San Francisco Tradeswomen Organizing at the City Level: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

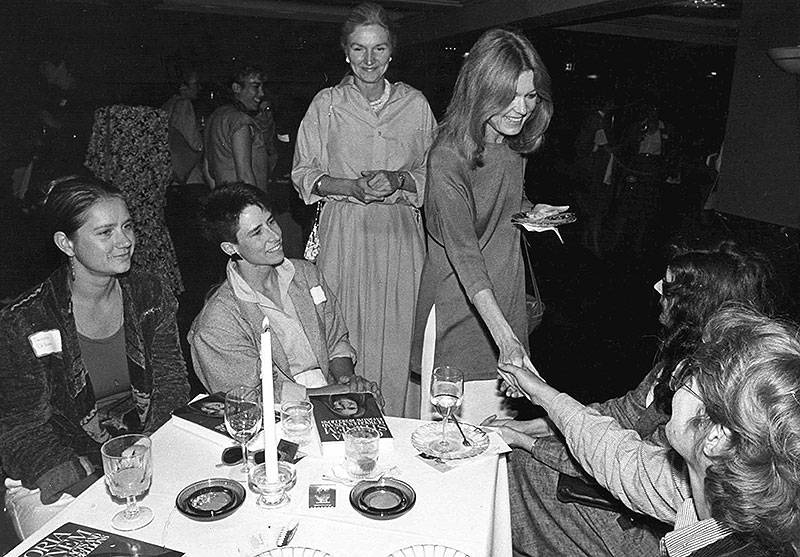

'''(left to right) Patty DeVlieg, MUNI engineer; Molly Martin, city electrician; Nancy Walker, SF Supervisor; Gloria Steinem, Diane Nygaard, Women in Transportation; Amy Reynolds, city plumber.''' | '''(left to right) Patty DeVlieg, MUNI engineer; Molly Martin, city electrician; Nancy Walker, SF Supervisor; Gloria Steinem, Diane Nygaard, Women in Transportation; Amy Reynolds, city plumber.''' | ||

''Photo | ''Photo courtesy Molly Martin, photographer unknown'' | ||

Tradeswomen activists changed our world from the personal realm up to the national and international. This is the story of San Francisco Women in Trades, one of hundreds of local organizations in cities across the country dedicated to the success of women in nontraditional blue-collar jobs. | Tradeswomen activists changed our world from the personal realm up to the national and international. This is the story of San Francisco Women in Trades, one of hundreds of local organizations in cities across the country dedicated to the success of women in nontraditional blue-collar jobs. | ||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

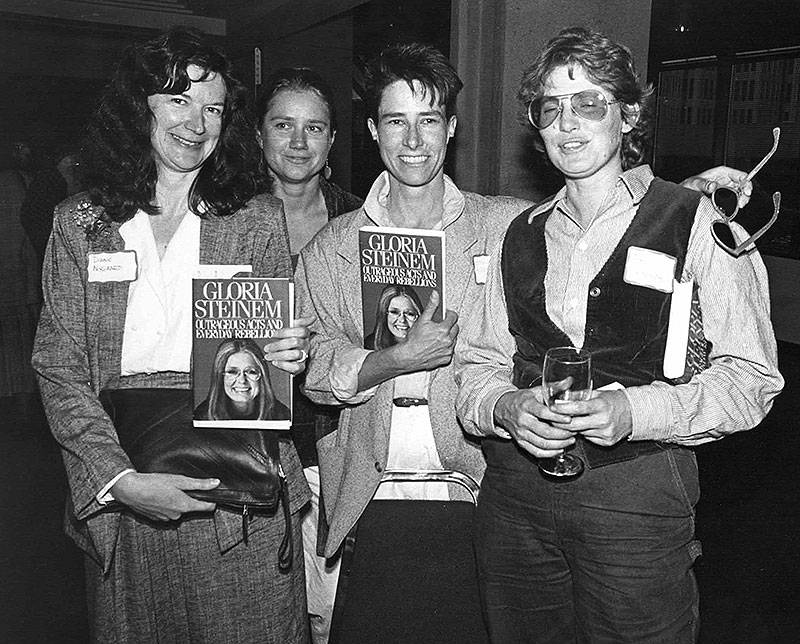

'''San Francisco Women in Trades contingent (left to right) Diane Nygaard, Patty DeVlieg, Molly Martin, Amy Reynolds''' | '''San Francisco Women in Trades contingent (left to right) Diane Nygaard, Patty DeVlieg, Molly Martin, Amy Reynolds''' | ||

