Union and Employers: 1901 to 1919: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

added photos |

||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

Initially, many of the draymen supported the teamsters’ action, but when the Employers’ Association formed the Merchants’ Drayage and Warehouse Company to compete with the Draymen’s Association, they swung against the union and yielded full control over events to the Employers’ Association. One draying company after another locked out their workers for refusal to haul goods of the nonunion company. Eventually the Teamsters voted that all their members should strike. When unionized beer bottlers refused to handle goods delivered by nonunion drivers, their employers declared an open shop. Other firms also discharged employees who refused to load or unload wagons driven by strikebreakers. The teamsters and their sympathizers, locked out and on strike, joined several strikes already in progress: restaurant cooks and waiters, bakers and bakery wagon drivers, metal polishers, and the fourteen-union Iron Trades Council, striking as part of a nationwide effort against the National Metal Trades Association. Earlier in the summer there had been strikes of butchers and carriage workers; the latter settled only when the Teamsters’ Union had threatened to stop deliveries to nonunion carriage companies.(20) | Initially, many of the draymen supported the teamsters’ action, but when the Employers’ Association formed the Merchants’ Drayage and Warehouse Company to compete with the Draymen’s Association, they swung against the union and yielded full control over events to the Employers’ Association. One draying company after another locked out their workers for refusal to haul goods of the nonunion company. Eventually the Teamsters voted that all their members should strike. When unionized beer bottlers refused to handle goods delivered by nonunion drivers, their employers declared an open shop. Other firms also discharged employees who refused to load or unload wagons driven by strikebreakers. The teamsters and their sympathizers, locked out and on strike, joined several strikes already in progress: restaurant cooks and waiters, bakers and bakery wagon drivers, metal polishers, and the fourteen-union Iron Trades Council, striking as part of a nationwide effort against the National Metal Trades Association. Earlier in the summer there had been strikes of butchers and carriage workers; the latter settled only when the Teamsters’ Union had threatened to stop deliveries to nonunion carriage companies.(20) | ||

[[Image:California Baking Company at Fillmore and Eddy wagons ready to distribute bread courtesy Society of California Pioneers.jpg|800px]] | |||

'''California Baking Company at Fillmore and Eddy, wagons ready to distribute bread in 1908.''' | |||

''Photo: courtesy Society of California Pioneers'' | |||

[[Image:California Baking Company bake shop2 courtesy Society of California Pioneers.jpg|800px]] | |||

'''California Baking Company bakeshop at Fillmore and Eddy Streets.''' | |||

''Photo: courtesy Society of California Pioneers'' | |||

Most union leaders of 1901 remembered vividly how the Manufacturers’ and Employers’ Association of 1891 had decimated union after union. Determined to prevent a recurrence of those events, convinced (in Furuseth’s words) that the “employers are determined to wipe out labor unions one after another,” the city’s labor leaders took stock of their resources, realized they could never hope to match the estimated half-million dollar raised by the Employers’ Association, and understood that the BTC would never join if the Labor Council called a general strike. Concluding that the survival of the Teamsters—and many other unions as well—depended on labor’s ability to convince the Employers’ Association to back down, the City Front Federation voted to shut down the waterfront.(21) | Most union leaders of 1901 remembered vividly how the Manufacturers’ and Employers’ Association of 1891 had decimated union after union. Determined to prevent a recurrence of those events, convinced (in Furuseth’s words) that the “employers are determined to wipe out labor unions one after another,” the city’s labor leaders took stock of their resources, realized they could never hope to match the estimated half-million dollar raised by the Employers’ Association, and understood that the BTC would never join if the Labor Council called a general strike. Concluding that the survival of the Teamsters—and many other unions as well—depended on labor’s ability to convince the Employers’ Association to back down, the City Front Federation voted to shut down the waterfront.(21) | ||

Revision as of 11:50, 2 November 2021

Historical Essay

by William Issel and Robert Cherny

Streetcars on Van Ness between 23rd and 24th in the Mission, looking north, Oct. 1911. Repeated strikes in the first years of the 1900s led to the eventual demise of the carmen's union in 1908.

Photo: courtesy SFMTA photo archive, U03245

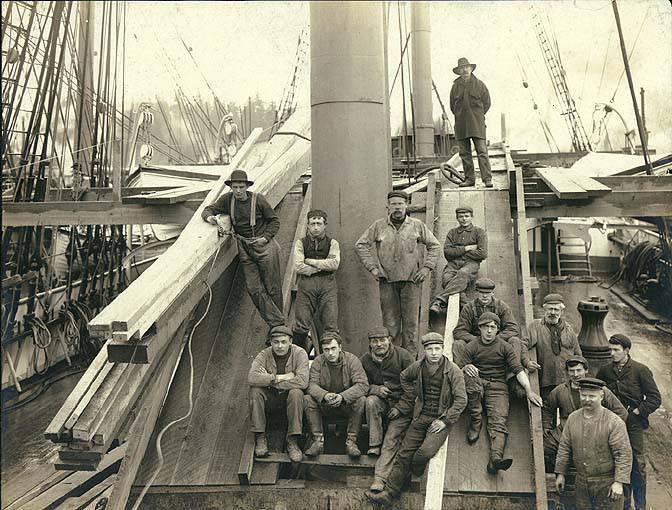

This shows a lumber crew in Washington State between 1893 and 1906, similar to waterfront workers in San Francisco.

