Native American Health Center: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

m (Center not Clinic) |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

[[Image:Addressing-injustice.png|left]] | [[Image:Addressing-injustice.png|left]] | ||

{| style="color: black; background-color: #F5DA81;" | {| style="color: black; background-color: #F5DA81;" | ||

| colspan="2" | '''For centuries, Native Americans have resisted genocide and culturaldestruction. Healthcare is one important front of indigenous struggles for dignity and self-determination. The history of the Native American Health | | colspan="2" | '''For centuries, Native Americans have resisted genocide and culturaldestruction. Healthcare is one important front of indigenous struggles for dignity and self-determination. The history of the Native American Health Center (NAHC) in the San Francisco Bay Area offer a window into the complex challenges of sustaining traditional ways and integrating them with Euro-American health practices. This article explores the history of the NAHC.''' | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

Briggs, Charles L. “Communicability, Racial Discourse, and Disease.” Department of Anthropology, UC Berkeley. 2005. Scholarly Article. <br> | Briggs, Charles L. “Communicability, Racial Discourse, and Disease.” Department of Anthropology, UC Berkeley. 2005. Scholarly Article. <br> | ||

Canales, Mary, Weiner, Diane. “‘It Is Not Just Diabetes’: Engaging Ethnographic Voices to Develop Culturally Appropriate Health Promotion Efforts.” ''American Indian Culture and Research Journal'', volume 38 issue 1 p. 73. 2014. <br> | Canales, Mary, Weiner, Diane. “‘It Is Not Just Diabetes’: Engaging Ethnographic Voices to Develop Culturally Appropriate Health Promotion Efforts.” ''American Indian Culture and Research Journal'', volume 38 issue 1 p. 73. 2014. <br> | ||

Cummings, Courtney. 2 March 2015. Location: Native American Health | Cummings, Courtney. 2 March 2015. Location: Native American Health Center (NAHC), Richmond. Interview. <br> | ||

[http://www.nativehealth.org/content/history-background “History and Background.”] Native American Health Center. Web. <br> | [http://www.nativehealth.org/content/history-background “History and Background.”] Native American Health Center. Web. <br> | ||

King, Janet. 13 March 2015. Location: Native American Health Center, Oakland. Interview.<br> | King, Janet. 13 March 2015. Location: Native American Health Center, Oakland. Interview.<br> | ||

Revision as of 16:49, 17 May 2021

Historical Essay

by Jacob Penny, 2015

| For centuries, Native Americans have resisted genocide and culturaldestruction. Healthcare is one important front of indigenous struggles for dignity and self-determination. The history of the Native American Health Center (NAHC) in the San Francisco Bay Area offer a window into the complex challenges of sustaining traditional ways and integrating them with Euro-American health practices. This article explores the history of the NAHC. |

In 1972, the Native American Health Center (NAHC) was opened in San Francisco on 56 Julian Avenue to provide accessible, culturally competent health services to Native Americans. Many of the Native American founders of the clinic and many of the Native American patients who utilized the clinic lived in the San Francisco Bay Area as a result of the Federal government’s relocation programs promulgated in the 1950s and 60s—see Indian Relocation Act of 1956. From its origins, NAHC sought to integrate Euro-American style medical, dental, and mental health services with traditional indigenous health care in an effort to create holistic care that was effective and appropriate for its community. NAHC states on their website: “It’s more palatable for a middle-aged, American Indian man to attend drum practice than it is for them to come in and receive counseling on weight management or smoking cessation.” Some of the traditional ceremonies they facilitate include: the Wiping of the Tears, baby naming ceremonies, and traditional art classes. Offering such ceremonies facilitates community building and cultural healing in a way that mainstream, American biomedicine cannot. In this respect, the work of NAHC takes holistic account of how centuries of genocide with the destruction of traditional foodways & diet, language, ceremony, and lands are linked to contemporary health and mental health epidemics for Native Americans.

While the factors leading to the need for the creation of NAHC should be traced back to the first contact with Euro-Americans in the mid 1500s, the idea to create the Center was first explicitly discussed during the occupation of Alcatraz Island, which began on November 9,1969 and lasted until June 11th, 1971. During the historic occupation, Native Americans created extensive systems of community care. Dr. Greg Goddard, DDS provided free dental services to the children on Alcatraz during its occupation. By its end, a group of people participating in and supporting the occupation, noticing Native health problems, decided to come together to create a space where they felt secure in going for reasons of health. This culminated in the 1972 opening of NAHC.

In the initial years between 1972 and 1979 the leaders of the NAHC attempted to create a deeply community-rooted Center that was financially sustainable. Community needs were assessed to determine how to best structure the Center and most effectively provide care. This involved extensive research and strategic cooperative planning. Day-to-day survival was a large focus of attention in the chaos of standardizing procedures and practices in order to maintain legal status as a health care provider. These challenges reveal the central dilemma of organizing a health center around principles of indigenous collective community care when the broader, prevailing paradigm is for-profit health care.

During the 1980s, the NAHC was building its identity and reputation within the community. This decade, characterized by cuts to State programs, presented additional barriers to success. Almost 90% of the budget through this decade was from the Federal Indian Health Service (IHS). One factor contributing to scarcity of funding was that Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) status would not be achieved until the 1990s. Throughout the 1980s, there was a sense that they were in a financial hole that could not be overcome. At times this meant that staff were not paid in a timely manner for their work.

