Carpenters' Strike April 1926: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' | '''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' | ||

''based on | ''based on ["The 1926 San Francisco Carpenters' Strike," Masters Thesis, SFSU, Eric Levy, 1986.]'' | ||

[[Image:labor1$picket-ordinance-1916.jpg]] | [[Image:labor1$picket-ordinance-1916.jpg]] | ||

Revision as of 16:39, 12 July 2016

Historical Essay

based on ["The 1926 San Francisco Carpenters' Strike," Masters Thesis, SFSU, Eric Levy, 1986.]

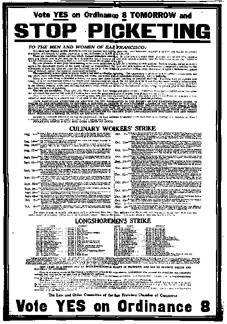

The Chamber of Commerce passed a municipal ordinance in 1916 banning picketing, which criminalized the carpenters during their 1926 strike.

This strike came in the midst of the Industrial Association's American Plan open-shop reign over San Francisco. The carpenters could not picket legally, and the legitimacy of their union was not recognized or protected by the government. Violent confrontations with non-union carpenters and vandalism of non-union construction projects became a daily occurrence. The strikers were easily marginalized by the pro-employer Chronicle and Examiner. On April 27, the Board of Supervisors ordered the police to stop providing protection for the non-union American plan job sites. The Industrial Association petitioned for a new hearing, but were refused, whereupon they threatened to revive the well established tradition of vigilantism in the service of property when their chief spokesman Albert Boynton said they would take any measures necessary to "reinforce the law and stamp out this wave of violence and crime that is threatening the peace, progress, and prosperity of our city." The Supervisors' attempt to mediate failed due to the Industrial Association's control and intransigence in refusing to recognize any unions or collective bargaining agreements.

Mayor James Rolph grew frustrated and accused the Industrial Association of "jeopardizing public interest for private gain... it is time for a showdown on this matter. The Industrial Association is not going to stop public building in this city. If the Association thinks that it is above the public good, I am going to find out about it." But after the Industrial Association used its might to squeeze building materials and credit to union shops and public works, Rolph conceded, "we want materials, not litigation." By October, Rolph had fully joined the efforts of the Industrial Association to defeat the carpenters, and declared he was "determined to use the police force to stamp out this brutality." On October 21, several non-union workers were severely beaten while leaving an American Plan job site. The next day one of them died. This incident, played up in the papers, firmly turned public opinion against the strike. In January 1927, the Carpenters agreed to accept the "Impartial Wage Board" raise to $9/hour, and to work under "present conditions," i.e. the open shop. The Industrial Association was just too rich and influential. Finally, they went on publishing articles about the strike and its many violent episodes for several years to come, grist for their anti-union mill. But the Carpenters had fought a spirited guerrilla war for more than six months, stopped a lot of work and done a lot of damage. Its defeat led to demise of Building Trades Council power.

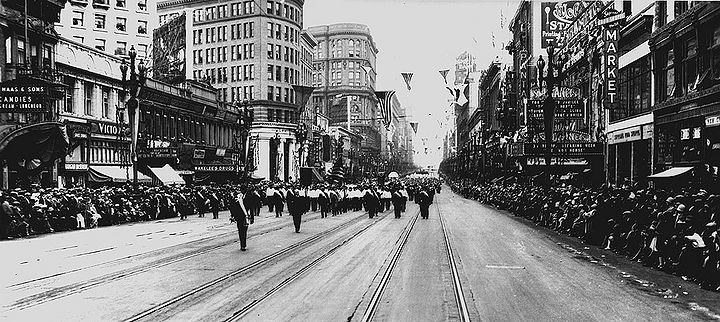

Labor Day Parade, September 7, 1925, seen here on Market Street east of 6th Street.

Photo: C. R. collection