Margo St. James: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

''—Margo St. James, Montpeyroux, France, August 1988'' | ''—Margo St. James, Montpeyroux, France, August 1988'' | ||

[[Image:Gallery xlarge 002.jpg|800px]] | |||

'''Margo St. James, 1980''' | |||

''Photo: John O'Hara/SF Chronicle'' | |||

[[category:Women]] [[category:Famous characters]] [[category:Marin County]] [[category:crime]] [[category:1970s]] [[category:1980s]] [[category:2020s]] [[category:Tenderloin]] [[category:Visitacion Valley]] [[category:Downtown]] | [[category:Women]] [[category:Famous characters]] [[category:Marin County]] [[category:crime]] [[category:1970s]] [[category:1980s]] [[category:2020s]] [[category:Tenderloin]] [[category:Visitacion Valley]] [[category:Downtown]] | ||

Revision as of 15:39, 14 January 2021

Unfinished History

St. James Infirmary on the Passing of Margo St. James, from Facebook, January 12, 2021

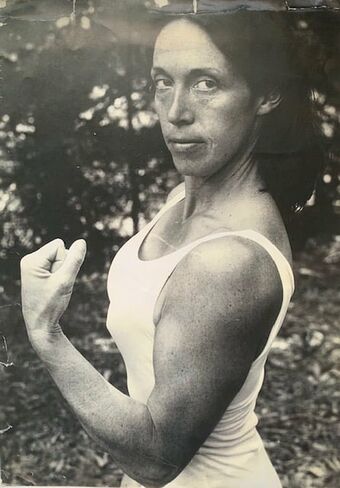

Margo St. James

Photo: St. James Infirmary

With profound sadness, the St. James Infirmary announces the death of the most storied among our founders, Margo St. James.

The St. James Infirmary is a part of Margo’s legacy. So too are her deeds and words, that exposed hypocrisy with extraordinary wit. Much can be said of Margo, but her own words offer the best testament to who she was.

From A Vindication of the Rights of Whores, by Gail Pheterson, Preface by Margo St. James:

“What’s a nice girl like you…?” was the usual reaction of men to my becoming a feminist as well as to my becoming a prostitute. The difference for me was that I chose to be a feminist, but I decided to work as a prostitute after being labeled officially by a misogynist judge in San Francisco at age twenty-five. It was 1962. I said in court, “Your Honor, I’ve never turned a trick in my life!” He responded, “Anyone who knows the language is obviously a professional.” My crime? I knew too much to be a nice girl!

My politicization occurred over a three-year period, 1970-73. I was living in Marin County, north of San Francisco, with a carpenter/musician, Roger Somers. I also socialized with the housewives who were participating in consciousness-raising groups. Elsa Gidlow, a lesbian poet, lived next door and used to push feminist literature under my door. The forerunner of COYOTE was WHO: Whores, Housewives, and Others. “Others” meant lesbians but it wasn’t being said out loud yet, even in those liberal bohemian circles. The first meeting of WHO was held in 1972 on Alan Watts’ houseboat (“The Vallejo”) is Sausalito. The name COYOTE came from the author, Tom Robbins, who dubbed me the “COYOTE Trickster” following one of our mushroom-hunting expeditions. Richard Hongisto, a liberal sheriff elected in San Francisco about that time, attended some of Roger’s and my parties. A former cop with a degree in sociology, he was recently divorced and a little afraid to let it all hang out in the City since the cops didn’t have much love for him; he preferred to party in Marin. I cornered him one night in the hot tub and asked what NOW was doing for the rights of prostitutes. Since he seemed to have the support of the women’s movement and gay rights groups. He answered, “Someone from the victim class has to speak out. That’s the only way the issue is going to be heard.”

I decided to be that someone, even though I had worked only four years, and wondered about the effect speaking out would have on my life. I received complete support from most of my family; my mother the housewife-secretary, my sister the gospel singer with eleven children, my sailor brother and my son the salmon fisherman – both with two children and wives. Together with a cadre of friends around the San Francisco Bay Area and across the United States, they convinced me that speaking out was the right thing to do. My father stopped talking to me.

In 1973 I decided to reconnect with the lawyers, bail bondsmen, journalists and cops I knew in the City ten years before and hoped some of the hookers would join me. The PR people responsible for getting the sheriff elected volunteered to help me with COYOTE. I rented a cheap hotel room on the waterfront and started collecting info by hanging around the Hall of Justice. It was easy…the same people were still working in the courts and remembered me as “the kid who got a bum rap.” I had gained some notoriety at the time of my trial because I successfully appealed the conviction, but it didn’t help me get other gainful employment.

A professor from the University of California gave me some good leads for resources, including an introduction to the treasurer of Glide Church who also handled the Whole Earth Catalog millions. The treasurer got me a personal grant for five thousand dollars. The other good score was the copy machine at the Gas and Electric Company which sat by itself in a small room on the 8th floor. During lunch hours for two years, I dressed as a secretary and ran off the material necessary to be a successful rabble-rouser.

Another longtime friend got a job as the jail doctor so I had inside information as well as gossip from the women he examined. Prostitutes were still being quarantined at the time which means you had to be examined for VD before you get out of jail. We stopped the practice the following year. Steve the Pig, as he called himself, was a beat cop who gave me the straight scoop from the streets and the cops’ locker room. A liberal mayor was elected in 1976, George Moscone, who appointed an out-of-town chief of police, much to the chagrin of the “good ole boy” cops who had run the city for fifty years, successfully keeping minorities and women from being hired on the force. The mayor and a gay supervisor, Harvey Milk, were assassinated on November 27, 1978, by former cop/supervisor Dan White. Following the murders, Moscone’s successor, Diane Feinstein, caved into cop pressure and fired the chief. The cops had felt that “the whores have the chief’s ear.” He had done much to straighten out the corruption and disorder in the department and he had transferred many of the abusive vice cops away from hooking. The climate changed and the liberals who had been supported of decriminalizing prostitution became unwilling to speak publicly about the issue. Even the sheriff backed down and claimed he never attended a Hooker’s Ball, although he attended several before 1977. It became clear that outside pressure was necessary for any gain in the movement.

