Strawberry Creek: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m Protected "Strawberry Creek" ([edit=sysop] (indefinite) [move=sysop] (indefinite)) |

(No difference)

| |

Latest revision as of 12:30, 26 August 2015

Historical Essay

by Sruthi Davuluri

Strawberry Creek, 2015.

Photo: Sruthi Davuluri

| Strawberry Creek runs down the western slopes of the Pacific Coast Mountain Range through the city of Berkeley into the San Francisco Bay. In some stretches along is route to the Bay, it is a beautiful and ecologically vibrant feature of the East Bay watershed. Although much of it now lays underground, its history should not be forgotten. This essay explores the political, cultural, and geological history of Strawberry Creek as an entry point in many related topics including the Shellmounds of the Ohlone Tribe, the construction of Memorial Stadium, and the development of the Urban Creeks Council. |

One of the first things people notice when strolling through the UC Berkeley campus is the sound of trickling water flowing through Strawberry Creek. A variety of trees, which include oaks, redwoods, and some of the tallest eucalyptus trees in California canopy the stream.(1) While many students do homework along the banks of the creek, very few know about its rich political, cultural, and geological history. Prior to the arrival of the Spanish, the Huchiun-Ohlone tribe used to live along Strawberry Creek. They appreciated and utilized the body of water more than the European and Euro-American settlers colonists of the 17th and 18th centuries. The banks of Strawberry Creek were further impacted with the arrival of the University of California Campus. As the attitudes and practices of the people towards the creek changed over time, the geological characteristics morphed alongside them.

The relationship that humans have had with Strawberry Creek begins with the Huchiun-Ohlone Tribe.(2) Prior to colonization, the natives developed a symbiotic relationship with the natural environment around them. The native traditions consisted of taking what one needed and living in harmony with one’s surroundings. The Huchiun-Ohlone Tribe had a spiritual connection with the body of water. They would pray and sing to the water, which would then support the people in return. The Ohlone used the creek as a food source, water source, and for bathing.(3) Up until the late 1700s, the Strawberry Creek had native species including steelhead trout, salmon, and shellfish.(4) Steelhead trout and rainbow trout are the same species and genetically equivalent but the former are anadromous; that is, spawned in freshwater streams, steelhead migrate to the sea. After several years, they return to spawn in the streams of their birth. In contrast, the rainbow trout spend their entire lives in the stream.(5) There is evidence that the Native Americans would regularly eat shellfish provided by Strawberry Creek.(6) While eating shellfish, Ohlones would throw the empty shells into a pile, which eventually formed a shellmound. There is a shellmound at the mouth of Strawberry Creek, where it opens up into the Bay. This shellmound signified a sacred place where the Ohlone would bury their ancestors. Unfortunately, the portion of the shellmound that was above ground was destroyed over the century following colonization, but the land is still commemorated by the Indian People Organizing for Change(IPOC) today.(7) In addition to shellfish and trout, the Ohlone tribes would live off of acorns and seeds that grew on the banks of the Strawberry Creek. The legendary strawberry vines themselves lived along the banks at one point.(8) Since the Huchiun-Ohlone tribe realized how imperative Strawberry Creek was to the survival of its people, they appreciated the creek and did not misuse it. The Ohlone understood that if you took what you needed and nothing more, the creek would support you forever.

When the Spanish began exploring and occupying the region in the late 1700s, they brought with them destructive ecological practices and invasive species. The Spanish would graze many cattle, which were not native to the Bay Area. Not only would the cattle overgraze the lands, and trample over the native grasses, leading to soil disturbance, but the animal waste would also kill native species in the Strawberry Creek. The problem of sedimentation and soil disturbance is not only bad for the aesthetics and color of the creek, but it also prevented insects from laying their eggs under the stones and rocks.(9) These insects are imperative to the balance of the ecosystem. A family-owned dairy farm operated near the Strawberry Canyon. Thus, the agricultural waste led to an excess of nitrogen and silt downstream in Strawberry Creek. The Spanish arrival most likely led to the demise of the native grizzly bear as well.(10) During the time period of the Gold Rush, many discouraged miners settled out in the Bay Area. These settlers saw the land as a source of profit and capital, and did not appreciate its true [non-monetary] value. The settlers continued to disturb the soil with the cattle paths and use the land until the UC Regents came to the Strawberry Creek.

