, too. It seemed that people were coming to fear the future to which they'd committed themselves as they might fear an appointment with the dentist.

But I got my ride that morning, and it was such a good ride, I sensed it would be my last. I rode in a beat-up Volvo wagon, with stacks of undistributed leaflets hogging the cargo space. Several large mutts shared the car with me also, as did a comforting assortment of fretful fellow travelers. These were the hardy ones, the ones who always looked more fretful, more fellowed, more traveled, than me. On past trips, songs had been sung. Everyone knew the same ones—"Bandiera Rosso," or "Joe Hill," or "The Revolution Is For The Young," with its inexplicable second line, "That's why we dig Kim II Sung ..." But this last time, the male voices were silent. This was a recent development, and though it may have broadened the range of the people's chorus, it made for an atmosphere of surliness, or morning grump, among the new minority. The women rode in front, and sallied forth about Ken-Po karate or cosmic massage or the beneficial effects of the canteloupe.

Missing, too, was the brisk competence of the street medic, with his memorized spiel about all the possible horrors we might encounter, all the lethal gases to which we might expose ourselves. That final morning, there was none of the suspense of martyrdom. You kept your peace inside the Big Q—if you had any peace to keep—unless you were prepared for more trouble than any medic could brief you on.

The mood in the Volvo modulated when we came to the long bridge at whose end was our inconvenient destination. On all sides of us, sublime blue. Furry tips of islands, too small to have been built upon or over, sat like green commas in the bay's broad flow. The surrounding hills were the foreheads of drowned men. Flat .tankers passed under the silver bridge, its span self-cleaning as a cat. Mostly, the eyes stayed with the little islands. It was always this way when I was going to see the prisoners.

I always noticed how clean San Quentin looked, stationed on its sea promontory, as though the waters washed up to lick the sandy walls and the khaki guard towers. There were so few windows in the place. It was corny, but I wanted the prisoners, political or otherwise, to see the still and perfect light of that morning. What a prized view there must have been from the fluted trunks of the main tank! If only the bay beyond was not another barrier, an accomplice of the Big Q!

San Quentin Prison, exterior walls.

Photo via Flickr user Andrew Reid Wildman, Artist, Writer, Photographer

We parked at the far end of the gravel driveway, though we knew our license plate number would be recorded anyway. We reconnoitered with our fellow witnesses in front of the main gate. After all, the authorities had to get nice, sharp photographs of all of us, too-assuming they didn't have them already. We allowed ourselves to be seen, but the last glimpse was on them. While the F.B.I. agents saw us, we saw one another, saw that we were not the only ones left, that we were alone together. There was no singing at the gate.

A line had already formed. We had to wait to be admitted before we could be an audience. We had to wait to be disorderly by being quite orderly. A revolution, we were learning, involved waiting.

The Assistant Warden was greeted with swallowed hisses. He was just another regular on our morning shift. He reminded us of the guidelines our conduct had to follow once we got inside—a speech he gave each day of the trials. Not even sunglasses and a hedgehog cut, inky continental suit, could disguise the porcine nature of the Assistant Warden. That equation of pigs and police may have been a tactical error, but in poetic terms it was right, too right. The line tried to look away from this archetypal jailer as he spoke, hoping he would somehow disappear. We gazed instead into the windows of the prison gift shop against which we were queued. There were trinkets and handicrafts on display, but the paintings were most striking. The colors were predictably dampened, the brushwork unexpectedly skilled. From the blackness of the cell, subtly unlike the cheesy black backdrop of the carnival artist, portraits of Martin Luther King and Malcolm X emerged like bruised heavyweights set for another comeback.

The Warden's boys led us through a narrow guardhouse, frisking us one at a time, then loaded the line onto a golf cart that took us to the main compound. Again, the bay beyond was poignantly pretty. Quiet beaches once graced this point, now capped with its asphalt scum-bag held tight with barbed wire. Pistol-laden officers herded us into a makeshift courtroom, just four rows of collapsible wooden seats, several tables, and a podium. This hall had recently been used for the prisoners' recreation. I could almost hear a ping-pong ball echoing in it, but the echo was faint compared with the bailiff clearing his throat, stenographers scratching their pads, lawyers clicking their attache cases, a judge rustling his robes. There was no way this penitentiary mock-up could be made to look like a set for Perry Mason. Rising for the stem judge, we already felt we'd made our point—at least to ourselves. This kind of justice had something to hide.

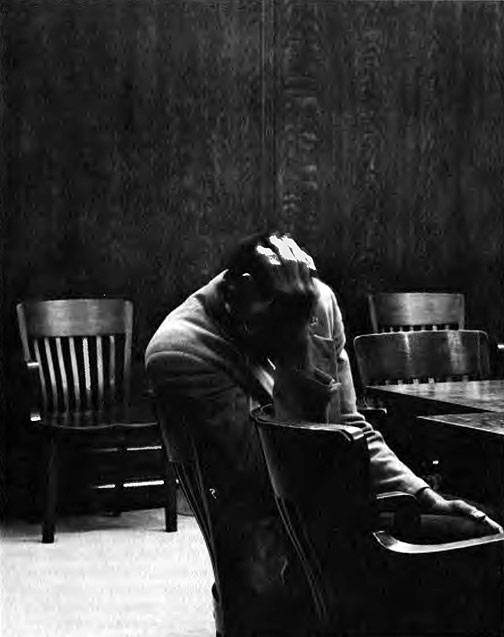

Then, at last, our prisoner-for-a-day. That last morning, my last outing, we were all very lucky, if you could use the word lucky inside the Big Q. The plaintiff was a famous man, bordering on the infamous. He was a "movement name," who still carried with him the wounds of an heroic deed. But he was such a small man, almost a miniature, being carried in by two immense guards. His bandages, wrapped haphazardly around his middle under a faded prison shirt, were hardly distinguishable from the thick link chains which bound his arms to the guards and to one another. Unable to walk, constricted by steel and laws, this man was still dangerous. A fire had entered the room, and the audience rose to warm itself. We shook our fists. The little prisoner, his chest heaving and swollen with encumbrances, raised his arm in reply, and I could not see how he was able to do it.

