Television invented in San Francisco!?: Difference between revisions

(categories and link to Jack LaLanne pop up) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

[[Lillie Coit's Tribute to Pyromania |Prev. Document]] [[The Sentinel Building |Next Document]] | [[Lillie Coit's Tribute to Pyromania |Prev. Document]] [[The Sentinel Building |Next Document]] | ||

[category:North Beach]] [[category:1920s]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:Inventions]] [[category:Famous characters]] | [[category:North Beach]] [[category:1920s]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:Inventions]] [[category:Famous characters]] | ||

Revision as of 13:53, 13 August 2008

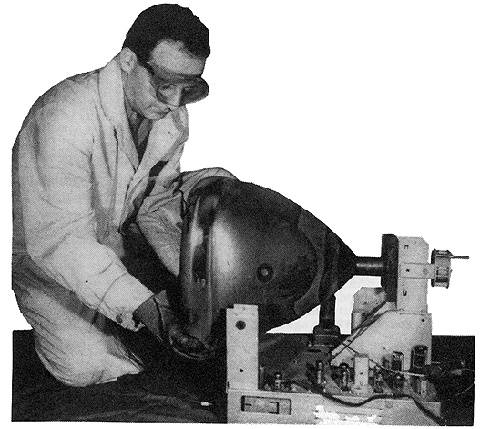

Philo T. Farnsworth at work.

Here at 202 Green Street, on September 7, 1927, a 21-year-old whiz kid named Philo T. Farnsworth transmitted images via cathode ray tube for the first time in human history. Or so goes the story. Actually, Farnsworth was the second to transmit an all-electronic television image; the first was V.K. Zworykin of R.C.A. Laboratories in New Jersey. But Farnsworth's invention, which paralleled Zworykins, was far more remarkable in that he did it on his own, without major corporate backing. Farnsworth's inspired tinkering eventually yielded 10 patents crucial to the development of television as we know it; today's TV sets still depend on several of them.

As an eccentric whose technical education had largely been gleaned from pulp science magazines, Farnsworth was an unlikely candidate in the great inventor sweepstakes. His college education consisted of one semester at Brigham Young University, after which he dropped out to start a radio repair shop, which quickly went bankrupt. Desperate, he took a job as a fund-raiser for Community Chest in the spring of 1926. A fellow fund-raiser, George Everson, listened eagerly to Farnsworth's ideas about transmitting images electronically. Before long, Everson agreed to put up $5,000, and the two set out for the west coast. After an abortive stint in LA, they moved to San Francisco and somehow obtained a meeting with an executive of the Crocker Bank. When a consulting engineer approved Farnsworth's proposal, Crocker and associates invested $25,000 and set up Farnsworth in a vacant loft at 202 Green Street.

Though faced with repeated setbacks stemming from Farnsworth's bizarre personality quirks and lack of engineering knowledge--compounded by his refusal to hire experienced engineers, whom he powerfully mistrusted--the operation began to bear fruit in the fall of 1927. Among the first transmitted images were dollar signs, so an associate could tell investors that he had seen dollar signs in Farnsworth's invention. Soon he had progressed to televising parts of motion pictures; the first demonstration showed an endless loop of Mary Pickford combing her hair.

The first long-distance demonstration came in 1930, when Farnsworth put a transmitter on top of his lab and broadcast to a directional antenna atop the Merchants Exchange Club at 465 California Street, the home of Moby Dick's harpoon.

Farnsworth's attempts to commercialize his invention met with limited success. In 1947, Farnsworth Television and Radio began producing television receivers; in the last half of 1948, the company lost $3 million, and in February 1949 IT&T bought out what was left. In the end, it was Farnsworth's brilliant failures, as much as his successes, that made him a legendary figure. In a nation where inventors, like assassins, are popularly supposed to be lone nuts rather than faceless agents of mega-bureaucracies, Farnsworth was one of the last who truly fit the bill.

--Dr. Weirde