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/GrayBrechinOnBerkeleyAndStrawberryCreek" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Dr. Gray Brechin talks about the founding of both the University and the town of Berkeley along the banks of Strawberry Creek.

Video: Sruthi Davuluri

In 1857, the University of California was searching for a suitable campus to move to from Oakland. The campus officials chose this site because they wanted to use Strawberry Creek as a year-round water supply. The College Water Company was hired, who built reservoirs in the Strawberry Canyon springs out of brick and developed infrastructure to deliver water to the campus. The use of the creek as a water supply and for irrigation begins the irreversible demise of the creek. The College Water Company built additional dams at the turn of the 20th century in order to satisfy the needs of the people. As the city grew, the demand exceeded supply. As a result, a huge water tank was built in the Canyon. Around the 1930’s, the Campus began importing water from the Sierra snowmelt.(11) The main difference between the way that the Ohlone Tribe used the water, when compared to the way the people of the 20th century used the water, is the fact that the settlers and city officials would make drastic changes to the creek in order to get the response they wanted. The Ohlone people would collaborate with the creek in order to fulfill the needs of the people. Instead, the settlers would rather engineer a false system, and disregard the effects it would have on the creek and its surrounding ecosystem. During this time period, the Strawberry Creek was being used for drinking water, irrigation, and sewage. Water would be extracted at unsustainable amounts upstream and the human waste would flow into the creek downstream. The 1900s are known as the “Dark Ages” for urban creeks, like Strawberry Creek, across the country. The place that was once used for fishing and swimming was now treated as an open sewer. People claimed that they knew that were near the UC campus when they could smell the onerous sewage. Additionally, there were negative health consequences associated with the sewage problem. When the wastewater percolates to the groundwater, then it is common for it to be ingested by humans. It is difficult to decontaminate sewage when it hits the water table below ground. The city sanitary sewer system was finally built in the 1890s, which helped mitigate the wastewater issue.

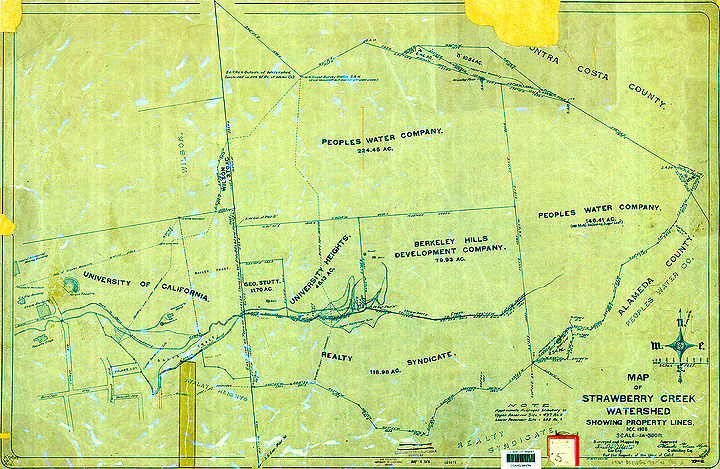

Early map of Strawberry Creek

In addition to human pollution, the flow pattern of the water itself has a large effect on the water quality. The use of impervious surfaces, such as concrete and asphalt, allows the water to flow faster than it would on grass and natural surfaces. The rainwater flows into the creek quicker and in a higher quantity, which puts a burden on the creek. As roads and other impervious surfaces were built, it allowed rain to flow faster towards storm drains, instead of slowly percolating through the soil. Grade control structures, which are meant to control water flow and prevent erosion, were put in place during the late 19th century. For example, a rock check dam is a structure intended to slow down the flowing water and reduce harmful erosion. As the campus grew, many dams and retaining walls were built to protect both the campus and the stream banks. However, these unnatural engineered efforts only led to worse effects of flooding and erosion. During the 19th century, Strawberry Creek suffered from undercutting; when the water levels were high during the winter, the water picks up speed and has more power to erode the banks and the streambed. This stream incision leads to faster flowing waters, which resulted in a positive feedback loop.(12)