Photo: University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, UW3101

San Francisco’s economy in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries depended heavily on the waterfront. The men who worked aboard ship, loaded and unloaded cargo, and transported goods to and from the docks had few skills; most were young and single. Just as sailors found work through boardinghouse keepers, so longshoremen turned out for the “shape-up,” in which potential workers assembled at a pier when a ship was to be loaded or unloaded, and the foreman hired some for that job. For sailors and longshoremen, work was temporary and typically performed under conditions of harsh discipline and low wages. Although the first recorded sailors’ strike came in 1850 and longshoremen struck the next year, most early efforts at unions were short-lived.(15)

Waterfront Unions

Sailors established a more permanent union in 1885 when they formed the Coast Seamen’s Union with assistance from the International Workingman’s Association. This group merged with the Steamship Sailors’ Union in 1891 to produce the Sailors’ Union of the Pacific (SUP) and the SUP soon established itself as one of the largest labor organizations in the western United States. Paul Scharrenberg, editor of the SUP’s weekly newspaper, Coast Seamen's Journal, described the SUP to the Commission on Industrial Relations in 1914 as “a real ‘one big union’ ” for sailors. “It covers the entire Pacific coast. There are no locals. A man who is a member of that union can sail anywhere between here and the coast of Africa. That is the jurisdiction of the seamen's union of the Pacific coast.” The SUP maintained branch offices up and down the coast and eventually in New York, and it helped organize not just sailors, but also marine firemen, cooks and stew¬ards, and Alaska fishermen.(16)

Andrew Furuseth, born in Norway and conversant in English. German, Dutch, French, and the Scandinavian tongues, led the SUP for nearly fifty years. Furuseth served as secretary (initially the only paid position in the SUP) from 1887 to 1892 with some interruptions for returns to the sea, and then without interruption from 1892 to 1936. He helped create the International Seamen's Union and served as its president in 1897–1899 and from 1908 to his death in 1938. Walter Macarthur, born in Scotland, edited the Coast Seamen's Journal from 1895 to 1913, and Scharrenberg, Macarthur's successor as editor and secretary-treasurer of the State Federation of Labor after 1911, worked closely with Furuseth.(17)

The early longshore unions lacked such durable leadership, but they had existed on the waterfront since the 1850s and 1860s. One of them, the Riggers’ and Stevedores' Union, survived from 1853 until the 1920s, but employers controlled it for a time in the late nineteenth century. A number of longshore workers’ unions emerged in the 1880s, notably the Longshore Lumbermen in 1880, two stevedores' groups in 1886, and a brick-handlers’ union and stevedore engineers’ union in 1887. In 1888, these groups joined with three seamen's unions, three unions of ship repair workers (riggers, caulkers, and shipwrights), and a union of wharf builders to form a short-lived Council of Wharf and Wave Unions. Although this effort at coordinated action lasted only a year, the membership included all the organized trades on the waterfront at the time. Another short-lived effort at a council in 1891 included most of the same unions.(18)

In February 1901, the City Front Federation united the SUP, the longshoremen’s unions, and the new Teamsters’ Local Union 85, posing the potential for arresting the city's economic heartbeat should they ever vote to shut down the waterfront. An Employers' Association appeared two months later, led by prominent merchants and manufacturers. The association kept its membership, financial resources, and governing board secret but publicized its commitment to the open shop and its guiding principle: disputes between employer and employee should be settled “without interference from the officers or members of any labor organization.” Association bylaws specified that no member could settle with a union without permission from the association executive committee. Centralized power now faced centralized power. At this juncture, the Epworth League, a Methodist young people’s association, contracted with a nonunion drayage company to haul convention baggage, and that company subcontracted part of the task to a unionized company. The Teamsters’ Union agreement with the Draymen’s Association specified that no teamster was to work for a draying company not a member of the association. Teamster adherence to this contract became the immediate casus belli for San Francisco’s labor war of 1901.

The 1901 Strike

Initially, many of the draymen supported the teamsters’ action, but when the Employers’ Association formed the Merchants’ Drayage and Warehouse Company to compete with the Draymen’s Association, they swung against the union and yielded full control over events to the Employers’ Association. One draying company after another locked out their workers for refusal to haul goods of the nonunion company. Eventually the Teamsters voted that all their members should strike. When unionized beer bottlers refused to handle goods delivered by nonunion drivers, their employers declared an open shop. Other firms also discharged employees who refused to load or unload wagons driven by strikebreakers. The teamsters and their sympathizers, locked out and on strike, joined several strikes already in progress: restaurant cooks and waiters, bakers and bakery wagon drivers, metal polishers, and the fourteen-union Iron Trades Council, striking as part of a nationwide effort against the National Metal Trades Association. Earlier in the summer there had been strikes of butchers and carriage workers; the latter settled only when the Teamsters’ Union had threatened to stop deliveries to nonunion carriage companies.(20)

California Baking Company at Fillmore and Eddy, wagons ready to distribute bread in 1908.

