Rise and Fall of FM Rock: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 86: | Line 86: | ||

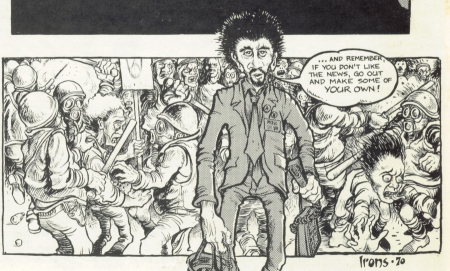

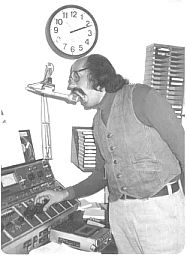

[[Image:Scoopmakenews.JPG]] | [[Image:Scoopmakenews.JPG]] | ||

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/ScoopsLastNewsShowSideB" width=" | <iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/ScoopsLastNewsShowSideB" width="500" height="30" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe> | ||

'''Side B of an album-version of Scoop's Last News Show''' | '''Side B of an album-version of Scoop's Last News Show''' | ||

Revision as of 13:31, 21 May 2018

Historical Essay

By Steve Chapple, Robert Garofalo, and Joel Rogers

May 1976, originally published in Mother Jones magazine

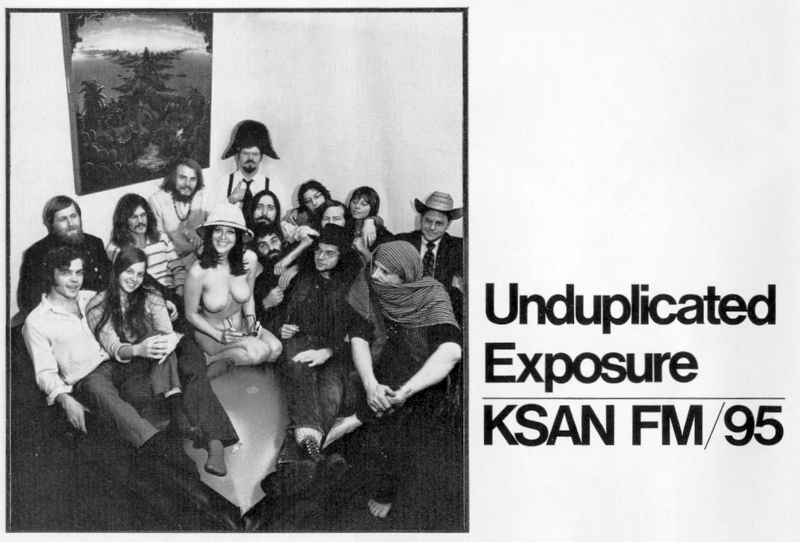

KSAN-FM print ad, December 1971

It was November 1967, when San Francisco DJ Big Daddy Tom Donahue, the founder of FM rock, delivered the epitaph to AM Top 40 radio, the jangle-jingle medium that until then had monopolized the airways, bringing you All the Hits, All the Time. "Top 40 radio, as we know it today and have known it for the last ten years," intoned Donahue, "is dead, and its rotting corpse is stinking up the airways." Now, less than a decade later, Donahue's own creation, "free form revolutionary radio," has been laid to rest, as well.

Since World War II several waves of creative radio have emerged and been co-opted in the United States. In the mid '50s, thumping, ranting independent rock 'n' roll DJs like Alan Freed replaced the polished announcers working at established network stations. Freed's rock 'n' roll radio brought popular singers like Chuck Berry and Elvis Presley to a youth audience that had been stifled by the old-fashioned crooning of singers like Perry Como and Patti Page. In the early '60s, as rip-roaring rock softened to Philadelphia schlock, rock 'n' roll radio tightened its format considerably to include only "the hits" in a rigidly structured rotation known as Top 40. When folk rock, psychedelic music and complicated British rock emerged in the mid '60s, Top 40 AM stations refused to play it. This new music found its medium on FM radio. But in a replay of the '50s, FM rock, too, is being co-opted. Competition from FM stations that play Top 40 singles, or a highly commercial mixture of singles and album cuts, is squeezing the creativity from progressive FM rockers. Other factors besides competition are at play: corporate ownership, censorship, and the out-of-hand financial success of the medium.