Since the water was contaminated and smelled horrendous, the city decided to begin covering it up instead of addressing the water quality. In 1883, the first culvert, or underground tunnel, was built below Oxford Street for transportation reasons. The building of culverts continued through the early 20th century until almost all parts of Strawberry Creek were buried underground with the exception of the section along campus. The engineered structures made detrimental changes to the natural flow of Strawberry Creek.(13) By covering up the creek, fish and other aquatic life is prevented from living in these sections of the stream. The culverts represent the beginning of a transition into a time period where the Strawberry Creek is seen more as a nuisance rather than an amenity or utility. The construction of the original football stadium had drastic consequences on the South Fork in 1923.(14) They ran the water underneath the stadium in a culvert soon to be named “Little Inch.” During the 1930s, the Radiation Lab was built, which later became known as the Lawrence National Lab. Since the location of the lab was so close to the Strawberry Canyon, the construction led to inevitable sedimentation and other construction waste. Additionally, it was common during this time period that lab waste would not be disposed of correctly. Since the regulations were less strict during this time period, some of the radiation waste most likely ended up in the Strawberry Creek. The steelhead trout swam through the streams of the Strawberry Creek until about 1920s, because they could no longer live with the pollutants ruining the balance of the ecosystem.

Restoration

For most of the 20th century, the Strawberry Creek had been filled with sewage, urban runoff, chemicals, and litter. Research conducted by Robert Charbonneau and Sonja Biorn-Hansen revealed that there was a spike of ammonia and microbial contaminants during the half times of the football games. Upon further investigation, it became clear that a broken sewer pipe was leaking into the storm-drains. It was difficult to maintain the infrastructure underneath the stadium because it lies along Hayward Fault.(15) Robert Charbonneau later became the author of the Strawberry Creek Management Plan, which mandates extensive water quality reports of the creek to be conducted regularly.(16) It also provides a systematic protocol of maintaining the water quality, the stream bank, and habitat restoration. From 1990, native fish have been slowly reintroduced into the Strawberry Creek with the hopes of restoring some of the original ecosystem.(17) As more people became interested in the quality of urban creeks, more effort was put into the restoration process.

Strawberry Creek running openly in 2015.

Photo: Sruthi Davuluri

However, the battle is not over, and the creek suffers from pollution issues to this day. In the last decade, the East Bay Municipal Utility District (EBMUD) processed our drinking water with a chemical named chloramine.(18) This chemical is supposed to be beneficial to human health. However, it is detrimental to fish and other organisms living in the creek. Chloramine does not volatilize, or turn into a gas, which makes it more difficult to clean from the creek. The use of chloramine is an interesting case of when public health issues may not align with environmental issues. When this EBMUD water is used for washing cars, or a fire hydrant leak, it inevitably flows into the creek and affects the water quality.

Strawberry Creek Park

“Richard Register, left facing, holds a press conference with Mayor Jeffrey Leiter (center) and others. Landscape architects Gary Mason and Doug Wolfe and community organizers Ann Riley, Carole Schemmerling and David Brower were major instigators of the creek daylighting movement, starting with Strawberry Creek.”(19)

When people pass by the Strawberry Creek, few people appreciate how lucky they are to have such a beautiful amenity along our UC Campus. The creek was culverted at Oxford Street and remained underground until it opened up into the Bay. When a creek runs into a culvert, there is a large loss of habitat, which limits the amount of species living along the creek and the environmental health of the body of water. Strawberry Creek is known as the first creek with a successful daylighting project. To “daylight” a creek means to liberate a creek from a culvert or tunnel and allow the water to flow beneath the sky as it once did.(20) During the late 20th century, many people were passionate about environmental projects and restoring a relationship with nature that once existed. Restoration of waterways was being addressed throughout the nation; especially with the passing of the Clean Water Act in 1972. There was a proposition to build a new park in Berkeley, off of Addison Street. However, the chair of the Parks Commission, Carole Schemmerling refused to build a park with a creek running underground. She worked with the designers, Gary Mason and Ed Wolfe, to design a park with an open creek and a closed creek. When putting these two projects side by side, it became apparent that the project with the open creek would be more cost efficient. Mason and Wolfe designed it in such a way that they could reuse the concrete from the destroyed culvert along the stream banks. The soil was reused in the park, and was placed on a hill which put a barrier between the truck traffic and the area where children would play; thus, creating a safer environment for the community. Therefore, no materials had to be taken away, which made the open creek proposal more cost efficient than keeping the creek underground.

