Geography of 19th Century San Francisco Business: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 86: | Line 86: | ||

[[19th Century Growth of Urban Transit Infrastructure |continue reading]] | [[19th Century Growth of Urban Transit Infrastructure |continue reading]] | ||

[[category:1870s]] [[category:1880s]] [[category:1890s]] [[category:Power and Money]] [[category:SOMA]] [[category:Downtown]] [[category:Irish]] [[category:food]] [[category:Corporations]] | [[category:1870s]] [[category:1880s]] [[category:1890s]] [[category:Power and Money]] [[category:SOMA]] [[category:Downtown]] [[category:Irish]] [[category:food]] [[category:Corporations]] [[category:San Francisco 1865-1932: Politics, Power, and Urban Development]] | ||

Latest revision as of 15:03, 19 November 2021

Historical Essay

by William Issel and Robert Cherny

Ferry Building 1889, foot of Market Street

Photo: Private Collection, San Francisco, CA

The clamor of the commercial city was nowhere as marked as at the point where waterfront activity joined with the busy traffic of merchandising and wholesaling at the lower end of Market Street. Market Street's unusual 120-foot width made it a dramatic swath that separated most of the financial and commercial city on the north from the more industrial sectors to the south.

Except for the handful of industrial firms of the scale of Spreckels's refinery, San Francisco's economic life in the 1880s was centered primarily in the area bounded on the west by Larkin Street, on the southwest by Seventh Street, and on the north and east by the waterfront. The bustle of trade on the city streets reflected the city’s major activities.

A traveler alighting from one of the ferries at the foot of Market Street in the 1880s would have found surroundings familiar to residents of other port cities, whether Boston. New York, Philadelphia, or Baltimore. For example, the firm of Coffin and Hendy, already two decades old in the mid-eighties, stood close by the water, selling ship chandlery and naval stores. Next door another twenty-year-old business, the shipping agents Goodall, Perkins, and Company, directed the Pacific Coast Steamship Company (which they had originally organized and later sold to eastern capitalists of the Villard syndicate). Goodall, Perkins, and Company launched the first steamers engaged in the whaling trade, and they owned large holdings of stock in the Oceanic Steamship Company and the Arctic Oil Works. The company also served as the agents of the Pacific Coast Railway Company and the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company. Between them, these railroads and the shipping lines handled much of the coastal trade between San Diego and Alaska except for coal and lumber.(9)

A bit further down Market Street, the four-story, red-brick building of Hawley Brothers Hardware Company announced its products (and suggested the importance of agriculture in California) with huge painted signs: “Schuttler Farm and Spring Wagons, Portable Engines, Threshers, Buckeye Mowers and Reapers, Headers, Gang Plows, Cultivators, Rices’ Straw Burning Engines.” The wagons, steam tractors, and harvesting machines parked on the pavement outside made the firm’s business clear to everyone who passed by. Thirty years in business, this corporation handled a payroll of $5,000 a month, declared annual sales from imports and manufactures of close to $2 million, and tapped the entire region west of the Rockies, Mexico, South and Central America, and Hawaii.(10)

In 1852, two years before Charles A. Hawley opened his hardware store in San Francisco, Collis P. Huntington and Mark Hopkins set up a similar business in Sacramento. In 1870, after they and Leland Stanford and Charles Crocker, the other members of the “Big Four,” completed the Central Pacific’s transcontinental railroad, Huntington and Hopkins opened a branch of their hardware business in San Francisco. During the 1880s, the firm’s four-story building provided an imposing reminder of the wealth of its owners. In addition to hardware, the firm handled all sorts of iron and steel products; traded throughout the Pacific states, the territories, and Mexico; operated a branch on Broad Street in New York; and stood on such a firm foundation of capital that, in the words of one contemporary, “its credit in commercial circles is equivalent to cash.”(11)

Manufacturers occupied the upper floors of four-story buildings further west on Market Street, lending this part of downtown San Francisco something of a New York flavor. Kraker and Israel established their workshop for the making of women’s and children’s clothing in the face of “almost overwhelming opposition” from eastern competitors in 1865, but in twenty years they had managed to displace imports to the point that one sympathizer claimed that “the entire Pacific Coast” was “under tribute” to them. S. and G. Gump (founded in San Francisco in 1860) employed fifty workers in the production of mirrors, mouldings, frames, hardwood mantles, and bric-a-brac furniture. A few blocks away on Stevenson Street, a similarly large building housed both the woolen import business of Stein, Simon, and Company and the wine vaults of J. Gundlach and Company, owners of the “Rhinefarin” vineyards near Sonoma and suppliers of California wines to the East.(12)