Photo: courtesy Society of California Pioneers

California Baking Company bakeshop at Fillmore and Eddy Streets.

Photo: courtesy Society of California Pioneers

Most union leaders of 1901 remembered vividly how the Manufacturers’ and Employers’ Association of 1891 had decimated union after union. Determined to prevent a recurrence of those events, convinced (in Furuseth’s words) that the “employers are determined to wipe out labor unions one after another,” the city’s labor leaders took stock of their resources, realized they could never hope to match the estimated half-million dollar raised by the Employers’ Association, and understood that the BTC would never join if the Labor Council called a general strike. Concluding that the survival of the Teamsters—and many other unions as well—depended on labor’s ability to convince the Employers’ Association to back down, the City Front Federation voted to shut down the waterfront.(21)

From July 30 to October 2, during the height of the harvest season, the City Front Federation remained on strike. Mayor James Phelan tried to mediate but quickly discovered that the Employers’ Association discouraged his efforts. “The vital principle involved in the present controversy,” the association announced, “is that of non-interference by the labor unions, or their representatives, with the conduct of the business of employers.” Mediation would compromise this principle. The association continued: “The principle thus involved may be surrendered by the employer, but it cannot be compromised.” The association remained convinced that the only acceptable labor relations were those between employers and individual employees. Mike Casey, leader of the teamsters, responded: “That is plainly saying to us that we may have ‘smokers’ or something of that sort as a result of the existence of unions, but that we shall not utilize the organization for the purpose they have been designed to serve.”(22)

From the beginning, the Employers' Association used strikebreakers. These nonunion drivers immediately became the focus of strikers’ antagonism; the hoots and jeers thrown at them were accompanied at times by bricks and stones. City police, assigned to ride the wagons driven by nonunion drivers, occasionally assisted the inexperienced drivers. The Employers’ Association soon replaced city police with private guards given the status of special police. Strikebreakers and employers secured permits to carry concealed weapons. According to the Examiner, the only daily newspaper sympathetic to the strikers, police were told to “make no arrests but use your clubs.” The continuing importation of strikebreakers and their protection by the police eventually had their effects. The City Front Federation had brought 60 percent of the city’s business to a standstill when the unions went out on July 30. By September 20 the strikebreakers had restored the waterfront to a semblance of normal operation. Special police continued to be prominent, and a gun battle on Kearny Street involving special police brought increasing calls for the militia to restore order. Governor Henry T. Gage soon arrived in the city and met with Father Peter Yorke, a strike sympathizer whose support in 1898 Gage had considered essential to his election. The governor then brought the Draymen's officers together with union leaders but excluded representatives of the Employers’ Association. The two principals arranged a settlement within an hour, and teamsters returned to work with union buttons on their caps. During the two months of the strike, five people had died and more than three hundred had been injured.(23)

The employers claimed a victory, but in retrospect, the opposite conclusion seems unavoidable. Walter Macarthur wrote in 1906 that the “City Front Federation had vindicated the ‘right to organize.’ ” Paul Scharrenberg, more than fifty years later, saw the 1901 strike as a crucial event that “established the unions in San Francisco permanently.” According to the Employers’ Association’s own definitions, the settlement represented a defeat, or they had insisted that any agreement would amount to a surrender of their most vital principle. The Employers’ Association soon disappeared, and unions, at least briefly, had virtually an open field. One other consequence of the strike, the election of a Union Labor party mayor, guaranteed that city police powers would not again be used as they had been in 1901. Two and a half years after the strike, muckraker Ray Stannard Baker wrote that in San Francisco, “unionism holds undisputed sway.”(24)

Extension of Unionization, 1901–1916

The survival of the Teamsters and the waterfront unions, their ability to secure recognition and signed agreements governing working conditions, the disappearance of the Employers’ Association, and a sympathetic administration in city hall all contributed to a unionization surge that extended through the winter of 1903-1904. Unionization not only included the skilled trades typical of unions throughout the nation’s cities but also bootblacks, gravediggers, chorus girls, dishwashers, fish cleaners, janitors, poultry dressers, stablemen, wool sorters, and other workers who lacked unions in virtually any other part of the country. Most organized themselves into federal locals because there was no national union for their occupation. Experienced union officials warned the new unions to “go slow” and to take advantage of the moments peace and prosperity,” to prepare for worse times certain to come when economic downturn or revival of the open-shop movement might bring a crisis. Industry-wide bargaining and trade agreements became a common feature in some areas of the city’s economy, but the employer associations that developed rarely held together as well as the unions. Many, instead, were loose, informal, short-lived, and often limited to a minority of the firms in the industry.(25)

The open-shop movement came back to life in the winter of 1903–1904 when the Citizens’ Alliance formed a San Francisco branch. The Citizens’ Alliance, a national organization with branches in most major cities, attracted little initial attention in San Francisco. When Herbert George (an experienced antiunion organizer) arrived, the city’s labor movement took notice. George, a veteran of Colorado’s war on the Western Federation of Miners, found a key difference between Colorado and San Francisco. In Colorado, the state government played an active role in the suppression of the miners’ union; in San Francisco, city government paid deference to the unions, and the state government stayed out of city disputes.(26)

