Cecilia Chiang: Chef as Culture Shaper: Difference between revisions

m Protected "Cecilia Chiang: Chef as Culture Shaper" ([Edit=Allow only administrators] (indefinite) [Move=Allow only administrators] (indefinite)) |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' | '''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' | ||

''by Brandon Whiteley'' | ''by Brandon Whiteley, 2017'' | ||

[[Image:Whiteleybrandonpatrick The-Mandarin Chiang-2015.jpg]] | [[Image:Whiteleybrandonpatrick The-Mandarin Chiang-2015.jpg]] | ||

Revision as of 17:20, 9 November 2020

Historical Essay

by Brandon Whiteley, 2017

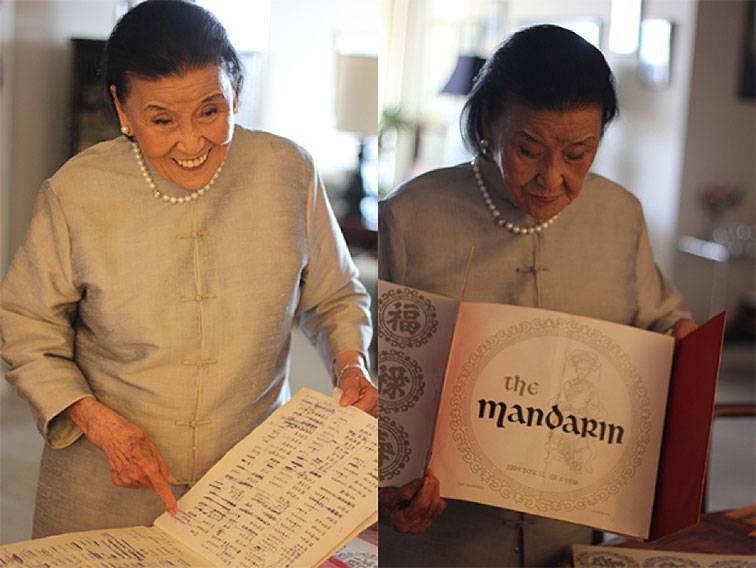

Cecilia Chiang, who turned 95 in 2015, with her original menu

| Cecilia Chiang is perhaps the most famous Chinese American chef of her age. Since her arrival to San Francisco over fifty years ago, Chiang has used her authentic dishes to redefine Chinese cuisine in America, elevating it from cheap, greasy chop suey to refined balance flavors. Along the way, she challenged Chinese stereotypes to reveal a rich and complex Chinese culture that was far more accessible than many Americans had believed. |

When looking for gourmet Chinese food in San Francisco, you have options. There is longtime classic Yank Sing, whose dim sum earned it a spot on Michael Bauer’s list of 100 best restaurants in the city. (1) There is also the new upstart Mr. Jiu’s, which garnered a coveted Michelin star in 2016 by updating Chinese flavors with California ingredients. Indeed, gourmet Chinese food is neither radical nor difficult to come by in today’s San Francisco, but in 1961, it was a different story. That year, a middle-aged Beijing restaurateur named Cecilia Chiang opened an upscale restaurant serving authentic dishes from Northern China. The Mandarin, as it was named, brought hundreds of authentic dishes to San Francisco, and in the process, reshaped the landscape of Chinese cuisine in the United States.

Origins of Chinese-American Cuisine

The history of Chinese food in America has modest roots that trace back to San Francisco’s Gold Rush. As thousands of Chinese men came to the city in search of gold, they brought with them rice, dried meats, pickled vegetables, and sauces meant to sustain them on their journey. (2) Arriving in the gold camps, they continued to eat these foods, with some Chinese immigrants opening grocery shops to feed their fellow miners. However, the camps were segregated by race, so despite the large number of Chinese immigrants to California during the 1850’s, contact between American and Chinese communities in gold country was extremely limited. (3) The Chinese community in San Francisco was similarly isolated, but it was here where the first Chinese restaurants opened in the United States. These initial establishments opened between Kearny and Stockton Streets and Sacramento and Jackson Streets, drawing both curiosity and suspicion from many westerners for their strange ingredients and aromas. (4) Anti-Chinese racism prevalent during this period compounded this skepticism, and Chinese food was often derided as unsanitary and largely inedible. Those who did eat there did so for the novelty.