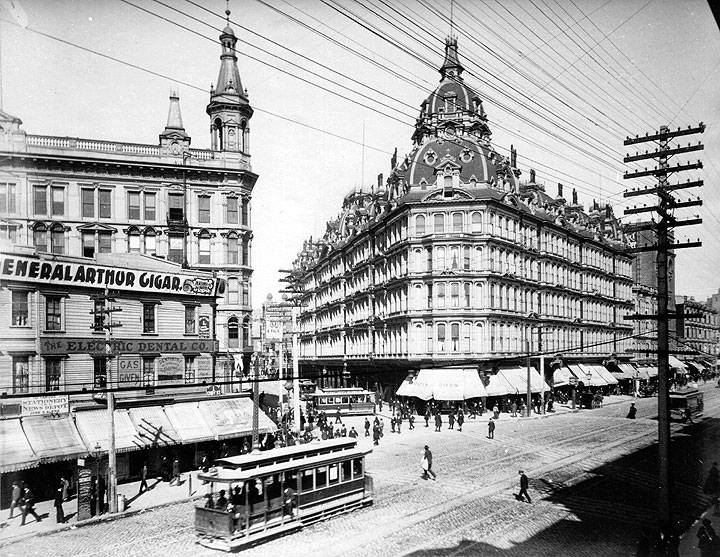

Baldwin Hotel at Market and Powell from the 1870s to the 1906 earthquake, seen here in the 1880s.

Photo: Private Collection

Some of the wine from the Gundlach cellars may have found its way to the dining rooms of the Grand Hotel or the Palace Hotel, establishments facing each other across New Montgomery at its junction with Market. Like the Baldwin Hotel further up Market at the corner of Powell, the Palace Hotel opened in the 1870s, offering guests their choice of 755 rooms. With its seven-story, red-brick facade visible for miles in most directions, the hotel had “myriads of bay windows,” which served to “partly relieve the imposing exterior from the appearance of oppressive massiveness by which it would otherwise be characterized.”(13)

The Hibernia Savings and Loan Society, the city’s leading savings bank in 1880 with over $15 million in resources, stood only a few steps away. The bank’s president and board of directors still consisted of the wealthy group of prominent Irish-Americans who had organized the bank in 1859. Myles D. Sweeney served as president, Robert J. Tobin acted as secretary, and real estate developer John Sullivan, as well as iron manufacturer and railroad entrepreneur Peter Donahue and French merchant Gustave Touchard, served on the board. By the 1880s, the Hibernia had already played an important part in the business and residential development of the city by financing both the acquisition and subdivision of property and the construction of downtown commercial structures and outlying family dwellings. San Francisco’s large Irish population made up the largest single group of depositors and borrowers, but the bank did not deal with Hibernians exclusively. The immigrant French banker Francois L. A. Pioche financed his subdivisions in San Francisco’s Mission, Potrero, and Visitacion Valley districts with loans from the Hibernia, and the bank subsequently made hundreds of loans for the construction of modest wooden rowhouses in these predominantly working-class neighborhoods. William Chapman Ralston built his Palace Hotel (on a site originally owned by Hibernia's first president John Sullivan) with Hibernia loans that totaled $1 million.(14)

The Nevada Bank, the city’s leading bank in 1880 (capitalized at $10 million with over $20 million in resources), rested upon wealth from the Comstock that had been brought to San Francisco by its “Silver King” founders. Established in 1875 by James C. Flood and William S. O'Brien in the chaotic last days of William Ralston’s tenure as president of the Bank of California, the Nevada Bank’s solvency contributed to the city’s financial stability in the latter part of the depression-wracked decade of the 1870s. John W. Mackay and James G. Fair, the other two “Silver Kings,’’ also served as directors. The Nevada Bank, at Montgomery and Pine streets, was only a short walk from the California and Sansome Street location of the Bank of California.(15)

Like the Nevada Bank, the Bank of California brought profits from Nevada silver to San Francisco where it was transformed into capital for the development of commerce, industry, and the built environment. Before he died in 1875 at the age of forty-nine (probably from a stroke while swimming on the day he was forced out as the bank’s president), Ralston used the banks resources to initiate a dizzying array of developments in San Francisco and the Bay Area. “He wanted,” wrote friend and associate Asbury Harpending forty years later,

to see his State and city great, prosperous, progressive, conspicuous throughout the world for enterprise and big things. I think it was this imagination, this ambition, that kept hurrying him into one big undertaking after another, many of which were way ahead of time.