THE FLOWERING OF FM

FM rock radio of the '60s was a child of fortunate coincidence: a meeting of new music with the revitalization of an old medium-frequency modulation. In 1965 the Federal Communications Commission ruled that broadcasters owning FM as well as AM stations in cities with populations of more than 100,000 could not duplicate their AM programming on FM more than 50 per cent of the time.

Since programming an FM station half of the broadcasting day costs nearly as much as changing the broadcasts for the entire day, most owners moved to split off their FMs entirely. Dozens of FM stations were subsequently opened to innovative programming directed at new audiences.

At almost the same time, especially on the West Coast, the new folk rock of Bob Dylan and the Byrds, and the psychedelic music of the Grateful Dead, the Jefferson Airplane and others was knifing through the bubblegum sounds of the time. Trying to appeal to the lowest common denominator in its audience, AM radio continued to play schlock.

Although 38, Tom Donahue was no stranger to the 1967 rock scene. He had produced the first Beatles concerts in San Francisco and formed Autumn Records, an artistically strong San Francisco label that had first recorded the Beau Brummels and Grace Slick and the Great Society. After Autumn Records folded, Donahue lay low for a year in San Francisco's North Beach and formulated an idea for a new type of radio. He was able to develop his new radio concept for only eight years, until his death in April 1975, at the age of 46.

The radio format Donahue conceived would play stereo rock with a minimum of commercials and be introduced by low-key disc jockeys, speaking in a normal tone of voice. The DJs were to act as Fabian Annette Frankie if they were at home entertaining friends. It was to be the opposite of strident Top 40 formula radio. Donahue took the concept to KMPX-FM in San Francisco and began to broadcast the 8 p.m. to midnight show. The program was an immediate success, and Donahue soon extended the format to the rest of the station's broadcasts; within a short time he flew to Los Angeles to establish the second FM rocker at KPPC.

In New York, executives at Metromedia (a sophisticated radio and television conglomerate originally based in the food brokerage firm of Kluge & Co.) were biding their time in the wake of the FCC edict on split programming, and searching for potentially successful formats for their FM stations. They realized that Donahue was on to something, and in October 1967, Metromedia changed the format of WNEW, their New York FM, to progressive rock. When Donahue and his staff struck at KMPX over starvation wages and "the whole long hair riff," Metromedia invited them to KSAN, their FM station in San Francisco, which until then had run a tepid "lively arts" mixture of jazz and classical music.

From the original stations in San Francisco, Los Angeles and New York, FM rock spread to the Northeast and the Midwest, and into the colleges. By 1969, independent FM rockers had sprung up in Boston, St. Louis and Sacramento, and Metromedia had reprogrammed its affiliates in Cleveland, Philadelphia and Los Angeles, in addition to those already in San Francisco and New York.

During the initial flowering of FM rock, the stations were highly responsive to new music and to the burgeoning youth communities that formed the bulk of their audiences. The stations experimented musically, embracing, as Donahue put it, "the best of today's rock 'n' roll, folk, traditional and city blues, raga, electronic music and some jazz and classical selections." Black rhythm and blues music, or soul, was integrated with the exploding white music in a mixture unheard since the early days of rock 'n' roll radio in the '50s.

FM disc jockeys were hardly the "happy sounding cretins poured from a bottle every three hours" that Donahue had railed against on Top 40 AM stations. DJs on FM laughed, gave long introductions about musical origins of the songs and talked to their audience as friends. Unlike AM disc jockeys, who were told what to play by the music director (in part because music directors were worried about charges of payola and thus careful to insure a uniform station sound), DJs on the new progressive FM stations had near total freedom to play whatever they wanted.

