Woodward's Gardens, c. 1860s

Historical Essays

Part One by Charles Lockwood

Part Two by Christopher Craig

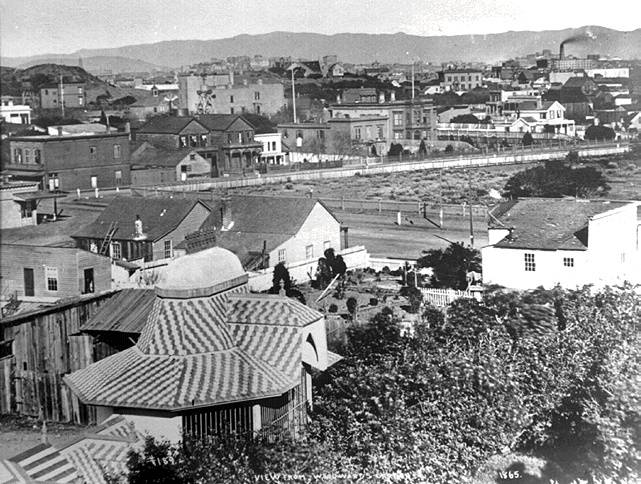

East bay hills looking from apx. Guerrero and 14th St. Woodward's Gardens is in the foreground.

Photo: Private Collection, San Francisco

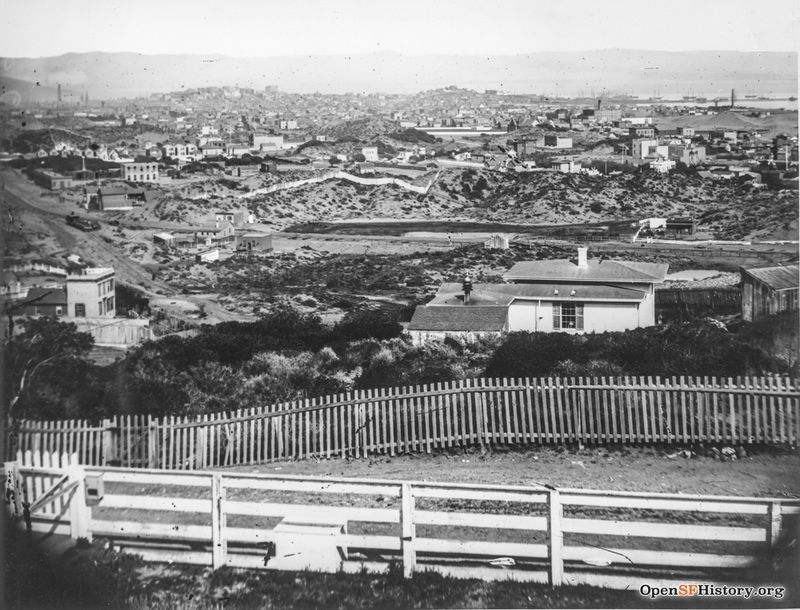

View southeast from slopes of Clinton Mound/Mint Hill overlooking Valencia and Market, 1865.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp27.6318

