Black Nationalism in Oakland

Historical Essay

by Sybil Lewis, 2015, Part 1 of 3

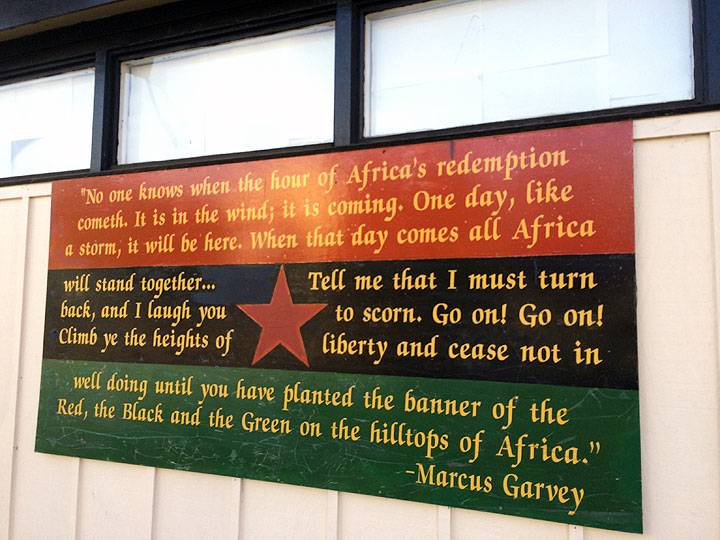

Uhuru House in East Oakland

Photo: Sybil Lewis

| Black nationalism, the conception of an autonomous Black nation where people of African descent can organize around shared experiences of oppression to form representative economic, political, and social structures to govern their lives, has strong roots in Oakland that precede and follow the Black Panther Party. Black nationalist organizing in Oakland has continued to this day through two organizations, the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement and the African People’s Socialist Party. |

Since the Black Panther Party caught the eye of the nation in 1966, popular culture has conceived the Black Panthers and Malcolm X as the birth and death of Black nationalism and the Black liberation movement. As the repression of the Black community in Oakland has continued, so have traditions of resistance. The recent Black Lives Matter movement against police brutality in Black communities elucidates how many of the conditions that the Black Panthers were fighting have persisted. Two organizations in particular, the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement and the African People’s Socialist Party, have carried forward Black nationalist organizing in Oakland.

Historical Roots of Black Nationalism

Black scholars identify a spectrum of tendencies within the Black freedom struggle, ranging from integrationist to nationalist strategies. The history of integrationist tactics is well documented through the legacies of Martin Luther King Jr. and the legislative work of the NAACP. The roots of nationalist demands for Black independence can be traced back to the 19th century. Inherent in Black nationalism is the conception of an autonomous Black nation where people of African descent can organize around shared experiences of oppression to form representative economic, political, and social structures to govern their lives. The colonization movement, laying the foundations of the modern Back-to-Africa movement, argued for Black emigration from the U.S. to Africa and Latin America on the assumption that political independence and freedom was unattainable as long as Black people lived as minorities.(1) The Black abolitionist, arguably the grandfather of Black nationalism, Martin Delaney argued in 1852 that self-determination of Black people depended on forming a separate Black Nation outside the U.S. In 1918, Marcus Garvey, the Jamaican political figure, created the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) proclaiming the need for economic and political self-determination, and also appealed to notions of a shared identity among the African diaspora, that Black was not a race but a nation.(2) Garvey’s philosophy had a lasting impact on the Black power movement. Malcolm X was attracted to the Nation of Islam in the late 1940s due to “the organization’s adaptation of Garvey’s socio-political philosophy of Black nationalism, emphasizing group empowerment through cultural pride, economic development and social separation,” and went on to take the analysis further by identifying the U.S. as a colonial state and connecting Black oppression in the U.S. to colonial struggles in continental Africa.(3)

The Black Panther Party, The Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, and the African People’s Socialist Party

The Black Panther Party (BPP) formed in Oakland in 1966 by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale with an understanding of Black people in the U.S. as colonial subjects under an oppressive, alien state, wherein the road to freedom required a fight for economic and political self-determination. They had several different projects ranging from community projects to meet the immediate material demands of the community to self-defense training to cultivate military power against, and ultimately to overthrow, the U.S. government.

The worldwide attention given to the BPP inspired both the formation of more Black nationalist groups and efforts by the U.S. government to repress their operations, namely through the covert FBI program called COINTELPRO. It is within this contradictory climate of inspiration and repression that The Malcolm X Grassroots Movement (MXGM) and the African People’s Socialist Party (APSP) — for both of whom a Pan-African ideology underscores perceptions of identity and nation — were formed as national mass organizing bodies with chapters across the country, including in Oakland.

Organizers from both organizations stress the importance of multi-generational work and also offer workshops and training programs for black adults to learn about the foundations and understandings of black history. For instance, the MXGM offers community workshops led by organization members on issues such as police brutality, political imprisonment, and gender and the APSP regularly offers full weekend politicization courses on the historical analysis and organizing strategy of the party.