''Photo | ''Photo courtesy Molly Martin, photographer unknown'' | ||

Tradeswomen in city departments were isolated and the targets of harassment, so we got together and formed an organization to advocate for ourselves. There may have been as many as ten of us at the first meeting, which we held at El Rio, a bar on Mission Street. We christened our organization San Francisco Women in Trades (SFWIT). It was about 1983. We began to meet on a regular basis. | Tradeswomen in city departments were isolated and the targets of harassment, so we got together and formed an organization to advocate for ourselves. There may have been as many as ten of us at the first meeting, which we held at El Rio, a bar on Mission Street. We christened our organization San Francisco Women in Trades (SFWIT). It was about 1983. We began to meet on a regular basis. | ||

Revision as of 15:05, 3 December 2021

Historical Essay

by Molly Martin

(left to right) Patty DeVlieg, MUNI engineer; Molly Martin, city electrician; Nancy Walker, SF Supervisor; Gloria Steinem, Diane Nygaard, Women in Transportation; Amy Reynolds, city plumber.

Photo courtesy Molly Martin, photographer unknown

Tradeswomen activists changed our world from the personal realm up to the national and international. This is the story of San Francisco Women in Trades, one of hundreds of local organizations in cities across the country dedicated to the success of women in nontraditional blue-collar jobs.

The tradeswomen movement lacks power in numbers. To succeed we must find allies and collaborate with others. We depend on a few dedicated advocates.

Silvia Castellanos may be one of the most effective and most unsung heroines of the Tradeswomen Movement in San Francisco. I think Silvia is responsible for securing civil service employment for more women in the trades than any single person in the city.

I first met Silvia in 1982 when she was working at the Equal Employment Opportunity office in San Francisco City Hall. I had managed to get work out of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) Local 6 union hall for a couple of seasons. Then, at the end of 1981, a notorious foreman universally hated by Local 6 hands laid me off. He always laid off workers at Christmas, and that’s what happened to me. Work dried up and I wasn’t able to get dispatched out of the hall again after that.

I spent this period of unemployment trying to raise money for Tradeswomen Inc. (TWI), the nonprofit we founded in 1979. A group of tradeswomen volunteers had just started the quarterly Tradeswomen Magazine and we imagined we could pay printing costs by selling ads. We were naïve, not truly cognizant of how hated we were by both unions and contractors. One idea was to approach employers who might need to fulfill affirmative action requirements. The City of San Francisco had committed to diversifying its workforce and it had a long way to go where the trades and women were concerned.

When I called the city EEO office, Silvia answered. Her job was to make sure the city was meeting its affirmative action goals for women in nontraditional jobs. We agreed to meet in her office to strategize.

The EEO office in city hall still retained some of the building’s original oak furniture and woodwork, but by the 1980s metal cubicles had been plunked down into the grand, high-ceilinged space. With no idea what she looked like, I hunted for her cubicle. A stunningly beautiful woman with waist-length black hair greeted me. When I got a little closer, I saw she was wearing earrings with a double female symbol. She was a sister dyke! And she was out!

Silvia talked like a character in Batman. She would punctuate her sentences with the kind of exclamations in the bubbles above the heads of cartoon characters: Splat! Boom! Kapow! Great Scott! I liked her immediately. I knew then that this would be the start of a very productive relationship.

No money ever came through from EEO for Tradeswomen Magazine ads, but when I met Silvia I found an important ally in our struggle. For the next decade we would work together to even the playing field for women in city employment.

Because of that meeting I got a job. The city had temporary openings for Electrician, classification 7345, in several departments. Silvia gave me all the information and encouraged me to apply. City departments were notoriously resistant to hiring women and minorities, especially for trades jobs, which had been the exclusive property of their respective unions. Until a citywide strike in 1976, the IBEW had rewarded members it considered deserving with city jobs. It had been like the old ward system in Chicago. Of course the deserving members had all been white men. After the strike, the trade unions’ hold on city jobs was loosened. City electricians were still organized by IBEW Local 6, but as a different bargaining unit. Local 6 hands didn’t apply for the jobs, and the union pretty much ignored city workers.