George undertook to build an employers’ organization in the vacuum left by the demise of the Employers’ Association, and he found eager recruits in some of the defunct association’s most active supporters. The Citizens’ Alliance attempted to use proven union weapons against the unions: it developed an open-shop label for its members to use on their printing, urged members to boycott union-label products, and picketed union shops with placards demanding the open shop. The group made frequent use of injunctions against picketing and hired private guards to protect nonunion workers. Through such tactics, the alliance did post a few victories. It broke the Stablemen’s Union and established the open shop in stables, helped to break a strike by leather workers, and enforced the open shop in retail meat markets. The open-shop campaign failed to make much other headway, however, and most city unions maintained their previous status. In 1905, the alliance focused on the restaurant industry, and the culinary unions lost a number of union-shop agreements and eventually found themselves restricted to small working-class eating houses. In the 1905 election, George and the Citizens’ Alliance made an effort to defeat the city’s Union Labor party mayor, but he won even more decisively than before. In the aftermath of the earthquake and fire in April 1906, the Citizens’ Alliance rapidly receded from the public eye. By 1907, the group still represented employers in a dozen industries, but George had been replaced, and the organization acquired a more low-key profile.(27)

These three efforts at uniting city employers had all strongly stressed that they did not oppose unions per se. The pattern began with the Manufacturers’ and Employers’ Association in 1891, which defined itself as opposed only to the unions’ “arbitrary spirit” and to strikes and boycotts. “The boycott,” they claimed, “is a crying evil of our times.” They pointed to business agents who had been bribed (presumably by businessmen) to institute boycotts of “competitors.” The Employers’ Association in 1901 publicized the following description of their principles:

We recognize the right of labor to organize to ameliorate its conditions, and we as employers will not trespass upon that right by refusing employment to anyone solely because he does or does not belong to any labor organization.

The Citizens' Alliance proclaimed a similar commitment, promising that “so long as the Union remains within legal rights it will find the Citizens' Alliance friendly.” Recognizing that “the public at large, and in fact many of our own members" mistakenly believed the alliance intended to “disrupt and destroy labor Unions,” they insisted instead that “our policy is embodied in the expression OPEN SHOP, which means that every man has the right to work and to the protection of the law." Acknowledging that “public opinion always has and will always support the Unions when they demand what is right,” the alliance added that “when through violence, an attempt is made to secure that to which they are not entitled, the Citizens’ Alliance will exert its full strength and power to defend those who are attacked, whether employers or employees." The Citizens' Alliance emblazoned these two central objectives on their letterhead as “Law and Order" and “Industrial Peace.”(28) “The open shop" and “law and order” would remain the rallying cries for employers' associations from 1901 through 1934.

Unions, of course, responded to these arguments by questioning the employers’ actual commitment to unionization. In 1908, the Labor Clarion quoted the definition of the open shop offered by Mr. Dooley, the fictional saloonkeeper created by Finley Peter Dunne, the most widely read political satirist of the day:

Whut is th' open shop? Share, ’tis a shop where they keep th' dure open t’ accommodate th' constant sthream of min coinin' in t’ take jobs cheaper thin th’ min what has th'jobs.

Andrew Gallagher, president of the Labor Council, defended the union shop in direct terms in 1914:

We as workers don't believe that the employer has any right to ask us to work alongside of the man who bears none of our burdens, who shares none of our troubles, who will take upon himself none of the duty of enforcing any of the ideals that we stand for. ... If he comes among us and refuses to become one of us, we reserve the right to cease work with him if necessary.(29)

Most unionists understood the call for the open shop as an assault on union power to enforce work rules or as an attempt to guarantee that some workers would remain on the job in the event of a strike. Professions of regard for unions fell especially flat on the ears of the veterans of 1891–1892 or 1901. Most unionists probably would have agreed with Mr. Dooley’s oft-repeated analysis:

“But,” said Mr. Hennessey, “these open shop min ye minshun say they are for the unions if properly conducted.”

“Shure,” said Mr. Dooley, “if properly conducted. An’ there ye are. An’ how wud they have them conducted? No strikes; no rules, no contracts; no scales; barely any wages, an’ dam few mimbers.”

Unions denied the predictable charges that they had incited violence and lawlessness, although Gallagher did acknowledge that the use of strikebreakers caused problems; “We are very often met on our side with over-anxious sympathizers. Sometimes they are union men and sometimes they are not.” John O’Connell, secretary of the Labor Council, denied that unionists were any more violent than employers, but noted in 1901: “If a dog got run over in the middle of Market Street the teamster would be blamed for killing him.” O’Connell flatly denied that the teamsters were responsible for violence in 1901, attributing the violence instead to “the thugs, the gunmen of the employers’ association.”(30)

Labor’s City, 1906–1916

Both “the open shop” and “law and order” took a back seat among businessmen after the earthquake and fire of April 1906. In the rush to rebuild, many San Francisco employers agreed to wage increases and improvements in working conditions as a necessary part of maintaining and expanding their work forces.(31) By one estimate, union wage scales advanced 20 percent in the year following the earthquake. There were, however, a number of union reverses after 1906 as well. Although the BTC saw its affiliates’ membership nearly double, some unions did not survive the destruction of 1906 at all because some factories were not rebuilt or union members were scattered to new places of employment.(32) Despite gains among construction unions, the membership of Labor Council affiliates remained steady.

