The Golden Dragon Restaurant Massacre: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 61: | Line 61: | ||

At first, in the 1960s many of the gang kids were immigrants who brought gang behaviors learned on the streets of Hong Kong with them and found it difficult to fit in. By the late 1970s most of the gang kids were recruited from the schools among American-born Chinese, or immigrant children who had come to the U.S. too young to have had any Triad connections in the old country. After the Golden Dragon Massacre, with the Joe Boy leadership in jail, control of the Joe Boys devolved onto younger high-school-age members. There was some Joe Boy activity then, but it gradually withered away. | At first, in the 1960s many of the gang kids were immigrants who brought gang behaviors learned on the streets of Hong Kong with them and found it difficult to fit in. By the late 1970s most of the gang kids were recruited from the schools among American-born Chinese, or immigrant children who had come to the U.S. too young to have had any Triad connections in the old country. After the Golden Dragon Massacre, with the Joe Boy leadership in jail, control of the Joe Boys devolved onto younger high-school-age members. There was some Joe Boy activity then, but it gradually withered away. | ||

'' | ''—text and images excerpted with permission from Kevin Mullen's "Chinatown Squad" '' | ||

[[Image:Front-cover-web-resolution-72-dpi.jpg]] | [[Image:Front-cover-web-resolution-72-dpi.jpg]] | ||

Latest revision as of 13:22, 30 November 2021

Historical Essay

by Kevin J. Mullen

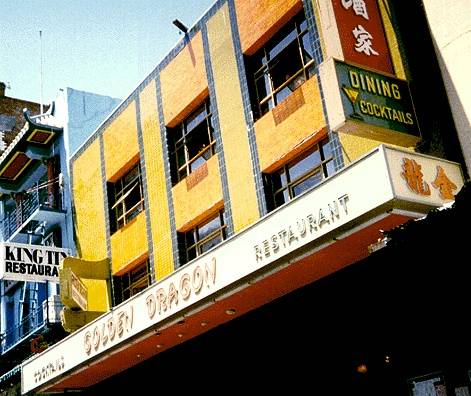

The Golden Dragon restaurant on Washington Street was the scene of an attack in 1977 that killed five and wounded eleven people.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Traditionally, the sale of illegal fireworks was a major source of gang revenue in Chinatown. As the Fourth of July approached each year, young people would stream into the district from all over the Bay Area to score firecrackers and other forbidden pyrotechnics. In 1977, the Ping Boys, residents of the Ping Yuen projects on Pacific Avenue, ran the operation under the auspices of the Wah Ching, for 10% of the take. On July 4, figuring to get their share of the accumulated loot, a group of Joe Boys headed for the Ping Yeun Projects with a view to robbing the Ping Boys of the proceeds from the sales. By this time, Joe Fong himself had been in prison for several years and though he was no longer on the street to exercise direct control of the gang, his followers continued to be referred to as “Joe Boys.”

Ping Yuen Housing Project, Chinatown.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The Joe Boys could not find a parking place nearby, and, as they approached the projects on foot, they were spotted by their enemies. In the ensuing gun battle on Pacific Avenue, one Joe Boy, Felix Louie, was killed and four others were wounded. The Joe Boys believed that Wah Ching leader Michael “Hot Dog” Louie had been the architect of their defeat. They retired to plan their revenge.

The Joe Boys nursed their wounded feelings for three months and then, in the early morning hours of Sunday, September 4, 1977, tipped off that Michael Louie was present in the Golden Dragon Restaurant on Washington Street, they attacked. (Although Louie was there, most of the gang was out of town in Northern California.) As three masked armed men entered the restaurant, Louie saw them coming and hit the floor. The shooters sprayed the restaurant with fire from shotguns and semi-automatic weapons, killing five innocent bystanders and wounding 11 more in the fusillade. The Golden Dragon Restaurant, significantly enough, was owned by the Hop Sing Tong whose youth faction, the Hop Sings Boys, were sometimes allied with the Wah Ching.

The press reaction was as might be expected. It was one thing for gangsters to kill one another in occasional street shootings; it was quite another thing to shoot down innocent bystanders in a public restaurant. The public was aroused, and called for action.

One week later, “Joe Boy” Yee Michael Lee was killed, and an associate was wounded in what was thought to be a reprisal attack by the Wah Ching at a Richmond District residence. It was then that the “Chinatown Squad” was re-established as a separate unit in the Police Department. This time, in deference to late Twentieth-Century-sensibilities, the unit was called “The Gang Task Force,” an appropriate omnibus term, as things turned out...

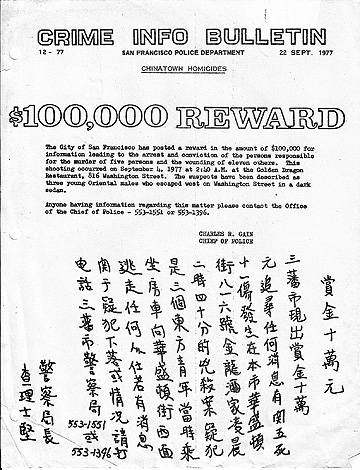

The first order of business was to solve the Golden Dragon Massacre, and the full resources of the unit were devoted to that purpose. Mayor George Moscone offered an unprecedented $100,000 reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the perpetrators.