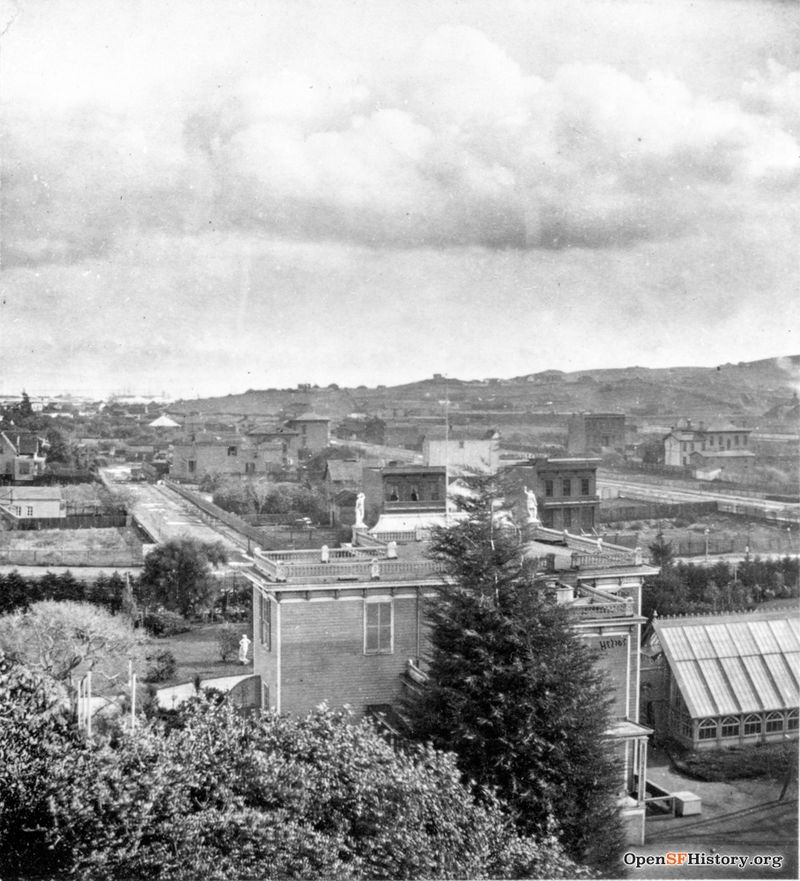

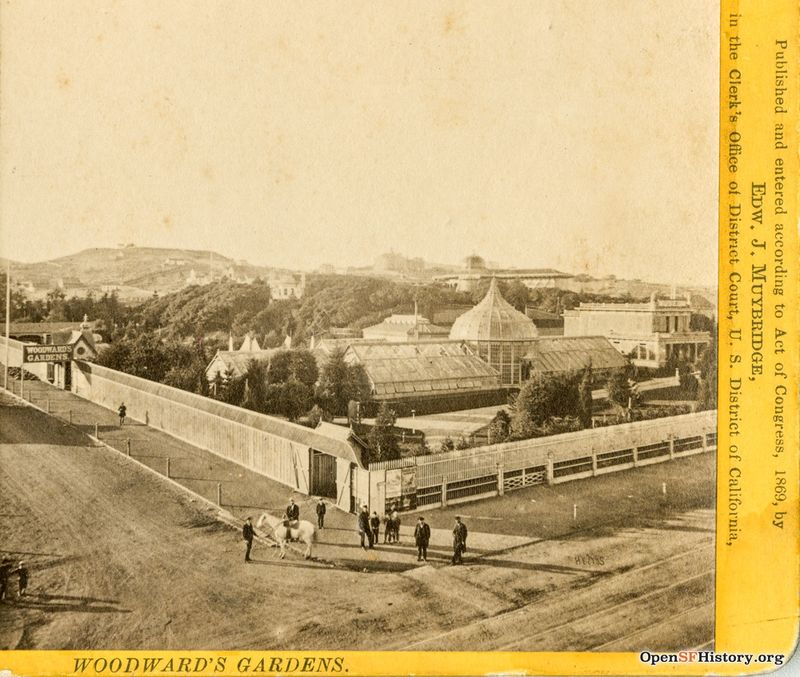

Easterly view from Woodward's Gardens: elevated view across Mission District to Potrero Hill, showing rear of museum and conservatory. Erie Street on other side of Mission.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp26.639