The half-dozen years after the earthquake also saw several employers undertake antiunion drives, albeit without material support from any city-wide coalition. The most notable, the 1907 strike against the United Railroads, which ran nearly all the city’s streetcar lines, brought strong and united support for the Carmen’s Union from all parts of the labor movement including the BTC. Between May 1907 and March 1908, six men died of gunshot wounds, twenty-five people were killed in streetcar accidents, and more than a thousand were injured in accidents or in incidents between strikers and strikebreakers. In the end, the union acknowledged a defeat and turned in its charter. A much shorter and less violent strike against the Pacific Telephone and Telegraph Company brought a similar defeat for that union. The unions of the city also suffered embarrassment beginning in late 1906 and continuing for the next four years when the city’s newspapers carried report after report of graft and corruption among the labor party officeholders elected in 1905. Patrick McCarthy himself ran for mayor in 1907 but lost. He came back to win the office in 1909. The years from 1907 to the outbreak of war in Europe brought stable times for the city’s labor movement with few major conflicts and no strong open-shop campaign among the city’s employers.(33)

By World War I, San Francisco had acquired a reputation as the most unionized city in the nation: a “closed-shop city.” Despite the union shops established by the BTC, the SUP, Teamsters, culinary workers, and others, the city did not deserve its “closed-shop” reputation. Many sectors of the economy remained only partially organized, and others totally lacked unionization. While the BTC, Molders, SUP, and a few other unions may have included all—or nearly all—those in that trade as members, other unions had difficulty in organizing more than a small part of their potential membership. The culinary workers had a union-shop agreement with some restaurant owners, but many restaurants were not party to the agreement.

Three culinary unions had varying degrees of success in recruiting members in 1910.(34)

| Census count of white and black workers in the city |

Total union membership |

Percentage of white and black workers in union | |

| Bartenders | 2,177 | 681 | 31.3 |

| Waiters | 2,828 | 1,215 | 43.0 |

| Waitresses | 945 | 447 | 47.3 |

Even in the construction industry, two contractors remained immune to the power of the BTC and used only nonunion labor. Entire sectors of the city's work force lacked representation on the rolls of unions, notably office and clerical workers. Of some four thousand women employed as stenographers and typists, only ten or so were union members in 1912, and they worked in union offices or in establishments with a union shop rule. The other ninety members of the Office Employees’ Union were men, and they represented fewer than 1 percent of the male office and clerical workers in the city. Nearly all white-collar occupations lacked unions, and the few that did exist—actors, hospital stewards and nurses, draftsmen—struggled to keep their small memberships. Among public employees, only streetcar workers had organized before 1917; by mid-1919, teachers, federal employees, letter carriers, and post office clerks had also formed unions. Although unions existed for most blue-collar female workers, black and Asian workers had none. In 1910, black workers made up 0.5 percent of the total workforce. That year, the Labor Council resolved, by a narrow margin, that all affiliated unions should admit qualified black workers, but the resolution as largely symbolic. A few unions had national restrictions. Most trades had few, if any, black workers. Neither the Labor Council nor individual unions undertook major efforts to organize the few black workers in the city. The culinary unions led an effort, also in 1910, to reverse the longstanding prohibition on recruitment of Asian workers, but they lost overwhelmingly.(35)

The Law and Order Committee, 1916

San Francisco business leaders, from the earthquake of 1906 through World War I, had other priorities than confrontation with unions. As reconstruction of the city proceeded apace, the Panama Canal seized the imagination of many. Described by one booster as “the most important geographical fact since the discovery of America,” the canal seemed to pose “imperial possibilities” for San Francisco, prompting one business leader to predict that “before the end of the twentieth century San Francisco shall have superseded New York as the imperial city of America.” The bankers’ journal discerned but one cloud on this boundless horizon: “the possibility of a labor war, with the open shop as an issue, in this the most strongly unionized city in the country.”(36)

Conflict seemed imminent in 1914 when a group of businessmen formed a Merchants’ and Manufacturers Association that absorbed the remnants of the Citizens’ Alliance. No open-shop drive was launched that year or in 1915, however, due to fears for the success of the Panama Pacific International Exposition. Most business leaders saw the exposition as crucial to attracting new manufacturing and developing a tourist industry. In mid-1916, however, the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce, the city’s leading business organization, undertook an antiunion drive. Though interrupted briefly by World War I, this campaign ultimately destroyed many of the city’s most potent unions.(37)

Frederick Koster, a key person in the formation of the Merchants’ and Manufacturers’ Association in 1914, became president of the Chamber of Commerce in May 1916, just as the economic impact of the war in Europe was becoming more and more apparent. High demand for American goods, a relative shortage of labor, and rising prices all combined to encourage unions to make wage and hour demands. June 1 marked the beginning of a coastwide strike by the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA). On June 22, the Chamber of Commerce resolved that the strike constituted “an unwarranted coast-wide combination and effort to interfere with the commerce of the Port of San Francisco,” charged the ILA with “indirect and unlawful . . . enforcement of closed shop conditions,” and castigated the union for its “spirit of ruthlessness” against “helpless” shipowners. Denying any opposition to organized labor, the Chamber insisted on “the maintenance of law and order in labor disputes” and on “the right to employ union or non-union workers, in whole or in part, as the parties involved may elect.” The Chamber pledged “its entire organization and the resources it represents” to the open shop and the defense of law and order and served notice that it would oppose “any effort ... to throttle the commercial freedom of San Francisco.” Soon after, Koster and a Chamber delegation asked Mayor James Rolph to hire five hundred special policemen for the waterfront; Rolph instead ordered the regular police to search all strikebreakers for concealed weapons. Koster thereupon called a special meeting of all city businessmen, and, by the Chamber’s count, two thousand responded.(38)

