Ghirardelli Square: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 93: | Line 93: | ||

[[Cannery Description |Prev. Document]] [[Nature Reclaims a Piece of the Waterfront |Next Document]] | [[Cannery Description |Prev. Document]] [[Nature Reclaims a Piece of the Waterfront |Next Document]] | ||

[[category:North Beach]] [[category:1960s]] [[category:Women]] [[category:Landmarks]] [[category:Real | [[category:North Beach]] [[category:1960s]] [[category:Women]] [[category:Landmarks]] [[category:Real estate]] [[category:1990s]] [[category:1890s]] [[category:1900s]] [[category:1860s]] [[category:food]] [[category:Fisherman's Wharf]] [[category:Italian]] | ||

Revision as of 14:11, 29 May 2018

Historical Essay

by Chris Carlsson

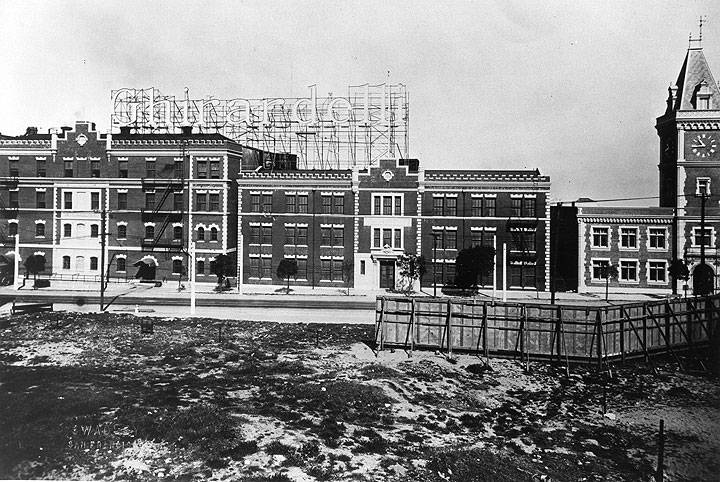

Formerly the Pioneer Woolen Mill, then the Ghirardelli Chocolate Factory, and today, the prototype for modern malls inside of historic urban structures, typically rehabilitated warehouses.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

In 1936, the area around the Ghirardelli Chocolate Factory was still "undeveloped."

Photo: Private Collection, San Francisco, CA

Ghirardelli Square is a world-famous adaptation of an old brick factory into a modern shopping mall. It happened in a particular context that took shape in the 1950s and early 1960s when San Francisco was undergoing a massive makeover, driven by a combination of public initiative and private investment. In the case of Ghirardelli Square, parts of the complex dated from the 19th century Pioneer Woolen Mill, and other structures had been part of the long-time family-owned San Francisco chocolate company.

Mustard Building, part of the Ghirardelli Square complex.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Cocoa Building.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

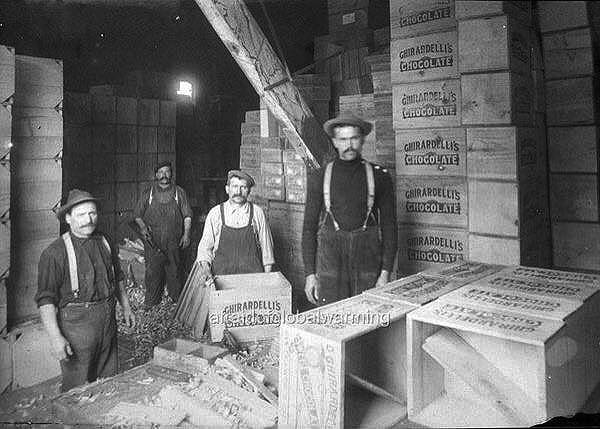

Ghirardelli workers packing chocolate, n.d.