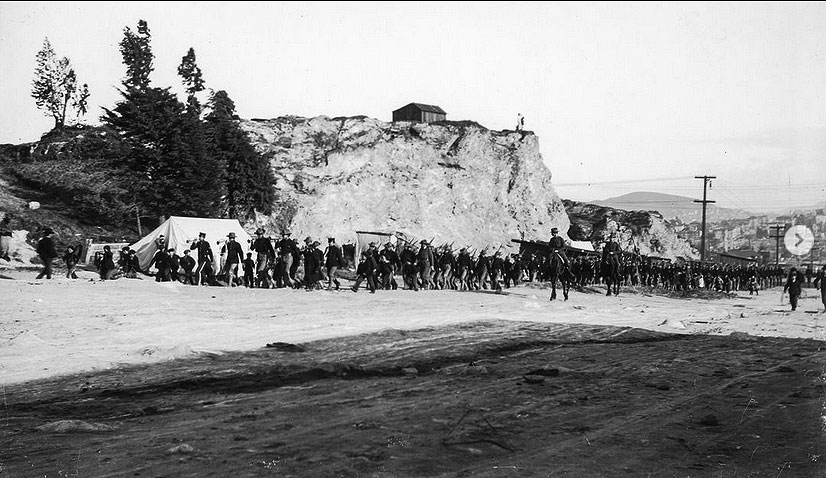

Market at Dolores, c. 1898, soon after the cut through Market Street opened up the road going west.

Photo: provenance unknown

Sarolta J. Cump's audio story about Woodward's Gardens, originally from the 2004 Audiozine "Long Ago and Right Now"

The largest and most popular amusement grounds in the Mission, indeed in the entire city, was Woodward's Gardens which Robert B. Woodward opened at his four-acre former country estate in 1866. Woodward did not permit alcoholic beverages on the premises, but that rule did not stop San Franciscans from flocking to this botanical gardens-amusement park-museum-outdoor theater-and-zoo all rolled into one.

After paying their admission fee, the first thing that visitors saw was Woodward's former home, converted into the Museum of Natural Wonders, which held stuffed bears, birds, fish, fossils, and mineral specimens, including a ninety-seven-pound gold nugget from the Sierra Butte mine.

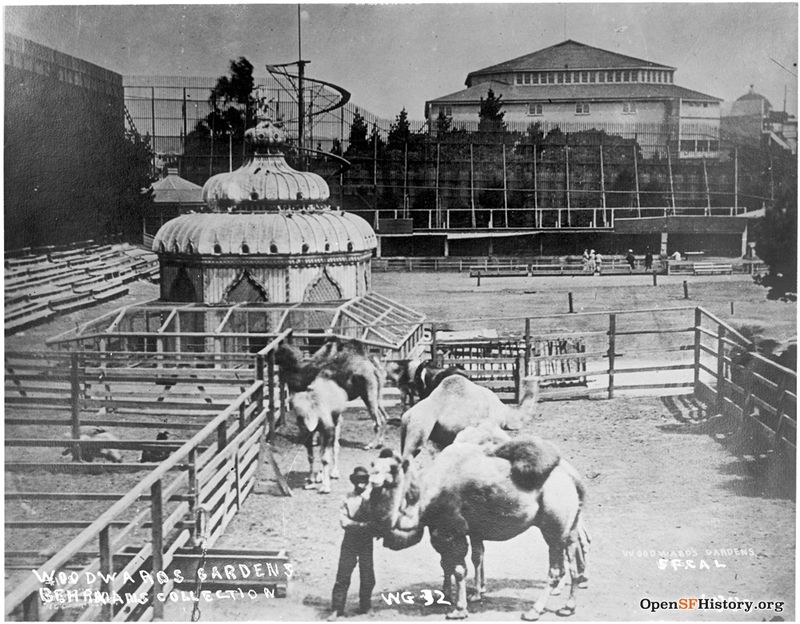

Camel corral, Woodward's Gardens, 1880.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp71.0545

Hillside with summer house, 1869.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp37.01617