Koster addressed this crowd, asking them for action to eradicate “that disease permeating this community.” He denied that the Chamber had any intention of destroying labor unions and claimed that the “law abiding union man of the most radical type” need not fear the Chamber “in the slightest.” Contrasting the “immediate selfish interest” displayed by some unions to the “communities [sic] interest,” he called for a campaign to defend not just “capitalistic industrial San Francisco” but also “the rights of the man who wants to work.” The assembled businessmen adopted a series of resolutions supporting the sanctity of contracts, the maintenance of law and order, and the open shop; created a five-person Law and Order Committee; and pledged themselves “to support this movement to the fullest extent.” The group pledged §200,000 in five minutes, and the committee raised $1 million in a few weeks.(39)

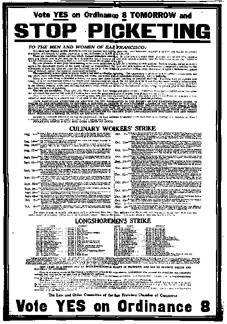

From July 1916 until April 1917, the Law and Order Committee dominated industrial relations in San Francisco, raising the hue and cry against radical unionists following the bombing of the city’s Preparedness Day parade on July 22, assisting the Restaurant Men’s Association in breaking a strike by the culinary workers’ unions, establishing the open shop in retail lumberyards, and securing passage of a strict antipicketing initiative in November 1916. The committee hired four hundred telephone operators to call every voter in the city and urge support for the ordinance. Thereafter, picketing of any sort became illegal, punishable by fifty days in jail.(40)

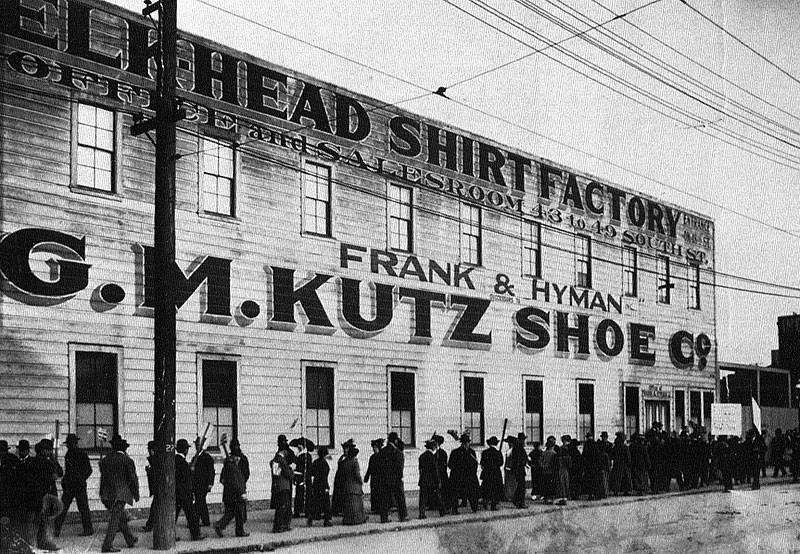

Orderly 1915 picket line at shoe factory from the Chamber of Commerce files.

Photo: California Historical Society

Notes

15. Cross, A History of the Labor Movement in California, pp. 20-21; “The California Letters of Edward Hotchkiss,” Quarterly of the California Historical Society 10 (1933):99.

16. There are four full-scale treatments of either the Sailors’ Union of the Pacific (SUP) or Andrew Furuseth, its longtime leader. See Paul S. Taylor, The Sailors' Union of the Pacific (New York, 1923); Weintraub, Andrew Furuseth; Gill and Dombroff, “History of the Sailors’ Union,” and Scharrenberg, “History of the Sailors’ Union of the Pacific.” Another history of the SUP is in preparation by Stephen Schwartz. Other important material is to be found in the Paul Scharrenberg Manuscript Collection and in that of Walter Macarthur, both at the Bancroft Library. The Coast Seamens Journal, available at the Bancroft Library, is an important chronicle of the union’s development. See also Scharrenbergs testimony before the U.S. Commission on Industrial Relations, Final Report and Testimony, 5:5043. Information on the SUP and other sea-faring unions is also to be found in Robert Coleman Francis, “A History of Labor on the San Francisco Waterfront,” Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, 1934; and in Cross, A History of the Labor Movement in California, pp. 132-133, 168-69. For a brief description of the “shape-up,” see Lawrence M. Kahn, “Unions and Internal Labor Markets: The Case of the San Francisco Longshoremen,” Labor History 21 (Summer 1980):372-373.