Some progressive FM station owners were slower than others to fathom the popularity of "free form." At the Boston FM, WBCN, for instance, co-owner Ray Riepen was angered when fledgling DJ John Brodey played Blind Faith's "Do What You Like." In the middle of the song Riepen called Brodey on the studio hot line. "Hey, hotdog!" he boomed. "Nobody wants to listen to a drum solo on a Sunday afternoon!" Brodey was cowed, but the disc jockey who followed him, Charles Laquidara, was incensed. Laquidara, who was tripping on mescaline at the time, retold the incident over the air in dramatic detail, then put on one of his favorite records, the long version of Ginger Baker's drum solo "Toad." He followed the cut with other drum songs: Aynsley Dunbar's "Mutiny" and some selections from Buddy Rich. WBCN listeners were ecstatic and jammed the switchboard for hours afterward with congratulatory messages. Free-form programming stayed.

To handle audience response, FM stations established switchboards that provided listeners with rides, addresses of places to spend the night and news of concerts and demonstrations. San Francisco's KSAN was "information central," Donahue remembered in 1973. "The station was just where people would call when they were in trouble. The classic was at KMPX where a kid called one day who'd been busted in Sacramento for grass. They allotted him one phone call, so he called us, “cause we were the only friend he had. You had a lot of that." Many FMs built radical news departments that did not simply “rip and read”the wire service releases as AM did, but gathered their own news from a variety of sources.

Internally, FM stations ran more democratically than AM outlets. Disc jockeys met in music meetings to decide on new records; newscasters did not need approval by station managers and network officials to air controversial material. A few FMs, like KZAP in Sacramento and KMPX in San Francisco, abolished the program director position, distanced the staff from the general manager, and acted as a collective of DJs a nd newspeople. Even commercially, the original stations, especially the non-chain independents, were often responsive to the anti-materialism of the youth communities. Many progressive FMs, like WBCN, refused to advertise cigarettes, or the products of particularly conspicuous war-making corporations. In the aftermath of the burning of the Santa Barbara Bank of America branch, KZAP, among others, turned down Bank of America ads.

Limitations were inherent in "revolutionary rock radio" from the beginning, however. The audience may have consisted of high school and college dropouts with non-traditional lifestyles, but it was largely white. And the music itself, full of "Midnight Ramblers" and "back door men," was hardly sensitive to the burgeoning women's movement. FMs, as a whole, took years to hire women DJs. Allegedly anti-materialistic ad policies were still commercial. They simply favored record companies and small, hip businesses, such as vegetarian restaurants, over national corporations, oil companies and banks. Such policies were also untested in these early years, because with small and isolated audiences, most FM's had few national advertisers knocking on their doors.

SLEEPING WITH THE DEVIL

The first large advertisers to recognize the commercial value of FM rock radio were the record companies. For the most part the record companies, denied access to AM with their newer rock acts, were searching for ways to promote their Dylans, Zappas, Butterfields and Garcias. The commitment of the DJs to their music combined with the audio superiority of FM made FM the ideal vehicle for sophisticated rock music. The record industry was becoming a very big business during the late '60s and early '70s. In 1956, when Elvis Presley began to record for RCA, record sales had reached only $377 million anually. With the Beatles, who represented the dawning of the golden era, 1965 sales climbed to $862 million. But by 1970—between the car stereo market and the explosion of new rock—sales of recorded music approached $2 billion a year. The record business had millions of advertising dollars to pump into FM radio. FM rock became the showcase, introducing Jimi Hendrix and Frank Zappa to every American backwater town with two bands on its radios. Today, even with the addition of huge, new national advertisers, the record companies, along with stereo component manufacturers and concert promoters, are still the largest advertisers in many FM cities. In San Francisco, for example, record and hi-fi equipment companies take up 40 per cent of the advertising on KSAN, still the most popular FM station in town. As FM rockers demonstrated their hold on the high-spending 18- to 34- year-old market, other consumer industries joined the music advertisers. Airlines, soft-drink companies, breweries, cosmetics manufacturers, auto makers and even Army recruiting centers began to replace small community businesses. Local businesses were, for the most part, shut out by rising prices. The price for a 60-second, prime-time slot on a Los Angeles or San Francisco progressive FM station shot from $10 in 1967 to $76 this year.