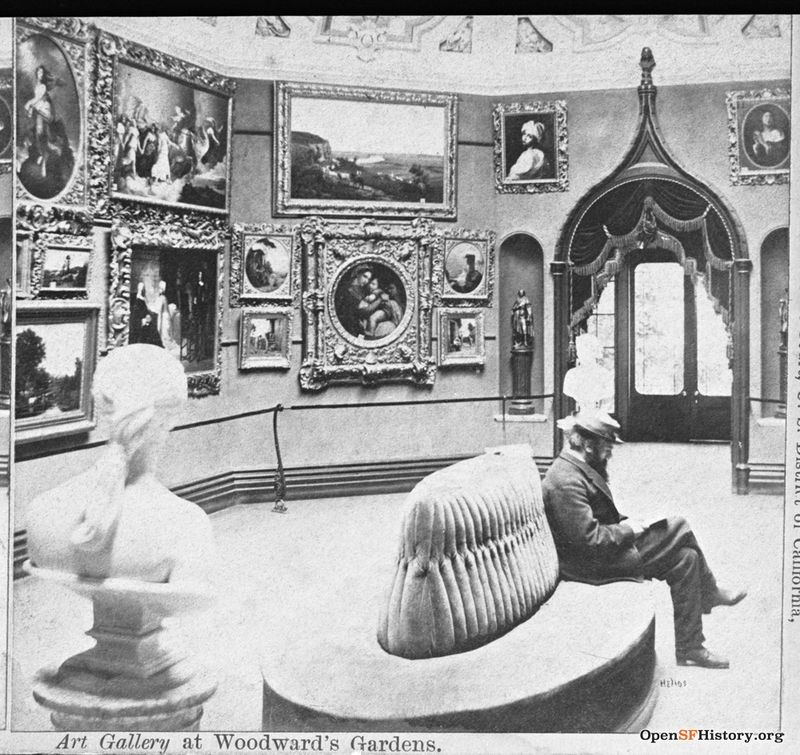

Next to the museum stood Woodward's Near Eastern-style conservatory, filled with exotic plants and flowers, and the art gallery, which displayed Victorian genre paintings and copies of old masters' works, plus sculpture like a copy of Hiram Powers' bust of California and a piece called Indian Girl at the Grave of Her Lover. Nearby, the rotary boat whirled around its circular track on the edge of a pond as the children on board laughed and screamed with delight.

Woodward's Gardens art gallery, c. 1870, with famed photographer Eadweard Muybridge seated.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp 37.01362

Behind the pond stretched gravel paths that passed fountains, streams, small lakes, hillocks, even manmade grottos and caverns. Many of the trees and shrubs at Woodward's Gardens had been imported from Europe, and each one wore a name tag. Tame animals like ostriches, deer, and small barnyard animals wandered freely through the grounds, and nearly 100 animals filled the separate "Zoological Department" on the other side of 14th Street. Near this zoo, Woodward built an amphitheater where up to 5,000 men, women, and children watched spectacles like the Delhi fire eaters, Siberian reindeer, Japanese acrobats, dancing bears, Roman chariot races, even Major Burke and his rifle review.