17. Weintraub, Furuseth; Scharrenberg and Macarthur manuscript collections, Bancroft Library.

18. For longshoremen’s organizations, see Francis, “A History of Labor on the San Francisco Waterfront,” esp. pp. 16, 32—33, 58, 65 — 66,85 — 88, 133 — 134, 144 — 148, 181 — 182. For the various councils, see ibid., pp. 65 — 66, 131 — 132, 140, 149-150; and George Charles Jensen, "The City Front Federation of San Francisco: A Study in Labor Organization,” master’s thesis, University of California, Berkeley, 1912, esp. pp. 17 — 22, 29 — 62; Gill and Dombroff, “History of the Sailors’ Union,” pp. 313 — 311, 338 — 369; Cross, A History of the Labor Movement in California, pp. 183, 198, 203, 207, 339; Knight, Industrial Relations, pp. 28, 61, 173, 272; John Kean, "City Front Federation,” Labor Clarion, Nov. 11, 1904, p. 22; John Kean, “The City Front Federation,” ibid., Jan. 19, 1906, pp. 1-3, 10; “Riggers and Stevedores," ibid., July 2, 1920, p. 10; “City Front Federation of the Port of San Francisco” file, San Francisco Labor Council Manuscript Collection, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

19. The strike of 1901 has been described many times. Knight, Industrial Relations, pp. 58 — 95, esp. pp. 60 — 67; Cross, A History of the Labor Movement in California, pp. 239 — 249; Robinson, “San Francisco Teamsters," pp. 64 — 66; Thomas Walker Page, “The San Francisco Labor Movement in 1901,” Political Science Quarterly 17 (1902):664-688, esp. pp. 668-669; Ed R. Rosenberg, “The San Francisco Strikes of 1901,” American Federationist 9 (Jan. 1902): 15-18; Jules Tygiel, “Workingmen in San Francisco, 1880-1901,” Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, 1977, ch. 6.

20. Cross, A History of the Labor Movement in California, p. 242; Knight, Industrial Relations, pp. 67—77; Page, "San Francisco Labor Movement in 1901," pp. 676—678; Robinson, “San Francisco Teamsters,” pp. 66 — 68, 145 — 148.

21. Knight, Industrial Relations, pp. 77-84; Robinson, “San Francisco Teamsters,” p. 150; Bernard Cornelius Cronin, Father Yorke and the Labor Movement in San Francisco, 1900-1910 (Washington, D.C., 1943), pp. 48-70; esp. pp. 65-66. For the analysis of the labor leaders, see Walter Macarthur, “San Francisco—A Climax in Civics,” typed manuscript, 1906, Macarthur Manuscript Collection, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, carton 1, in which Macarthur writes:

In only one particular did the situation of 1900 differ from that of 1890, namely, in the knowledge of the events that had transpired between these dates. That knowledge led to suspicion and distrust concerning the attitude of the employers . . . the defensive features of the movement, as conducted by the older men, were based upon a justifiable presumption of the opponents’ object. This difference in the particulars of the situation in 1900, as compared with that of 1890, is important as an explanation of much that transpired, (pp. 7-8)

22. Knight, Industrial Relations, pp. 78 — 80, 82 — 83; Robinson, “San Francisco Teamsters,” pp. 45 — 150.

23. Knight, Industrial Relations, pp. 84 — 86; Cronin, Father Yorke, pp. 55 — 85, esp. p. 63; Page, “San Francisco Labor Movement in 1901,” pp. 679, 685 — 687; Robinson, “San Francisco Teamsters,” pp. 150 —152; Joseph S. Brusher, S. J., Consecrated Thunderbolt: Father Yorke of San Francisco (Hawthorne, NJ., 1973), ch. 5.

24. Page, “San Francisco Labor Movement in 1901," pp. 686 — 688; Macarthur, “Climax in Civics,” p. 13; Paul Scharrenberg. “Reminiscences,” transcript of an interview in 1954 for the Bancroft Library Oral History Project, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, p. 53; Ray Stannard Baker, “A Corner in Labor: What Is Happening in San Francisco Where Unionism Holds Undisputed Sway,” McClures 22 (Feb. 1904) 366-378.

25. Knight, Industrial Relations, pp. 96 — 138, 150; “List of Trade Unions,” Labor Clarion, June 17, 1904, p. 14.

26. Knight, Industrial Relations, pp. 140—143; for George's career in Colorado, see George C. Suggs, Colorado's War on Militant Unionism: Janies H. Peabody and the Western Federation of Miners (Detroit, 1972).

27. Knight, Industrial Relations, pp. 131, 136, 139 —166, 290 —291; “Citizens’ Alliance” file, carton 6, Labor Council Manuscript Collection, Bancroft Library; “A Few of the Things Done by the Citizens' Alliance of San Francisco” (San Francisco, n.d.), a pamphlet in the Bancroft Library, University of California. Berkeley; the constitution and bylaws of the Citizens' Alliance, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley; Herbert George to George C. Pardee, Oct. 25, 1904, George C. Pardee Manuscript Collection. Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley; letter to members, Dec. 9, 1907, box 37, James Duval Phelan Papers, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley; “Citizens’ Alliance Promise and Performance,” Labor Clarion, Aug. 19. 1904. pp. 3, 8; “Citizens’ Alliance Annual Report,” ibid., Feb. 26, 1909, p. 8; “A ‘Liberal’ Citizens' Alliance,” ibid., March 31, 1911, p. 3.