I applied at the San Francisco Water Department (SFWD) and on May 5, 1982 they hired me on as a temporary electrician. My job was to install and maintain the pumps and associated motors and equipment in the city. I was soon joined by Amy Reynolds, the city’s first female plumber; Marty Kashuba, a painter; and Joan Annsfire, drafter. It only takes one woman to call a meeting. It only takes two to form a group. In the TV show Cagney and Lacy met in the women’s bathroom at the NYPD. We met in the women’s bathroom at the SFWD.

SF Women in Trades

I was on the cusp of a (small) wave of tradeswomen working in city departments. A 1973 class-action lawsuit had been filed by women and people of color against the San Francisco Police Department. A consent decree reached in 1978 directed the Equal Employment Opportunity Office to end employment discrimination within the Civil Service Commission which included bringing women into a wide range of nontraditional jobs. But, unlike firefighters and police, tradeswomen were spread out into all the different departments and each of us was the only woman working in a male-dominated workplace.

San Francisco Women in Trades contingent (left to right) Diane Nygaard, Patty DeVlieg, Molly Martin, Amy Reynolds

Photo courtesy Molly Martin, photographer unknown

Tradeswomen in city departments were isolated and the targets of harassment, so we got together and formed an organization to advocate for ourselves. There may have been as many as ten of us at the first meeting, which we held at El Rio, a bar on Mission Street. We christened our organization San Francisco Women in Trades (SFWIT). It was about 1983. We began to meet on a regular basis.

When we gathered, the stories the women told were familiar. Women were being subjected to unbelievable harassment—what became known later as hostile work environment. Sexual harassment on the job was, from the beginning, our biggest issue. Its prevalence was the reason the city had trouble retaining women in these well-paying sought-after jobs. An intractable sexist male culture reigned in every one of the city’s corporation yards and shops. We wanted to change it and one way to do that was to increase the number of women on the job. We knew we needed a critical mass. The consent decree called for ten percent women in police and fire departments and we made that our goal.

We sought out supportive women on the 11-member Board of Supervisors. I knocked on the door of Sup. Nancy Walker and found her aide, Kate Monico-Klein, who said she’d do whatever she could to help our cause. The other Supervisor we approached was Louise Renne, who agreed to support an ordinance regarding sexual harassment. At the time Dianne Feinstein was the first female mayor of San Francisco. We didn’t see her as much of a feminist, even though lesbian activists Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon were big supporters as she had helped them organize the SF Commission on the Status of Women (COSW) and make domestic violence a prominent issue.

One of the many projects SFWIT worked on with Sup. Walker was an initiative for comparable worth—the idea that women in jobs with requirements and education equivalent to men’s would be paid the same as men. One example often used was truck driver and clerk. Truck drivers, 100 percent of them men, made about three times as much as clerks, 80 percent of them women.

During this campaign, tradeswomen came to Sup. Walker’s office for a strategy meeting. As we waited in the anteroom, we introduced ourselves and told how we got into our city trades jobs. I was surprised to learn that every single woman in that room had found her job through Silvia Castellanos, who worked quietly behind the scenes to overturn employment discrimination.

Silvia authored a newsletter with information about job openings and achievements of tradeswomen. She helped us organize gatherings of sisters to meet and network with each other. At one event the feminist Gloria Steinem spoke. I had slipped my card into her pocket and told her of SFWIT and our initiatives. When she mentioned us onstage, a big cheer went up from the crowd. Gloria stepped back, surprised. It seemed like the place was filled with tradeswomen! There were still only a few of us, but we had succeeded in letting the feminist community know about our struggles. That was a highlight for us.

Silvia Castellanos: Before Covid, there was another ‘disaster’ where City employees were reassigned and dispatched to other duties as all City employees are Disaster Service Workers... This was in 2007 when the Cosco Busan container ship struck a tower of the Bay Bridge and over 54,000 gallons of oil spewed into SF Bay. I was assigned to register and organize volunteers- people came from all over the City to help clean up the spill...