Inscriptions on the wall at the Uhuru House show Marcus Garvey’s influence.

Photo: Sybil Lewis

MXGM

The national organization of the MXGM was founded in Brooklyn, New York in 1993 as the mass organizing arm of its predecessor organization, the Provisional Government of the Republic of New Afrika (PGRNA), to organize campaigns that address the material conditions of Black people in order to build capacity to create the Republic of New Afrika, a five state Black nation in the South. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s in Oakland and other parts of the Bay, the PGRNA was conducting educational campaigns and school programs to familiarize black people on the ideals of the Republic of New Afrika. In Oakland, founding members such as Maya Ayanna Mashama, were affiliated with the PGRNA and had extensive experience with other Black organizing projects, including the Black August Organizing Committee for prison inmates and political exiles. “We thought it was a great idea to create a MXGM chapter in Oakland because of the strong Black nationalist revolutionary history in the Bay Area,” Mama Ayanna noted about the 1993 formation.(4)

APSP

The APSP was founded in St Petersburg, Florida by Omali Yeshitela in 1972 with the goal of leading the African working class into a revolution against the U.S government to

seize state power. The APSP is the membership-based political party representing the Uhuru Movement, which means freedom in Swahili. The International People’s Democratic Uhuru Movement (InPDUM) that serves as the mass organization for the APSP that is open to everyone and primarily does economic work for the party. The influence of the BPP was significant to the foundation of the APSP and is why the chapter headquarters was located in Oakland from 1981 to the early 1990s, during which time they led economic enterprises, rallied against police brutality, and created health clinics. The Oakland office transitioned to a regional office after the headquarters moved back to St Petersburg in the 1990s.

Organizing and Repression

While the Panthers harnessed a momentum around Black nationalism, organizers on the ground cite that the period was also marked by an attack on Black radicals and an overall dismantling of a strong Black community base. The BPP’s strategic use of the media to advance its goals and the public displays of defiance—most notably the BPP’s 1967 protest carrying large rifles at the State Capitol in building in Sacramento—made the party one of the primary targets of COINTELPRO, a U.S. government counter-intelligence program to control political dissent. According to FBI documents, one of the strategies of the program was to "expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize the activities of the Black nationalists".(5) Officially COINTELPRO lasted between 1956 and 1971, but activists in Oakland contend that the program and its effects continued into the 1980s.

Mama Ayanna details her experience with COINTELPRO and state repression in the late 1970s and early 1980s in Oakland:

From the beginning if you were any kind of Black revolutionary or part of a Black Nationalist organization that had values and ideals about self defense and self determination then you were consistently under attack. All of us who were part of the Black August Organizing Committee were under surveillance and were constantly harasses and arrested with any number of crimes that were obvious frame-ups since almost all were acquitted. My husband at the time and sister were put on trial, people disappeared and ended up dead on the side of the road, and my home in South Berkeley was consistently raided.(6)

Urban development projects have historically reduced and dismantled the Black population in Oakland, [link to Jennifer’s entry], which is now half what it used to be in 1980.(7) Organizers in MXGM and APSP see this decline as a systematic attack on the Black community that makes mobilizing a mass Black population difficult. Mama Ayanna recalls in an interview:

Once upon a time in the 1960s and 1970s you would have found in the Bay Area an intact Black community running from the South Bay to Oakland as far as 106 Street in East Oakland. There was a thriving Black community with Black businesses, cultural centers, clubs—all of the things that you now just find sprinkled in Oakland. Because of Panthers and other people on the ground and on the streets educating the community you also had a strong support for organizing and resistance in black community. The attack on the Black community occurred in several ways and one of the most hurtful ways was removing the economic base of the community. You used to have a lot of strong Black families that were employed, but with the mass incarceration movement in the 1980s and the attack on Black organizers you do not see men in the streets anymore. Now the family[-owned] Black businesses and grocery stores have been replaced by liquor stores and many professional Black families with strong family and community values have been dismantled.(8)

Continue reading about MXGM and APSP in Imagining Nationhood and Self-Determination [FSF link part 2] and Responding to Police Brutality, Self-Defense, and Prison Organizing [FSF link part 3]

Notes

1. Smallwood, Andrew P. "Black Nationalism and Black Power." A Bibliography The Negro in

America (University of Nebraska Press; 1970).

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Interview with Mama Ayanna Mashama by author, May 15, 2015.

5. A Huey P. Newton Story, “COINTELPRO”, PBS (Luna Ray Films, 2002)

6. Interview with Mama Ayanna Mashama by author, May 15, 2015.

7. Kuruvila, Matthai, “25% drop in African American Population in Oakland” (SF Gate, March 2011)

8. Interview with Mama Ayanna Mashama by author, May 15, 2015.