Staffers at some stations protested the change to high-powered national ads, but were often overruled by salespeople and station management. When a newscaster complained that KSAN should refuse an ad for the Standard Oil additive F-310 because the independent tests showed it did nothing to improve auto performance, Tom Donahue, then the station manager, laid out the basic truth: "Radical community stations are supported by advertisers with money. If you get in bed with the devil, you better be prepared to fuck."

Joe Lerer, the "Ace" of KSAN weather news, recollects some of his experiences in FM radio in the 1970s on this audio recording from 2009... his part is focused on minute 13:00-20:00, but the whole program is interesting.

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/HearingTheCityEvolutionOfRadio" width="410" height="40" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

During the shift to national advertisers, stations helped to co-opt themselves. National advertisers at first sent over offensive-sounding commercials that had been taped for Top 40 or even Easy Listening stations. FM stations, like KSAN and WNEW, rewrote the ads to jive them with rock music and laid-back DJ patter. "Why do you advertise McDonald's hamburgers?" asked a New York interviewer. "Well, doesn't everybody eat hamburgers?" replied Scott Muni, WNEW-FM's program director. "It's the sound, the sound that creates the problems." The upbeat ads were liked by DJs because they sounded good and by national advertisers because they sold products better. Thus FM rock was integrated more securely into the corporate economy.

By 1974 a major FM station on the West Coast was grossing close to $2 million annually. In the huge New York market, revenues were topping $4 million. Five years before, most FMs were barely breaking even. Overall, FM ad revenues climbed from $40 million in 1967 to about $260 million in 1975. There are more than 2,900 commercial FM stations in the United States, but the bulk of revenues is concentrated in the 40 largest FMs, centered in City markets: the ABC and Metromedia chains dominate, along with a few important independents, such as Boston 's WBCN. FM followed a familiar media dynamic. Its music brought it a mass audience. A mass audience increased its ratings. Higher ratings brought bigger ad accounts and more expensive ads. High-priced ads meant vastly increased revenues—FM rock had suddenly become big business, underground no longer. As a large business, each FM rock station began to hire more salespeople, invest in better equipment, fund expanded news staffs and raise DJs' salaries. In some cases, increased revenues led to plusher quarters; WBCN, for instance, moved to the penthouse suite of the 52-story Prudential Tower, Boston's most prestigious office building.

THE DEATH OF FREE FORM

Mass audiences and higher ratings did not mean greater freedom for DJs to play more of the music they wanted. Ironically, success put limitations on both DJs and music. With new high overheads, the program directors, station managers and chain executives were running scared; to support the stations at the level they had reached, the ratings had to be maintained at all costs.

"Now we have to eliminate sludge," explains Norm Winer, the program director at Boston 's WBCN, "the self-indulgence and excess that is one of the hallmarks of this type of radio. We're not saying 'Compromise,' but we are saying, 'Don't waste anytime; don't take any chances; play a record you know is good.'" Of course playing a record that has proven to be "good" means, as in AM, playing a record that sells.

WBCN do not play All Hits All the Time, but three years ago the station introduced what is called an "emphasis section." The emphasis section consists of high-selling records, determined by trade magazine national charts and surveys of 20 Boston record stores: records being given heavy air-play at other progressive FMs across the country; records by artists appearing in Boston; and new records by superstars. In all, the section comprises 75-80 albums. According to Winer a DJ does not have to play emphasis records if he or she doesn't want to. But DJs are encouraged to, and logs of their shows are checked at intervals by station managers.