A public hearing was conducted, where the city officials mentioned that they were afraid to open a section of the creek because “people will die.” In response to these words, David Brower stood up and claimed “It is your duty as guardians of public space and the environment to open up this creek.” David Brower himself once played in Strawberry Creek as a child, and it would be a pity if the children today could not enjoy the beauty of the creek. Carole Schemmerling said, “The main reason why we could open up the creek was because enlightened people in the city put a bond measure on the ballot to raise $5 million dollars to put parks in neighborhoods that did not have one.”(21)

Eventually Strawberry Creek Park was established in 1982, which continues to be appreciated and used by children and community members to this day. This was the first successful daylighting project, and it inspired many similar projects throughout the country, and the world. Carole Schemmerling and her associates actually helped people leading a similar project in Korea. The success of the Strawberry Creek project brought Carole Schemmerling in touch with Ann Riley, formerly of the Department of Water Resources, who came together to create the Urban Creeks Council.(22) The mission of this non-profit organization is to restore urban streams and initiate community appreciation. Ann Riley explained that the “vegetated open creek eliminates more inorganic and organic pollution than any treatment plant.” The Strawberry Creek Park is not the only evidence that this project was successful. The work that Schemmerling, Register, Riley, Wolfe, and others put in allowed for the citizens to be more interested and educated in urban streams and the importance of maintaining a certain sense of nature in our urban life. The political impetus of this project spread to more projects of the preservation and restoration of our local environment. Since the Parks Department and other activists who fought for Strawberry Creek Park understood the value of urban streams in our community and for the environment, this project came to fruition and inspired others to work towards the same goal.

The Strawberry Creek Park has an area of 4.5 acres, and the city parks department did not have the funds to employ maintenance for such a large area. The Parks and Recreation Department came up with a creative solution: they created an afterschool program for the local school children to come after school and help maintain the park. Therefore, the Strawberry Creek Park remains clean, and the youth in the community learn from the new amenity. When I visited Strawberry Creek Park myself, an elementary school had a field trip to assess the Strawberry Creek. Many of the students were excited by the creek and were eager to learn more about what they could do to restore it.(23)

Many houses are built over culverted sections of the Strawberry Creek. However, many of those culverts have not received the maintenance or refurbishment that they require. Some of the culverts of West Berkeley have been failing, which has caused damage to private residences, along with public land. This raises an issue about who has the responsibility of fixing these areas and who will provide the compensation.(24) Although some believe that the city is responsible for fixing these culverts that the municipalities built years ago, the homeowners are responsible for the culverts beneath their land, by law.