Marin “Marty” Waukazoo became the CEO of the NAHC in 1982. Waukazoobegan to establish new organizational structures. He remains the CEO, and in his time since 1982, the annual budget has ballooned from $800,000 to $23 million.

In the 1990s, the future of the NAHC became more certain as FQHC status and funding became successfully secured. The annual budget by 1995 had grown to just under $4 million. The greater financial support meant that they were able to afford establishing a reserve account and, for the first time, insurance for the Center. It also allowed for greater hiring of staff but presented the problem of finding potential staff with the correct skills and talent that would translate into the most effective operation. In time, the first staff for human resources was hired. Despite these successes, in the mid 90s, the board of directors attempted to fire Waukazoo. However, staff and community support for him as the CEO effectively blocked this action.

The NAHC has become an established healthcare organization that provides care to a population that has been systematically persecuted and massacred, both physically and culturally. They have been successful in this goal and have established themselves as a key as a part of the Bay Area Native community in post/neo-colonial America. They currently employ over 250 individuals and have offices in San Francisco, Oakland, Alameda, and Richmond.

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/JanetKingMSWNativeAmericanHealthCenter" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Video by Jacob Penny

Colonization, a complex, multifaceted process of structural violence, had, and still has, significant impacts on every aspect of indigenous people in California. The common phrase which was iconic of this harmful perspective was “kill the Indian and save the man.” However, it was found that culture was not easily washed away from older generations, which resulted in the creation of programs that would remove younger generations from their traditional culture and instill them with White American culture vis-à-vis boarding schools. This removal from the complex cultural systems into traumatic environments devoid of role models and loving parenting figures enabled mental illness and lack of knowledge on how to care for family and other loved ones.

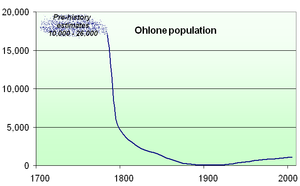

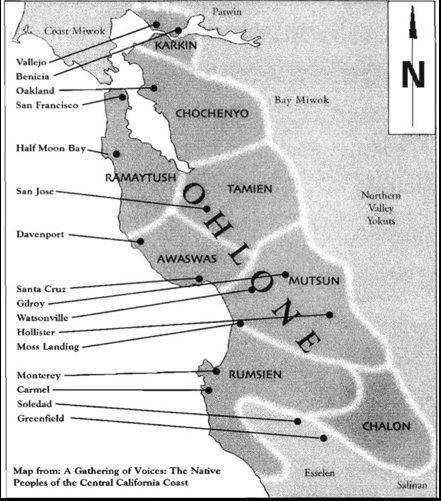

On another front, the disappearance of traditional indigenous sources of sustenance was another way in which cultural lifeways were being systematically eliminated. Euro-American exploitation of land to farm and raise livestock as well as unsustainably hunt for sport created an imbalance in the ecosystem that resulted in steep reductions in local animal and plant populations and diversity, and extinction in some cases. One tribe that is exemplary of this form of genocide is the Ohlone, or Costanoan, which included multiple language groups and whose territory extends from the modern day San Francisco area to Santa Cruz and south to Salinas Valley. Their diet was varied and included bugs, plants, small and large mammals, reptiles, birds, and fish. The claiming of space which was traditionally Ohlone territory for herds of cattle drove some villages to near starvation through the lack of sufficient territory for food collection and the disruption of native species and sophisticated conservation strategies such as field burning.

Bibliography

Adair, Deuschle. “The People’s Health: Medicine and Anthropology in a Navajo Community.” Meredith Corporation 1970. Book.

Bastos, Cristiana. "Medical Hybridisms And Social Boundaries: Aspects Of Portuguese Colonialism In Africa And India In The Nineteenth Century." Journal Of Southern African Studies, 33.4 (2007): 767-782.

“Board.” Community Health Center Network.Web.

Briggs, Charles L. “Communicability, Racial Discourse, and Disease.” Department of Anthropology, UC Berkeley. 2005. Scholarly Article.

Canales, Mary, Weiner, Diane. “‘It Is Not Just Diabetes’: Engaging Ethnographic Voices to Develop Culturally Appropriate Health Promotion Efforts.” American Indian Culture and Research Journal, volume 38 issue 1 p. 73. 2014.

Cummings, Courtney. 2 March 2015. Location: Native American Health Center (NAHC), Richmond. Interview.

“History and Background.” Native American Health Center. Web.

King, Janet. 13 March 2015. Location: Native American Health Center, Oakland. Interview.

King, Janet, Martinez, Martha. Native American Health Center: 7 Generations 1 Direction. Retrieved from powerpoint notes.

Shawnego, Michelle. “NAHC Timeline.” 2015. Document.

Wiedman, Dennis. “Native American Embodiment of the Chronicles of Modernity.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly, Vol. 26, Issue 4, pp. 595–612, ISSN 0745- 5194, online ISSN 1548-1387. 2012 by the American Anthropological Association.

Nebelkopf and Phillips. “Healing and Mental Health for Native Americans: Speaking in Red.” AltaMira Press. 2004. Book.

Norris, Vines, and Hoeffel. “The American Indian and Alaskan Native Population: 2010.” (pdf) 2010 Census Brief. Online.

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. “Broken Promises: Evaluating the Native American Health Care System.” September 2004. Book.