I began to seriously consider organizing internationally. Manipulating the press was very important because through the exposure other women in other cities and countries were inspired to form groups. It seemed that the people necessary to make a good start were a political hooker, a feminist, a friendly journalist and a lawyer.

Jennifer James, a professor of anthropology in Seattle, was very instrumental in getting things going there and nationwide. She coined the word “decriminalization” and was responsible for NOW making decrim a plank at their 1973 convention. COYOTE published a newsletter, “COYOTE HOWLS” for five years from 1974-1979. We reported national and international news on prostitution, first-hand accounts of abuses, feminist theory and research on prostitution and poetry by prostitutes. In order to expose the hypocrisies of the prohibition on prostitution and to make our demands for human rights, medical care, and working conditions palatable for the public, we solicited hip artwork from cartoonists Robert Crumb, Trina Robbins and others to spice up our publications. We also compiled reading lists for those who wished to join the struggle and attended the major women’s conferences around the country. We ran ads for t-shirts, posters and the Hooker’s Ball which was our annual October fundraising event. The Ball became very popular, attracting 20,000 people in 1978 at the Cow Palace, grossing $210,000 (net $60,000), enough to pay five staff for our two offices (one at the waterfront and one uptown). Our mailing list exceeded 60,000 people, about three percent of whom were prostitutes.

Many non-prostitute women were instrumental in keeping the COYOTE offices functioning. Molly Rodriguez was the secretary for five years. Priscilla Alexander joined the office in 1977 and succeeded in getting NOW to form a committee on Prostitutes’ Rights in 1982 and to get most women’s conferences around the country to concretely address the issue. Priscilla and Gloria Lockett now co-direct the offices of COYOTE, U.C. CAL-PEP (California Prostitutes’ Education Project) and the National Task Force on Prostitution, concentrating on AIDS prevention and education and on human rights of prostitutes. A new development which could indicate a warming trend is that candidates for public offices now come to COYOTE for information and are willing, if elected, to carry bills to the legislature for decrim. And the best news is that, after I left the county in ’85, the government and private foundations have given grants to COYOTE!

It became increasingly clear to me following the advent of the anti-porn movement in the States that an international movement was timely and essential. I attended the 1976 International Tribunal on Crimes Against Women in Brussels and the United Nations Decade of Women Conferences in 1975 (Mexico City) and in 1980 (Copenhagen). But it wasn’t until I met Gail Peterson, who had been working in the Netherlands on bridging divisions between women, that things started coming together internationally. We organized mostly by combining our networks, especially her feminist contacts and my hooker contacts in Europe. Also, Gail spent the year of ’84 in California forming alliances between pros, ex-pros and non-pros out of which grew the Bad Girl Rap Groups hosted by COYOTE. The Women’s Forum on Prostitute’s Rights and COYOTE Convention were designed by Gail in ’84 to coincide with the Democratic Convention held in San Francisco. A Bill of Rights was born at the COYOTE Convention which became the underpinning for the First World Whore’s Congress in Amsterdam in 1985 and the Second World Whores’ Congress in Brussels in 1986.

The conservative swing in the States generally and in the woman’s movement, in particular, prompted me to move to Europe in ’85 so that I could put more energy into the International Committee. Although those wanting to abolish prostitution are more active than ever, there are politicians and women’s groups willing to stand up for prostitutes’ rights in many countries. I enter a plea of innocent for all those incarcerated for prostitution and cheer on all those who have the courage to speak out on their own behalf. Hopefully, this book will generate the kind of thinking and awareness and activism necessary to right the wrongs committed against whores for centuries.

—Margo St. James, Montpeyroux, France, August 1988

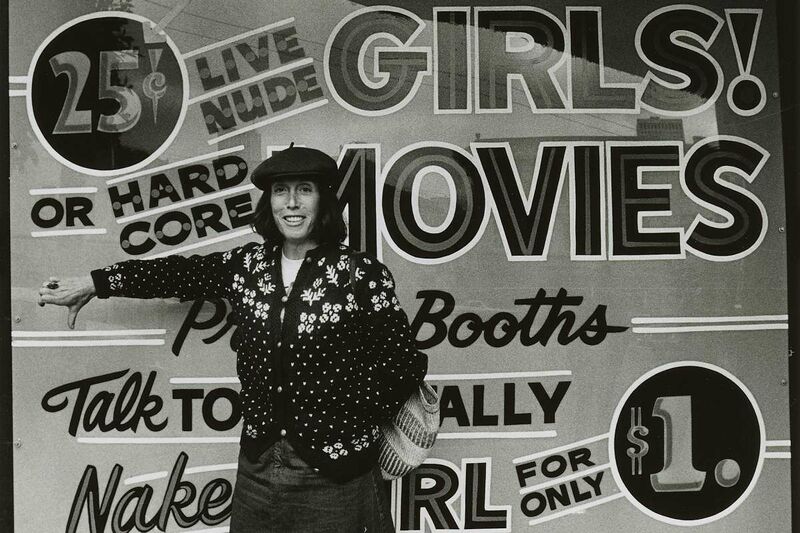

Margo St. James, 1980

Photo: John O'Hara/SF Chronicle