28. Knight, Industrial Relations, p. 29; Cross, A History of the Labor Movement in California, p. 214; Cronin, Father Yorke, p. 50; letter to members, Dec. 9, 1907, box 37, Phelan Papers, Bancroft Library; Pierre Beringer to “Dear Sir,” Dec. 11, 1911, “Citizens' Alliance” file, carton 10, Labor Council Manuscript Collection, Bancroft Library.

29. Labor Clarion, Aug. 7, 1908, p. 3; Andrew Gallagher testimony, U.S. Commission on Industrial Relations, Final Report and Testimony, 6:5448 — 5449.

30. Michael Kazin, “Personal Management and Labor in the Early 1920s: The Case of San Francisco,” seminar paper, Stanford University, 1977, p. 12; John O’Connell testimony, U.S. Commission on Industrial Relations, Final Report and Testimony, 6:5281—5282.

31. Kahn, Imperial San Francisco, chs. 4, 7, 8.

32. Kazin, “Barons of Labor,” pp. 274—275; Knight, Industrial Relations, pp. 175-179.

33. Knight. Industrial Relations, pp. 167-298; “Organized Labor Unites to Finance the Strikes,” Labor Clarion, June 14, 1907, p. 1.

34. For census data, see Table 8, “Total Males and Females 10 Years of Age and over Engaged in Selected Occupations, Classified by Age Periods and Color and Race, Nativity, and Parentage, for Cities of 100,000 Inhabitants or More: 1910,” U.S. Bureau of the Census, Department of Commerce and Labor, Thirteenth Census of the United States: 1910, 11 vols. (Washington, D.C., 1914), 4:600-601; for the culinary union membership figures, see “Hotel and Restaurant Employees” file, Labor Council Manuscript Collection, Bancroft Library, which includes data on monthly per capita dues from Sept. 1909 through April 1910.

35 For the extent of unionization among office workers, see Lillian R. Matthews, Women in Trade Unions in San Francisco, University of California Publications in Economics, vol. 3 (Berkeley, 1913), p. 73, and also pp. 53-64,84-86. For public employees’ unions, see Labor Clarion, July 4, 1919, p. 2; for teachers, see Harriet Talan, “San Francisco Federation of Teachers, 1919-1949," master’s thesis, San Francisco State University, 1982, pp. 9-16. For general information on the extent of unionization among women in San Francisco, see Matthews, Women in Trade Unions; Jessica Peixotto, “Women of California as Trade Unionists," Publications of the Association of Collegiate Alumnae 3 (Dec. 1908):40-49; and Harriet Talan, “The Female Labor Force in San Francisco at the Turn of the Century: Some Features of Its Impulse Toward Trade Unionism,” independent study paper, San Francisco State University, 1978. For blacks, see Table 8, cited above, and also Knight, Industrial Relations, pp. 79, 88, 144, 213. For one of the best-known racial restrictions by a national union, that of the machinists, see Mark Perlman, The Machinists: A New Study in American Trade Unionism (Cambridge, Mass., 1961), pp. 16 — 17, 277—280. For Asian workers, see Table 8 cited above; Cross, A History of the Labor Movement in California, pp. 130 — 142, 147, 169—174; Saxton, Indispensable Enemy, pp. 73 — 75, 213—218, 245—253; Matthews, Women in Trade Unions, pp. 34 — 36, 95 — 100; Eaves, A History of California Labor Legislation, chs. 3 — 8, 18; Lucile Eaves, "Labor Day in San Francisco and How Attained," Labor Clarion, Sept. 2, 1910, p. 6. The culinary workers did not take their defeat on the issue of organizing Asian workers as final, and in 1916 they announced their intention to organize Japanese culinary workers; see Labor Clarion, Aug. 18, 1916, p. 10.

36. Chamber of Commerce Journal, Dec. 1911, esp. pp. 1, 5; Coast Banker, March 1911, p. 200. See also Chamber of Commerce Journal, Feb. 1912, p. 12; ibid., Nov. 1912, p. 1.

37. Knight, Industrial Relations, pp. 249 — 250, 290—298, 329.

38. San Francisco Chamber of Commerce Activities, June 22, 1916, p. 1; ibid., July 13, 1916, pp. 1, 3 — 5; San Francisco Chamber of Commerce, Law and Order in San Francisco: A Beginning (San Francisco, 1916), pp. 1-19; Knight, Industrial Relations, pp. 300 — 307.

39. Chamber of Commerce, Law and Order, pp. 1—19; Knight, Industrial Relations, pp. 300-307.

40. Knight, Industrial Relations, pp. 309-336, 346-350; Chamber of Commerce, Law and Order, pp. 20 — 37; Chamber of Commerce Activities, Sept. 7, 1916, pp. 1-3; Curt Gentry, Frame-Up: The Incredible Case of Tom Mooney and Warren Billings (New York, 1967).

Excerpted from San Francisco 1865-1932, Chapter 4 “Unions and Employers”