Smile and say "Freeze": Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

EvaKnowles (talk | contribs) added abstract |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

''By Marcy Darnovsky, originally published in'' It’s About Times, ''the Abalone Alliance newspaper, May-June 1982, p. 5.'' | ''By Marcy Darnovsky, originally published in'' It’s About Times, ''the Abalone Alliance newspaper, May-June 1982, p. 5.'' | ||

{| style="color: black; background-color: #F5DA81;" | |||

| colspan="2" |'''The Nuclear Weapons Freeze Campaign encouraged the creation of an agreement between the U.S. and the Soviet Union to stop the testing, production, and deployment of nuclear weapons and quickly garnered a mass movement in support of it. To political radicals like Darnovsky, while the campaign was successful for how it mobilized public opposition to nuclear weaponry, it was not radical enough; that is, the campaign did not adequately address the social and political systems that created and utilized nuclear weapons in the first place.''' | |||

|} | |||

If you can forgive me for dispensing with unnecessary politeness, I'll try not to carp and whine. I'll make my criticisms of the Freeze campaign frankly yet in a comradely manner. I'll maintain a spirit of cooperation and openness -- even though the Freezers refuse to take a stand against nuclear power, after we spent years trying to make the connection. Oops. This might be harder than I think. | If you can forgive me for dispensing with unnecessary politeness, I'll try not to carp and whine. I'll make my criticisms of the Freeze campaign frankly yet in a comradely manner. I'll maintain a spirit of cooperation and openness -- even though the Freezers refuse to take a stand against nuclear power, after we spent years trying to make the connection. Oops. This might be harder than I think. | ||

Latest revision as of 16:40, 7 July 2024

Historical Essay

By Marcy Darnovsky, originally published in It’s About Times, the Abalone Alliance newspaper, May-June 1982, p. 5.

| The Nuclear Weapons Freeze Campaign encouraged the creation of an agreement between the U.S. and the Soviet Union to stop the testing, production, and deployment of nuclear weapons and quickly garnered a mass movement in support of it. To political radicals like Darnovsky, while the campaign was successful for how it mobilized public opposition to nuclear weaponry, it was not radical enough; that is, the campaign did not adequately address the social and political systems that created and utilized nuclear weapons in the first place. |

If you can forgive me for dispensing with unnecessary politeness, I'll try not to carp and whine. I'll make my criticisms of the Freeze campaign frankly yet in a comradely manner. I'll maintain a spirit of cooperation and openness -- even though the Freezers refuse to take a stand against nuclear power, after we spent years trying to make the connection. Oops. This might be harder than I think.

Not that I'm completely against the Freeze. It deserves credit for having mobilized public opinion, put nuclear war in the headlines, and given Teddy Kennedy a platform from which to rejuvenate the Democratic Party.

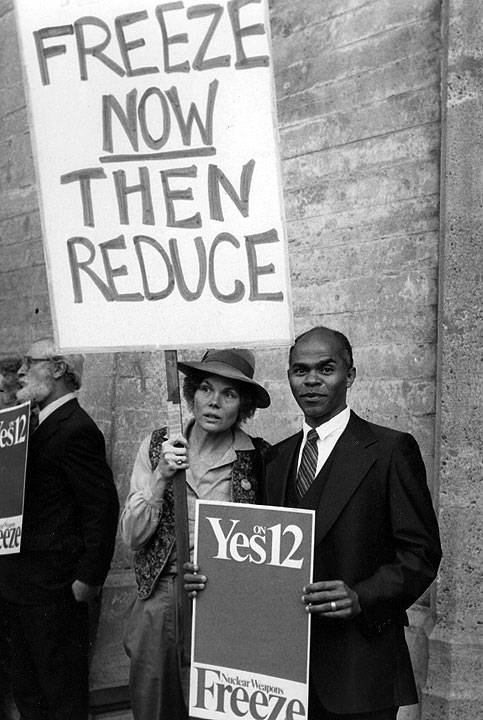

Nuclear freeze campaigners in San Francisco, 1982.

Photo:It's About Times

And I'm honored to be part of a movement that embraces ex-CIA directors, ex-members of the National Security Council, and retired rear admirals. Then there's that nice Republican couple I read about in The Chronicle, the ones with the $450,000 home in Orange County who were inspired to action when they realized that a nuclear war might not be so good for the property values. Is this what they mean by appealing to the lowest common denominator?

The Freeze really does have something for everybody. It gives liberals the moral capital (and, if the predicted flood of contributions materializes, the real stuff) that wins elections. It gives the bishops a chance to emulate the Polish church. For scientists who have spent their whole lives dreaming up monstrous new weapons systems, and retired admirals like Hyman Rickover who spent his whole life building the nuclear Navy, it provides a late-hour salve for troubled consciences and a last-minute claim to be Men of Peace.

