Early History of San Francisco Library: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|

(No difference)

| |

Revision as of 12:11, 28 August 2015

Historical Essay

by Emily Strickler, 2015

Golden Gate Branch of San Francisco Public Library in Cow Hollow at 1801 Green Street, dating to 1912 when the Carnegie Endowment funded public library construction across the United States.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

When you think about San Francisco’s early years, with the 1850s forward, you probably imagine a busting yet cosmopolitan frontier town. You probably don’t imagine early San Francisco as an emerging literary city, able to compete with other large cities such as Boston and London across the world. However, by the mid-1850s, San Francisco was able to boast about having more newspapers, in more languages, than London, a flourishing book trade, and the largest number of books published west of the Mississippi. The 12 newspapers in the city employed over 1,000 people. Before the famous Beat writers of San Francisco, there were the authors of the 1850s that helped put San Francisco on the map as a literary hot spot, such as Joaquin Miller and Mark Twain. The writers of this time are commonly known for their western genre, keeping with the stereotype of San Francisco as a frontier town.

Similar to writers, libraries came early to San Francisco. The city’s first “library” was opened to guests in 1852, in a room in the “What Cheer House”, a men’s temperance hotel built by Robert B. Woodward. The library room held 2,000 to 3,000 books as well a vast newspaper collection. After this library room, the city witnessed the establishment of several private libraries. In 1853 and 1854 the Mercantile Association and Mechanics’ Institute respectively established private, subscription-based libraries. Additional private libraries were established by groups like the International Order of Odd Fellows, as well as by individual collectors such as Leland Stanford, with a 3,000 volume collection, and Hubert Howe Bancroft, with his 20,000 volume collection.(Wiley) These private libraries we’re indicative of a larger city attitude about culture. In San Francisco, and across the nation, the focus was on private enterprise, leaving public amenities to fall by the wayside. It took three decades before the idea of a public library was able to materialize.

In the 1870s, San Francisco was enduring a tumultuous time in its history leading up the introduction of the public library in the city. After the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, economic struggle struck. Unemployment numbers rose, and cheap goods flowed in. When the depression struck the east coast in 1873, workers rushed to the West coast in search of work. Simultaneously, the city’s population number was also swelling as a result of 80,000 Chinese immigrants. The influx of newcomers did not help the unemployment situation, which in turn fueled anti-Chinese sentiments, eventually instigating the Chinese Exclusion Law of 1882. Finally, the 1870s in San Francisco were plagued by the collapse of the Bank of California, as William Ralston’s pyramid schemes caused mass hysteria. Surprisingly, the idea of a public library was born out of this economic turmoil.

On August 3rd, 1877, a group of prominent San Franciscans met at Dashaway Hall to hear Senator George H. Rogers’ report of his inquiries in regard to the establishment of “free public libraries in other American and European cities.” The initiative was spearheaded by Andrew S. Hallidie, who also invented the cable car. Hallidie was served as the president of the Mechanics’ Institute, and called for a public library after frustrating attempts to convert his privately endowed library into a public institution (Wiley, 1996, p. 98). The public library has always been viewed as a contribution of upper-class liberals who wished to help the lower classes (Dumont, 1977, p.3), and the case of the San Francisco Public Library was the same. Individuals who attended the August 3rd meeting thought the library “would do more to overcome hoodlumism than the extremist rigors of the law” in addressing the city’s high unemployment rates. At the same time, some motivations behind the library were less noble. One committee member thought the library would benefit the city because “one educated boy will come nearer to rectifying the Chinese problem than a legion of rioters” (Wiley, 1996, p.98).

The Rogers Act was signed into law on March 18, 1878 and authorized any incorporated city or town to levy a tax not exceeding one mill on the dollar of assessed property, in order to start funding the public library. The act also stipulated that the library was to be governed by a self-perpetuating board of trustees in order to prevent in infiltration of corrupt city politics (Wiley, 1996, p.99). The first board of trustees was made up of George H. Rogers, Andrew S. Hallidie, Henry George, Irving M. Scott, Robert S. Tobin, E.D. Sawyer, John H. Wise, Andrew J. Moulder, Louis Sloss, and C.C Terrill, all of whom were influential and self-made business men. Despite pushes to consolidate the city’s existing libraries into a giant public library (Chronicle, Jan 10 1886), the Trustees thought it would be better to find a location that was separate and distinct for the city’s first free public library. The library opened in a large auditorium on the second floor of the Pacific Hall on Brush Street on June 7, 1879. Due to financial constraints, the majority of the books present on opening day were donated or bought on borrowed money. Unfortunately, there were so few materials that patrons could not take items out of the library.