However, historian Joseph R. Conlin noted that because they “offered all you can eat meals at a fixed price,” these restaurants “attracted western miners when their funds were low.” (5) They were a place of last resort for these miners, who inadvertently became the first western community to experience Chinese cuisine. Because of their unfussy clientele, these first Chinese restaurants created authentic, if inexpensive, Chinese food, with only minor adaptations due to the lack of availability of Chinese ingredients. However, the restaurants’ servers and cooks also “marketed Chinese ethnicity” to their hungry customers, branding Chinese food as cheap, convenient, and unrefined. (6) This stereotype that would persist for next hundred years.

Widespread American fascination with Chinese food began much later. In 1896, the first Chinese restaurants outside of Chinatown began to open in San Francisco and New York. (7) Known as chop sueys, these restaurants served Westerners their namesake dish made of stir-fried meat, eggs, vegetables, and noodles. The dish was decidedly American, but nonetheless chop suey—and its cousin chow mein—was seen as exotic and became wildly popular in the initial decades among Bohemians who saw the restaurants as late-night dens of “loose morals, opium” and “racial mixing.” (8) Eventually, the restaurants grew to be popular with less cosmopolitan Westerners, and chop suey found its way into cookbooks, supermarket freezers, and, even diner menus. (9) Meanwhile, menus at “Chinese” restaurants filled up with doctored versions of Chinese dishes, and the practice proliferated to the point that chop suey and chow mein became synonymous with Chinese food. The restaurants remained popular into the 1960’s, even after it was revealed that chop suey literally translated as “leftovers” in Cantonese. (10) For Americans, the neighborhood restaurants with cheap food, red and gold décor, and fortune cookies—none of which resembled restaurants in China—reinforced the view of Chinese culture as cheap, unsophisticated, and decidedly other.

The Mandarin

When Cecilia Chiang first came to the United States in 1959, she didn’t have plans to change that view. Indeed, Chiang came to San Francisco from her home in Tokyo the previous year simply to pay a visit to her elder sister. (11) While in town, she ran into two old friends who were looking to secure a deposit to open a restaurant, and Chiang agreed to help them out. She placed the $10,000 deposit, but her friends scrapped their plans at the last minute, leaving Chiang with the lease. (12) Not wanting her deposit to go to waste, Chiang decided to open her own restaurant instead.

Chiang came from a well-to-do family in Beijing in the 1920’s, but was forced to flee from invading Japanese forces in WWII, and later communist forces during the revolution. (13) After spending time in Shanghai, she moved with her husband to Tokyo, where, unable to assimilate to Japanese food, she opened a Chinese restaurant called Forbidden City in 1951. (14) The restaurant was popular among Chinese expats looking for a taste of home. Chiang maintained a managerial position in the enterprise, never cooking in the kitchen, but she did learn the workings of the restaurant industry through her time in Tokyo.

Ten years later and five thousand miles away, Chiang hoped to recreate her success with Forbidden City at the Mandarin. Unfortunately, she faced an uphill battle. Her success at Forbidden City was due in large part to a northern Chinese client base yearning for a taste of home; in San Francisco, most Chinese people were from southern regions like Guangzhou and Hong Kong and had no memories of Chiang’s northern dishes. (15) Because she was a foreign-born woman, she could not obtain a liquor license for her restaurant. (16) Furthermore, Chiang spoke Mandarin, not Cantonese, and found it difficult to convince vendors to supply her with Chinese ingredients, which were in high demand at the time due to quotas on Taiwanese imports. (17) Perhaps most difficult to overcome was the Mandarin’s location: at 2209 Polk Street, the restaurant was well outside of Chinatown. (18)

