Murals: WPA to 1960s: Difference between revisions

(added photo) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

[[Douglas Tilden: Monument Sculptor | Prev. Document]] [[Community Murals | Next Document]] | [[Douglas Tilden: Monument Sculptor | Prev. Document]] [[Community Murals | Next Document]] | ||

[[category:Public Art]] [[category:Mission]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:1980s]] [[category:murals]] [[category:2000s]] | [[category:Public Art]] [[category:Mission]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:1980s]] [[category:murals]] [[category:2000s]] [[category:Reclaiming San Francisco]] | ||

Revision as of 20:46, 21 November 2021

Historical Essay

by Timothy W. Drescher

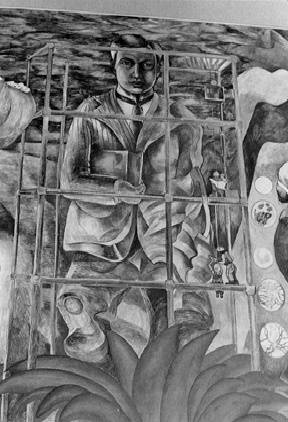

Diego Rivera's enormous engineer-worker in his fresco for the SF Art Institute was inspiration for Chuy Campusano in the B of A mural, "Homage to Siqueiros" (above). -- Timothy Drescher, from SF Bay Area Murals, Pogo Press, 1998

The sixties (the period from 1960 to approximately 1974) saw mass political activism at unprecedented levels throughout the United States. Beginning in mid-decade, artists and community activists began painting grassroots murals on the walls of their neighborhoods, a movement which added community to the historical mural tradition. Not since the earliest cave paintings had artists engaged in mural painting with community residents. Earlier murals were painted at the behest of various aristocrats, or were painted for the general population; public art, but not community art. An example of the shift from New Deal to community murals can be seen in two separate San Francisco murals, one painted in Coit Tower and the other in the Mission District.

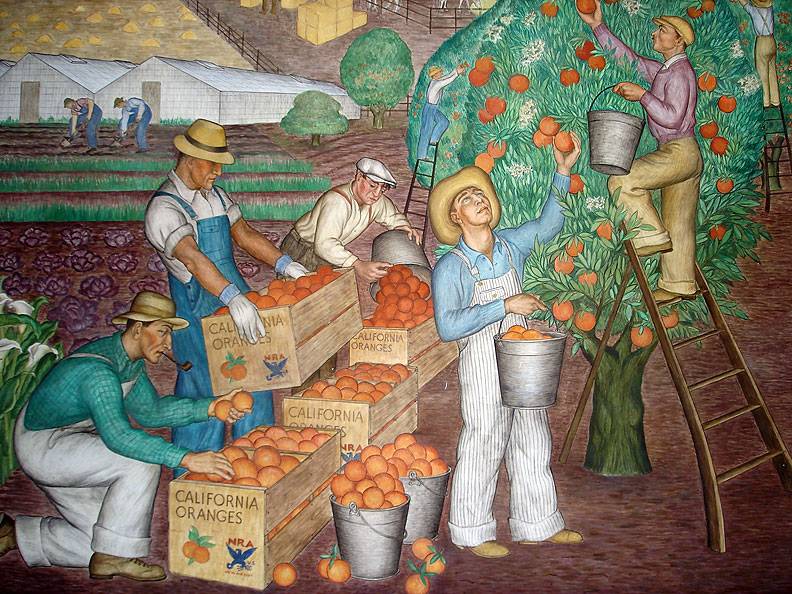

Orange pickers in California fields, 1934.

Maxine Albro, Coit Tower, photo by Chris Carlsson

The public art images of the New Deal, with very few exceptions, tended more to narrate history than grapple with the realities and complexities of multiple determinant histories. Maxine Albro's Coit Tower fresco, painted in 1934, depicts exclusively white workers in the orchards and flower farms of California, busily harvesting the state's rich agricultural bounty under the aegis of the National Recovery Act. That the state's labor force had never been monolithic in race or attitude went unmentioned.

Las Lechugeras mural by Juana Alicia, photo by Chris Carlsson

La Llorona’s Sacred Waters mural by Juana Alicia on same wall at York and 24th Streets, replacing her earlier mural Las Lechugeras.

Fifty years later, Juana Alicia painted Las lechugueras/The Women Lettuce Workers across town at 24th and York Streets, determined to articulate a different reality. The style is still basically realistic, and is also beautifully painted. The mural shows women lettuce workers following behind a harvester, whose pace is set by the bosses in the background (or is it the Immigration Service, the dreaded migra?). The women, including one visibly pregnant, are being sprayed with pesticides as they work.

The impact of the more recent mural indicates a major shift from the New Deal piece, and not least in the differences is the fact that it was painted on the street, and not inside a building (Coit Tower). The mural's audience is invited not only to behold the finished image, but to observe the process of its painting, with the consequent opportunity for discussion with the muralist while she painted.

--Excerpted from the essay "Street Subversion: The Political Geography of Graffiti and Murals" by Timothy W. Drescher in Reclaiming San Francisco: History, Politics, Culture City Lights Books, 1998