Mission Life in Early 20th Century: Difference between revisions

(added notes) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 121: | Line 121: | ||

[[Fillmore Street 1910s|continue reading]] | [[Fillmore Street 1910s|continue reading]] | ||

[[category:Roads]] [[category:transit]] [[category:1910s]] [[category:Mission]] [[category:1920s]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:Schools]] [[category:Churches]] [[category:Baseball]] [[category:Jewish]] [[category:Irish]] [[category:German]] | [[category:Roads]] [[category:transit]] [[category:1910s]] [[category:Mission]] [[category:1920s]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:Schools]] [[category:Churches]] [[category:Baseball]] [[category:Jewish]] [[category:Irish]] [[category:German]] [[category:San Francisco 1865-1932: Politics, Power, and Urban Development]] | ||

Latest revision as of 15:14, 19 November 2021

Historical Essay

by William Issel and Robert Cherny

Streetcar tracks under construction at 24th and Bryant, looking south with Bernal Heights in distance, February 4, 1913.

Photo: SFMTA Photo U03873

North on Bartlett Street from 24th Street, January 1926.

Photo: Jesse Brown Cook collection, online archive of California I0050793A

Very different patterns of life and work characterized the Mission District, the large area along Mission Street, beginning at about Twelfth Street where Mission curves to run north and south, and extending west from Mission to the base of Twin Peaks and east to the industrial areas along the bay. While the Mission contained many neighborhoods, the area as a whole had a number of unifying characteristics during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The Mission was primarily an area of families. In 1900, more than 95 percent of the population in the few blocks along each side of Mission lived with family members or spouses, among the highest proportions in the entire city. Predominantly white, the population was about a quarter foreign-born and three-quarters or more of foreign parentage, with Irish and German the largest groups. The Mission was an area of single-family and two-family homes, its population density far below the citywide average and much lower than the densely packed South of Market. The street pattern of the area, however, was not much different from South of Market. The major thoroughfares that ran east and west through South of Market all curved at about Twelfth Street, to run north and south through the Mission District. By 1880, streetcars ran on these thoroughfares—Valencia, Mission, Howard (now South Van Ness), Folsom, Harrison, and, closer to the bay, Kentucky (now Third). Later, by 1902, there were also car lines on Bryant, Castro, and Guerrero, as well as a number of cross-town lines. Narrower residential streets ran between and parallel to these major thoroughfares, where one-, two-, or three-story wooden rowhouses housed one or two families. Businesses catering to the surrounding neighborhoods sprang up on the major thoroughfares, and large wooden churches were scattered at frequent intervals.(16)

Bartlett Street is a narrow residential street between Mission and Valencia. The 400 block on Bartlett, in 1900, had sixteen houses, which held seventeen households, divided almost equally between homeowners and renters. Of the forty-nine adults and twenty-eight children living on the block, only five of the adults were not family members—two of them were servants, three boarders. Six families consisted of two or three members, seven had four or five, and four had six or more. Thirteen of the sixteen families had both husband and wife present. Among the forty-nine adults, twelve had one or both parents born in Ireland, ten had one or both parents born in Scotland, seven had at least one English-born parent, five had parents born in Germany, and fifteen had both parents born in the United States.(17)

Nearly all the adult males on Bartlett Street had an occupation, but only three of the adult women worked for a paycheck. The largest number of the men held skilled blue-collar jobs, four in the metal trades, four in the building trades, one a printer, one a patternmaker. Two were supervisors, a foreman for the Southern Pacific Railway and a superintendent for the California Dry Dock Company. Only one, a boarder, worked as a day laborer, employed at a sheet-metal works. Eight held low-level white-collar jobs—four clerks, a collector, a customs inspector, a streetcar conductor, and a gateman for the Southern Pacific. Three were professionals—a lawyer, a physician, and a pharmacist. Two women were teachers, and the only other employed woman was a live-in servant for an elderly couple. Kinship and occupation were often closely related. All three men in the Jones family were ironworkers, one son as a machinist at Union Iron Works, the father and the other son as contractors, the only clearly identifiable entrepreneurs on the block. Two of the three Rutherford brothers also worked in the metal trades, one as a boilermaker, the other as a blacksmith. A carpenter’s son was also in the building trades, albeit as a plumber. The son of the dry dock superintendent worked in a shipyard, perhaps the same one as his father. The printer’s son was an apprentice printer. Two brothers were clerks.(18)