Photo: Lily Costello via Facebook

After the Fontana Towers went up on the site of the old brick Fontana pasta factor in 1962, just to the west of Ghirardelli Square, plans were floated to tear down the chocolate factory and replace it with a modernist highrise along the same lines. Thanks to the liberal-minded shipping tycoon William Roth (whose investments in container technology had been an essential driving force in starting the deindustrialization of San Francisco) and the influence of the preservationists around Karl and Jean Kortum who had fought for the Maritime Museum along Aquatic Park as a public amenity, a different plan was hatched. Bringing in real estate managers from Sausalito who had already pioneered an adaptive re-use of an old wooden structure along its waterfront road, Roth hired Lawrence Halprin and his firm to combine new modernist elements with the historic structures to produce a uniquely new hybrid. The success of Ghirardelli Square once it opened proved the concept that quickly spread across the country and the world. In the early 21st century we take the historic preservation and adaptive re-use of old brick warehouses and factories for granted. But when Roth put his money into the innovative approach it set in motion a sea change in urban planning. It also gave a boost to the emerging California Cuisine movement, a retail food and wine phenomenon that relied on outdoor living, fresh produce, and an international blend of styles and flavors.

Just a few blocks to the east another investor got his loans when Roth’s project began moving forward. Leonard Martin grew up in China but made it his life’s passion to convert the old Del Monte Fruit Canning plant, that had been defunct since 1937, into a new shopping mall called The Cannery. By preserving the historic character of the building facades while renovating the interiors for modern retail and restaurant use, these projects solidified an approach to modernization that ultimately helped preserve hundreds of buildings, both commercial and residential, across San Francisco and give it its much-loved special character today.

Woolen Mill building.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

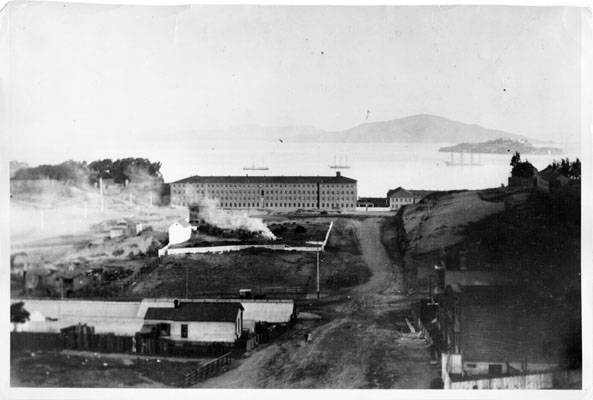

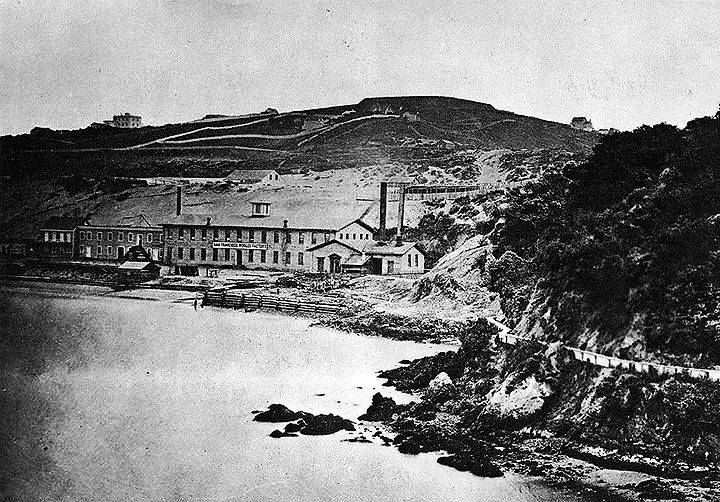

Pioneer Woolen Mills at North Beach, 1868

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

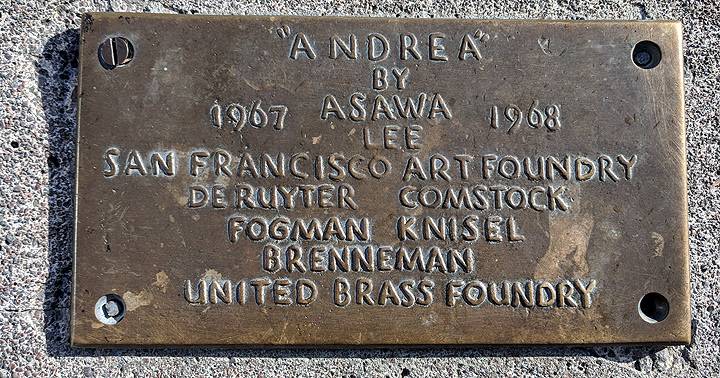

When Ghirardelli Square was nearly complete, a fountain was commissioned for the interior courtyard. As Alison Isenberg sharply describes, sculptor Ruth Asawa’s “Mermaids” sculpture

