Mary Ellen Pleasant: Difference between revisions

(PC and protected) |

m (Protected "Mary Ellen Pleasant": finished essay [edit=sysop:move=sysop]) |

(No difference)

| |

Revision as of 22:53, 28 December 2008

Historical Essay

by Chris Carlsson

File:Aframer1$mary-ellen-pleasant-young.jpg

Mary Ellen Pleasant young photograph

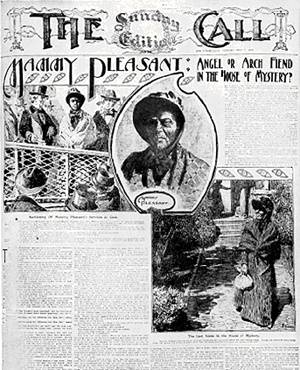

Sunday Call cover (Mary Pleasant)

Mary Ellen Pleasant (later in life)

Mary Ellen "Mammy" Pleasant became an important western terminus of the underground railroad in San Francisco during the 1850s. By placing maids and servants throughout the homes of San Francisco's rich, she came to wield (secret) power among San Francisco's elite.

When Mary Ellen was 10, her mother gave her the name of her white plantation-owning father, and also disclosed that Mary Ellen was descended from a succession of "Voodoo" Queens of Santo Domingo. A year later, Mary Ellen was sold to a man in New Orleans, Americus Price, and he decided to place her in a convent where she would be educated, and eventually freed. Later he sent her to live with friends in Cincinnati, since her educated intelligence would have eventually betrayed her in the antebellum South.

Mary Ellen's life took her in and out of various families and situations in New England and Virginia. She married James W. Smith, a Virginia plantation-owner and abolitionist. Throughout the late 1830s and early 1840s Mr. and Mrs. Smith smuggled hundreds of slaves to Canada as couriers along the Underground Railroad. When Smith died in 1844, Mary Ellen continued to outrage southern planters by helping scores of slaves to escape.

Things became too hot and Mary Ellen made her way first to New Orleans where Marie Laveau, the voodoo queen, deeply impressed Mary Ellen with her social power among all levels of New Orleans society. Mary Ellen stayed in New Orleans for a few months and learned about the practice of voodoo from Marie Laveau, though she didn't plan to copy Laveau's version exactly. By 1852, Louisiana planters were urgently searching for Mary Ellen Pleasant as the crafty intrigante who would stop at nothing in smuggling slaves through the Underground.

She sometimes visited plantations dressed as a jockey, other times as a shabby man on a delivery wagon. After getting trained as a cook, Mary Ellen found a job on a local plantation, right under the noses of the local gentry. Overhearing speculation about her origins one night, Mary Ellen made a hasty escape, and took the four-month sea journey around Cape Horn, arriving in San Francisco on April 7, 1852. On the journey she met a Scottish fellow named Thomas Bell, over whom she would maintain a powerful influence throughout the next three decades, as they both became millionaires speculating on mining and banking interests. By her death in 1904, Mammy had lost most of her fortune, and a good deal of Thomas Bell's as well.

Thomas Bell became a director of the all-powerful Bank of California and Mammy was his closest (and secret) advisor. Meanwhile, she bought and sold dozens of properties, running boarding houses and specializing in developing protéges (i.e. beautiful young women) whom she would endeavor to marry off to the nouveau riche miners and bankers that frequented her boarding houses. She also built a house, then far out of town, known as the "Geneva Cottage," at the corner of the San Jose road and Geneva (now the corner of Geneva and Bayshore Boulevard near the toxic wasteland of the Southern Pacific rail yards and the Brisbane lagoon), which was the infamous site of numerous wild bacchanalian parties, attended by wealthy San Franciscan men and a bevy of beautiful young women.

The mysterious death of one young woman at the Geneva Cottage led to a consolidation of Mammy's influence as she collected blackmail from the attendees to keep quiet the circumstances of her death. Other associates of Mammy also died mysteriously, often after trying to turn the blackmailing tables on Mammy, but she was never accused, tried, or convicted of any such crime.

She sought power through several primary techniques: she continued to sponsor runaway slaves as hundreds arrived in SF thanks to her aid. These people she placed in businesses and homes of the city, and they became her ears on the town. She sponsored and housed a number of young women, many of whom continued to follow her wishes for years. She spent a lot of her large fortune on the poor and destitute, earning considerable good will and power. She also used her position as madame to gain control through blackmail over many of the richest men in San Francisco, even helping them dispose of various children their dalliances gave rise to. And finally, Mary Ellen "Mammy" Pleasant used her talent with the voodoo religious rites to control her followers through religious terror.

Or so the received story has it. Recently researcher Susheel Bibbs has been digging through the record and has determined that a lot of what we know has been derived from articles in newspapers that were basically scandal sheets of the time. Helen Holdridge's book, from which I learned most of what I based this article on, suffers from the same problem. Bibbs' research adds some fascinating bits to the story.

"In 1858, amid a depression and widespread anti-black sentiment, she returned East to free a brother-in-law and to join John Brown's mission to free slaves near Harper's Ferry W. Virginia. Brown was hanged after being caught while trying to capture a federal arsenal; Pleasant escaped and returned to California. In 1863, after the Emancipation Proclamation and a similar law in California, Pleasant declared her race openly. She sued to win the right for blacks to ride the trolleys and won (Pleasant v. North Beach & Mission Railway) in 1868. Her businesses continued to grow, and her investment in quicksilver mining and silver/gold exchanges amassed a $30 million fortune for her and her silent partner, Scotsman Thomas Bell." [from "Mary Ellen Pleasant: Unsung Heroine" by Steve Crowe in Crisis, Jan-Feb 1999]

2007 postscript: Since this piece was originally written an excellent book, The Making of Mammy Pleasant by Lynn Hudson has been published. Hudson does a great job of analyzing the way the stories surrounding Mary Ellen Pleasant were manufactured from public records, courtroom testimonies, and gossip-sheet newspapers, recompiled by Helen Holdredge into her breathless accounts, and finally offers the most cogent view of who this woman was and how she managed to make her way at a time when neither women nor blacks had anything approaching full citizenship or rights. Hudson's book is definitely the best, first place to get the Pleasant story. Another recommended version is the fictional account by Michelle Cliff called Free Enterprise which dramatizes Pleasant's saga in historically detailed and insightful ways.