—by Charles Lockwood, originally published in New Mission News

At Woodward's Gardens, poem by Robert Frost

Woodward's Gardens

by Christopher Craig

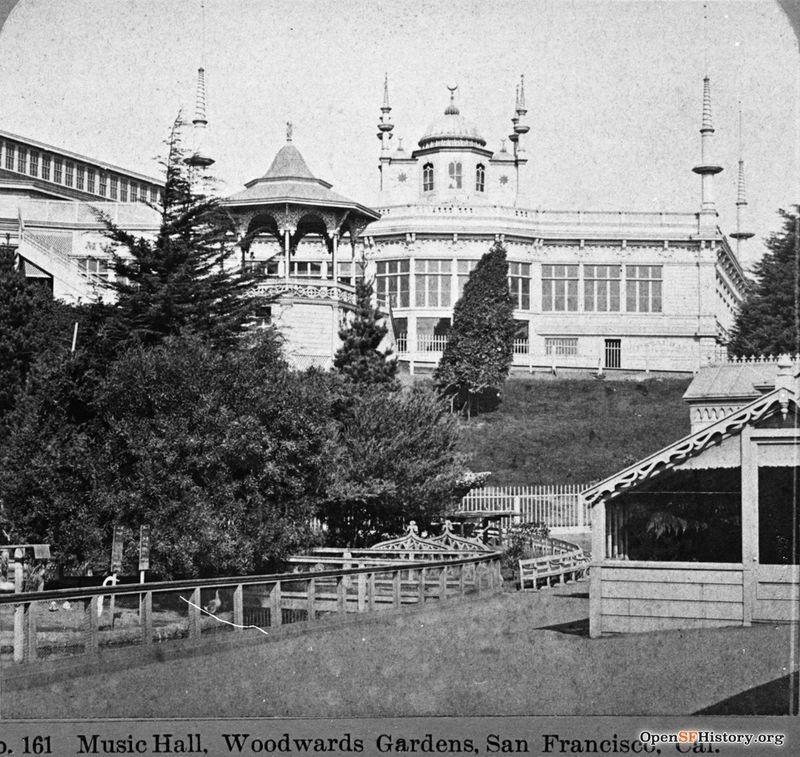

Music Hall, Woodward's Gardens, c. 1875

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp37.02291-R

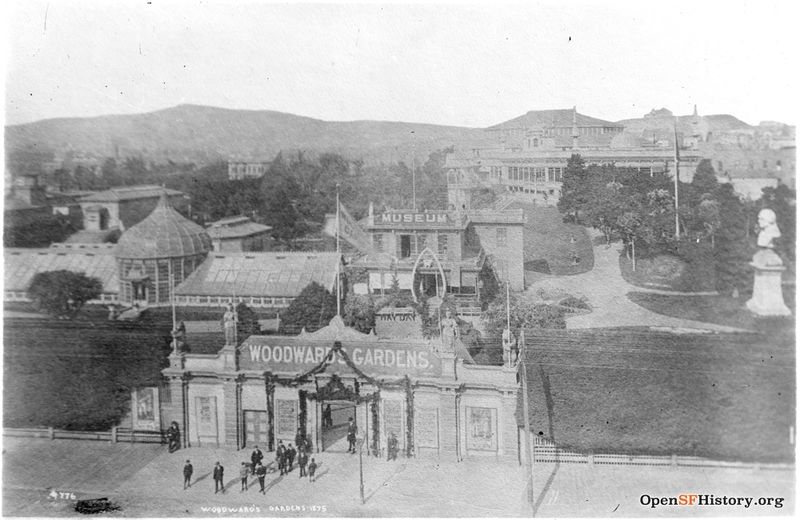

Woodward Gardens was a popular public amusement resort in operation between 1865 and 1891. It was formerly located within a two square block area bounded by Mission and Valencia, and 13th and 15th Streets. Wealthy hotel proprietor Robert B. Woodward bought the property in 1861, and moved his family into the former house of General Fremont that occupied the corner of Mission and 14th Streets. Over the next five years, he invested in beautifying the residence and grounds. A new main house was completed in 1862, and ornate fountains, lakes, and manicured gardens adorned the property.

Local interest in the private estate prompted Woodward to open the grounds commercially to the general public in 1865. Locals dubbed the grounds the "Central Park of the West," and the site became very popular for picnics and events. Woodward introduced a system of horse-drawn "bob-tail cars" that brought city residents to his resort from the downtown area, utilizing the wooden plank road, which stretched along Mission Street. After relocating his family to Napa, California, the main house was converted into a museum and was filled with stuffed animals, coins, stamps, and collectables given to him by sailors and world travelers that had stayed at his well-known hotel, the What Cheer House. Later structural expansions allowed Woodward to exhibit his large collection of fine art, oil paintings, statuary, and ceramics, which he accumulated from his trips to Europe.

