Shopping in the Bayview, 1920s

"I was there..."

By Ruth Eshow Upton

An Italian Shoemaker has his family home and shop at the edge of the Islais Creek swamp, c. 1900.

Photo: Greg Gaar Collection, San Francisco, CA

Islais Creek shoemaker's sign (detail), c. 1900.

The greatest difference in daily life probably was the way we shopped. Driving to a supermarket and loading a cart with provisions from foodstuffs to drugs was unimaginable. For one thing, the family car was used only on father’s day off for pleasure—social gatherings, picnics, trips out of town. Fathers took the street car to go to work and mothers didn’t know how to drive.

Most of what we consumed came directly to the house. Early every morning, while it was still dark, the milkman dropped off quart bottles of milk at the front door. He picked up the empties along with a handwritten note on a scrap of paper ordering butter or cottage cheese which he delivered the following morning. To combine the milk with the cream that had risen to the top of the bottle one gave it a vigorous shake. A small treat was licking the cardboard cap of the cream that had stuck to it. The milkman showed his face during the day only when he came to collect for the deliveries.

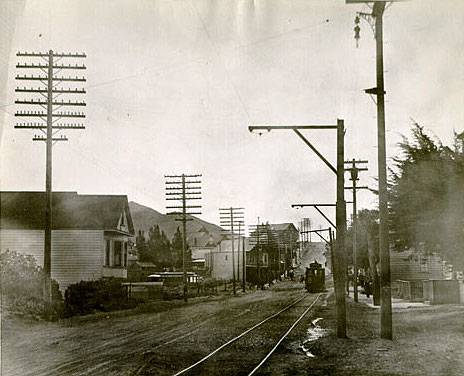

San Bruno Avenue and Silver Avenue, 1927.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Bread came from the Torino Bakery truck that stopped at houses on our street. My mother bought the loaves known as sourdough and milk bread; the latter was a small, crusty loaf with a cake-like inside. Wonder Bread trucks supplied the classic sliced white used for toast and for school lunches. Every so often the Hostess Bakery truck came by with its special treats—chocolate topped cupcakes and doughnuts; especially delicious were the powdered sugar sprinkled ones. All were perfectly fresh.

For meat and staples there was the classic corner store, Pantoleon Brothers, on San Bruno, not far from the Five Mile House. Being sent there with a list was no chore. I skipped all the way, anticipating the slice of baloney the butcher would give me after wrapping up the meat order, to which he often added free soup bones. Butchers shut down at 6PM so it was important to get to the shop well before that. Staples such as sugar, flour and the like were taken care of on the opposite side of the store.

The closest thing to a super-market was the Piggly Wiggly. It wasn’t more than a half mile from our house but San Bruno Avenue’s steep drop from our corner made it inconvenient for one carrying groceries. I don’t remember ever going there but the name stuck in my mind because of a joke I heard Mrs. Schmelter tell a group of ladies.. It involved a play on names of stores, the punch line being, “..and they piggly-wiggled in a safe way.” I had no idea what it meant but from the embarrassed titters I knew better than to ask. I filed it away with other mysterious words and phrases for the day when all would be revealed to me.

Eggs and chickens came from Mrs. Angelund who lived above us on San Bruno Avenue. It was a dark wood cottage built on stilts to accommodate the hill that dropped under it. Connected to paved, level San Bruno by a short wooden bridge it was hidden under tall juniper trees. When I left the daylight on San Bruno to approach the doorway I felt as though I had entered the world of Hansel and Gretel. I would not have been surprised to see gnomes perched on the stacks of old newspapers that flanked the front door. The old door opened with a creak to my knock by what seemed to my eyes a bent, ancient crone.. There was no conversation except for my asking for eggs. She retired to a smoky, unlit room, returning a few minutes later with as many freshly laid eggs as were available. My mother usually went herself for a chicken which Mrs. Angelund handed over after having twisted its neck. It was up to my mother to pluck it, singe it and pull out the insides.

After the rains, the neighbors hiked up Black Hill to search for mushrooms. Watercress grew in the big ditch on the second half of Le Conte. Everybody had a vegetable and fruit garden in the back yard. Our fruit trees were dedicated to each child. Mine was the apricot, Lily claimed a cherry. When no fruit appeared my mother bought a big bag from the store and hung the cherries on the tree. Lily was delighted to find a miracle the next morning.