Ralston’s San Francisco projects included a southern extension of Montgomery Street, the Mission Woolen Mills, the Cornell Watch Factory, the Kimball Carriage Factory, the West Coast Furniture Factory, a sugar refinery, a dry dock at Hunter’s Point, and the Palace and the Grand hotels.(16) William Alvord headed the Bank of California in the eighties. An importer and wholesaler, Alvord had been one of the founders of the Risdon Iron Works and a former city mayor. Bank of California resources ($10 million), though only half those of the Nevada Bank in 1880, still stood at over twice those of its closest rival. Ten of the city’s eighteen largest banks stood nearby on California Street, and all but two—the California Savings and Loan Society on Powell Street and the Savings and Loan Society at 619 Clay Street—were within a two-block radius of the Bank of California.(17)

Several blocks to the north, finance gave way to commerce. Some manufacturing could also be found here in the eighties. Eugene Thomas, for example, at 617 Sansome Street, operated an importing firm specializing in French wines, liquors, truffles, Vichy water, and other continental delicacies. Drake and Emerson, established in 1863, carried out their commission business in fruits and vegetables on Sansome between Washington and Merchant streets.(18)

J. W. Schaeffer and Company, a pioneer in cigar making on the West Coast and president of the Cigar Manufacturers Association, produced Green Seal, Bon Ton, Chromo, and Correro cigars at 231 and 323 Sacramento Street. H. Plagemann and Company, founded in 1862, produced the Las Operitas and Sublime brands nearby. Smokers who preferred cigars and tobacco from New York, Virginia, or Havana could visit Esberg, Bachman, and Company at the northeast corner of California and Battery streets. At Clay and Sansome streets, also close by Chinatown, Porter, Slessinger, and Company operated their boot and shoe factory and marketed their “Iron Clad’’ products throughout the region.(19)

Lower California Street housed the offices of one of the state’s leading flour mills, Sperry and Company. The firm kept its city office at 22 California Street while the mills in Stockton ground out the thousand barrels a day that were then shipped via the San Joaquin River to San Francisco and then all over California as well as to China. Battery, Front, and Davis streets were crowded with other commission merchants and importers, whose warehouses covered large plots of land, as well as small manufacturers. Moody and Farish, for example, oldest wool commission merchants on the West Coast, represented the region’s largest wool growers and had recently expanded into handling the lucrative trade in hops. Baker and Hamilton, at the intersection of Market, Davis, and Pine streets, occupied the entire lower part of a block, and its warehouse held agricultural implements and hardware that the firm sold throughout the Pacific region.(20)

Baker and Hamilton had begun near Sacramento in 1849. Levi Strauss opened in San Francisco in 1853. By the mid-1880s, Strauss’s dry goods business occupied a four-story building and employed “a small army” of workers who maintained the company’s connections with both large and small settlements throughout the West. Kahn Brothers and Company, located at 25 and 27 Battery, imported silks, velvets, cashmeres, and other fancy goods from Germany, France, and England. San Francisco retailers depended on Kahn Brothers for products direct from Belfast, Glasgow, St. Etienne, Roubaix, Lyons, and Paris.(21)

Smoke from factory chimneys and sounds from foundries filled the air in the streets leading away from Market Street on the south, distinguishing that district from the north side of Market. David Kerr manufactured carriages, wagons, and heavy trucks at his factory on Beale Street. Tatum and Bowen produced heavy sawmill machinery nearby.

The National Iron Works, at Main and Howard streets, employed one hundred men building stationary engines, ore crushers, and flour and sawmill equipment. Established in 1879, the firm had up-to-date equipment, which allowed it to compete successfully with more established companies One of these, Aetna Iron Works at 217 Fremont Street, established in 1866 originally specialized in mining machinery but later diversified its products’ W. F. Buswell, located at 108 Main Street, manufactured quartz and flour mills, elevators, and sidewalk hoists and had prospered since the founding of the company in 1858. Liebes Brothers and Company, on Fremont Street employed five hundred workers in a factory situated on the upper floors of their building, and they sold their brands profitably in New York, New England, and the southern United States despite competition from the locals.(22)