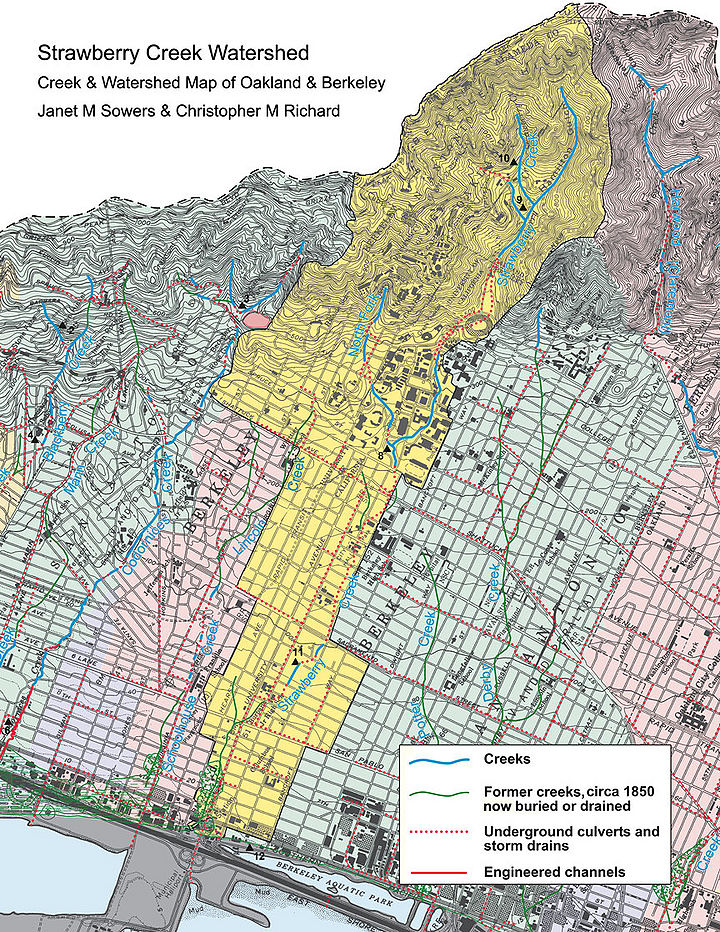

This map, created by Christopher Richard, shows the sections of Strawberry Creek which are above ground and culverted today.

University of California Environment, Health, and Safety (EH&S) Department

Upstream from Strawberry Creek Park, the University of California Environment, Health, and Safety (EH&S) Department continues to do restoration work to this day. A project was recently completed near the confluence of the North Fork with the South Fork. Since the check dams required renovation, they were replaced with natural rock step pools. This new structure was built with more natural materials, and simulated a more natural flow of water to create a natural habitat.(25) It is a challenge to encourage the return of native fish to the creek that was once treated so badly. The presence of anadromous fish is a good indicator of the health of a creek.(26) Although the EH&S would like to implement similar rehabilitative projects around campus, they require more funding. In addition to the UC Campus, a lot of funding comes from the student-funded Green Initiative Fund and UC Berkeley's Capital Renewal Committee.

In contemporary times, the UC campus uses the Strawberry Creek as an outdoor laboratory or classroom. Many classes in the biology, environmental design, environmental science, and other fields of study come outside to conduct lab reports on the quality of the Strawberry Creek or its grade structures. Additionally, many people enjoy reading by its banks or relaxing to the sound of trickling water. The campus is lucky to have such a beautiful stream running through its walkways.

However, the UC Campus is not perfect. In 2011, a pump valve failed in Stanley Hall, which led to 1,700 gallons of diesel fuel to flow into Strawberry Creek and eventually into the Bay. The Berkeley community was aware of the odor from the diesel fuel, and was concerned that the diesel fuel could catch on fire. The Coast Guard came to the Bay to mitigate the problem. However, it is almost impossible to completely eradicate a substance such as diesel fuel from the waterways, and the effect on the aquatic life cannot be undone.(27)

There are current proposals floating around about daylighting a strip of Strawberry Creek on Center Street and Oxford.(28) This proposition has received a variety of responses from the Berkeley community. While some believe that creating a “boardwalk” environment in Downtown Berkeley may create a nice ambience, others argue that the high costs are not worth it.(29) The shopowners most likely want the project to go to completion because it would raise their land value. This proposed project would constrain the stream into a straight portion in between two culverts, and prevent it from naturally meandering, or creating a wavy course. The downtown plaza would prevent the Creek from having native vegetation, which is necessary for a healthy stream.(30) The University had rejected this proposal several times, because the EH&S could use a fraction of the money into improving the sections of Strawberry Creek that are currently flowing along its natural course.

Strawberry Creek, 2015.

Photo: Sruthi Davuluri

Looking back, it seems apparent that the Strawberry Creek was at its prime prior to the European arrival. The habitat seemed to be flourishing when the Ohlone people took care of the creek as the creek provided for them. As civilizations grew and transformed in the Bay Area over time, and the town soon became an urbanized city, the use of the creek changed in the eyes of the locals. When people don’t see the body of water as an important factor in their life, they will not feel compelled to protect it or gain a connection towards it. The creek faced difficult times with pollution and culverts, but it always kept flowing for us. However, the environmental movement brought fresh energy; in order to regain the important connection people have lost with our surrounding nature and truly appreciate aspects of our ambient environment that have been forgotten. If people take notice, and appreciate Strawberry Creek, then we can continue on in our journey of restoration. Since the creek is so close to the UC campus, many classes use it as an outdoor laboratory to study stream flow and ecosystem function. The next time you are in the Bay area, try to stop by the Strawberry Creek and notice the water levels, the types of vegetation surrounding it, and the aquatic life you may find.