The music has been tightened even at San Francisco's KSAN, long regarded by programmers as the most free form of the big commercial stations. At KSAN the emphasis section is large and the pressure to play from it subtle. Bu t management constantly reminds DJs to cater to young, white rock fans, who make up the bulk of the station's audience. The emphasis section, known as the "red-dot file," consists of several hundred "meat and potatoes records," as station manager Jerry Graham describes it. DJs are not actively encouraged to play from the red-dot file, but the word gets to those who consistently stray too far from playing rock selections.

"They didn't make you do anything," recalled Dusty Street, a KSAN DJ who played mostly rhythm & blues and soul. "But Donahue wanted more rock. He was right because he wanted a radio station that was successful."Street switched her daily show to weekends to avoid demands from young rock fans that she play less soul and, according to her, "more Iron Butterfly." Then she left the station altogether, refusing to compromise with management by cutting back on black music.

TOP 40 FMs MUSCLE IN

A new fear now is causing programmers at FM rock stations to regulate the music they play: Top 40 FMs. Top 40 FMs play single hits with a liberal smattering of album cuts. They tend to suck away younger listeners, those 18 and 19, from the progressive stations just down the dial.

After abandoning its syrupy love-song format in 1970, ABC experimented with a free-form approach but jettisoned it when the network found that "too many people were getting carried away with freedom." ABC was beset with DJs "ignoring regulations, uttering obscenities over the air and talking about marijuana, cocaine and heroin. I was spending all day with the legal department trying to bail out one station or another," remembers Shaw. In search of marketable "taste" and control over music and news programming that would not embarrass parent ABC, Inc. in Washington, ABC radio imposed a strict, blander format in 1971.

The new format mixes 15 to 20 hit singles each week with some 20 to 30 albums from which two to four cuts have been chosen. Each single is repeated every five hours. To a large degree, the records are selected centrally in the New York office, with input from the local stations to cover regional differences. ABC follows this format on its stations in New York, Los Angeles, Chicago and Detroit. Significantly, the ABC formula is succeeding against progressive FM stations in some cities, particularly New York and Los Angeles, where Shaw claims ABC is beating Metromedia's WNEW and KMET.

SOFTENING THE NEWS

Metromedia has been more patient than ABC. It sank several million dollars into FM rock back in 1968, waiting, in some cities like San Francisco, until 1972 to turn a profit. By granting relative autonomy to individual stations, Metromedia gained a reputation for hip capitalist enlightenment. Tom Donahue said last year that Metromedia "wants us to keep our nose clean and make money. Not necessarily in that order." The company has stuck with an approximation of the original free-form music programming. But like ABC it has fired outspoken newscasters who overstepped the bounds of what might be called its "free-form corporate format."

At KSAN, Metromedia fired newscasters regularly during the turbulent early '70s. First to go was Roland Young, a black DJ and newscaster who read over the air a telegram defending Black Panther Chief of Staff David Hilliard. Hilliard had angrily told a "peace and love" crowd at the San Francisco Moratorium that "We will kill President Nixon. We will kill any mother-fucker that stands in the way of our freedom." The telegram urged listeners to duplicate Hilliard's message in their own letters to the White House, so that Hilliard could not be singled out. Young was quickly fired by the station manager. "Roland Young was released from KSAN for a number of reasons, and that was one," recalled George Duncan, president of Metromedia Radio. You don't incite to riot on a radio station. It's against the law."

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/ScoopsLastNewsShowSideB" width="500" height="30" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Side B of an album-version of Scoop's Last News Show