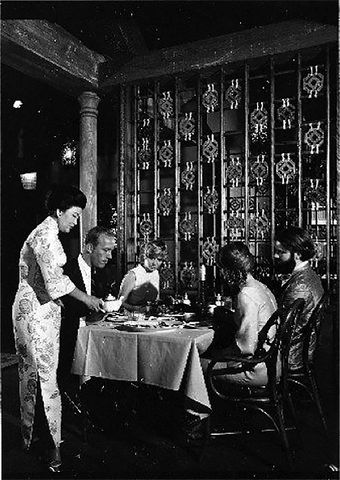

The Mandarin in 1970.

All these challenges made the initial years of the Mandarin difficult. The first eighteen months saw few customers and large losses, despite a 300-item menu of traditional Chinese dishes. (19) Chiang received multiple suggestions from successful Chinese-American restaurateur Johnny Kan to shorten and Americanize her menu as he had done for his famous Chinatown restaurant, Kan’s. (20) Nevertheless, she persisted, and in 1963, he determination paid off. San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen dined at the Mandarin after a friend’s suggestion and promptly certified the “hole-in-the-wall” on Polk St. as “the best Chinese food east of the Pacific.” (21) Chiang’s northern Chinese style was altogether new to most Americans, but with Caen’s endorsement, they were willing to take the risk. Suddenly, the Mandarin became the hottest restaurant in the city, booking hundreds of reservations in a matter of days. (22)

Chiang handled the rapid expansion expertly, increasing the output of her kitchen without sacrificing quality or hospitality. She continued to serve authentic dishes, often created from her childhood memories, without doctoring them to suit American palates. Some dishes, such as sea cucumber and tofu, were deemed too adventurous for Western clients and were placed only on the Chinese menu, but even her English menu included then-unheard-of dishes like pot stickers (Chiao-Tzu), beggar’s chicken, and Mongolian lamb. (23)

Soon, the Polk Street location grew too small for Chiang’s booming business, and in 1968, the Mandarin moved to the Woolen Mill in Ghirardelli Square. To inaugurate the new space, Chiang hosted an opening banquet featuring her signature dishes. The tickets cost $250 a piece, the highest sum ever charged by a Chinese restaurant in America. (24) Despite the astronomical price, Americans were willing to pay for authentic, high quality Chinese food, and the 300 tickets completely sold out. (25) Chronicle columnist Michael Bauer put it plainly, noting that “before the Mandarin, most of us were used to eating Chinese food surrounded by Formica and Linoleum. Chiang upgraded that significantly, creating a restaurant that reflected her impeccable taste” with service “as you’d find in the most expensive French restaurants.” (26) After the Mandarin, Chinese cuisine was no longer just chop suey and cheap eats.

Chinese Food as Culture

The Mandarin was by no means the first successful Chinese restaurant in America or even San Francisco. Kan’s in Chinatown had been successful since its opening 1953, and Emily Kwoh’s Mandarin House in New York debuted many of the Mandarin’s signature dishes three years prior to Chiang, in 1958. (27) However, these restaurants either Americanized their menus or focused solely on the quality of the food. At the Mandarin, Chiang not only managed to serve excellent, authentic Chinese dishes, but also more purposefully exposed her diners to Chinese culture. At the Mandarin, the décor was based on Chiang’s childhood home in Beijing, and the menu explained Chinese dining customs. (28)

In 1972, Chiang began offering cooking classes at the Mandarin, encouraging her students to bring authentic Chinese cuisine into their homes. Her students included noted individuals like James Beard, Chuck Williams, and Julia Child. (29) Also in attendance was Alice Waters, who attended Chiang’s class just two years after opening Chez Panisse, and the pair became fast friends. (30) In 1983 the duo, along with fellow chef Marion Cunningham, traveled to China, where Chiang exposed them to regional Chinese cuisines. Waters credits Chiang with infusing California menus with Asian influences, a key aspect of modern California cuisine. (31)