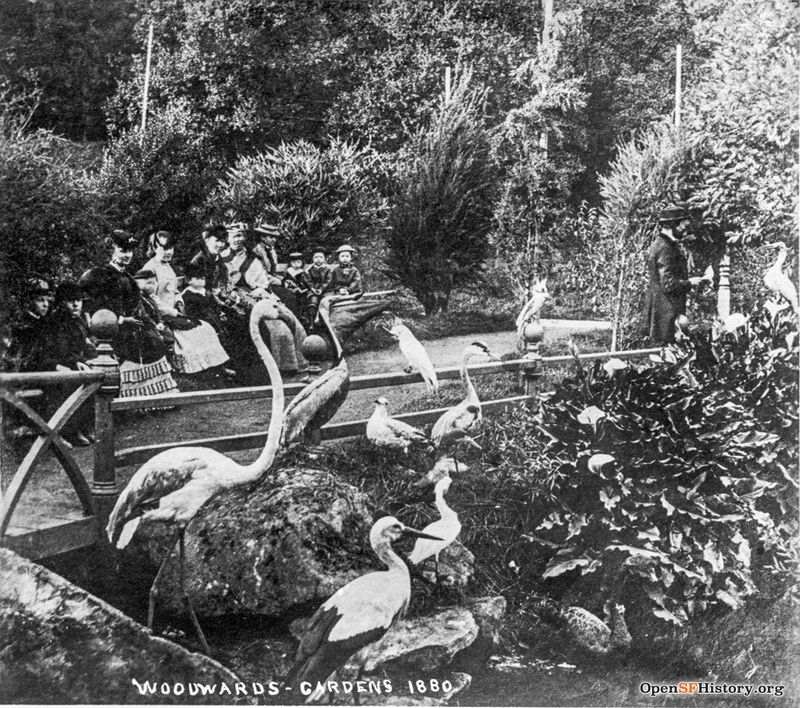

A conservatory was added which housed rare and exotic trees and tropical plants, and in 1873, he opened the first public aquarium on the West Coast, which featured marine specimens from around the globe. Other additions included an amusement pavilion with pipe organ music, a lunchroom, a restaurant, and a roller rink. On weekends, live entertainment was provided, including stage plays, bands, dancers, comedians, and circus-types performing all manner of feats and spectacles. One of the main draws to the park was the zoo. Ostriches, flamingos, deer, and domestic animals were allowed to roam the gardens unhindered, while wolves, bears, lions, camels, and monkeys were kept in larger pens and cages. As with Woodward's successful hotel, alcohol was not allowed on the premises, ensuring an environment that was relatively free of rabble-rousers and unsavory characters.

The main entrance to Woodward's Gardens. N.W. cor. 14th & Mission St., 1875. In April 1866, Woodward was elected president of the Board of Directors of San Francisco’s Omnibus Railroad Company, which ran horse-drawn streetcar lines across the city, including one that passed the imposing gates to his gardens. Soon after assuming leadership of the Omnibus Railroad, he opened his San Francisco estate to the public as Woodward’s Gardens, charging visitors a nominal fee for entry. The crowds that came to visit Woodward’s Gardens, of course, came and went on the omnibus line.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp71.0951

When Mr. Woodward died in 1879, the caretakers of his estate attempted to keep the park running, but as other city attractions opened, and the resort deteriorated in appearance and popularity, the park officially closed to the public in 1891. In February 1893, a California lion and two jaguars mysteriously died of poisoning in the gardens. By then, the menagerie was a run-down collection of “pulmonary monkeys and rheumatic lions.” Faced with the need to liquidate their assets, Woodward’s heirs put the entire collection up for auction in 1893. The auction itself was a final attraction for visitors who wished to remember Woodward’s Gardens of their youth. 75,000 articles in all were sold. Nothing remains of the once spectacular amusement resort except for photographs, ephemera, and the written reminiscences from those who saw it firsthand. A plaque commemorating the 19th century attraction hangs outside of a modern restaurant, named appropriately, "Woodward's Garden", located at 1700 Mission St. (at Duboce St.)

Bibliography

—Palmer, Mrs. Silas H, Vignettes of Early San Francisco Homes and Gardens: Program of the SF Garden Club, Woodward's Gardens, 1935

—Turrill, Charles B., California Notes, E. Bosqui & Co., 1876

More scenes of Woodward's Gardens

14th and Mission, 1869, original by Eadweard Muybridge.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp24.194a

Pelicans and Nature at Woodward's Gardens c. 1880

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp37.02887