The Pre-European Landscape: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

[[San Francisco 1816 | Prev. Document]] [[Yerba Buena-Good Herb | Next Document]] | [[San Francisco 1816 | Prev. Document]] [[Yerba Buena-Good Herb | Next Document]] | ||

[[category:Ecology]] [[category:1776-1823]] [[category:1823-1846]] [[category:Indigenous]] [[category:Presidio]] | [[category:Ecology]] [[category:1776-1823]] [[category:1823-1846]] [[category:Indigenous]] [[category:Presidio]] [[category:Reclaiming San Francisco]] | ||

Latest revision as of 21:07, 21 November 2021

Historical Essay

by Pete Holloran

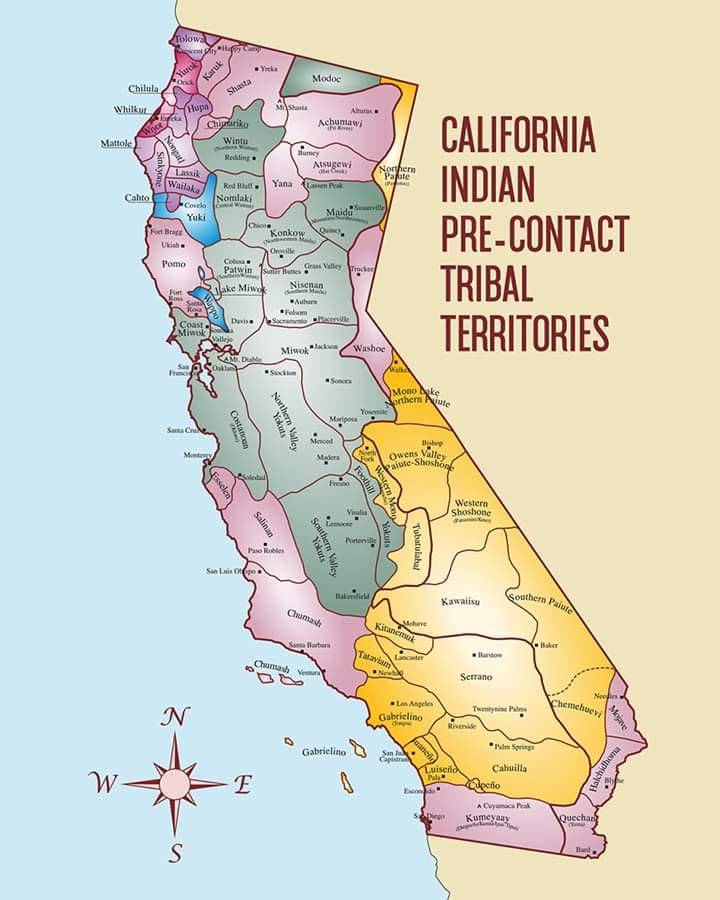

Pre-Contact map of California Indigenous territories.

Map courtesy H.O.M.E.Y., via Facebook

On a spring day in 1776 one of the first Europeans to see this land marveled at the plentiful wildflowers near his campsite. "There are yerba buena and so many lilies," Father Pedro Font wrote, "that I had them almost inside my tent." Firewood was abundant, but Font was compelled to note "the lack of timber." Coast live oaks, willows, and other hardy species flourished where San Francisco's unusual environmental conditions made the land uninhabitable for tall trees.

Thickets of scrubby trees supplied essential resources for the indigenous inhabitants of the San Francisco peninsula, the Ramaytush tribe of the Ohlone Indians. Coast live oaks--prized for their acorns--may have been the most important, but more than 150 other plants were also used by the Ohlone for food, medicine, cosmetics, and even insecticides. Presidio tidal marshes--now completely filled in--once provided the Ohlone with at least 29 species of fish, numerous birds and mammals, even the occasional whale and grizzly bear.

The natural world provided the Ohlone with variety, but not in such abundance without thoughtful management on their part. Willows, for example, needed pruning to encourage the straight young poles preferred by basketweavers. Fire was perhaps the most potent tool, as it prevented shrub encroachment on grasslands rich in edible bulbs and kept the landscape open for deer and other animals of woodland margins. One visitor recorded such fires while camping near Mission Dolores in late October 1816: "All night," he wrote, "great fires burned on the land at the back of the harbor; the natives are in the habit of burning the grass, to further its growth."

So when Father Pedro Font walked north from his camp at Mountain Lake and encountered a "very open" mesa, he was probably witnessing an inhabited landscape, managed by the Ohlone to meet their need for diverse natural products. Without burning, the rugged and windswept mesa may have been a thicket of manzanita and poison oak, but instead it offered "an abundance of wild violets" and fine pasture grasses, perpetuated by late autumn fires.

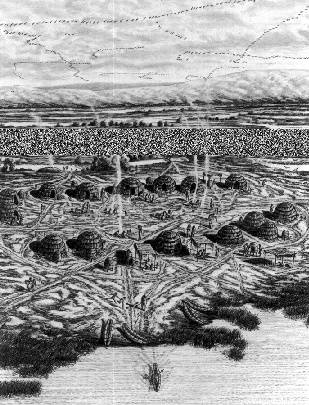

A typical Ohlone bayside village as pictured in The Ohlone Way.

Image: Heyday Books, Berkeley, CA

After ascending a hill north of Mountain Lake (probably the present-day Rob Hill), Father Pedro Font was captivated by "a most delightful view" of the Golden Gate, the Farallones, and San Francisco Bay. "There would not be anything more beautiful in all the world," he declared, than a city built here. This panoramic view is now blocked by non-native trees planted by the Army.

[adapted from Pete Holloran, "Seeing the Trees Through the Forest: Oaks and History in the Presidio," in Reclaiming San Francisco (San Francisco: City Lights, 1998)]