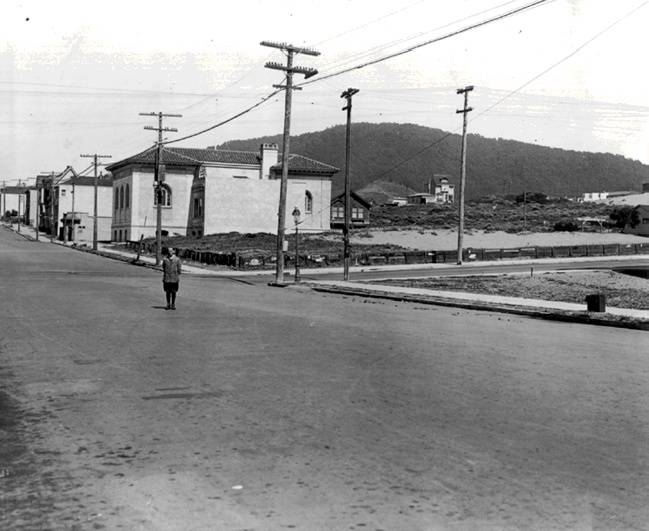

The Sunset Branch of the Public Library is at the outskirts of civilization in this 1920 photo. The intersection between the boy and the library is 19th and Irving. Jefferson Elementary School would be built later on the same block as the library branch. Sutro Forest looms in background.

Photo: Private Collection, San Francisco, CA

Library growth caused the library to move to City Hall, first to the Larkin Street wing in 1888, then again to the McAllister Street wing in 1893. The library’s success was astounding. Between June 30, 1889 and June 30, 1890 the library was able to increase it’s total volume, map, and pamphlet ownership by 7,580 items. (Board of Trustees Reports, 1890 and 1891, Appendix IV) Strangely, in this same year span, library visitor numbers dropped by 3,998 (Board of Trustees Report, 1891, Appendix I). During this period of time, in order to become a borrower, an individual had to be over the age of 12, and could either be a resident or a non-resident tax payer of the city and county. As a result of increased volume stock, rules were changed that allowed circulation materials to be taken home. There were three classes of books: books that could be issues on presentation of library card, slip, or door check, for use at home or in the library, books issues on presentation of library card, slip, or door check, by permission of the librarian, and books issued on slip and door check only, with restricted use in the library. Fines for overdue books were set at five cents per day. (Supplementary Catalogue, 1888, p.vi)

The public library was not immune to the destruction caused by the 1906 earthquake. The subsequent fires destroyed 138,000 library volumes at the Main Branch in city hall, and completely destroyed the North Beach and South of Market branches. When the earthquake struck, approximately 15,000 books were checked out, and only 1,500 of those materials found their way home. In 1981, the last book from the cohort of checked out books during the earthquake was returned. The next library was built around the remaining 25,000 books left between the remaining four branches.

Sources

DuMont, R. (1977). Reform and Reaction: The Big City Public Library in American Life. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press.

FREE PUBLIC LIBRARY. (1877, Aug 04). San Francisco Chronicle (1869-Current File) Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/365644039?accountid=14026

A GREAT LIBRARY. (1886, Jan 10). San Francisco Chronicle (1869-Current File) Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/357226722?accountid=14026

Report of the Board of Trustees of the San Francisco Free Public Library June 30, 1890. 1891. Print.

Report of the Board of Trustees of the San Francisco Free Public Library June 30, 1890. 1890. Print.

Supplementary Catalogue of Books Added to the San Francisco Free Public Library since May, 1884. No. 5, 1888. San Francisco: H.S. Crocker &, Printers, 1889. Print.

THE FREE LIBRARY. (1889, Feb 12). San Francisco Chronicle (1869-Current File) Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/357176292?accountid=14026

THE FREE LIBRARY. (1889, Apr 07). San Francisco Chronicle (1869-Current File) Retrieved

from http://search.proquest.com/docview/572173541?accountid=14026

THE FREE LIBRARY. (1880, May 05). San Francisco Chronicle (1869-Current File) Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/571869541?accountid=14026

Wiley, P. (1996). A Free Library in This City: The Illustrated History of the San Francisco Public Library. San Francisco: Weldon Owen.