Reward poster for leads on Golden Dragon Massacre

By late September, the Chinese Chamber of Commerce reported that Chinatown business had dropped off by 50 percent. The community and political pressure to make arrests mounted, as the days wore on. Radio journalist Russ Coughlin reminded everyone that just five years earlier the police had begun to get tough on the gangs with sweeps to prevent fights between warring factions, but had been forced off because of pressure from Chinatown after a few complaints that business was being harmed.

What followed in 1977 was what was probably the most complicated, sophisticated investigation in the annals of San Francisco crime. Over the next several months, investigators from the Gang Task Force, working with individual brilliance and masterfully orchestrated common efforts, pieced together the full story. Working in a bilingual, bicultural environment in a community famous for its reluctance to share information with outsiders, the officers identified and eventually brought to justice the perpetrators of the massacre.

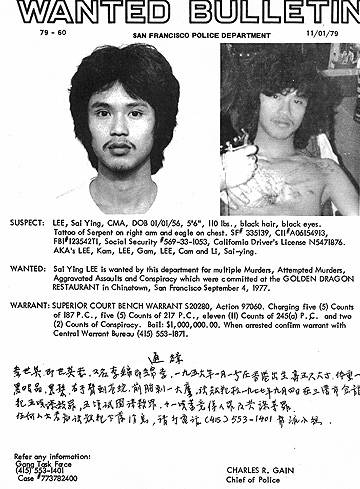

Wanted Bulletin for Sai Ying Lee, the sole remaining unarrested suspect in the Golden Dragon case. He has never been caught, but the arrest warrant charging him with being the getaway driver is still in effect. (Photo from SFPD.)

From the get-go, officers who had been working Chinatown crime realized that the Golden Dragon Massacre had been an attempted hit by the Joe Boys on the Wah Ching leadership. And, by the end of October, they had the names of the shooters. Admittedly, the information was obtained from a questionably erratic informant who was, himself, up to his ears in gang violence. To keep lines of information open, the police had to keep that information quiet.

There is a great difference between “knowing” something and obtaining enough information to make an arrest and, even more so, to gain a conviction. Amazingly, the investigators were able to keep the identity of the informer—and even the fact that there was an informer—out of the news. The slightest hint of the existence of an informer and the investigation would have been fatally compromised.

Over the next several months, Task Force investigators prowled Chinatown and other locations where the young gangsters hung out, creating the impression of a ubiquitous, all-seeing police presence. Predictably, Chinatown “youth advocates”—one of whom turned out to have been a close associate with the Joe Boys—again voiced their disapproval. In the aftermath of the massacre, however, their concerns did not gain much traction. (This particular “youth” advocate was later arrested himself in the course of the Golden Dragon investigation as one of a group selling explosives to an Alcohol Tax and Firearms agent.)

The legend of a taciturn Chinese “wall of silence” is—as is much myth and legend—rooted in reality. Jake Gittes, Jack Nicholson’s character in the 1974 movie Chinatown was right: “You can’t always tell what’s going on.” But there are limits to that characterization. “If you spend the time with them,” says retired Sergeant Dan Foley, who spent 24 years on the Chinese Gang Task Force, first as a member, and then from 1986 as its head, “and make the effort to get to know them, the Chinese will come to trust you, and take you into their confidence.” Beyond that, says Foley, the gangsters are more than willing to give information about opposing gangs, if you play them right.

By patiently developing relationships in Chinatown with these methods, the Gang Task Force was able to gather together the little pieces of the puzzle, which, when skillfully woven together, encased the perpetrators in an unbreakable evidentiary web. An indispensable feature of the investigation was the participation of officers familiar with Chinese culture, like Fred Lau and Heather Fong—and later in Gang Task Force investigations, Felix Thieu—who were able to translate documents and offer insights not normally understood by non-Asian investigators.

Inspector John McKenna and the Gang Task Force day watch in 1986. Standing l. to r. Leon Croure, Dick Gamble, Fred Mollat, Felix Thieu, Tim Simmons, and Dan Foley. A Noe Valley native, McKenna joined the Department in 1954 and was assigned to the Homicide Detail in 1969 when the Chinatown gang killings started in earnest. He was assigned Chinese homicide cases from the start and was a founding member of the Gang Task Force. From 1978 until his retirement in November 1986, he was the officer-in-charge of the Asian Section. (Photo courtesy of John McKenna)

In the end, the three shooters, the drivers on the night of the massacre, and assorted accessories prior to and after the crime, were arrested and convicted of assorted charges from first degree homicide on down.

Even as the investigation proceeded, gang violence in the schools in the Fall of 1977 continued. There were two further gang killings in 1977, that of Johnny Lee in late September, and Stephen Kong in November. But this time the Gang Task Force had the resources to stay on top of the situation. Perhaps one consequence of their efforts and the effect of the convictions was that, while gang conflicts persisted, the Chinese gang homicide rate declined. In all of 1978 there was only one gang killing in Chinatown, that of Louie Sing at 1018 Columbus in April. The Joe Boys continued their gang activities after the Golden Dragon arrests, but their numbers were sorely depleted and the mean age of the membership declined even further.

At first, in the 1960s many of the gang kids were immigrants who brought gang behaviors learned on the streets of Hong Kong with them and found it difficult to fit in. By the late 1970s most of the gang kids were recruited from the schools among American-born Chinese, or immigrant children who had come to the U.S. too young to have had any Triad connections in the old country. After the Golden Dragon Massacre, with the Joe Boy leadership in jail, control of the Joe Boys devolved onto younger high-school-age members. There was some Joe Boy activity then, but it gradually withered away.

—text and images excerpted with permission from Kevin Mullen's "Chinatown Squad"