Bryant and 19th Streets, looking south, January 22, 1916.

Photo: SFMTA Photo U05053

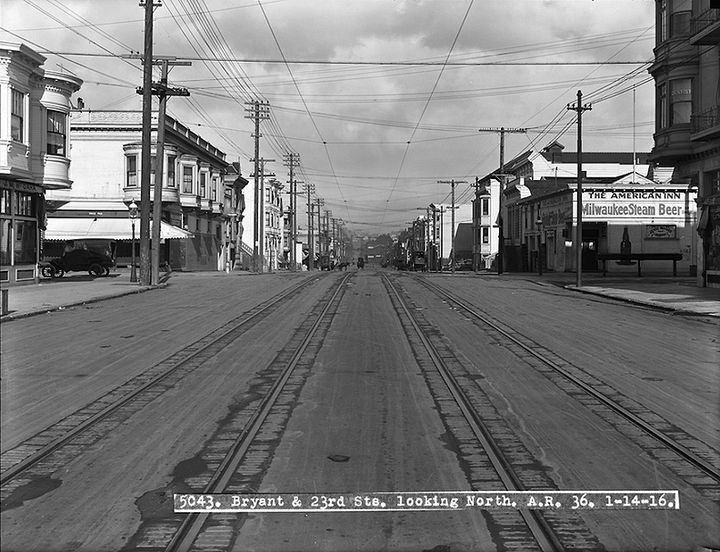

Bryant and 23rd Streets, looking north, Jan. 14, 1916, less than a year before the violent 1917 strike broke out.

Photo: SFMTA Photo U05043

The area around the 400 block on Bartlett held a wide variety of social institutions. Bethany Congregational Church was on that block, and three blocks up Bartlett was a Baptist church. An Episcopal mission church was located a few blocks to the west on Fair Oaks Street. Four German-speaking churches—Calvinist, Lutheran, Methodist, and Catholic—were all nearby. Methodist, Presbyterian, and Unitarian churches were not far distant. In addition to St. Anthony’s Catholic Church (German), there was also St. James, at Twenty-third and Guerrero. Haight Primary School was close by, on Mission between Twenty-fifth and Twenty-sixth. The block bounded by Bartlett and Valencia, Twenty-second and Twenty-third streets contained both Horace Mann Grammar School and Agassiz Intermediate Grammar School. There was also an evening school for adults at Horace Mann. St. Anthony’s maintained a parish school, and the Academy of the Immaculate Conception was near St. James. Mission High School, at Eighteenth and Dolores, was the only public high school in the district, but most residents of the area could reach it by a streetcar ride and a walk. Masonic Hall, on Mission between Twenty-second and Twenty-third, was the meeting site not just for the Mission Masonic Lodge and the Order of Eastern Star, but also for the Knights of Pythias, Native Sons of the Golden West, Order of Chosen Friends, Woodmen of the World, and two varieties of Foresters. Odd Fellows and Workmen met at Fraternal Hall, three blocks up Mission from Masonic Hall. Another Workmen’s lodge met on Twenty-fourth Street, two blocks east of Mission. The Mission Turn Verein (gymnastics club) had a hall on Eighteenth near Valencia where the San Francisco Männerchor (men’s chorus) and, most likely, other German groups met. In comparison with Tehama Street, the area around Bartlett Street had more churches, many more fraternal and social groups, and many fewer saloons. Only seven saloons and four restaurants were to be found in the area bounded by Mission and Valencia, Twenty-fourth and Army streets.(19)

North on Mission Street from 20th, showing corner of 19th and Mission, 1919.