Notes

1. "UC Berkeley Strawberry Creek." UC Berkeley Strawberry Creek. N.p., n.d. accessed 26 Apr. 2015.

2. "THE HISTORY." Strawberry Creek Ecological Stabilization Project. N.p., 21 June 2013. accessed 26 Apr. 2015.

3. Rogers, Phila. "Strawberry Creek—The Story of a Stream." Strawberry Creek. Lawrence Hall of Science. accessed 26 Apr. 2015.

4. Schwartz, Susan. "URBAN RIPARIAN RESTORATION: AN OUTDOOR CLASSROOM FOR COLLEGE AND HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS COLLABORATING IN CONSERVATION." (pdf) Madroño 54.3, Special Issue: Ecological Restoration In a Changing World: Case Studies from California (2007): 258-67. Friends of Five Creeks. accessed 26 Apr. 2015.

5. Interview with Christopher Richard by Sruthi Davuluri, April 15, 2015

6. Interview with Grey Brechin by Sruthi Davuluri, March 12, 2015

7. Interview with Corrina Gould by Sean Burns, February 11, 2015

8. Interview with Tim Pine by Sruthi Davuluri, March 11, 2015

9. Interview with Christopher Richard by Sruthi Davuluri, April 15, 2015

10. Interview with Grey Brechin by Sruthi Davuluri, March 12, 2015

11. Robert Charbonneau, Strawberry Creek I (pdf) (n.d), Environment Health & Safety, (accessed 26 Apr 2015), page 4-6

12. Interview with Tim Pine by Sruthi Davuluri, March 11, 2015

13. Interview with Grey Brechin by Sruthi Davuluri, March 12, 2015

14. Robert Charbonneau, Strawberry Creek I op.cit., page 10

15. Robert Charbonneau, Strawberry Creek: A Walking Tour of Campus History (Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley Environment Health & Safety, 1990) 4

16. Robert Charbonneau, Strawberry Creek Management Plan (1987) (pdf), Environment Health & Safety accessed March 29, 2015, page 41

17. 2006, October, Office Of Environment, Health & Safety, University Hall 3Rd Floor, and Ca 947 Berkeley. "Strawberry Creek Water Quality Report." (pdf) University of California, Berkeley Strawberry Creek Water Quality—2006 Status Report (n.d.): n. pag. University of California, Berkeley, Oct. 2006. Web.

18. Interview with Tim Pine by Sruthi Davuluri, March 11, 2015

"Effects on the Environment - Citizens Concerned About Chloramine (CCAC)." Effects on the Environment - Citizens Concerned About Chloramine (CCAC). N.p., n.d. Web. 26 Apr. 2015.

19. "Strawberry Creek Park & Daylighting, Berkeley." Ecocity Builders. N.p., n.d. Web. 26 Apr. 2015.

20. Interview with Tim Pine by Sruthi Davuluri, March 11, 2015

21. Interview with Carole Schemmerling by Sruthi Davuluri, April 25, 2015

22. "Urban Creeks Council | Creeks for People and Other Living Things." Urban Creeks Council. N.p., n.d. 26 Apr. 2015.

23. Interview with Carole Schemmerling by Sruthi Davuluri, April 25, 2015

24. Interview with Christopher Richard by Sruthi Davuluri, April 15, 2015

25. Interview with Tim Pine by Sruthi Davuluri, March 11, 2015

26. Interview with Christopher Richard by Sruthi Davuluri, April 15, 2015

27. "Diesel Fuel Leak Closes UC Berkeley's Stanley Hall." ContraCostaTimes.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 26 Apr. 2015.

"UC Berkeley Oil Spill Elicits Concern over Strawberry Creek Wildlife | The Daily Californian." The Daily Californian. N.p., 12 Dec. 2011. 26 Apr. 2015.

28. Mason, Wolfe. (n.d.): n. pag. (pdf) Wolfe Mason Associates, 1999. Web. 26 Apr. 2015.

"Strawberry Creek Watershed." Strawberry Creek Watershed. N.p., n.d. 26 Apr. 2015.

29. Ecocity Builders, Strawberry Creek at Center Street (Berkeley: Hood Design, 2008), 3

30. Interview with Christopher Richard by Sruthi Davuluri, April 15, 2015