Chiang’s ability to intertwine Chinese food and culture becomes even more present in her cookbook and memoir, The Mandarin Way, published in 1973. Each chapter begins with a vignette about her life in China before introducing some of her favorite childhood recipes. (32) The memoirs describe her sheltered childhood in Beijing before detailing her harrowing journeys to escape from Japanese soldiers and communist forces. They offer a sincere and humanizing view into Chinese culture and tradition, while the recipes included serve to support that notion. Unlike Johnny Kan’s cookbook, Eight Immortal Flavors, which features dishes like “Pineapple Chicken” with ketchup, Tabasco, and Worcestershire sauce, the dishes Chiang selects are memories from her time in China. (33, 34) She couples her story about the Autumn festival with recipes on Banquet cooking while pairing her arduous escape from occupied Peking with recipes on how to use Chinese leftovers. Just like its namesake restaurant, The Mandarin Way used Chinese food as a vehicle to teach Americans about Chinese culture.

Cecilia Chiang sold the Mandarin in 1991, and the restaurant finally closed in 2006 after 45 years of service. (35) Since the closing of the restaurant, Cecilia Chiang has remained active in San Francisco’s food scene. She remains good friends with Alice Waters, serving up a special 40th anniversary dinner at Chez Panisse in 2011. (36) She hosts lunar new year’s parties, where, at 97 years of age, she reprises her favorite dishes for friends and family. (37) Chiang also helps her son, Philip, design new dishes for P.F. Chang’s, the restaurant chain he cofounded in 1993. (38) She keeps an eye on the future of Chinese cuisine as well, advising new and upcoming chefs like Andy Tsai and Li Jun Han, who are continuing her work by serving up authentic, high quality dishes.

During its tenure, the Mandarin helped to usher in a new American understanding of Chinese food and culture. Thanks in part to Cecilia Chiang, the cheap, caricatured chop suey restaurants of the first half of the 20th century gave way to a type of restaurant that reflected China’s rich and complex history. In doing so, Chiang encouraged her patrons to better understand Chinese culture, breaking down the ethnic barriers between Chinese-Americans and Westerners that had lasted for over 100 years.

Works Cited

Bauer, Michael. "At the Mandarin, Cecilia Chiang Changed Chinese Food." Inside Scoop SF. San Francisco Chronicle, 12 Feb. 2012. Web. 05 Mar. 2017.

Bauer, Michael. "Top 100 Bay Area Restaurants 2016." San Francisco Chronicle. N.p., 27 Apr. 2016. Web. 16 Mar. 2017.

Chang, Momo. "Q&A with Cecilia Chiang of The Mandarin Restaurant." PBS. Public Broadcasting Service, 09 Apr. 2015. Web. 05 Mar. 2017.

Chiang, Cecilia Sun Yun., and Allan Carr. The Mandarin Way. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Compay, 1974. Print.

Coe, Andrew. Chop Suey: A Cultural History of Chinese Food in the United States. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2009. Print.

Freedman, Paul. Ten Restaurants That Changed America. New York: Liveright, 2016. Print.

Kan, Johnny, and Charles L. Leong. Eight Immortal Flavors. San Francisco: California Living, 1980. Print.

Kane, Peter Lawrence. "Cecilia Chiang Is 96 and Goes Out More Than I Do." SF Weekly. N.p., 08 Aug. 2016. Web. 16 Mar. 2017.

Liu, Haiming. From Canton Restaurant to Panda Express: A History of Chinese Food in the United States. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP, 2015. Print.

Rude, Emelyn. "Chinese Food in America: A Very Brief History." Time. Time, 8 Feb. 2016. Web. 05 Mar. 2017.

Soul of a Banquet. Dir. Wayne Wang. Perf. Cecilia Chiang. PBS Food, 2015. Web.

Wong, Bernard P. Ethnicity and Entrepreneurship: The New Chinese Immigrants in the San Francisco Bay Area. Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 1998. Prentice Hall. Web.