Well, at least we know we're not alone. To paraphrase an ex-poet, when Hyman Rickover's scared, I'm scared.

If Teddy Kennedy gets his Freeze—the one he says will require a substantial buildup of conventional arms and armies—even the military will get what it wants. With the Falklands fresh in their minds, the Pentagon planners might well warm up to the Freeze. After all, it would give them wars they can actually fight.

Sure there are a lot of sincere and intelligent disarmers in the Freeze campaign, along with the cynical manipulators and professional bandwagon-jumpers. I don't go in for guilt by association. But I have noticed the phenomena of timidity by association, myopia by association, and liberalism by association. I've seen a lot of worry about respectability and little cultivation of rebelliousness.

There is a peculiar evangelistic flavor to disarmament respectability. Who would have thought all those hard-nosed, socially responsible professionals would find the faith at a pediatrician's revivals?

Not that the Freezers can be held responsible for Helen Caldicott's Joan-of-Arc complex. Caldicott's anti-political hysteria and her mother-cult tirades are a step beyond the general level of moral frenzy.

Yet the Freeze too is grounding its appeal in horror and fear. Tricky business. True, some people will be frightened into fighting back. Others will freeze (no pun intended) and wait for the danger to go away. And there are those who will come to like the titillation that accompanies the recitations of disaster. After all, one's own death is a drag but mass murder is fascinating. Nuclear apocalypse may not make it as a national pastime, but despair therapy could compete with est.

Sour grapes notwithstanding, I've got to say that the Freeze is very good at getting into the newspapers, Why, it took Three Mile Island for the antinuclear power movement to get a fraction of the attention. But that was a movement with distracting features like grassroots organization and silly ideas like participatory democracy. Well, at least the leaders of the Freeze don't try to push the rank and-file around. They seem satisfied if you sign the petition and go home 'til Election Day.

At the risk of seeming petty and picayune, what do we get if we get a Freeze? There's still that little matter of 25,000 American nuclear warheads—the ones that can destroy every Soviet city with a population over 100,000 forty times over. And from what I understand the Russians have a few megatons themselves.

Then there's those "conventional" weapons—napalm and other chemical unpleasantness, biological scourges, firestorms. Among this arsenal are the weapons that have actually been used since World War II, to the tune of 25 million deaths.

If we get a Freeze have we thawed the Cold War? Have we challenged the superpowers' ability to use their arsenals to absorb the rest of the world into their market nexus?

Yes, I know. You've got to start somewhere. The Freeze is a first step. Seems to me, though, that if you want people to stick around for the second step, you'd encourage some analysis and insight into the political and social institutions that are supported by the Bomb and that serve it so well.

There have been great upsurges of popular revulsion against nuclear war before this one. They too were apolitical, substituting fear and moral fervor for analysis. And they faded away like the hula hoop.

The most heartbreaking example is the large campaign against nuclear testing that persisted throughout the late fifties and early sixties. This movement focused on the health hazards of radioactive fallout, and in 1963 won a reprieve from atmospheric testing with the Partial Test Ban Treaty. A victory to be sure. But the treaty merely moved the testing underground, away from the narrow vision of the anti-testing forces.

The movement also failed to notice that the military's terms for agreeing to the treaty were stiff: promises of greatly increased levels of spending, research, and development. The Partial Test Ban Treaty turned out to be an excuse for new spirals in the arms race. The terms of this devil's bargain weren't clear until afterwards, but by then the movement was nowhere to be seen.

The Freeze's single-issue focus is less extreme. It is willing to consider the effects of nuclear weapons. But the Freeze campaign makes no attempt to deal with the causes or political underpinnings. It's still disarmament in a vacuum.

Now that I'm getting warmed up, just who's running this Freeze anyway? All I know is what I read in the newspapers—that the millionaire who funds it says he likes to call the shots. And that he doesn't like people with radical ideas, especially not in his movement. According to one of the pitches that came in the mail, "there is no way that even the most distorted mind can call these [Freeze supporters] 'crackpots' or radicals."

Well, I can take a hint as well as the next crackpot. But I do think the antiwar movement of the sixties and the antinuclear power movement of the seventies (along with Ronald Reagan) can take some credit for the current nuclear concern.

And I was hoping that the new upsurge would provide an opportunity for discussion about the social systems that create the nukes and use them to enforce wage slavery, hierarchical control, and geopolitical domination. I did wish that the moral fervor would create some room for intellectual passion and social imagination. That the debate would move beyond slogans as well as statistics. That the causes of war, as well as its consequences, would be considered.

I'm not asking for anything fancy. Just a little space in which to insert some slightly radical ideas. A little niche in the movement will do. Something a bit bigger than a bomb shelter.