Next to be "released" was Scoop Nisker. Nisker had become famous in the Bay Area for his news collages that wove music into the news. The technique, hardly sensational now, was seen as highly provocative in the early '70s. In the aftermath of a demonstration in Berkeley, which heavily trashed downtown stores, Nisker's collages were blamed by the Berkeley police chief for inciting rioters. KSAN, explained the chief, had become a bulletin board for demonstrators. Nisker was told that his collages had to go, although he was given the option of staying if he agreed to read the news straight. He left. Nisker was replaced as news director by Larry Bensky, now station manager of the non-commercial Pacifica station KPFA-FM. Bensky was fired from KSAN five minutes after he offended Jeans West, a $5,000-a-month advertiser. On his newscast Bensky interviewed two employees of Jeans West, who alleged that the company forced its workers to take regular lie-detector tests in which they were asked whether they had ever smoked marijuana or whether they stole; Metromedia is willing to employ radicals like Bensky or right-wingers like George Putnam, who worked a Los Angeles talk show, so long as ratings stay high and advertisers are happy. Corporate owners can tolerate radical newscasts as long as they, in Duncan's words, "strive to be objective," do not become too rigorously analytical and above all do not call on listeners to do anything.

Larry Bensky during his KSAN days.

If somehow local newscasters go much too far and draw fire from the FCC, high-priced corporate lawyers are put into action. Metromedia has played it doubly safe in recent years by hiring Herb Klein, the former director of communications in the Nixon White House, as its vice president for corporate relations. Since Metromedia is a diversified conglomerate with sales of more than $250 million a year through radio, television and entertainment advertising, it must, like ABC, do little to jeopardize the parent corporation's relations with regulatory agencies such as the FCC.

In recent years corporate owners have been just as quick to silence anti-commercial DJs as they have been to shut up newscasters. A year ago, for example, the Concert Network Corporation, which owns WBCN in Boston, suspended DJ Charles Laquidara, who got into trouble again for commenting, after an ad for Honeywell Pentax cameras, that the parent firm was a major war-making corporation that had helped "kill all those Cambodian babies."

Now very few DJs would risk their jobs by attacking advertisers. Laquidara is an exception. At this point few DJs would even think to criticize sponsors and corporate owners. But outright censorship and periodic firings over controversies involving advertisers have played only a minor part in softening the voices of progressive FM DJs. Their integration into the hipoisie of the music and broadcasting industries has quelled their dissent considerably. Being a disc jockey at an FM rock station is a very pleasant occupation. Whereas seven years ago disc jockeys and newscasters at KSAN made $100 a week, now they earn at least $400. At WNEW in New York, or at its ABC counterpart, WPLJ, the average salary is about $600 a week.

High salaries do not automatically weaken DJs' commitments to their audience, but the money they make puts them in a different milieu from the students or factory workers who listen to the station. With the immense growth of the music industry, DJs often identify more with silver-spoon-carrying producers, concert promoters, promo people and rock critics than they do with any former counter-cultural community. "There's too much money and status and dope for them to change and fight now," says Dinah Vaprin, a former announcer at WBCN. "The only time an FM staff would hold a struggle meeting now," echoes Larry Bensky, "is if there was a pound of cocaine that needed dividing." Not all DJs have been seduced, and not all newscasters silenced. Like their counterparts at the alternative news weeklies, many principled DJs were disillusioned by the Left cultural drift in the mid '70s. Radical journalists in print or broadcasting keep their politics more easily when they are linked to on-going movements. There have been signs at KSAN, for example, that a few newscasters are fighting again for stronger-toned news analysis.

Could "free-form revolutionary radio" ever have been viable? Probably not. Despite the motives of radical, community-oriented disc jockeys and newscasters, FM radio was from the beginning a corporate venture. Within months after Tom Donahue started KMPX, the Metromedia conglomerate recognized the potential commerciality of FM rock. Within a year-and-a-half, giant ABC had stepped in. The media corporations were willing to allow radical community responsiveness so long as it built a mass audience; they balked when DJs and newscasters chose to define responsiveness on the basis of politics rather than commerciality.

"Our concept at ABC," said Allen Shaw, "was to take the positive side of the cultural revolution rather than the revolutionary side, to create a radio format that would express those values rather than revolutionary values." Free-form FM could have survived, perhaps, but only if station owners, DJs and newscasters had been willing to limit their own success.

The authors have just completed a book, Rock 'n' Roll Is Here to Pay: The History and Politics of the Music Industry [published by Burnham Inc. Publishers in 1977].