Photo: Jesse Brown Cook collection, online archive of California I0050520A

The churches and lodges near Bartlett Street represent only a few of the social organizations and institutions to be found in the area. Every major Protestant denomination had put down roots in the Mission, usually in several locations—four Congregational churches, two Episcopal churches and two missions, three Evangelical churches (two German), three Lutheran churches (one Scandinavian, two German), six Methodist churches (one Swedish, one German), and five Presbyterian churches. In addition to St. Anthony’s and St. James, there were four other Catholic parish churches in the area. The largest ethnic groups were Irish and German, with the Irish numerically dominant. B’nai David was the only synagogue in the Mission District, and its congregation was small. A survey in the late 1930s found only 8 percent of the city’s Jewish population in the Mission.(20)

This example of an early synagogue in the Mission District is on 19th St. a block from Dolores Park. It is now a private residence.

Photo: Chris Carlsson, 1998

There was but one small city park in the Mission District until 1905 when a cemetery at Eighteenth and Dolores was converted into Dolores Park. However, many places of recreation and amusement served the area. Woodward’s Gardens, an elaborate private amusement park extending from Mission to Valencia and between Thirteenth and Fourteenth streets, opened in 1866; it featured live and stuffed animals, an amphitheater and art museum, botanical displays, and statuary. It remained a popular place for twenty-five years. The first San Francisco appearance of the Ringling Brothers’ Circus, in 1900, was in the Mission at Sixteenth and Folsom. Baseball was popular in the Mission District; the first organized game in the city was played in the Mission at Sixteenth and Harrison. A diamond was opened at Twenty-fifth and Folsom in 1868, and Recreation Park at Eighth and Harrison opened in 1897. Recreation Park, relocated to Fifteenth and Valencia in 1907, was home to the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League and, after 1926, to a second team, the San Francisco Missions. Both teams moved to Seals Stadium at Sixteenth and Bryant, also in the Mission, with the beginning of the 1931 baseball season. A race track opened in 1864 at Railroad Avenue between Twenty-fourth and Twenty-eighth streets (now Third Street, between Yosemite and Carroll).(21)

The Mission District as a whole had many characteristics not only of a family area but also of distinctly working-class or lower-middle-class families. An area with many religious or social institutions, it was home to many of the skilled workers employed in the manufacturing areas south of Market or along the bay, as well as home to some businessmen and professionals—those whose businesses were in the Mission, and others who had grown up there or who preferred the area for a variety of reasons. Some Mission District houses were clearly upper middle-class or even upper-class, home to successful merchants, ship captains, politicians, contractors, lawyers, or manufacturers. The dominant tone, however, was working-class. After the destruction of 1906 (which spared much of the Mission), the area became even more working-class and more Irish as families left South of Market and followed Mission Street south. For the next thirty years or so, until World War II, many Mission residents were consciously Irish, often consciously working class, and very conscious of being residents of “the Mish.”

Bryant at 22nd, looking north, March 14, 1916.

Photo: SFMTA Photo U05158

Bryant Street northerly near Alameda Street, April 1917.

Photo: SFMTA Photo U05732

Looking north on Bryant at 20th, March 13, 1918.

Photo: SFMTA Photo U06051

Bryant and 21st, looking in a southerly direction, July 19, 1919.

Photo: SFMTA Photo U06600

Bryant and 11th Streets, looking south, August 6, 1919.

Photo: SFMTA Photo U06627

View of powerhouse at Bryant and Alameda from the roof of Rainier Brewing Company, January 1920.