On Trial.

Photo: Dorothea Lange

The prisoner crumpled in his seat, but the two guards continued to hover over him. Lawyers cleared their throats and presented motions and admitted the prisoner did not want their representation. "May I speak?" The prisoner startled the proceedings with his powerful voice. Startled his admirers, too. His tormentors poked and shoved him. The judge went on, having heard nothing. "Let him speak!" someone called from the back row. Guards flinched, then moved toward the sound. The judge pounded a dimestore gavel. "There will be no further disturbances in my courtroom!" But what made it his courtroom? The gavel? The steno girls? The guns? Excuse me, your honor, but this is a prison, the pokey, the can, and it's quite clear that once you get a certain sort of man in here, you have no intention of ever letting him get out. The trial must legally have its audience, though, and we could delay this trial by forcing the guards to clear us, then seat us, over and over again. But the word has come down that the prisoner wants no delays. Besides, we were all poor spoiled children who'd awakened so early and come such a long way to see this show. We wished to continue watching what we hoped to stop as much as they wished to stop us from watching.

There were pleas, counter-pleas, swift denials from the judge, deliberations that granted only delay on delay. Then it was finished. They needed more time to figure out how to handle a man who not only refused to be found guilty, but refused to be judged. The prisoner was carried out and we stood for him again. He had been worth the price of admission. He smiled wickedly through a wince of pain. He must have appreciated our gesture in a way that we could never appreciate his. At the back door, he screamed toward the judge, "Nazi!" No hysteria in his delivery. No whine. "I won't be tried in no Nazi court! You can't lynch me so easy!" No doubt the guards jostled the prisoner's wounds as punishment for his outburst, but they waited to do so until they were out of view. That was our lack-we could only be witnesses in one place, at one time.

The prisoner, too, had shown his weakness. For all his courage, he had chosen the wrong epithet to hurl. There was no doubt the judge ran an operation by which the most free black men lost their freedom for good, but if the man behind the podium was a Nazi, there had been something very wrong with all those World War Two movies. And this wasn't a movie. This was the Big Q. You couldn't afford to be inaccurate here. It was important to know just the right word, especially if that word was the last one you could speak before being gagged. The Nazi equation made us doubt ourselves. It was like all that talk about how "we were all prisoners." That was what finally kept us away. It made for a generous scale of relativity that just lulled people. If we were all prisoners of this system or that, then we were all equally miserable. And since many of us were actually not very miserable at all, it followed that those of us in prison weren't so bad off either. We were all in the same cage, weren't we? We could know ,all we needed to know without leaving our living rooms, couldn’t we? We didn't have to see those specific, identifiable prisoners anymore, did we?

That last morning, on my last vigil, my final stand outside the gates of San Quentin, the talk about "fascism" went on. If you believed the Black Panthers at the rally down by the water, by the bay gently lapping, if you believed all the speakers at all the rallies in those days, then things couldn't have gotten much worse. We'd already hit bottom in America, they ranted, but in fact we weren't really at the bottom at all. That was just like the non-verbal Sixties: nobody knew how important it was to get the words right. A revolution meant lifting the veil of things as they were, and we needed words to lift veils, too. We couldn't just throw down a blanket of rhetoric and smooth it out. It was like a proof—there had to be intermediary words, just as there were intermediary steps. If the words were correct, if the equation was balanced, there would be action. Action would transform our need for the old words and help create new ones. If the words were wrong, If wrong from the start, then they remained leaden, just a collection of syllables. Like the slogans with which those leather-jacketed dialecticians bullied us as we sat crosslegged in the prison's gravel driveway. Once, this had felt like leadership. Now, there was only beratement. Those stern black faces, blacker against the calm waters at their backs, could offer only one grand strategy. After all the demonstrations occupations, confrontations, they now asked for the ultimate exemplary act. They were no longer satisfied with a sacrifice of the spirit; they demanded a sacrifice of the flesh.

It wasn't that dying for a cause was such a bad idea. I mean there wasn't a rightness or a wrongness to it. And sometime after some of what you saw, you were willing, you were ready for it. But it was like the words—you had to feel it was leading to something else, that you didn't want to do it just to feel good. Or feel nothing. The crowd chafed at the Panthers' call for blood, and moved away. And I moved away with it. Leaving the ghetto fighters eulogizing themselves, leaving them at the shore of the bay whose erosions seemed so futile against the Big Q's fortifications, leaving them two hundred yards from the gas chamber—in which a lot of cats had passed, had taken their place in the galaxy—it wasn't clear who was leaving who behind. But I remember those men spoke like they were the first ones to come up with their solution, like they'd dreamed it out of nowhere, as if they'd just invented the notion of an honorable death.

Originally “Captain Sal and the Age of Irony,” a Chapter in Bump City by John Krich (City Miner Books, Berkeley CA: 1979)