Prefabs in the Gold Rush: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

m (Protected "Prefabs in the Gold Rush" ([Edit=Allow only administrators] (indefinite) [Move=Allow only administrators] (indefinite))) |

(No difference)

| |

Revision as of 10:02, 12 July 2021

Historical Essay

by Paul Fisher

Today when most people think of prefab housing, they think of Airstreams or "doublewides" or edgy buildings from avant-garde magazines. In the early 20th century they were an ideal of future civilization for modernists like the Bauhaus. But they were fully operational in the mid-19th century, with a definite presence in the raw, rough new city of San Francisco. Thousands rushed in but there was almost no infrastructure or housing stock for them. Tents and shanties were popular by default. Some slept on wagon beds or under overturned boats. There were no local construction trades or suppliers of building materials. To fill this void, entrepreneurs resorted to "packaged" houses mostly from from the Eastern US.

New York was a major source. It was estimated that 5000 houses had been sent from NY to SF, or were under contract, by fall of 1849. Boston, Maine, and Philadelphia were suppliers too. There was a wooden cottage from Hamburg, Germany, in 42 packages. From Le Havre, France, came a "maison demontee" valued at 800 francs. China was another source. A two-room house from China sheltered Jessie Benton Fremont (wife of John C. Fremont) in Happy Valley, summer of 1849. The house was made of sliding panels, like furniture and without nails, and often a Chinese carpenter or two was included in the package, to assemble it. Iron structures were sent west too. Their attraction was that they were strong and non-combustible, very appealing to a town that had already caught fire several times in such a short period. But they could have a large solar heat gain, so were favored for commercial rather than for residential use, and in a wildfire the iron would melt. All these buildings had to be shipped around Cape Horn, and so transportation was a major cost factor. Toward the end of the prefab boom, mid-1850s, when supply was catching up with demand, the fabricators sometimes barely broke even, or took a loss. Some shippers, rather than send the houses back to the East Coast, would send them on to Hawaii and sell at a discount. Three photographs show examples of prefabs.

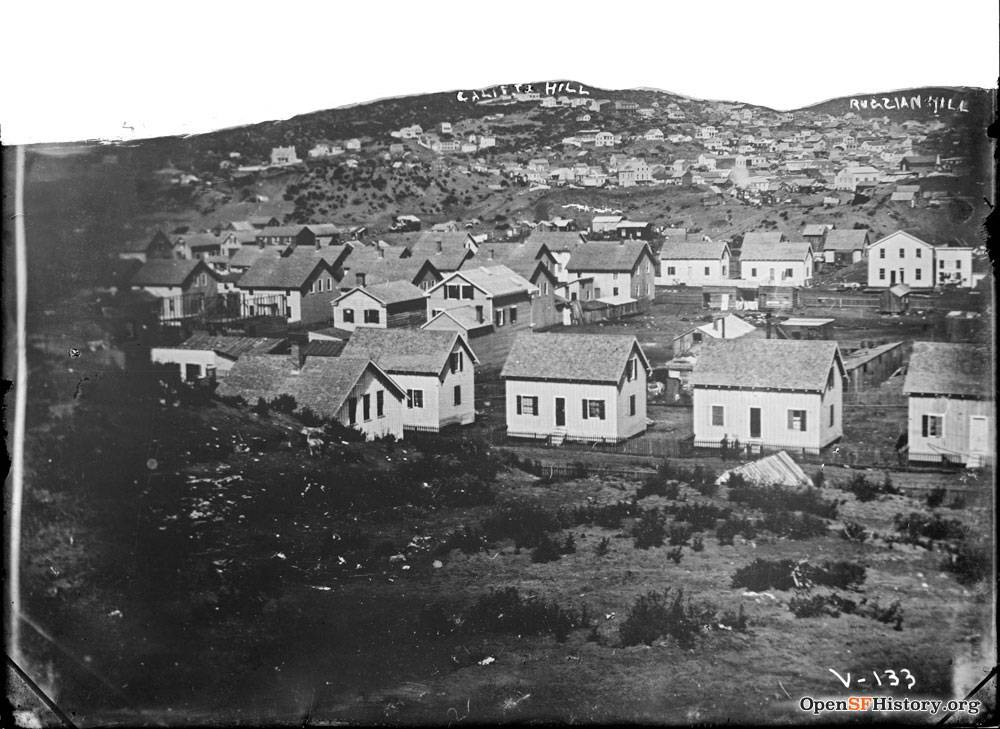

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org

The first photograph is one of the earliest views of San Francisco, part of a panorama looking north from Rincon Hill, which in those days really was a hill. In the foreground is Happy Valley, formerly a tent city, located around 3rd and Howard. Identical prefab residences are conspicuously scattered all over, like little Monopoly houses.

Photo: Photo, Library of Congress, HABS CAL, 48-BENI, 12

A second photograph shows a charming prefab Carpenter Gothic cottage from late 1849. It actually exists in Benicia, known as the Frisbie-Walsh house, but it had two other clones, one in San Francisco, known as the Burritt house (no longer extant). The other clone still exists however, in Sonoma, known as Lachrymae Montis, residence of General Mariano G. Vallejo. John Frisbie was Vallejo's son-in-law. Burritt is the famous "Maltese Falcon" alley on Nob Hill. The City of Benicia was named after the wife of M. G. Vallejo, just as the City of Vallejo was named after Vallejo himself. Lot of history here!

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

The third photograph is the prefab Stanyan house, 2006 Bush Street, one of the 3 or 4 oldest existing houses in SF, from 1854. It is City Landmark No. 66, occupied by the family for over 110 years. It came from Boston and is very simple and modest, like most pre-Victorian structures.