Photo: SFMTA Photo U06869

View north from top of Rainier Brewery, c. 1935, Bryant Street powerhouse at Alameda and Bryant at lower right.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp32.0110

Bryant near Division, looking south, 1941.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp67.0481

Notes

16. Table 104, “Population, Dwellings, and Families, for Places Having 2,500 Inhabitants or More: 1900,” Twelfth Census of the United States: 1900, vol. 2, pt. 2, p. 640; Table 23, “Population by Sex, General Nativity, and Color, for Places Having 2,500 Inhabitants or More: 1900,” ibid., p. 610; Table 5, “Composition and Characteristics of the Population for Wards (or Assembly Districts) of Cities of 50,000 or More,” Thirteenth Census of the United States: Abstract of the Census with Supplement for California, p. 616. The relevant assembly districts for 1900 are 32nd through the 36th, with the 34th and 35th squarely in the heart of the area; for 1910, the relevant districts are 31st through the 36th, with the 35th squarely in the center of the district. For a good, concise description of the built environment of the Mission District, see Randolph Delehanty, Walks and Tours in the Golden Gate City: San Francisco (New York, 1980), pp. 154, 161–167, esp. p. 167. For information on the history of many surviving houses from the late nineteenth century, see, in addition to Delehanty, Judith Lynch Waldhorn and Sally B. Woodbridge, Victoria's Legacy (San Francisco, 1978), pp. 41–89, which includes information on hundreds of specific houses as to the dale of construction, the contractor, and sometimes the early residents. See also Roger Olmsted and T. H. Watkins, Here Today: San Francisco's Architectural Heritage (San Francisco, 1968), pp. 102–111. For the streetcar lines, see “Guide Map of the City of San Francisco” (San Francisco, 1879); and Charles C. Hoag, ed., Our Society Blue Book: 1902 (San Francisco, 1902), pp. 37–44.

17. The 400 block on Bartlett still retains some sense of what it must have been like at the turn of the century, although the numbers today do not correspond to those in 1900. The houses at 476–478 and 494–496 are Italianate-style duplexes, dating from the 1870s. The house at 492 was probably originally a single-family, Italianate-style house. The building at 446, constructed in the Slick style popular in the 1880s, was probably once a single-family house, and the single-story Italianate collage at 432, built in 1875, is a splendid example of a working family’s home. Around the corner on Twenty-fifth Street between Bartlett and Mission are a row of four Stick-style two-story houses, probably from the 1880s. The information on families comes from 1900 Census Schedules, roll 103. See Nellie McGraw Hedgpeth, My Early Days in San Francisco (San Francisco, 1974), for an account of life on Twenty-first Street between Valencia and Guerrero, from about 1880 to 1889, esp. pp. 12–35.

18. The information on occupations comes from 1900 Census Schedules, roll 103, supplemented by reference to Crocker-Langley San Francisco Directory, 1900.

19. Crocker-Langley San Francisco Directory, 1900.

20. Ibid.; Ruth Kelson Rafael, Continuum—A Selective History of San Francisco Eastern European Jewish Life, 1880–1940, rev. ed. (Berkeley, 1977), p. 8; Zarchin, Glimpses of Jewish Life, p. 169; Fred Massarik, A Report on the Jewish Population of San Francisco, Marin County, and the Peninsula: 1959 (San Francisco, 1959), pp. 7–8, 11.

21. Delehanty, Walks and Tours, p. 162; Julia Cooley Altrocchi, Spectacular San Franciscans (New York, 1949), p. 154; Hansen, San Francisco Almanac, pp. 41, 232. For pictures of Woodward’s Gardens, see T. H. Watkins and Roger R. Olmsted, Mirror of the Dream: An Illustrated History of San Francisco (San Francisco, 1976), pp. 112–113. Jerry Flamm, Good Life in Hard Times: San Francisco's Twenties and Thirties (San Francisco, 1978), includes a lengthy account of the Seals, pp. 60–71.

Excerpted from San Francisco 1865-1932, Chapter 3 “Life and Work”