“marked an early skirmish in the emergence of second-wave feminism. Women’s liberation had not yet found the national stage of the Miss America protest in Atlantic City, feminist art theory had yet to be launched, and public art had not yet explicitly take up subjects of female sexuality from feminist perspectives. Nursing in public was a radical position, as were public representations of lesbian couples or sexual organs. The plaza’s feminist statements were effective precisely because they were clothed in the guise of a charming sculpture for families.(1)

Photos: Chris Carlsson

Lawrence Halprin, the modernist architect whose fame had grown rapidly after he designed the first glass-clad skyscraper at 1 Bush Street (at the corner of Market and Battery) that also featured an expansive sunken plaza and an innovative circular bank branch at the corner of the property, was the chief architect of Ghirardelli Square. He leaped into a very public controversy when he attacked Asawa’s sculpture as being out of character with his hybrid plaza and far too representational. He favored a 15-foot metal shaft for the fountain and that blatantly phallic preference versus the overtly feminist iconography of the Mermaids fountain led to a battle in the editorial pages of the San Francisco Chronicle that Halprin came out on the losing end of. Isenberg sums it up:

In 1968 San Franciscans saw relatively unprecedented scenes in Ghirardelli Square—breast-feeding, a lesbian family, an amphibian orgy, possibly mermaid vaginas. In trying to raise a controversy over abstraction versus representation, modern versus historical, and the sculpture’s artistic style, Halprin precipitated a public conversation about gender, sexuality, and power and their location and role in urban space, neighborhood revitalization, tourism, and the city’s future.(2)

The fact that the Mermaids sculpture became a popular cause for local feminists underscored the role of women in the new urban redevelopment process that was underway. Graphic designer Bobbie Stauffacher and public relations specialist Marion Conrad had both been employed in key roles in Ghirardelli Square, as well as other contemporaneous projects like The Sea Ranch on the Mendocino coast. Stauffacher later wrote Conrad that “We looked like career women. We felt like road kill,”(3) as they commiserated over the gender politics that surrounded them. In spite of their obvious commercial success, they still acutely felt the limitations imposed on them by the larger dynamics of a male-dominated society.

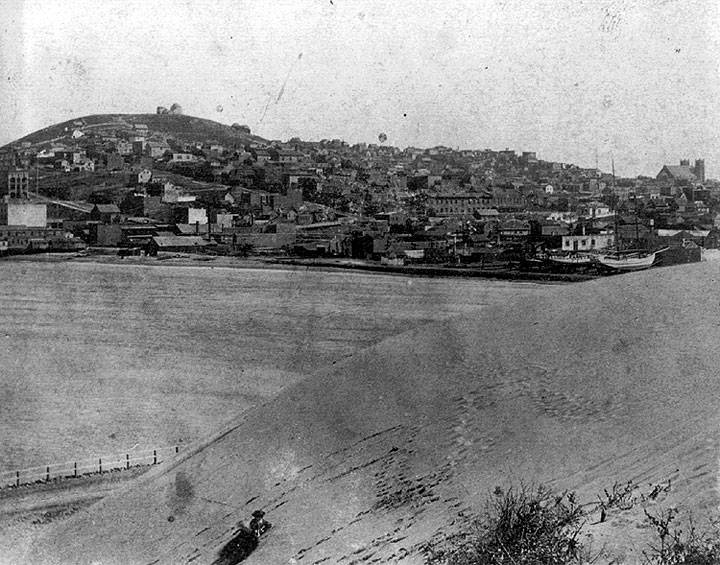

Pioneer Woolen Mills at original shoreline.

Photo: Bancroft Library

Big sand dunes on Black Point, with Telegraph Hill in distance.

Photo: Private Collection, San Francisco, CA

Notes

1. Designing San Francisco: Art, Land, and Urban Renewal in the City by the Bay, by Alison Isenberg, Princeton University Press: 2017, p. 110

2. ibid.

3. ibid. p. 227