Tall, colored glass jars, usually amber and red, stood in the window of the drug store on Third Street where one bought cough medicine. When I was nine years old the doctor at the Lane Clinic suggested to my mother that I take Scot’s Emulsion cod liver oil to build me up. That weekend she’d invited several women friends from the Armenian church to our house for lunch. She gave me fifty cents and suggested I go to the drug store and pick up the cod liver oil. Several kids accompanied me as I proudly led the way. When we returned I found a glass of freshly squeezed orange juice which the doctor had recommended as a chaser. Digeen (Mrs.) Noonik, one of guests, soberly pointed out that it would keep me from catching tableclosis. It took me sometime to figure out she meant “tuberculosis.”Showing off—because I had no idea what it would taste like—I swallowed the oily tablespoon full of the stuff. Aack! Instant shock! I gagged, spit it out, dove under the round oak dining room table. I gulped down the juice someone had handed to me. I refused to emerge until my mother promised me I wouldn’t have to take cod liver oil ever again.

These same friends often visited with shopping bags on hand, anticipating a walk to the truck farms near Gilman Avenue. They returned with their bags filled with parsley and lettuce. Another excursion was the walk to Candlestick Cove to the dairy that occupied the land under the shadow of Black Hill. I accompanied them if it was not a school day. I don’t know exactly what they bought but I assume it was fresh butter and eggs. For years I feared cows after an episode of having to jump out of the path of a herd being driven to the barns; they made moaning sounds and their eyes were bloodshot and angry.

San Bruno Avenue in Portola District, 1908.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

There were other vendors. The iceman delivered his blocks whenever he spotted the cardboard sign “Ice Today” the Zarosi’s who lived next door hung in the front window. We didn’t have an ice box; perishables were kept in a cooler, a long narrow closet with a perforated back wall that took in the outside air. In naturally air-conditioned San Francisco it was sufficient to keep the butter, milk, and the essential magart, (starter for madzoon, the Armenian word for yoghurt) as well eggs and other edibles fresh. In any case, freezing food for future use was unthought of in the era of buying only what the family needed for the day or week. Soft drinks didn’t exist for us except as a treat when we went to Fleischacker’s playground or Golden Gate Park.

For items she needed for the Middle Eastern dishes my mother headed to the Crystal Palace Market on Ninth and Market. We looked forward to the excursion that took up most of the day as it entailed taking the #25 from its southern terminal to the end of the line at Fifth and Market.

Passengers disembarked in front of Paul’s Flower Stand that occupied the curb in front of Hale’s Department Store. Empty shopping bags in hand, we hiked up Market, past small shops and big stores such as Kress’ Five and Ten and Weinsteins’s Department Store. Entering the Crystal Palace, whose dome was glass latticed, was like being in a foreign country. The air was filled with the sound of vendors hawking their wares, strolling minstrels and bands playing from the balcony. The huge space—71,000 square feet on four acres—contained shops and stands selling not only foodstuff but pets, phonograph records, housewares (their ads boasted that they sold “everything under the sun” and no one tried to prove them wrong.)

My mother headed for the green grocer stands run by Armenians where she stocked up on eggplant, grape leaves, bell peppers and whatever else the truck farmers in our neighborhood couldn’t supply. When she was finished we stopped at the peanut butter stand and watched as the peanuts were dumped into a huge container, where they were crushed. I felt rather uncomfortable for a few minutes as I watched the flowing long brown line that provoked unpleasant comparisons but it was all forgotten when `we were offered a sample taste. The order for a quart was scooped into a white box, the kind ice cream came in, and taken home to be enjoyed.

We had other callers in the neighborhood. The familiar call of the junkman, “rags, bottles, papers,” brought out the housewives who were glad to get rid of the recyclables that the Sunset Garbage wouldn’t take.

Most welcome, though, was The Captain and His Pony. An easy-going gentleman came by equipped with a camera and a cowboy hat which he’d pop on the head of the child selected to sit on the pony, then would snap a picture. Each of us got to pose on the pony. The Captain usually let us ride the pony for a few minutes before leaving for the next house. We waited impatiently for the photos which came in a couple of weeks and which were saved forever.