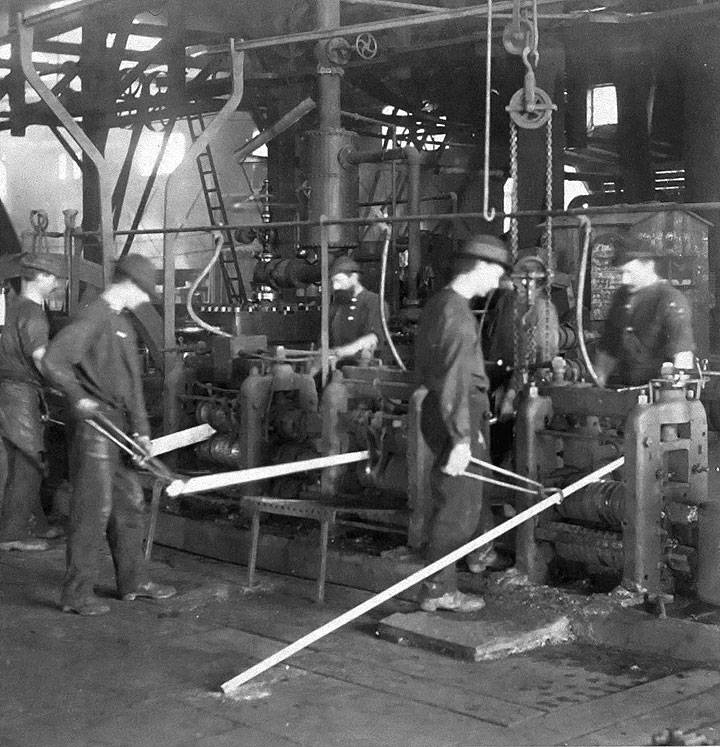

Pacific Rolling Mills. This first great ironworks on the south waterfront rolled its first bar of iron in July 1868. At the time Muybridge took this stereo view in 1869, the mills produced bar iron and had a capacity of 3,000 tons a year. Later they erected puddling furnaces and produced pig iron. From these mills came iron for the railroad; wrought-iron shafts for steamships and mills; I-beams for bridges, girders and housebuilding; rod, bar, and angle iron, chains, bolts and nuts; entire iron bridges; and the iron rails for streetcars and cable cars in San Francisco. By 1880 the mill ran day and night, producing 30,000 tons a year and employing 450 men at wages higher than on the East Coast. Irish immigrants headed for the big mills the moment they arrived in town; skilled iron moulders from Scotland made up a large part of the work crew.

Photo: Bancroft Library (I0046722)

In the Potrero District close to the southeastern shore of the city, the Union Iron Works and the Pacific Rolling Mills joined Spreckels's California Sugar Refinery to create a heavy industry sector. The Union Iron Works, begun in 1849 as a modest concern by Glasgow-born (of Irish parents) Peter Donahue, was headed by George W. Prescott in the late 1880s, with Irving M. Scott as general manager. Over 1,200 workers operated the mammoth plant that spread across fifteen acres and included a complete shipyard, a rolling mill, foundries, pattern shops, machine shops, and one of the largest hydraulic lift docks in the United States. The firm produced mining machinery, heavy agricultural implements, ships, and even locomotives. William Alvord headed the Pacific Rolling Mills, located nearby at Potrero Point, where eight hundred workers operated six trains of rollers, twenty- five furnaces, fifty-four boilers, fifteen engines, and eight steam hammers. The Pacific Rolling Mills turned out 30,000 tons of iron and 10,000 tons of steel annually. It had rolled the first steel rails made on the Pacific Coast (for the Mission Street Railroad) and supplied the tracks for the Market Street cable railroad system. Its engines also powered sea-going craft and ran machinery in the Comstock.(23)

Notes

9. Fred H. Hackett, ed., The Industries of San Francisco (San Francisco, 1884), pp. 141, 79, 91.

10. Ibid., pp. 67, 133.

11. Ibid., p. 53.

12. Ibid., pp. 92, 118, 85, 83, 84, 181.

13. Langley's San Francisco Directory, 1880–1881 (San Francisco, 1881), pp. 18–19; Hackett, ed.. Industries of San Francisco, p. 67.

14. Charles A. Fracchia, “The Founding of the Hibernia Savings and Loan Society,” unpublished typescript in the authors’ possession, pp. 6, 9-11; Armstrong and Denny, Financial California, p. 190; Langley’s San Francisco Directory, 1879–1880 (San Francisco, 1880), p. 23.

15. Ira B. Cross, Financing an Empire: History of Banking in California, 4 vols. (Chicago, 1927),1:370, 402–404.

16. David Lavender, Nothing Seemed Impossible: William Chapman Ralston and Early San Francisco (Palo Alto, 1975), p. 382; Asbury Harpending, The Great Diamond Hoax and Other Stirring Incidents in the Life of Asbury Harpending (San Francisco, 1913), p. 125; Neil C. Wilson, 400 California Street: A Century Plus Five, 2nd ed. (San Francisco, 1969), p. 49.

17. Armstrong and Denny, Financial California, p. 191; Langley’s San Francisco Directory, 1879-1880, p. 23.

18. Hackett, ed., Industries of San Francisco, pp. 161, 174.

19. Ibid., pp. 1 17, 157, 155, 133, 168, 64.

20. Ibid., pp. 167, 74, 96, 84; see also David Warren Ryder, A Century of Hardware and Steel (San Francisco, 1949), pp. 63–69.

21. Hackett, ed., Industries of San Francisco, pp. 151, 83.

22. Ibid., pp. 154, 138, 144.

23. Ibid., pp. 188, 173, 125, 106–107, 54, 57.

Excerpted from San Francisco 1865-1932, Chapter 2 “Business and Economic Development”