Brief History of Bayview-Hunters Point

Historical Essay

by Will Roscoe, 1995

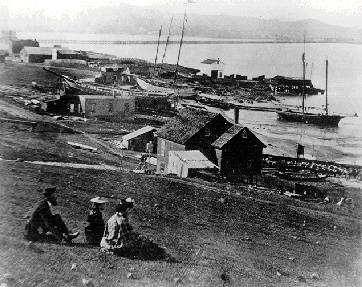

View northwest in 1866 across mouth of Islais Creek marshes with southern part of Long Bridge spanning its mouth.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, San Francisco, CA

Hunter's Point graving docks in the 1920s

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, San Francisco, CA

Originally Bayview was an Italian and Maltese enclave southwest of Third Street. Now it is 59% Black. Hunters Point was for many years the site of a Chinese shrimp fishing community. It was evicted in the late 1930's to make way for the WWII military build-up and the Hunters Point Navy Base.

In 1980, Bayview-Hunters Point was 77% Black, median age was 31 years, and median income was $16,846---well below the median for the city as a whole. Outwardly the area suffers from the typical problems associated with an inner city ghetto. But in three key areas the area does not conform to the stereotype of a ghetto.

Sixty percent of all homes are owner-occupied---almost twice as high as the rate citywide. There are numerous businesses and light industries in the area. The usual cycle of deterioration is not occurring. In fact, one study by Benjamin P. Bowser of Cal State Hayward, "Bayview-Hunters Point: San Francisco's Black Ghetto Revisited," found four distinct and diverse communities within the Hunters Point-Bayview area:

1) Hunters Point Housing Projects Since the mid-1960s, one set of projects has been torn down and replaced with middle income townhouses. The streets are named after the community leaders who fought for the development, all Black women. The remaining projects are even more isolated---the median age is 18.2 years and there are no recreation facilities in the projects; an entire area has been given over to drug dealing and largely abandoned by others.

Problems spill over to the surrounding areas, especially along the streets that link the projects to Third Street. There are visible characteristics of a neighborhood where public space is contested--shades down during the day, security bars on windows, garages always closed, sidewalks rarely swept, abandoned cars, residents rarely on the street.

The Double Rock Public Housing Project above Carroll Avenue in this 1996 photo.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

2) Old Bayview: South of the projects and east of Third Street. 84% Black, some blocks in decline, but owner-occupancy is high and other blocks are undergoing renovation. A low-rise, low-income housing project is on the eastern edge of this area, not as depressed at the Hunters Point projects. Many of the nearby residents are Black retirees who still control the public space.

File:Bayvwhp$bayview-mansion.jpg

A Bayview mansion, the Piper House (aka Sylvester House) at 1556 Revere Street, shown here in the 1990s. It was built in 1865 by Stephen L. Piper a well-known carpenter and house builder. Later, the Sylvester family, who were butchers and cattle dealers, lived in it from 1884 to 1900 during the period that Butchertown was located nearby. The house was moved to this location in 1913.

photo: Chris Carlsson

3) New Bayview: Area west of Third Street, has become predominantly Black since 1960, with little sign of downgrading. 72% owner-occupancy and the highest income levels and median age of the area. There's been a steady influx of Asians (Chinese and Filipinos) who are not put off by the reputation of the area for being a ghetto. The presence of Black middle-class areas so close to low-income housing projects is an exception to the general tendency for Blacks to leave Black neighborhoods as soon as their socioeconomic status improves. At the same time, despite their proximity to the Hunters Point projects, these middle class Blacks have little or no contact or involvement with other New Bayview residents.

One other unusual feature of the area as a supposed ghetto is the presence of many small industries and businesses in the adjoining warehouse area. The study also found that few of these businesses employed Blacks from the area. Those that had hired local Blacks reported high turnover. Other potential employers reported that they received few inquiries from neighborhood residents about jobs.

Conclusions

Although it is often claimed that the problem of the so-called underclass is that they lack middle-class role models, Bayview-Hunters Point has a visible Black middle-class, but there's no indication that its presence makes any difference in the lives of people living in the projects. The community leaders in the area tend to be ministers, small business owners, and leaders of community organizations. In the projects the activists tend to be older women, but none of them live in middle-class areas.

A key factor in perpetuating poverty in the area is its stigmatization as a ghetto despite its diversity. This stigma prevents investment, and discourages lower middle income homeowners from moving in and maintaining the housing stock. Because of poor and even worsening economic conditions for Blacks, there are few families able to enter the housing market and take advantage of the cheaper, older housing in the area.

1920s view of Bayview neighborhood.

Photo: Private Collection, San Francisco, CA