SFWIT worked with EEO to transform the city’s hiring process to bring more women into trades jobs. We pushed the city departments to respond to sexual harassment complaints. We demanded sexual harassment training not just for managers, but also for the coworkers responsible for most of the harassment. We made sure that women sat on civil service test panels and we worked every angle trying to increase the number of women in trades in the city. The EEO office developed job-related criteria for minimum qualifications and using job-related examinations for selection. Targeted recruitment was used to identify “qualified” women and people of color. No one was lowering standards. But recruitment was not enough. Support, encouragement, and mentoring were necessary for retention. They addressed the isolation of being the only woman on the job and they set up a process to resolve sexual harassment complaints. Unfortunately, women who spoke out or filed complaints often faced retaliation.

Commission on the Status of Women

In 1987, as Feinstein was being termed out, SFWIT became one of the first organizations to pledge support for the mayoral campaign of Art Agnos. We were part of a huge coalition of community organizations working for a change in city politics that would empower women and minorities in jobs and on city commissions. Art won with 70 percent of the vote, and we joined a rainbow of supporters at the party on election night. It felt like the night of George Moscone’s election, the legendary “people’s “ mayor, who had been assassinated in 1978 along with Supervisor Harvey Milk, one of the nation’s first openly gay politicians. We community organizations felt empowered to change our world.

Tradeswomen wanted the COSW to focus on more than just the single issue of domestic violence. We wanted the commission to do something about sexual harassment in the city’s workplaces, especially in the trades departments where there were few women. I had applied to be appointed to the COSW during the Feinstein administration, but didn’t make the cut. Feinstein insisted her commissioners never question her positions and always tow the political line. I wouldn’t have been a good fit.

Agnos pledged to make the COSW into a regular city department with subpoena powers, and he did. I applied as a representative of SFWIT with the agenda of ending sexual harassment at city workplaces and helping bring more women into city trades jobs. I took an hour off from my electrician job for the interview, which took place in the mayor’s office at City Hall. I was relieved when Agnos told me he didn’t expect commissioners to tow the line and always agree with his agenda. But he asked that we bring any differences to his attention for discussion before going public. We sat in chairs opposite each other, and as I crossed my legs I accidentally kicked him in the shin with a heavy construction boot. I guess I didn’t lose points for that, as I was appointed to the COSW. Agnos also moved ahead on a consent decree about women and minorities in the fire department that Feinstein had opposed, which set in place the machinery to integrate the fire department. During the Agnos administration I worked with MUNI trainer Debi Horen to highlight women in nontraditional city jobs in a series of recruitment videos that were played on the city TV station. People would tell me they’d seen me on TV at 6 on Sunday morning, confirming that San Franciscans have weird TV viewing habits.

Silvia Castellanos continued to work with SFWIT until her job changed to advocating for workers with disabilities in city employment. In 1996, when state Proposition 209 made affirmative action illegal for public employment, contracting, and education, the city seemed only too happy to close the coffin. EEO discontinued the practice of targeted recruitment. We had succeeded in increasing the numbers of tradeswomen, but without a recruitment program the numbers began to decline. I had moved to the job of electrical inspector in the Department of Building Inspection so I could no longer be counted as an electrician.

I hadn’t been in touch with Silvia, but one day in the 90s as I sat at my inspector desk, she called me to report that the recent numbers of tradeswomen were dismal. It was a sad moment for us. Silvia wanted to revive our efforts, but that was no longer her job and the tradeswomen community lacked money and resources (not that we had ever had either but we were burned out).

The consent decree was lifted when the police and fire department goals for women were met. Interviews done by the COSW for a gender analysis of nontraditional occupations in 2017 also show that city tradeswomen still suffer from isolation and harassment on their jobs. My cohort of tradeswomen has now retired and there are still only about three percent female city trades workers.

Our efforts were more than just a numbers game. We did change peoples’ attitudes about women in nontraditional work. Women working in construction and maintenance trades are no longer an anomaly.

Silvia Castellanos retired in 2019 and now we depend on a new generation of tradeswomen activists and allies to continue our work. Silvia offers parting words: “The struggle is real and allies are important. We’ve got to suss them out, find them, grow them and acknowledge them so that together we get ahead and farther.”